The Complete Carpenter: Ghosts of Mars (2001)

Last month, John Carpenter made his return to the big screen after an eight-year absence. Not as director, but as executive producer and (more importantly) composer for the new Halloween. It was great having him back, the film’s pretty darn good considering this franchise’s track record, and the score is fantastic.

Last month, John Carpenter made his return to the big screen after an eight-year absence. Not as director, but as executive producer and (more importantly) composer for the new Halloween. It was great having him back, the film’s pretty darn good considering this franchise’s track record, and the score is fantastic.

Now I have to come in and get all negative because look what film is next on my (almost finished) John Carpenter career retrospective.

Carpenter has experienced many financial disappointments with his movies, but none was more catastrophic than the reception for Ghosts of Mars in 2001. Costing $28 million to make at Sony’s Screen Gems division (the folks responsible for the Resident Evil and Underworld movies), John Carpenter’s semi-remake of Assault on Precinct 13 set on Mars only grossed $14 during its theatrical run. That’s not the domestic gross — that’s the worldwide gross. In the aftermath of this flop, Carpenter took a near decade-long hiatus from moviemaking and has only directed one film since. (“I was burned out. Absolutely wiped out. I had to stop,” he said in a 2011 interview.)

I’ve examined Ghosts of Mars before. At that time, it was my first viewing since the movie was in theaters. Now that I’ve gotten to grips with analyzing those initial reactions, how does the film hold up? Is it Carpenter’s worst movie, as many people have pegged it?

The Story

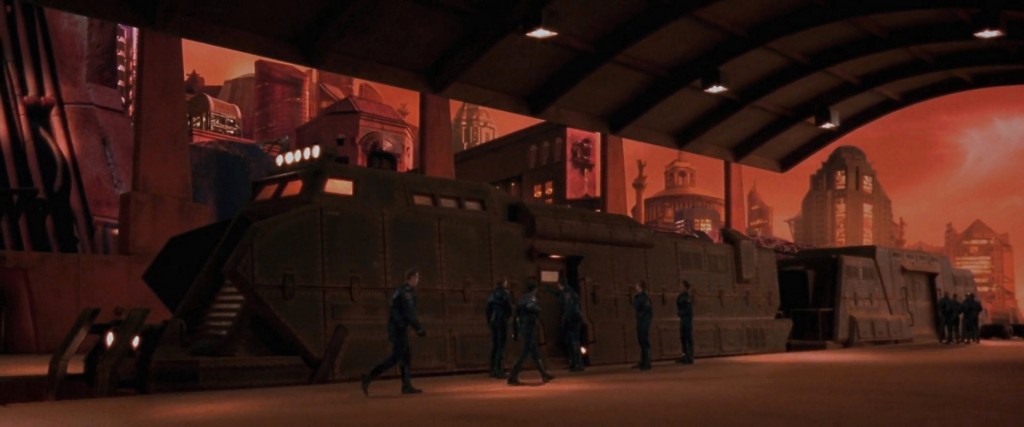

The year: 2176. The place: Mars, now colonized by 640,000 humans under a matriarchal organization, the Matronage. Lt. Melanie Ballard (Natasha Henstridge), an officer in the Martian Police Force, is part of a team sent by train to pick up notorious outlaw James “Desolation” Williams (Ice Cube) from lock-up at the Shining Canyon mining camp. When the MFP arrives at Shining Canyon, they initially find the camp deserted except for a few prisoners locked in cells and numerous mutilated bodies. Soon, they find out what happened: Mars’s long-dormant native population has microscopically turned all the miners at the station into ravening brutes looking to wipe out the human invaders. The MFP teams up with Desolation Williams and the prisoners to survive the onslaught of the Martian host bodies and make it back to the train when it returns.

The Positives

No, this is not my least favorite Carpenter film. Ghosts of Mars has too much potential in its ideas to end up at the bottom of that pyramid. I can imagine a version of it made in the ‘80s that’s one of Carpenter’s best movies. It’s crammed with things Carpenter loves: a thinly disguised Western, a siege story homaging Rio Bravo, anti-authoritarian attitudes, a Hawksian woman protagonist, and an anti-hero wearing a sleeveless black shirt. A complete Carpenter kit — you could build a great model with all the stuff strewn around on the Martian sand.

What’s most intriguing about Ghosts of Mars is how it positions itself as a revisionist-revisionist Western. It doubles back on the trend of deconstructing the myths of the classical Western that started in the mid-‘60s and accelerated through the ‘70s. Carpenter’s retro-revisionism is a violent return to the “settlers vs. natives” story where the natives are presented as full savages who need to be wiped out entirely. Basically, it’s an old “pro-Cavalry” Western hidden under SF armor. This is a shocking direction to move the story, but it’s also sickly fascinating. Carpenter took his interest in the Western and went to one of its ugliest assumptions as an experiment. When Lt. Ballard makes the choice to return to Shining Canyon to annihilate the Martians, she bluntly states the reason: “This is about one thing — dominion. This isn’t their planet anymore.” It’s a chilling statement, and Carpenter certainly meant it to be. Unpleasant as it may be to consider, this regressive exploration of genre assumptions of Old Hollywood is where Ghosts of Mars most succeeds at being interesting — at least on an analytical level.

On the cinematic entertainment level, the human hosts for the microscopic Martians are the biggest success. Acting less like zombies than a horde of berserker Vikings, the Martian hosts look like a massive Norwegian Death metal band jacked up on a dangerous mixture of methamphetamines and marathon viewings of The Road Warrior. Bizarre and painful body-modifications, garish war paint, spiky metal accouterments, incomprehensible war shouts (again, think Vikings), and mining tools and industrial objects turned into horrific hand-to-hand weapons — it’s all wonderful schlock. I particularly like the buzzsaw gizmos the hosts hurl around to slice off limbs and heads. And the Martian leader, “Big Daddy Mars” (Richard Cetrone) is a terrific image: Marilyn Manson smooshed together with an orc.

A few suspense moments click. Each time a human host is killed, it releases its microscopic Martian “ghost” that drifts on the air until it enters another host’s ear. This is shot as a distorted, floating POV that adds an extra thrill in an otherwise ordinary corridor shoot-out: the MFP isn’t just trying to outrun the horde, but also the invisible invaders released from their bodies looking to possess them. It’s a touch of the tension of The Thing and its alien control/body horror fears.

Fun world-building details are sprinkled around, such as how signing up for a year-long contract on Mars works out to a two-year contract in Earth time and the difficulty rookies have breathing the partially terraformed atmosphere. Ballard’s weird vision of Elder Mars when she’s briefly possessed is one of the better visuals, and for a moment I could imagine Ghosts of Mars turning into pure Leigh Brackett. Carpenter still had some of his science-fiction groove.

This was the point in Jason Statham’s career where Hollywood didn’t quite know what to do with the bloke, so they tossed him into supporting parts for rough-edged seasoning. He works here as that, adding some much-needed grunt as Sgt. Jericho Butler. He’s the only character who gives me a sense of what Mars as a hellish dead-end world is actually like. Statham was originally cast as Desolation Williams, but was shifted to the part of Jericho because Screen Gems wanted a bigger name in the lead. In retrospect, this was a mistake — if Ghosts of Mars had been made seven years later, not only would Statham have played Williams, but the movie would have been marketed as a Statham action vehicle. (I have no idea if this would’ve been a better version of the movie, but Statham would’ve been fun to watch.)

Released to theaters during a time when special effects were rapidly advancing thanks to The Matrix, and with The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring mere months away, Ghosts of Mars received plenty of grief for its low-fi special effects. But I’ll stand up for them, because they’ve aged well. The CGI is wonky but sparse, and the model sets and practical effects have a charm to them the effects of Escape From L.A. lack. The KNB Effects Group created superb makeup effects for the human hosts.

The finale of Ballard and Williams marching out to face the Martian attack overrunning Chryse is a cozy callback to the end of Assault on Precinct 13. Remember that one? That’s a great flick.

The Negatives

So … how much do you enjoy scenes of Jason Statham unlocking doors or talking about locked doors?

The Martian marauders add buzz, but Ghosts of Mars needs a lot more schlocky energy. Or just energy in general, because this movie is a slog. No amount of cool concepts or crazy Martian Vikings can hold together a film that teeters drunkenly back and forth and occasionally passes out. Even the action scenes are choreographed and shot with a drowsy feel. It’s the Vampires drone — only a bit worse. (Although Ghosts of Mars does end stronger.) If the Martian hosts seem to be high on meth, the filmmakers are drowned in Nyquil. When Carpenter says he felt burned-out after this movie, I believe him.

The flashback structure is the biggest culprit behind the tedium. The story calls for a lean, forward-driving narrative style, but the habitual leaping back in time to relate events other characters have witnessed continually stalls the movie. Melanie Ballard provides an overall frame as she relates to a discovery hearing board what happened at Shining Canyon. All fine, that’s a classic noir trope and allows for a voiceover that can quickly skip over dull parts. But then other characters in Ballard’s story begin to provide their flashbacks, and once a character in a flashback narrates a flashback, taking us to Inception levels.

Most of these rollback scenes aren’t necessary or could’ve been integrated into a linear narrative. One or two, such as Dr. Whitlock (Joanna Cassidy) explaining the discovery of the Martian native’s in a vault, might have worked. But when they pop up every five minutes during the first half of the movie, they become both unintentionally humorous and pace-killing. You either want to laugh or groan each time another character starts up a story and the screen crossfades.

Those crossfades are their own problem. Carpenter, for whatever reason, employs a stylistic trick throughout the movie of dissolves within scenes: jump-dissolves, you might say. Perhaps this is meant to capture something about the nature of how memory works and create a dream-like sensation within Ballard’s narrative, but this has no thematic connection to anything in the story. Ghosts of Mars isn’t a meditation about the frailty or unreliability of human memory and storytelling. The strange crossfades are more like an affectation. They’re distracting and unfortunately contribute to the sleepy lull of the movie.

Natasha Henstridge was a last-minute replacement for Courtney Love, and she’s terribly miscast as Lt. Ballard. Her professional model look clashes with the setting as well as the character’s background as a burnt-out veteran and drug addict. I don’t believe Melanie Ballard is a woman on the edge, and the only effect the addiction appears to have on her is that it lets her overcome the Martian possession. (Why isn’t anything made of this discovery afterward? It’s never mentioned again when it should’ve driven the climax: everybody gets high on Ballard’s supply for the final fight with the Martians!)

There’s absolutely nothing interesting going on between Ballard and Desolation Williams. This is supposed to be the central relationship, the Cop and the Crook dynamic that made Assault on Precinct 13 so wonderful, but it’s a non-starter. Henstridge can’t play off the clowning antics of Jason Statham either and often seems uncomfortable trying to deliver her dialogue.

It’s not entirely Henstridge’s fault, however, because Lt. Ballard as written goes through character beats that don’t make sense. When Jericho Butler corners her in a room just because he decides it’s time for them to have sex, Ballard should simply gut punch him and walk out. Instead she goes right to making out with him despite showing no interest in Jericho before. And as much as the “dominion” line is the movie’s best bit of nastiness, it’s hard to believe for a second that Melanie Ballard cares enough about human domination over Mars compared to her immediate survival — or that anyone escaping on the train would agree to go back when they’re so badly outnumbered. (This is where bringing out the drug stash as a plan to defeat the Martians would have been an exciting turnaround.)

I understand why filmmakers were casting Ice Cube in serious roles at this point in his career. What else would you do with a legendary gangsta rapper? But it turns out he’s a natural comedic straight man, and as an actor he’s best known now for movies like Friday, Barbershop, and Ride Along. He feels out of place in the Napoleon Wilson/Snake Plissken role (yes, in early development, this was going to be a third Escape film), and he doesn’t even seem to be trying to generate chemistry with Henstridge.

The Matronage doesn’t work. The matriarchal society running Mars may have been one world-building piece too many for a movie already handling a heavy load with the Martians-as-Native Americans analogy. The Matronage is undercooked, underexplored, and seems to be there only to allow Desolation Williams to say script-flipped lines like “You got The Woman behind you,” or “I’ve been running from The Woman all my life.” As with other parts of Ghosts of Mars, this could have worked with Carpenter at a more energetic stage in his career.

One element where Ghosts of Mars is without a doubt a John Carpenter “worst” is the score. Nothing but heavy metal guitar strumming, over and over. It’s lazy and never seems to have any correlation to what’s on screen, which further hurts the underwhelming action.

The Pessimistic Carpenter Ending

It appears the Martians are going to retake their home world after all, but Ballard and Williams will kill a whole lot of those Warboy-wannabes before the end.

Next: The Ward

Ryan Harvey (RyanHarveyAuthor.com) is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate and has written for the site for over a decade. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires.” His stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla.

I always thought this is a criminally underrated movie. To me it looks like a movie based on a Leigh Brackett story she never wrote. Especially the whole background of the ancient Mars warriors and their re-awakening is straight out of Brackett. Anybody else seeing the parallels to some of her best work?

I rewatched it recently and it was … a movie. Not without its moments, but as a whole, nothing to write home about.

I’ve only watched this movie once (back in the grand old days of Netflix sending DVDs to your mailbox). I mainly “ordered it” to be a Carpenter-completist. It was one of the few Carpenter movies I had not seen. I had heard less than stellar things about the movie so I had low expectations going in. But I was presently surprised how creepy and engaging the movie was. I like the monster-is-coming-to-get-you style movies, especially when the protags fight back (e.g. Predator, Aliens, etc.).

Perhaps a re-watch is less than advisable.

I love this movie. I also love Van Helsing with Hugh Jackman, and League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Speed Racer, Dune, Watchmen, John Carter, and just about every other movie the internet likes to rip on. If you want to blame someone for these movies then blame me for wanting to watch them.

I can take it. Now excuse me while I go watch Ralph Bakshis Fire and Ice again.

I think most of the criticism of this movie is a response to what a letdown the second half is. The first half, with a gradually unfolding backstory of interplanetary horror, is creepy and wholly effective. And then it simply becomes a Mad Max clone, as the ancient ghosts of Mars turn out to be a bunch of leather-clad guys with chains and zero fighting skills.

Ah well. I still enjoy it.

I saw this film in the theater when it first came out, mostly because effective female leads in SFF action movies were rare enough then that I’d go see anything that had chicks kicking ass. This was the film that made me give up that rubric and get pickier. Henstridge didn’t fit the film, the anti-LGBT bits in the dialogue were gratuitous, doing nothing interesting for worldbuilding or character development, and the gross-out aesthetic is just not my thing. On that last count, the problem’s that I was the wrong viewer for the film, but not the other two.

Ah, well. We’ll always have Big Trouble in Little China, a film I love immoderately.

[…] Movie review on Black gate […]