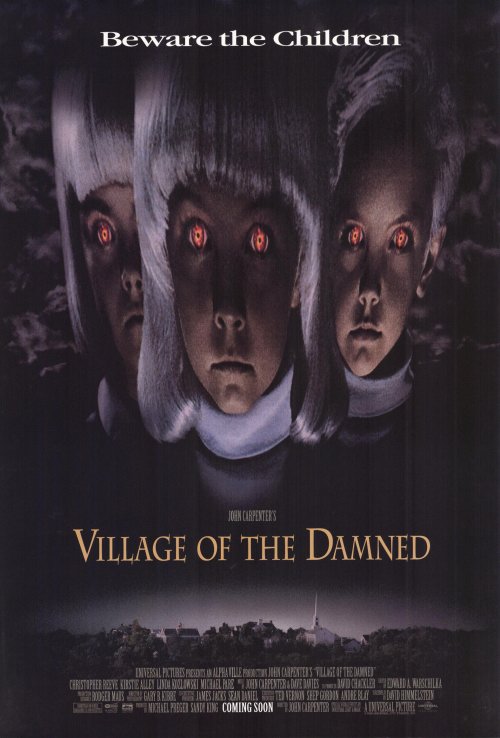

The Complete Carpenter: Village of the Damned (1995)

Here’s a crossover I want to see in a comic: Superman vs. The Village of the Damned. I just thought of that as I sat down to write because Christopher Reeve is in this movie. Hey DC, you’re welcome! You need all the help you can get.

Anyway, welcome to the late period of John Carpenter’s career. It’s downhill from this point, dear readers.

Village of the Damned came about when Carpenter and his producer Sandy King (whom he married in 1990) signed a contract with Universal and tried to set up a Creature From the Black Lagoon remake. When project planning bogged down, Tom Pollock at Universal handed Carpenter a script for a remake of the 1960 British SF/horror picture Village of the Damned (based on the novel The Midwich Cuckoos by John Wyndham) and asked the director if he’d make this before continuing with Creature. Carpenter agreed to do it as part of his contract.

Village of the Damned was a commercial failure when released in April 1995 after Universal rushed its release schedule. The Creature From the Black Lagoon remake never got the greenlight from the studio and faded away. So rather than getting a John Carpenter remake he was passionate about, sort of a follow-up to The Thing, we got a John Carpenter remake he was just trying to get out of the way.

The Story

A bizarre phenomenon strikes the Northern California town of Midwich: for six hours, every person and animal in the town and surrounding countryside falls unconscious. Pretty weird. But weirder is that a month later local doctor Alan Chaffee (Christopher Reeve) finds out that ten Midwich women are pregnant — and the conception date is the day of the blackouts. Dr. Susan Verner (Kirstie Alley), an epidemiologist studying the occurrence for the US government, offers financial incentives for the pregnant women to carry their children to term so the offspring can be studied.

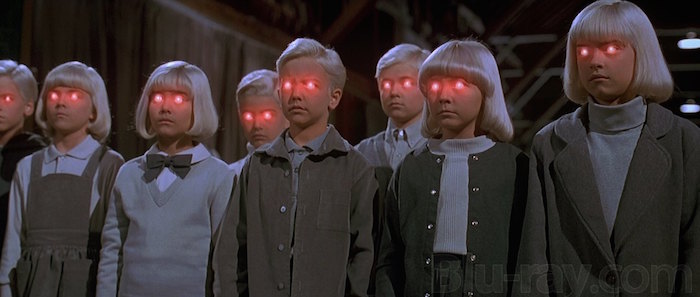

The children are born (although one is stillborn) and soon exhibit signs of enhanced intelligence and mind control abilities that lead to a number of suicides and “accidental” deaths in Midwich over the next ten years. Dr. Chaffee tries to reach through the cold, calculating defenses of the children, and finds hope in one, David (Thomas Dekker), whose “mate” among the children was the one who died. The other children, under the leadership of Mara (Lindsey Haun), advance their plans to defend themselves and execute their extraterrestrial imperative while making adults kills themselves in various oddball ways.

The Positives

As the finale of Village of the Damned starts, law enforcement descends on the barn the children are using as headquarters to subdue or possibly kill them. The children use their glowing eye mind-control powers to force the sheriff’s men, the state police, and the national guard to open fire on each other in a glorious burst of violent chaos, with guns unloading, a crashing prison bus (a nod to Assault on Precinct 13), and the kids somehow forcing a helicopter into a fiery crash. This scene delivers the only true jolt in the movie: a slice of B-flick over-the-top lunacy with no equivalent in Wolf Rilla’s 1960 film. It’s pure John Carpenter anti-authority craziness and almost makes the rest of the film worth it.

Christopher Reeve is a solid center for the movie, and the actor does his best to make something out of the script’s sloppy approach to theme and bring emotional weight to the picture. Reeve naturally exudes gentle authority and righteousness, which is ideal across from the children’s chilly amorality. It’s clear Reeve connected with the child actors and he makes the most of his time on screen with them, such as an effective scene with the conflicted David in a cemetery that ends with the boy gently taking his hand. Of course I’d believe this alien child would warm up to Christopher Reeve: he’s Superman! Tragically, this was the actor’s last role before his horse-riding accident, which adds a bit of extra-cinematic pathos.

But Reeve and the rest of the adult cast diminish when placed against nine-year-old Lindsey Haun as Mara, Dr. Chaffee’s “daughter” and the leader of the children. Haun’s ability to handle an ice-cold intellectual supervillain is impressive for such a young performer. She effortlessly works through dialogue no child should be able to handle: “If we coexist, we shall dominate you. That is inevitable. Eventually you will try to eliminate us. We are all creatures of the life force. Now it has set us at one another to see who will survive.” Haun is a match for any adult actor she shares a scene with, and her prickly, arrogant chemistry with Reeve and Kirstie Alley is fun. When Haun occasionally flashes an evil smile, she rockets to the top of the list of great “Creepy Kids” in horror films. That’s elite company.

The drama among the children because of David’s nascent empathy and his position as the “loner” is superior to anything that happens among the grown-ups. In fact, David’s subplot as he struggles with a humanity that’s foreign to the other children is the only interesting alteration made to the 1960 original that feels like serious thought was put into it. Mara’s one-on-one with David is the best dramatic scene — remarkable considering the actors are nine and six respectively:

Mara: You are thinking of the one who died.

David: She was to be my partner.

Mara: Yes, it’s true. Without a mate you are of less importance to us and your development of emotions is disturbing. We can’t leave you behind, David. It’s time we resolved this.

Good little scene, kids.

There’s one way that Village ‘95 surpasses Village ‘60: contemporary VFX allowed for improved spooky eye effects on the children. The original used hand animation on still frames when the children manifested their powers. For the remake, ILM went all out with startling dancing patterns in the children’s irises. This reaches a cool peak when Mara’s alien physiognomy manifests through her skin during the climax. This is a rare situation where CGI is a benefit to a science-fiction remake.

The score by Carpenter and Dave Davies is fine with a standout track, “March of the Children.” The cue isn’t used often enough, but its presence during the previously mentioned law enforcement massacre helps boost the scene.

The Negatives

Village of the Damned ‘95 has a dire reputation, often cited as one of the worst — if not the worst — film in John Carpenter’s canon. In his 2000 book The Films of John Carpenter, author John Kenneth Muir called it one of the director’s weakest films. Harsh criticism considering Muir later defended both Ghosts of Mars and The Ward.

I think Village of the Damned is better than its rancid reputation. If given the choice, I’d rather watch it than Memoirs of an Invisible Man or The Ward. But it still feels like exactly what it is: a contractual obligation. (Carpenter has said as much: “I’m really not passionate about Village of the Damned. I was getting rid of a contractual assignment …”) It’s directed with indifference, inconsistently acted, approached without much thought to updating the 1960 original for the mid-‘90s or borrowing from the source novel, and squanders potential in a dash to get to the end. This is science-fiction material that should have landed right in Carpenter’s zone, and yet it ends up as only somewhat better than a work-for-hire nothing like Memoirs of an Invisible Man. That’s not enough.

Universal can share some of the blame. The studio hustled the movie into theaters without allowing for last-minute tweaking from the director and cutting a number of sequences (such as the children bullying normal kids on a playground, a scene from the original that might have worked better in an update). It feels like the film is sprinting past ideas and conflicts with hardly a glance. Mark Hamill’s town priest was probably a victim of these cuts, since it seems a few major beats went missing from his character’s journey of going from fretting about finger paints to aiming rifle sites at a little girl’s head. It would also explain why such a fascinating actor goes so underused.

But too much of what doesn’t work about Village of the Damned is woven into the overall apathetic creative approach. No amount of adjustments or additional scenes could have salvaged it. There may have been a better cut, but not a much better one.

It’s absurd that the director who took another classic SF movie based on a literary property, The Thing, and turned it into a new classic could crash at essentially the same job thirteen years later. Most of the 1960 Village of the Damned is dumped into contemporary Northern California without taking advantage of the new setting. For example, the topic of abortion. Without a doubt, this is the single most important issue a 1995 version of Village of the Damned must wrestle with. Women are suddenly pregnant without explanation from what is essentially a phantom rape. The US government offers the women bribes (pretty cheap ones, too) to keep their babies for scientific study purposes—which is basically asking them to carry a rapist’s child to term. The potential conflict here is gigantic, with the specter that the government may force the women to give birth in the extremely likely case they refuse.

But the movie hand-waves this away in moments with a cheesy montage of the mothers sharing a hallucination of clouds and lightning as they stroke their pregnant bellies. This is supposed to suggest the alien force influenced them to carry the babies to term. So all the women decide against abortion, and nobody else seems to think this is at all peculiar. The movie simply marches on with its copy of the 1960s script and ignores the possible ramifications. This is what happens when you’re directing to fill a contract, not because you’re engaged with the material.

The town of Midwich is impossible to take as a real location because it’s another element left almost unchanged from the original film. This is a town in 1990s Northern California where everybody attends the same church. Huh? Maybe if it were a Unitarian Universalist Church and the script made a joke out of it, but this is so lazy. The alien kids arrive dressed like … 1950s British school children, because that’s what they looked like in the original. The nine children marching in lockstep wearing clothing they must have forced their parents to purchase from the Everything Gray and Drab Outlet store in Sacramento is an unintentionally hilarious sight. The silver-dyed hairstyles that look like wigs don’t help. (They aren’t wigs, but that most viewers can’t tell the difference is a problem.) Thank goodness the young actors have presence and ILM knew how to make their eye powers freaky, otherwise the children wouldn’t be intimidating at all.

Oh yeah, the film isn’t frightening or even tense. The children force a number of adults to kill or permanently scar themselves, but none of the violent scenes are noteworthy. Not even a boozy Buck Flower impaling himself on a broom wakes up the film. The finale where Dr. Chaffee visualizes a brick wall so the children’s mental penetrating powers won’t recognize his plan to blow them up with a time bomb in his briefcase is lifted almost shot-for-shot from the original, so even though it’s effective, the credit can’t go to the remake.

There are some interesting names in the cast — and we’ve got Peter Jason back once more, although without much to do as a man who knows he can’t be the father of his child. But the adult performers who aren’t named Christopher Reeve don’t come across as authentic and feel too much like a TV cast on a show that got cancelled midway through its first season. (And trying to pass off a twenty-five-year-old Meredith Salenger as a virginal small-town teenage girl? That’s sort of adorable.) This further makes it hard to think of Midwich as an actual town that’s under a paranormal assault. Kirstie Alley could’ve brought some sinister villainy fun to her badly underwritten part as the plotting government doctor (although the script is never clear what she’s plotting). Instead, Alley lets her yellow cigarettes do the acting while the child performers stomp all over her.

By the way, if you haven’t seen the 1960 Village of the Damned, I highly recommend it. It’s only $2.99 on Amazon, and Warner Archive has released a Blu-ray of it. Look, I’m trying to throw in something positive here at the end.

The Pessimistic Carpenter Ending

Dr. Chaffee sacrifices himself to blow eight of the children to smithereenies. David survives, escaping with his mother, indicating there may actually be hope for … something.

Next: Escape From L.A.

Ryan Harvey (RyanHarveyAuthor.com) is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate and has written for the site for over a decade. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires.” His stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla.

Another one which I’m not sure if I was even aware of as a Carpenter film until reading the article.

Trying to remember if I’ve seen the original; probably need to add it to Netflix regardless.

The original is absolutely brilliant. I never realized Carpenter did a remake.

[…] Movie review on Black gate […]

Nice analysis of the film. I remember this flopping when it came out in ’95, even though it had impressive visuals and the star power of Christopher Reeve and Kirstie Alley.

You’re correct in saying this movie tries to shove its way past the issue of abortion and women’s rights. Not that the film should have a stance on the issue per se, but when these matters are so obviously in front of us as they are in this movie, it’s playing dumb with the audience to try and ignore it.

Having said this, why wasn’t Debra Hill one of the producers? The attention she brought to Halloween (1978) by writing Laurie Stroud as a strong female character gave that movie dramatic weight and a needed counterpoint to the villain. That was sorely needed here, where the women are just vessels to keep the plot going, when we should be more involved in their plight.

The reviewers here really are mired in their own deep thoughts. This is a movie. You can take any work and

vivisect till there is nothing left. I relished every frame. Maybe it’s not a “genius” piece of work but did it scare? Yes. Did it entertain? Yes. Does it matter if all the newly pregnant women reacted in a predictable way? No. My

fellow critics…you are overthinking.