Revenge of the Literary Living Dead: Zone One by Colson Whitehead

Science fiction, horror fiction, fantasy fiction, mystery fiction — for most of their history, ghetto fiction, in that such stories and the writers who produced them were decidedly “second class” citizens of the literary world and so were kept confined to areas where no respectable reader (much less critic) would want to venture, primarily pulp magazines and cheap paperbacks with the kinds of covers that you would never want your girlfriend’s mother — or your mother, for that matter — to see.

Science fiction, horror fiction, fantasy fiction, mystery fiction — for most of their history, ghetto fiction, in that such stories and the writers who produced them were decidedly “second class” citizens of the literary world and so were kept confined to areas where no respectable reader (much less critic) would want to venture, primarily pulp magazines and cheap paperbacks with the kinds of covers that you would never want your girlfriend’s mother — or your mother, for that matter — to see.

But oh, how things have changed. While you’ll search the library shelves in vain for F. Scott Fitzgerald’s vampire novel or Norman Mailer’s alien invasion epic (which of course could never exist outside the realm of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies — style mashups, a tide that mercifully seems to have receded), a more recent breed of “literary” writers have produced books that not so long ago would have been beyond the pale for anyone but the most hopeless genre hack — in the eyes of the mainstream critical establishment, anyway.

But Philip Roth’s foray into alternate history, The Plot Against America, Cormac McCarthy’s postapocalyptic nightmare, The Road, and Joyce Carol Oates’ Dhameresque cannibal-killer fest, Zombie, to name only a few books, demonstrate that a new day has dawned.

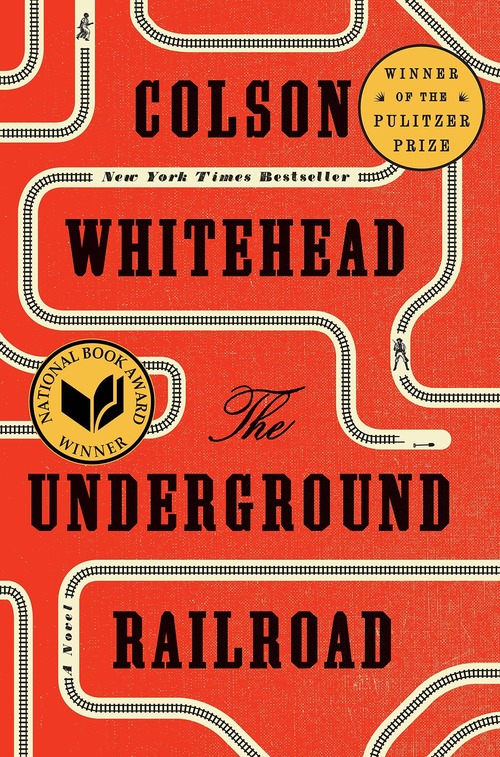

To more and more writers today, the old genre labels mean less and less; they’re going to write what they want in the way that they want, and artificial boundaries be damned. Such a one is Colson Whitehead, the author of four well-received mainstream novels published between 1999 and 2009, which established his reputation as a writer to watch. His most recent novel, 2016’s The Underground Railroad, fulfilled his promise by winning several major awards including the 2016 National Book Award and the 2017 Pulitzer Prize.

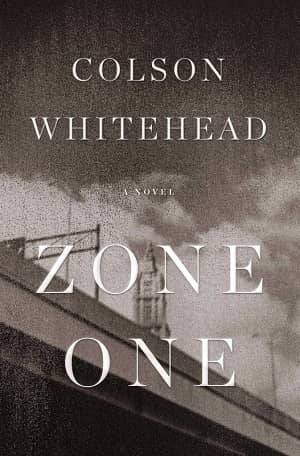

But between his first four novels and The Underground Railroad, Whitehead produced 2011’s Zone One, which was somewhat out of the literary mainstream (as it was once defined), being a full blown they’re-coming-for-your-brains zombie novel.

Sometime after an incurable disease has turned most of the world’s population into an army of flesh-eating living dead, Mark Spitz (an ironic title referring to the character’s inability to swim — we never find out his actual name) spends his days in Manhattan, working as a member of a civilian “sweeper team,” going from building to building, putting down the stray zombies that remain after a major clearance by the marines. He’s not exactly crazy about the work, but it’s a job, at least, and in a living-dead devastated economy, any job is a good job.

[Click the images to embiggen.]

Spitz spends one day out of seven on R and R back at Fort Wonton in Zone One, the cleared and secured section of the city. While there, he sees his own trauma reflected in his fellow sweeper team members, ambulatory casualties all, physically whole but psychologically maimed, and wonders how “clear” and “secure” the world can ever again be, especially when it must be rebuilt by emotionally wrecked survivors like himself.

Whitehead’s method throughout is to suggest a hidden affinity between the living and the living dead, as in this passage near the close of the novel:

The townspeople, of course, were the real monsters. It was the business of the plague to reveal our family members, friends, and neighbors as the creatures they had always been. And what had the plague exposed him to be? Mark Spitz endured as the race was killed off one by one. A part of him thrived on the end of the world. How else to explain it: He had a knack for apocalypse. The plague touched them all, blood contact or no. The secret murderers, dormant rapists, and latent fascists were now free to express their ruthless natures. The congenitally timid, those who had been stingy with their dreams for themselves, those who came out of the womb scared and remained so: These, too, found a final stage for their weakness and in their last breaths were fulfilled. I’ve always been like this. Now I’m more me.

This example should make it clear that Whitehead isn’t writing a standard “horror novel,” aiming at the usual horror effects, though the book has plenty of violent encounters and gory shocks. But more than just attempting (successfully) to generate fear and unease, Whitehead is clearly using the horror conventions to comment on everyday urban life — its mechanical materialism, its soulless routine, its mediocre ambitions, its increasingly tenuous and breakable human connections, and its helpless subjection to a lying and incompetent officialdom (during the three days covered by the main action of the book, the situation of the “real” people vis-à-vis the zombies completely collapses; not too surprisingly, the optimistic pronouncements of the authorities about all the progress being made turn out to be utter bullshit.)

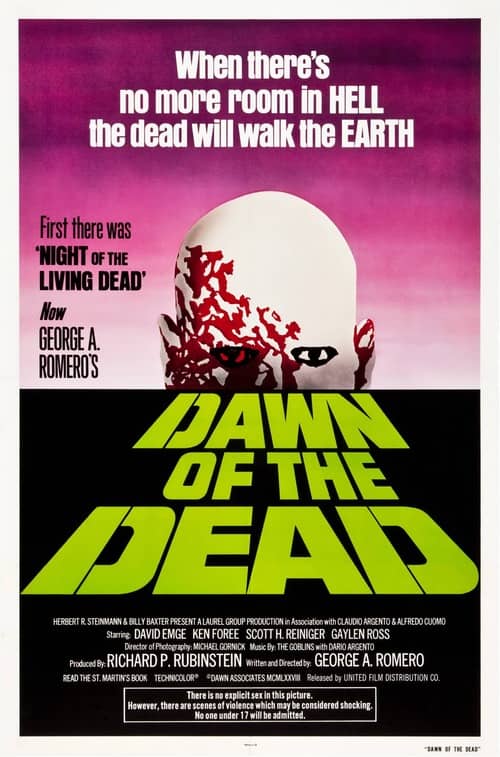

George Romero

It’s ironic that Whitehead uses his monsters to make a diagnosis that is essentially the same one that the father of the modern zombie, George Romero, made forty years ago in his living dead films, especially Dawn of the Dead. Only now instead of providing nothing more than red meat (literally!) for the hicks who frequent drive-ins and grindhouses, the method is seen to be a fit one for someone who could walk in the front door of The New Yorker offices instead having to sneak in via the service elevator, and the fact that a writer like Colson Whitehead wrote such a book at all is in some ways just as interesting as the book itself, excellent as it is. (The story has a cumulative effect that I found surprisingly affecting, and Mark Spitz’s final surrender to the inescapable imperatives of this Depraved New World — if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em — provides a perfect and powerful conclusion.)

Some “respectable” writers, when they approach genre material, feel that they have to somehow lift it up to their lofty level, and in stooping to get a handle on a zombie story, say, they wind up condescending to both the material and their readers. Either that, or they obviously feel that they’re “slumming,” and wind up muting or lobotomizing their own sensibilities. Whitehead doesn’t fall into either trap, however, and that’s one of the things — maybe the greatest thing — that makes Zone One such a success. Without embarrassment or self consciousness, he brings his literary gifts to the kind of story that rarely gets such treatment, while still respecting and retaining all of the qualities that make such stories appealing, not least, one feels, to Whitehead himself.

Colson Whitehead

Apart from being a fine novel and evidence of the erosion of old genre barriers (good news indeed), Zone One is also proof that the ravenous zombie has, in the last fifty years, moved from the ghetto of lurid comic books, low budget horror movies, and cheap paperbacks, to stand near the center of American culture. It seems that the living dead have metastasized into a perfectly apt metaphor for The Way We Live Now. The shoe fits — and that, I find, is more frightening than any gruesome novel or horror movie.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was a review of Doubling Down, or Just How Bad Are Ace Doubles, Anyway?.