Plants as Protagonists: An Interview with Semiosis author Sue Burke

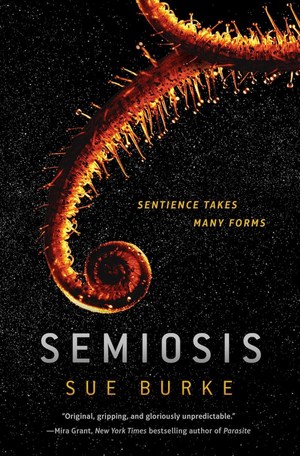

The science fiction world has been abuzz with the release of the novel Semiosis by Sue Burke. Known for her short stories in publications such as Interzone and Asimov’s, this Clarion alumnus is now making waves with her debut novel, out from Tor this month. James Patrick Kelly said it’s “a first contact novel like none you’ve ever read… The kind of story for which science fiction was invented.” David Brin wrote, “In Semiosis, Sue Burke blends science with adventure and fascinating characters, as a human colony desperately seeks to join the ecosystem of an alien world.”

The science fiction world has been abuzz with the release of the novel Semiosis by Sue Burke. Known for her short stories in publications such as Interzone and Asimov’s, this Clarion alumnus is now making waves with her debut novel, out from Tor this month. James Patrick Kelly said it’s “a first contact novel like none you’ve ever read… The kind of story for which science fiction was invented.” David Brin wrote, “In Semiosis, Sue Burke blends science with adventure and fascinating characters, as a human colony desperately seeks to join the ecosystem of an alien world.”

Those recommendations would be enough for me to buy a copy if I hadn’t already read it several years ago. Sue and I used to be in the Madrid Writer’s Critique Group here in Spain before she moved back to Chicago. The early draft I read fascinated me with its tale of human colonists settling on a planet only to find that is already inhabited by intelligent life… plant life. I caught up with Sue to talk with her about her new publication.

What was the seed of an idea that grew into a giant, sentient plant?

Seed… I see what you did there.

It started back in the mid-1990s when a couple of my houseplants attacked other houseplants. One vine wrapped around a neighbor, and another vine tried to sink roots into another plant. I began researching botany and discovered that plants are active, aggressive, and fight to the death for sunlight. They have weapons and cunning strategies, both offensive and defensive.

For example, strangler figs (several varieties of Ficus) start as seedlings germinating up on tree branches and trunks in jungles, and as they grow, their roots wrap around the host tree and eventually strangle and kill it. The fig starts halfway up to sunshine, which is an advantage. But how do the seeds get up there? Birds eat fig fruit, and the seeds have a gluey covering that sticks to a bird’s feathers when it defecates. The bird wipes off its vent on tree branches and trunks, where the seeds adhere and germinate.

To combat this, the kapok or red silk cotton tree (Bombax ceiba) grows spike-like thorns on its trunk and branches. Birds would risk injury to clean themselves there.

Do roses have thorns for the same reason? No. Roses clamber over other plants to pursue light, and they anchor their thorns into them to facilitate climbing. Like the strangler fig, they might mercilessly kill other plants in the process, in this case by starving them of sunlight.

The plant kingdom is nasty. I had possibilities for conflict. I only needed a story.

With a plant as a major character, what kind of adjustments did you have to make for your narrative and characterization?

Obviously I had a character that couldn’t communicate humans easily, so I had to invent a way for it to do that. And this character was immobile, so if it was going to take part in any action, it had to already be growing where it happened.

On the other hand, a plant as a protagonist offered some advantages. Like “Pando,” an 80,000-year-old 106-acre clonal colony of quaking aspen in Utah, I had a protagonist who could be very old and very big. Since plants are aware of their environment, it could offer something close to omniscience, which can be an effective narrative tool. In addition, plants can make a wide variety of chemicals and communicate with each other, so the protagonist had allies and potential weapons. It was also naturally active, aggressive, and willing to kill without mercy.

In what situation would all this be decisive? That is Chapter 6, the climax of the novel. Like any writer, I had to pick the dramatizations that served my story, and in this case, I had both constraints and freedoms.

I remember during our writer’s group meetings you were full of interesting and bizarre plant facts. What oddities made it into your novel?

Besides Pando, there are a few passing references to “poop plants”: plants that look like feces to avoid predation. This was inspired by the Euphorbia decaryi, a succulent from Madagascar that drops its leaves during its dormant period. Its whitish-brown stems form a little mound on the ground. I’ve seen it, and it really does look like a pile of turds.

A plant I invented, the blade-leaf irises, are loosely based on stinging nettles (Urtica dioica). These Earth plants have glassy needle-like hairs that poke into your skin to inject chemicals that make you itch. If plants could create razor-sharp glass for that, they could make it for even uglier purposes.

A tree I invented, the locustwood, can choose its sex, and one of a grove becomes the male and the rest are female. Certain kinds of holly shrubs (Ilex species) do that.

And sometimes plants invite us to eat them.

Strawberries turn red to tell us to eat the fruit so that the seeds, which if uncooked can survive our digestive system, will be deposited somewhere to grow along with fertilizer.

Grass grows underground, sending up tender, tasty, easily replaced leaves. If grazers like cattle eat the leaves or lawnmowers cut them off, in the process the animals or machines also cut back weeds, which often die, allowing the grass to dominate a field.

Animals can serve plants in accomplishing their goals – that is, a plant-based character might find it natural and proper to manipulate animals.

What are your thoughts on the relatively new subgenre of ecopunk? How does Semiosis fit into this movement?

I’m glad to see ecopunk. I think it asks important questions about our future, something science fiction excels at. The Anthropocene is here: a new epoch on Earth in which humans affect the ecology, including climate change. What will that mean? How will we cope? Can we do it right – that is, can we find a way to a hopeful, even optimistic future?

I wrote the book before that movement took off, and while it’s not a close fit, it does share the idea that humans are deeply involved with and accountable to their environment. In the case of my novel, the environment can fight back, so humans are forced to behave responsibly.

What more can we expect from you in the coming year?

My story “Life From the Sky” will appear in the May/June issue of Asimov’s magazine, dealing with toxic social media. My novella “Who Won the Battle of Arsia Mons?” about an entertainment-driven robot fight on Mars is one of the five finalists in the Reader’s Poll at Clarkesworld magazine; you can find links to all the stories and voting, which closes February 24, here.

As for Semiosis, a manuscript for a sequel and the outline for a third novel have been submitted.

And I’ll be at Worldcon in San José, in case anyone wants to say hi. I like to meet new people.

Sean McLachlan is the author of the historical fantasy novel A Fine Likeness, set in Civil War Missouri, and several other titles. Find out more about him on his blog and Amazon author’s page. His latest book, The Case of the Purloined Pyramid, is a neo-pulp detective novel set in Cairo in 1919.

[…] Recommended reading by Sue Burke: Semiosis (my review)Interview with the author about Semiosis: https://www.blackgate.com/2018/02/21/… […]