RBE returns with a WWE-style SmackDown: Challenge! Discovery

Ahem. It’s been a tad longer than realized: almost exactly 4 years later, RBE reignites. What better way to light the conflagration then with Battle Royale?

Once upon a time…

…way back in 2010, RBE introduced the concept of CHALLENGE! anthologies with a dual purpose: fund-raiser for RBE and platform for heroic storytelling. I did a lot of research beforehand, striving to determine whether the concept would be beneficial or harmful. I decided that with transparency from the onset, it was a strong method of achieving both goals. I solicited and received positive endorsements from mentors and others I respect in the publishing, writing, and heroic worlds. My intentions were confirmed and supported, first by artists and judges willing to partake, and then by actually receiving submissions. Then I failed to deliver.

I am here to rectify that. RBE always pays its debts.

Most importantly, I wish to express sincere gratefulness to all participants for their patience. It’s been a long time coming, and my personal debt to them all will only modestly be repaid once copies of the book are in their hands. RBE is all about HEROES, and I present to you those who accepted RBE’s first CHALLENGE!:

- “Witch with Bronze Teeth” by Keith J. Taylor

- “Fire Eye Gem” by Richard Berrigan

- “Inner Nature” by John Kilian

- “The Ash-Wood of Celestial Flame” by Gabe Dybing

- “Someplace Cool and Dark” by Frederic S. Durbin

- “The Writing of “Someplace Cool and Dark”: A Behind-the-Scenes Perspective” by Frederic S. Durbin

- “World inside the Walls” by Frederick Tor

- “In the Ruins of the Panther People” by Daniel R. Robichaud

- “The Serpent’s Root” by David J. West

- “A Fire in Shandria” by Frederic S. Durbin

- “Cat’s in the Cradle” by Nicholas Ozment

- “Attabeira” by Henry Ram

Cover art was provided by V Shane, who joined author Alex Bledsoe, and editor John Klima (most famously of Electric Velocipede) as judges.

So what is a CHALLENGE! anthology? Glad you asked!

RBE’s CHALLENGE! anthologies are calls to competition issued in part to engage respondents in a contest of heroic storytelling and in another part to ensure the validity of RBE’s byline: Putting the HERO back into HEROICS! To partake in such contests is to dare to accept an invitation not to decide superiority but to define heroics, defend heroism, and determine HEROES.

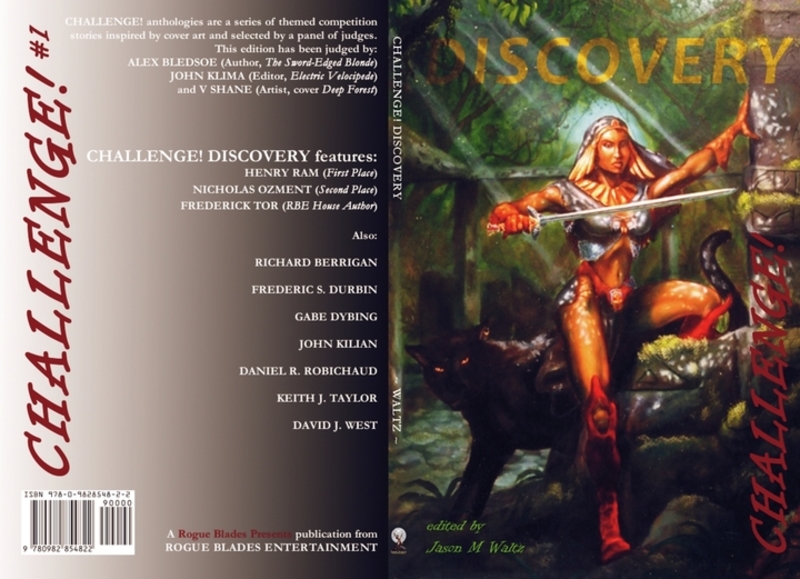

Accepting a RBE CHALLENGE! requires commitment to write to theme and contribution to support the cause. CHALLENGE! titles are intended to perpetuate tales of heroes and raise financial support. These anthologies revolve around their cover art and a single-word title that art inspires within me, the editor. Authors rising to the CHALLENGE! are encouraged to deliver the strongest heroic adventure the combination of art and title rouses within them. CHALLENGE! anthologies are also taken to a higher standard by being judged by professionals on two standards only: (1) How well each story delivers quality heroic adventure, and (2) how well each story uses the cover art and title. Judges will always include the cover artist as well as one recognized editor and one recognized author of heroic tales.

RBE is about HEROES, and heroes exist in every genre. Fantasy may be our flagship, but our fleet is full, and it is strong, it is larger-than-life, it always surges forward, and it endures. HEROES are embedded in the world’s soul, integral to every cultural fabric. They dominate our legends from the men and women of history to the denizens of our literary worlds. The stories we tell each other begin and end with HEROES. These pages are beyond genre; they’re simply heroic.

So what’s in this particular CHALLENGE!? The creations of the writers stimulated by this cover and title to accept RBE’s call to put the HERO back into HEROICS. How did they choose to deliver? Did they deliver? Go ahead, judge for yourself. I dare you to DISCOVER if they created HEROES that live and breathe, and steal readers’ hearts. If you are a reader who loves DISCOVERING new HEROES, this book is for you.

You may notice among the names one that appears thrice. Submissions move through the competition blind and everyone is welcome to submit as often as s/he desires. Our friend Frederic S. Durbin not only submitted two tales, but placed both of them in the Top 10! Fred was so excited that “Someplace Cool and Dark” was accepted, he asked if he could share the story behind the story. Of course! So this edition of CHALLENGE! contains an extra-special nonfiction piece that’s just as fun to read as the story it discusses. I’ve heard delightful stories of Fred reading “Someplace Cool and Dark” at various conventions and events over the last few years, and I know we’ve all been awaiting the day more readers can enjoy this adventure. With Fred’s permission, RBE is proud to share his exploration of the CHALLENGE! DISCOVERY art and theme below.

As for DISCOVERY — I hope you relish the art, ponder the title, and find joy in a new HERO. Mostly, I CHALLENGE! you to read it. Now here’s Fred:

‘The Writing of “Someplace Cool and Dark”: A Behind-the-Scenes Perspective’

FREDERIC S. DURBIN

August 31, 2010THE OTHER TITLE I considered for this story was “Six.” That number seemed to reverberate through it: the gang of six that has taken over Discovery; the six fingers that alert the good guys to their presence; the prominence of six-shooter pistols and the need to reload after six shots. It struck me that anyone who really needed to use an 1800s revolver in daily life would have had to internalize that rhythm of six—life might depend on it. [As Dirty Harry famously asked: “How many shots have I fired? Five . . . or six?”] Actually, I understand that under normal circumstances, most guys in the real Old West kept only five bullets in their revolvers, with the firing chamber empty. Five shots was usually plenty, and that way if the gun got jostled or the hammer snagged on something, they wouldn’t shoot themselves in the leg.

What’s more, this story was created in six days (August 25-30, 2010)—six days, just like the world itself as recounted in Genesis. During six days of the hottest summer in recent memory, I wrote the piece for the Rogue Blades Entertainment “Challenge!” contest—four intense days of writing and two of further research, editing, rethinking, and tweaking. (For the contest, you had to study a painting of a female warrior holding a sword, in a jungle with stone ruins, and a black panther behind her; you had to use that picture in some way and also the theme “Discovery.” Beyond that, you could write in any genre—fantasy, sf, horror, humor, romance, or anything else—as long as it was a story of heroic action adventure. Why did the picture make me want to write a western? I don’t know. I have weird reactions to ink-blot tests, too.)

The writing was done outdoors in the daytime and indoors during the still-sweltering nights, all on the AlphaSmart Neo—and a wonderful memory it will always be, the blur of glorious heat, blue sky, glowing sunlight, warm shade, and crickets thundering in the dark. There’s a particular “outdoor” quality to the story—a hot, summer quality—that I’m sure was made possible by the physical circumstances of the writing. The story is like a souvenir of this summer.

So I thought long and hard about “Six” as a title. I considered making the gold coins have a design of six dots, and letting the carvings in the cave of the “Old critters” have some kind of “six” motif, linking the primordial past to the present. But in the end, I decided to go with my first idea, and the story became “Someplace Cool and Dark.” That’s really what it’s about: Ovid Vesper’s journey toward “home,” or his destiny, whether it’s a permanent destiny or not. (Nothing seems very permanent in his life, which reflects the Old West as well as our own experience in this world. We’re all just passing through, but at least by the end of the tale, Ovid has found himself a good place to settle for a while. I love his optimism, how even in the face of death, he grins about what a good friend Charley is—and then when they’re inevitably going to part ways, he’s still happy. There’s a wonderful maturity to the worldview—the best parts of maturity—a calmness, an equanimity.) (Even if you’re familiar with the word “equanimity,” I strongly urge you to look it up and think about the meaning. That, I believe, is what we should strive for in life, especially by the time we get into our forties. Equanimity.) The title is also ambiguous enough to be intriguing. It sounds basically positive, but there’s a slight menacing undercurrent, especially since the story opens with Vesper descending into a black, cold cave that is anything but pleasant. So the reader wonders: is a cool, dark place going to be good or bad?

In general, I’m not a fan of “weird West” stories—but this one insisted on being what it was. Though it was in my original concept, I came close to not including the part about the strange, cold stones in Ruby’s saloon. In the end, I reinstated them, because for one thing the ending felt too abrupt, and I wanted to give it some length; but more importantly, the story felt unbalanced without them. At its heart, it’s a western: Ovid and Charley take a stand against the bad guys. But it begins in the weird, with ancient races and monsters. So I felt it needed to end in the weird, too, in order to come full circle and remind the reader: “This is not quite the Old West as we know it.” Also, the presence of those stones gives a hint as to why the town is named Discovery. Not a full explanation, but a hint—there are things nearby to be discovered.

An Old West in which there are elder horrors, too—what a canvas to work on!

Something I especially like about “Someplace Cool and Dark” is what it says about the nature of the human struggle: there are dangers both natural and unnatural; there are monsters that prey on humans; but some of the worst monsters are the human ones. (And when you really think about it—Ovid goes down into monsters’ lairs and picks fights with them. He slaughters them for gold. He acknowledges they’re right to be angry. From one perspective, he’s a kind of monster. He’s not the cowboy of the Saturday serials of yesteryear; Ovid Vesper, like Han Solo, shoots first.)

The research for the story was a lot of fun. I’d originally intended Ovid’s horse Jack to be a palomino. But I looked up that word and found that it didn’t come into use until the 20th century. So I still described him the way a palomino looks, but I didn’t use the term itself.

It’s always fun looking at gun collectors’ sites, choosing an arsenal to arm characters with. Just as we writers don’t refer to our “writing machines”—rather, we say “Neo” or “Mac,” etc., I figured that in a world of guns, people would be inclined to use specific names such as Schofield or Colt, not just “pistol,” because every make and model has its own characteristics. (Remember, Inuits have all those different words for different kinds of snow.)

For me, a story is usually not fully alive until the natural world is well represented, so I spent some time on gardening sites, studying trees and plants of the Southwest. It’s possible that I’ve got things growing in proximity to each other that actually don’t, but plants do have the quality of turning up in surprising places, and of course they ignore the lines humans draw on maps. Anyway, the effort for verisimilitude has been made. (The location of the story isn’t specified, anyway. I won’t tell you what I think.)

Dialect was a fascinating challenge. What seized me right from the start was Ovid’s voice, and I knew I had to let him tell the story. How he tells it is as important as what happens. We don’t really know how people in the Wild West talked—we don’t have recordings, and no one alive now remembers it. We have examples of what people wrote, which is a strong indicator, but written speech is a little different from spoken speech. We can make intelligent guesses. Ovid’s diction is probably a mishmash of Old West, rural Illinoisan, my paternal grandmother’s Tennessee roots, and the strange habit my mom had of lapsing into bad grammar when talking with her sisters or old high-school friends. (She was a teacher and spoke quite correctly most of the time; I never understood why bad grammar seemed almost a point of pride with all of them when they got together.) But it’s okay that we don’t know how cowboys spoke, because people in the Old West were from all over the place. A lot of them weren’t born there.

The trick with dialect is to suggest its flavor without overdoing it. Till the very end, I agonized over whether to go through and change all the “-ing” endings to “-in.” I didn’t want to use apostrophes, but I know Ovid wouldn’t actually say “-ing.” In the end, I left the –ings alone, for the sake of not distracting the reader. Too many altered words on the page simply make things harder to read, and I believe there are enough of Ovid’s speech patterns shown that the reader doesn’t really hear “-ing” even though it’s written.I went over every line, every word, asking myself if it sounded authentic. I changed things back and forth and experimented with different words. When Al Pacino played the blind character in Scent of a Woman, he got so used to mentally “shutting off” his eyesight that, as the story goes, when he tripped and fell down during the shooting of the film, he forgot to close his wide, staring eyes. He had effectively overridden his blink reflex. In his impact with the ground, he scratched one of his corneas and had to spend some time recovering—that’s dedicated character acting! But that sort of happened to me in these six days of “Someplace Cool and Dark.” I had to learn how to talk like Fred again afterward!

On the one hand, many people in the 1800s had a much better, richer vocabulary than we make use of today. On the other hand, men like Ovid probably didn’t have much schooling. So I tried to reach a balance between substantial Latinate words and cowboy Anglo-Saxon. I’m sure the reader will find some uneven patches. In general, I think the whole gunfight sequence is almost perfect—I’ve never been prouder of anything—but when Ovid is describing scenes such as the interior of the cave, he gets a bit more literary.

He reports Conroy’s high diction faithfully. I know that requires a suspension of disbelief, but I felt the reader needed to hear Conroy’s words. I think that’s a legitimate use of artistic license.

This is the first story in which I’ve dropped inhibitions and allowed coarse characters to talk coarse. (Man, was it fun!) It was necessary: there’s just no way to write about these characters without the colorful language they would have used. I could hear their spoken lines in my head more clearly than with anything else I’ve written. There were two occasions on which I reined them in, probably to the detriment of the story—but there are some places I’m just not ready to go.

All right, you’re curious now. The first was Ovid’s thought about how Conroy “should have been a Pinkerton.” In my head, Ovid very distinctly used the f-word as an adjective right before “Pinkerton.” The line is okay without it, but that is a case of my interference. I apologize for deliberately breaking off a piece of the fossil I was excavating. The second case was the first line Ruby says. What I heard her say was much more graphic. I think I finally found the ideal compromise. Now she says “a pair of men who don’t bend over and take it.” If your sensibilities are more refined, you can understand that to refer to a “whuppin’.” But I don’t think that’s what Ruby means. At least the new line is publishable.

Friendship and loyalty are as fundamental to great western stories as are courage and the willingness to do the right thing. In my opinion, the very pinnacle of this story—my favorite part, and one of the two or three best lines that have ever come through my keyboard—is Charley’s last spoken line: “Get out of my way, you ornery shit.” That sentence works on so many levels that I can only say it was inspired. It was a line I heard Charley say; it wasn’t one I wrote for him. First of all, it sounds perfectly authentic. (And I count it as a miracle that I could use the word “ornery” in a line that sounds authentic.) Second, it expresses what kind of man Charley is: he and Ovid are at the end of a losing battle, and they know it, but Charley’s attitude is still one of “Get out of my way so I can shoot those sonsab**ches.” The fight is never out of him. Ruby is certainly right in her assessment of this pair’s character. I love the fact that neither Charley nor Ovid seems the least bit afraid of dying. Oh, certainly they’re fighting to live; I’m sure their hearts are pounding and their self-preservation instincts are in overdrive. But they don’t give in to fear; they don’t give it a place. They’re busy living, and when the time comes, they’ll get busy dying. Finally (and most importantly), the line reveals the friendship between the two men. By saying “Get out of my way,” Charley is acknowledging that Ovid is planted between him and the shooters. Conroy and Ring will have to shoot through Ovid to get Charley, and Charley is saying “Thank you.” The line rings absolutely true concerning the way men relate to each other and express themselves—especially men like these two, who don’t have to say much. If I’d tried to write this as a teenager, I would probably have had Charley say, “Go on . . . [gasp, gasp] . . . save yourself! Don’t worry about me!” and Ovid would have said, “I ain’t a-goin’ nowhere.” [etc.]—I’m glad the story waited to find me until I was ready for it.

A note for writers: in any kind of a prolonged fight scene, it’s good to have sharply differentiated participants, and extremely useful if they have names. This fight flowed well for several reasons, and most were minimally-conscious decisions on my part. First, all the bad guys don’t attack at once, which allows Ovid and Charley to do as well as they do. (It’s also realistic, because no one is expecting a fight; Conroy doesn’t have all his troops mustered.) Second, the last two enemies are the most strongly characterized, and they’re the two with names known to the protagonists. That made it awfully easy to write. At all costs, it’s best to avoid identifying characters with awkward labels like “the man in the checkered shirt” or “the man with the greasy hair.” Nothing slows down the action faster than writing all that.

I know—it’s regrettable that “the Mexican” and “the Apache” are characterized only by their ethnicity. But there’s only so much you can and should do in 9,000 words. Those two people groups were distinct presences in the Old West; I did my best to use them well.

I didn’t think long or hard about any of the characters’ names. They all just came naturally and almost immediately.

Ring Linder is the professional killer. He’s completely in control through the whole fight, and he’s the one participant who doesn’t get even slightly injured—until, of course, the wild card Ruby shows up. He allowed me to throw in what sounds like a typical bit of Wild West lore—the story about how Ring puts a shot from thirty paces through the wedding ring of each man he kills. I physically figured that out on the day I wrote that scene: originally, I’d written “fifty paces.” On my daily walk, I started at an electric pole and measured out fifty paces. I turned around and looked back at the pole, and I decided that was just too far away—I would hardly even be able to see a wedding ring nailed to it. So at the next pole I tried it again with twenty paces, and that was too short. I went on to thirty, and that was just right: still highly unlikely that anyone could do it consistently with an 1800s pistol, but not beyond the realm of possibility. (And Ring may not actually even do it, or maybe he did it once; as Ovid suggests, the legend may be only that.) So—introducing the character with the rumor of how formidable he is helped to make him distinct and menacing for the reader. When Ring shoots Charley through the arm, I don’t think that was a case of missing his chest; I think Ring put that bullet right where he intended to, because he’s under orders from Conroy to capture the two men alive (so they can lead the way to the gold). Conroy has doubtless given this order to all his men, but most of them aren’t “surgeons of the gun” like Ring. I think Ovid and Charley are in real danger from all the other shooters, who are riled up and in kill mode.

Xavier Conroy—that name seems so perfect to me that I almost wonder if I’ve heard or read it somewhere. It sounds exactly like who he is: “Xavier” suggests that he’s from far away, and it makes him sound uppity and grandiose. “Conroy” is “con” plus “roy”—“roy” suggesting “king,” and “con” adding the nuance of “con game” or “con man”—he’s a deceitful, unrighteous king. [My apologies to people with that name: I’d bet its actual derivation is much nobler. All those people are welcome to create a despicable outlaw named “Durbin.”]

Of all the characters I’ve ever written, Conroy is one of the most vivid in my mind. I almost wish this were a novel so that he could have done more, because it was fascinating for me to watch him. I can hear his voice clearly. Every line he says, I know exactly how he would say it. (No, I have no idea how or if the ancient Assyrians punished liars—but if I’m lucky, they did and it was bad.)

The old-timer…He’s a true unsung hero of this showdown. First, he quietly warns the protagonists of the danger they’re walking into, and he tells them the number of men they’re up against—crucial information in a gunfight. And it’s the old-timer’s arrival on the hotel porch that gives Ovid the break he needs to shoot the gunslinger. The timing may have been accidental, but I highly doubt it. I’m more inclined to think the old-timer stood at the corner of the porch, waiting for the precise moment when Ovid could benefit from a diversion. Of course the old-timer is taking a chance—he doesn’t know that Ovid and Charley will put up a fight and throw off the yoke of Conroy’s tyranny from the town—but he’s got nothing to lose. It’s worth a try.One of my favorite phrasings in the tale is how Ovid and Conroy “miss each other spectacularly” there in front of the hotel.

Finally, there’s Ruby. Believe it or not, when I put that sign on the front of the saloon, I didn’t yet know that would be the woman’s name. I just liked the “Old Westiness” and silliness of a saloon called the Ruby Diamond. By the time I got to the point in the story where I started paying attention to the woman who was about to make her entrance, it occurred to me: “Oh, that’s her name!”Ruby haunts me like the Amazon in his visions haunts Ovid. She’s another reason I wish this were a novel, so I could answer more questions about her. “Ruby Diamond” is almost certainly not the name she had from infancy, so, like many in the Old West, she has reinvented herself; she’s come from somewhere to this town, from some other life, which probably wasn’t good (since she left it). How did she come to own the saloon? What was she doing in a cave that led her to find the cold stones?

I wonder if some readers will dismiss her as a deus ex machina ending. (Or, in her case, a “dea” ex machina?) She’s not, of course: from the beginning of the story, the question is planted—who is the Amazon that Ovid keeps seeing in his head?

It’s fun for me to imagine the gunfight from Ruby’s perspective. She’s probably had a rough time in the weeks or months since Conroy’s arrival in Discovery. Conroy would certainly have noticed her, and she’s probably been walking a precarious line—striving to keep her independence, but making compromises for survival. If I had to speculate, I’d say that Conroy’s men get a lot of free whiskey at the saloon, but Conroy has ordered them not to touch Ruby because he wants her for himself, and he’s confident that he can eventually win her over the hard way; he’s enjoying the game. Ruby isn’t. She’s itching to be free of the despot. Whenever anyone new arrives in town, everybody pays attention. Conroy’s men herd newcomers down to Conroy’s headquarters so he can interrogate, intimidate, and take from them what he wants. But also, whenever any stranger shows up, the townspeople must be hoping for deliverance.

When the fight breaks out, Ruby would be watching from the saloon—it’s straight across from the hotel. Her heart must leap when two of the gang are gunned down. There’s hope! Some of Conroy’s stray shots come into the front wall of the saloon. It’s fortunate that Ruby and her customers aren’t hit. Ovid and Charley ride off on their horses. Ruby, like Conroy, assumes they’re clearing out of town; that’s probably the only thing that prevents her from snatching up her guns and going out to join the fight.

But the heroes do what no one expects: they stay in town—two rabbits that turn right back on the pack of dogs. Gunfire sounds from various streets. Ruby stands in her doorway, listening to what Conroy’s men are shouting. I would imagine that at this point, there’s a disagreement in the saloon. Ruby grabs her guns and urges her clientele to seize the opportunity: “Them boys need help! This is what we been waitin’ for! Who’s comin’ with me? Frank? Everett, you can shoot!” (Relax, she says it better than that.) Unfortunately, the guys hanging out in the saloon at midday aren’t exactly the town’s bravest or finest. Most care about Ruby and try to calm her down, reminding her that Ring Linder’s out there. Ruby struggles against those holding her arms, kicking chairs over and calling the men “yeller sons-a-cusses.” Probably she gets one arm loose and punches some well-meaning fellow. (She apologizes to him the next day.)Someone yells, “It sounds like they’re over at the livery stable!” Maybe some guys slink out and go over that way to watch from around corners—I don’t know. But at some point, hearing all the blasting and ricochets, Ruby will not be restrained—wild horses can’t hold her back. She charges across town with her twenty-gauge (and pistol). People peeking out of windows say, “There goes Ruby! She’s gonna get herself killed!”

Since all three remaining bad guys survive long enough to get to the corral, I don’t think Ruby shows up until the stable siege is over, and the heroes are running into the corral. She ducks behind the abandoned marshal’s office, takes the shortest lane between some houses, and comes out facing the corral. She is just drawing a bead on the guy in blue when Ovid shoots him. (Conroy is dashing through the center of the stable at this point, and Ring is on the far side of it from Ruby.)

Ruby lowers her gun and advances. With the shotgun, she has to be as close as possible. Conroy emerges from the barn; Ring joins him via the far gate. Ruby comes up to the corral fence just slightly behind them, and to their left. If they weren’t so intent on their prey, they would see her. She’s in plain sight and has just run across open ground. The dead man in blue is hanging on the gate about a dozen feet to her right.

On Conroy’s right, Ring is slightly farther away from Ruby than Conroy is. Ruby knows she needs to put Ring down first, because if she spends any time on Conroy, Ring will whip around like a striking snake, and he will not hesitate to shoot a woman. So she sights across the fence. I’ll bet she actually props her arm on the top rail, with the gun sticking out into the corral. She empties one barrel into Ring, moves her finger to the other trigger, and empties the second one into Conroy before he even turns around.

And that is that.

[See how real this is to me? It sounds like I’m describing a historical event!]

The story is partly a Lovecraft homage without being a true Cthulhu Mythos story. I don’t think the “Old critters” here are Lovecraft’s Old Ones, but you never know. Lovecraft never mentions that they gathered gold or made coins. But I did borrow the idea of their “patterns of dots” from Lovecraft’s “At the Mountains of Madness.” And of course, the mind-warping “impossible geometry” is from Lovecraft.

Pig-spiders—yes, a ridiculous notion, and it would probably not be a good idea to represent them visually in a movie. But in a story, I think the notion is creepy. (A lot of ludicrous, silly things become horribly unsettling if you think about them.) Why did I do that? Well, spiders are indisputably scary. Personally, I think pigs can be, too, in the right context. Why not put the two together? They’re like Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups!

It’s also a way to help with the early characterization of Ovid. He deals matter-of-factly with these bizarre creatures, all the while explaining to us what he’s doing. It just seemed like the right way to go about the story.

I don’t know who made the old map Ovid is following, or where he got it, or what the Old things used their coins for, or why the town is named “Discovery.” But I don’t think we need to know. And in fact, it’s almost better that we don’t know about the town—isn’t it kind of nice that it’s named “Discovery” but we never discover why? Besides, that allows us to focus on Ovid’s discovery there. He finds the place he’s been looking for and the woman he wants to hang out with. Will they have a long-term relationship? Who knows?

Maybe some other hot summer I’ll have a hankering to do some more cussing, and I’ll look in again on Ovid, Ruby, Charley, Jack, and Hugh, and see how they’re all doing.

In case you’re worried: no horses were harmed in this story. Of the countless rounds that were fired through the livery stable, not a single one so much as grazed any of the forty-seven horses in residence.

Finally, I’d like to dedicate this story to my dad. I hope he can read it from where he is, and I wish he were here to discuss it with me. Dad loved horses and taught me how to shoot. Though he never lived west of Illinois, he was a cowboy at heart—out riding the lonesome trails, listening to the coyotes, and watching the big sky.

Challenge! Discovery is now available on Kindle for US$5.00 and will be available in print the first week of November for $11.00. Once the print version appears on Amazon, there will be Kindle MatchBook of $0.99.

Sharing in the Goodreads S&S group. Like Return of the Sword… RBE returns!

https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/1165879-publisher-editor-rogue-blades-entertainment-rbe?comment=172214866#comment_172214866

Good to see this coming over the horizon, Jason! I’ve been waiting for awhile. I’m sure it’ll be worth it.

Ha! I’d forgotten that Fred landed in the top 10 twice. (Frankly, it’s a good thing for the rest of us he didn’t submit ten stories!) I’m so glad you also included his behind-the-scenes essay on writing “Someplace Cool and Dark” — I remember reading that with interest, and I think it’s excellent that you included it in the collection. A nice bonus!