Dune by Frank Herbert

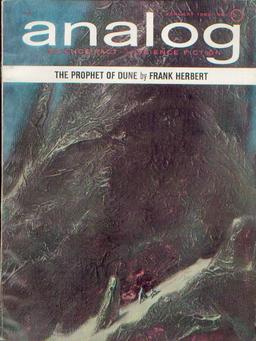

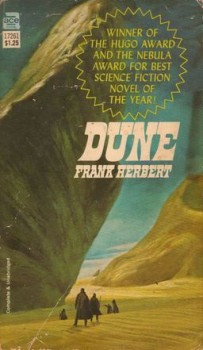

It’s been called the greatest science fiction novel of all time. Maybe, maybe not, but it’s one of the best I’ve ever read. Published all the way back in 1965, it’s the best-selling science fiction novel of all time. The first half of Dune made its debut as “Dune World,” starting in the December 1963 Analog. The second half, “The Prophet of Dune,” began in the January 1965 issue.

It’s been called the greatest science fiction novel of all time. Maybe, maybe not, but it’s one of the best I’ve ever read. Published all the way back in 1965, it’s the best-selling science fiction novel of all time. The first half of Dune made its debut as “Dune World,” starting in the December 1963 Analog. The second half, “The Prophet of Dune,” began in the January 1965 issue.

I read Dune for the first time in 1981, at the age of 14. From the very first pages I was hooked. I was house sitting for my grandfather, and the only things I had to do were let the dog out and feed her and myself, and that meant I barely put the book down all day. Like Dune’s hero, Paul Atreides, I was wondering what the heck is a gom jabbar? Who are the Bene Gesserit? What is melange? My dad’s paperback, at 544 pages, is one of the longest books I’ve read in a single day (beat only by Terry Brooks’ The Sword of Shannara).

I’m not sure what triggered it, but something called out from the depths telling me it was time to reread Dune again. The last time (which was the fourth time) I read it was nearly 20 years ago. A friend wanted to get into science fiction, so a few of us started rereading the classics and tossing them his way. Among the books I revisited were Asimov’s Foundation Trilogy and The Gods Themselves, Clarke’s Rendezvous With Rama, Heinlein’s Orphans of the Sky, and Herbert’s Dune.

Of all those, Dune is the only one I would recommend without hesitation. Foundation is terribly rusted with age, flat prose, and limited characterization. The latter two problems apply to Gods and Rama as well. Orphans is good and pulpy, but ultimately nothing special.

Of all those, Dune is the only one I would recommend without hesitation. Foundation is terribly rusted with age, flat prose, and limited characterization. The latter two problems apply to Gods and Rama as well. Orphans is good and pulpy, but ultimately nothing special.

Dune, on the other hand, is a book that, despite some middle-age quibbles, remains exciting and fresh fifty years after its debut and numerous readings.

For the handful of readers unacquainted with Dune I’ll give a quick synopsis. By dint of charisma and intelligence, Duke Leto Atreides of the planet Caladan has become an impediment to Emperor Shaddam Corrino IV’s accumulation of more power and wealth. Using Atreides’ great enemy, Baron Vladimir Harkonnen as his cat’s paw, the Emperor engineers an intricate plot to wipe out his opponent.

The sole source of melange, or spice, which gives its users mental prescience which in turn allows starships to safely plow the interstellar gulfs, is the planet Arrakis. Supposedly to ensure that the spice will flow, the emperor takes the rule of Arrakis from the brutal Harkonnens and gives it to Duke Leto. Everyone knows that the Harkonnens will not countenance the loss of their greatest source of wealth, and that the transfer of power is a trap.

The great struggle between emperor and feuding noble houses is the backdrop for the real heart of the novel: the rise of Duke Leto’s son, Paul Atreides, as the messiah of Arrakis’ native Fremen, and the possible savior of all humankind.

At the beginning of Dune, Paul is fifteen years old, and has been trained from near-infancy to fight, lead, and rule. His mother, Jessica, Duke Leto’s concubine, is a member of the Bene Gesserit. The Bene Gesserit are a matriarchal order of mental and fighting savants dedicated to creating the Kwisatz Haderach, the genetic messiah capable of seeing into heretofore unviewable regions of the future, and of protecting humanity from its eventual destruction. Though she was ordered to give birth to a daughter in order to further their goals, she deliberately bore a son. Under her guidance, Paul has learned many of the Bene Gesserit mental and physical skills.

At the beginning of Dune, Paul is fifteen years old, and has been trained from near-infancy to fight, lead, and rule. His mother, Jessica, Duke Leto’s concubine, is a member of the Bene Gesserit. The Bene Gesserit are a matriarchal order of mental and fighting savants dedicated to creating the Kwisatz Haderach, the genetic messiah capable of seeing into heretofore unviewable regions of the future, and of protecting humanity from its eventual destruction. Though she was ordered to give birth to a daughter in order to further their goals, she deliberately bore a son. Under her guidance, Paul has learned many of the Bene Gesserit mental and physical skills.

Once on his own, Paul encounters numerous enemies, and a planet where water is worth more than gold and sandworms hundred of meters long. Eventually he faces the dilemma that in order to survive, he might have to become the Fremen’s messiah and lead a savage jihad across the stars.

Rereading Dune has been as enjoyable as it has been fascinating. The book is exciting and packed with wonderfully complex plots and characters, and Arrakis remains one of the most detailed and fully realized sci-fi worlds. I don’t know if Dune is the first environmental sci-fi story, but it’s one of the most potent.

I was also struck, happily, by how much of the book I remembered. From lines like, “Tell me about the waters of your homeworld,” to whole scenes like the revelation of Baron Harkonnen’s plans, the book feels far more familiar to me than I had expected it to. Yes, I’d read it four times before, but it’s been a long time, and I was really surprised.

This reading, though, brought several things to my attention that were previously glossed over. This is the first time I’m coming at Dune with a critic’s eye. The narrative gears are obvious, almost hideously so, at times. Every one of the early chapters is an info dump.

It does make sense, though, as Dune is a complicated book. Herbert, in trying to give readers all the tools to understand things once the plot really gets moving, throws a load of information at you right away. The trick he pulls off so well is how he weaves it into the expanding story. Between each paragraph of plot and characterization, there are one or two of exposition:

- While the Reverend Mother tests for Paul’s humanity with the pain box, she also talks about the Butlerian Jihad and the Kwisatz Haderach.

- Baron Harkonnen’s chapter introduces the spice trade and the emperor’s killer elite, the Sardaukar, and at the same time clues us into how the House Atreides will be betrayed and destroyed.

- Paul’s teachers, Thufir Hawat and Gurney Halleck, reveal plots within plots ensnaring the House Atreides, while also providing an understanding of the political and economic systems of the Dune universe.

Each of the early chapters does the same thing, and it stands to Herbert’s talent that it feels natural even when it’s so obvious.

I’m older and wiser now, and the great theme of Dune is much more apparent and clear. In 1979, Frank Herbert said:

“The bottom line of the Dune trilogy is: beware of heroes. Much better rely on your own judgment, and your own mistakes.”

In a book replete with moving deaths and sacrifices, I found the most heartbreaking line to be:

In that instant, Paul saw how Stilgar had been transformed from the Fremen naib to a creature of the Lisan al-Gaib, a receptacle for awe and obedience. It was lessening of the man, and Paul felt the ghost-wind of the jihad in it.

I have seen a friend become a worshipper, he thought.

One of the few significant failings in Dune is Herbert’s limited display of how and why the Fremen come to truly believe in Paul. Oh, there are prophecies he seems to fulfill and deeds he succeeds at, but there is never a debate among only Fremen about following Paul. When he comes up against certain traditions of the Fremen that thwart his plans, and he declares them abolished, there is no great outcry, only acceptance. Even though much of the book is told through its characters’ thoughts, we never hear from any of the Fremen more than initial trepidation, quickly replaced with acknowledgment of Paul’s true nature as a prophet.

Herbert knows humans crave a savior, capable of leading them to some perfect world, where all hardship and troubles have been swept away. The Bene Gesserit have been breeding the members of the Great Houses for thousands of years to force one into existence. The Fremen, exiled across the galaxy for untold ages before reaching Arakkis, have long hoped for one’s coming, and when he seems to arrive, they are ready to place all their trust and faith in him. Only Paul fears what it means to be a messiah and what it will do to the Fremen, their world, and the galaxy. Only by great dexterity, and with fully-realized characters and setting, was Herbert able to make this exploration relatable as well as believable, but he did.

“To hold Arrakis,” the Duke said, “one is faced with decisions that may cost one his self-respect.” He pointed out the window to the Atreides green and black banner hanging limply from a staff at the edge of the landing field. “That honorable banner could come to mean many evil things.”

The Duke took an antifatigue tablet from a pocket, gulped it dry, “Power and fear,” he said. “The tools of statecraft. I must order new emphasis on guerrilla training for you. That filmclip there — they call you ‘Mahdi’ — ‘Lisan al-Gaib’ — as a last resort you might capitalize on that.”

Paul stared at his father, watching the shoulders straighten as the tablet did its work, but remembering the words of fear and doubt.

When I read the book at fourteen, I was swept up into the depths of Herbert’s creation and Paul’s voyage from young ducal heir to world-freeing messiah. There’s a power fantasy element to Dune that was irresistible to my adolescent self. Presented as swashbuckling space opera only made it more compelling. As I’ve aged along with the book, I’ve come to see and appreciate it for more than just its story.

At some point the ecological elements took on greater salience for me. Dune is no green manifesto, but it does contain a call to understand the natural environment. The Fremen intend to change Arrakis into an Eden, but doing so demands a complete understanding of the planet’s ecosystem, a point Herbert drives home many times:

“The thing the ecologically illiterate don’t realize about an ecosystem,” Kynes said, “is that it’s a system. A system! A system maintains a certain fluid stability that can be destroyed by a misstep in just one niche. A system has order, a flowing from point to point. If something dams that flow, order collapses. The untrained might miss that collapse until it was too late. That’s why the highest function of ecology is the understanding of consequences.”

The loss of human autonomy — another of Dune’s great themes — caught my attention more than anything else during this reading. Herbert looks at

the desire to give up freedom in exchange for a deliverer, and to hold on to it by shunning machines capable of supplanting human decision-making. In an era when we give over many of our choices to what algorithms pick for us, and politicians routinely present themselves as the answers to all our problems, these concerns felt especially important.

Dune just might really be the greatest science fiction book of all time. It tells a ripping story and takes up important matters that it then addresses in approachable ways. When you’re done, you will swear you can smell spice in the air around you, hear the giant sandworms rumbling under the the earth, and hear the low static-like buzz of body shields. The sounds of great battles, roaring armies, and clashing swords will echo in your mind for days after you’re done. And you will also be thinking about what it means to be human.

In his review of Dune, Anthony Burgess regretted that Herbert had done such great work for a “mere fantasy.” The obvious thing, though, about a fictional story is that, sometimes, it’s a better way to look at the world than through a work of non-fiction. Rereading Dune, it is very clear this is no “mere fantasy,” but rather it is a great and important work of art. If you’ve read it, maybe it’s time to pull it back off your shelf. If you haven’t, this is definitely a book to read at your first chance.

From the very beginning, Dune has been an inspiration for artists of all types. For some of the art of Dune, I’ve collected a batch at my site, Stuff I Like. For the musically inclined, you can follow the link to hear Iron Maiden’s 1983 track, “To Tame a Land.” There is also a movie from 1984 I’d prefer to imagine doesn’t exist and miniseries from 2000 I’d like to believe is far better than it really is.

Note: Herbert wrote two initial sequels, Dune Messiah (1969) and Children of Dune (1976). I’ve read both and I remember them being fair to good. Both are short and concise. Later, he wrote three more sequels, God Emperor of Dune (1981), Heretics of Dune (1984), and Chapterhouse: Dune (1985). I have never read any of them, and the little I’ve heard of them isn’t good. Just in case they’re good, I have copies of all of them, along with the Dune Encylopedia, the work of lovingly obsessive fans.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him. Right now he’s contemplating reading Swords & Sorcery again.

A day ? You read it in a day ? I don’t know if I’m appalled or impressed. I’ll go with shocked. A day ?

I’ll speak heresy and say that I’ve never really liked it. I recognize it as a landmark achievement in worldbuilding, but there’s something about Herbert’s style that, on a sentence by sentence level, makes him very difficult for me to read with any pleasure. I had the same experience with Dune that I had with Under Pressure: I would finish a paragraph or two and realize that I had no idea what had been said. Likely the problem lies more with me that with Herbert, but there it is.

I would actually go so far as to say this is not just the greatest science fiction novel ever, but due to its complexities and intricacies I would tend to call it the greatest novel of all-time. Definitely one I reread about once a year. Incidently, I also reread Sword of Shannara about once a year and had been thinking of rereading that soon.

Although I never read Dune in a single day, there were 2 even longer books I did read in a single day. When Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix came out I was working an overnight shift, so I used a vacation day, did the midnight release party thing, and finished reading it about 8:00am, right around the time I normally went to bed back then. Later, when A Memory of Light (the final Wheel of Time book) came out, I was unemployed so not only did I read it the first time in a single day but the following day I reread the whole thing. Although in the case of that particular book it was definitely too fast. When I was doing a complete Wheel of Time reread last year I realized how little I remembered of it.

Amy – I have learned to skim read because ‘I wanna know’ but I cant bear a word by word read. And I can relate to a reread where I remember little of it. But I get so much more out of it the second time ! I dunno if Dune is the best SF and/or novel ever but I do love it.

I found myself suggesting “Dune” to some friends while discussing the problem of radicalization. The novel can (also) be read as a handbook on how faith can be hijacked to further the political agenda of a group or individual.

Maybe because of this, much as I like the book, I always found Paul Atreides slightly disquieting.

Dune is definitely emerging from the science fiction of its day (early 1960s), but it was such a step up in scope and complexity that it felt like something really new, at that time. It came at a time when the upheaval of the 1960s was seriously gearing up–a popular President had just been assassinated, this new group called The Beatles were suddenly everywhere on the radio, all the complacency left over from the 1950s had gone out the window.

Now I believe Dune is underrated, especially by the younger readers and those who prefer their SF “literary”–like, why would read this pulp when you could be re-reading “The Road” or whatever the latest eastern European surrealist novel is? I still find it well written in the old-fashioned adventure story way (where there is rising action and characters aren’t totally lacking in affect). In spite of the giant worms and harsh deserts, much of Dune could be taking place on a stage set, and you can think of Herbert writing chapters as acts in a stage drama. (Under Pressure and Destination Void could easily be plays.) No one matches him in being able to switch points of view without losing the reader to allow a mingling of dialog and different interior monologs, almost a Strange Interlude in space.

The novel does have faults, especially when modern sensibilities are taken into account. Herbert adopts the lazy shorthand of his time to emphasize a character’s evil by using physical characteristics and sexual practices. So the Baron is a pederast and most likely has abused his nephew, plus he’s old and immensely fat. This is the type of overloading of signifiers that was common at one time and still shows up in a some YA. Also, Herbert is always engaging with the worst of Darwinian theory mis-applied to society, where the oppressed population in the harshest environment will produce the kind of ruthless killers to overrun and destroy the “soft” civilized societies. This comes up again and again in his writings (The Dosadi Experiment and Hellstrom’s Hive, for example).

But Dune was the first SF work to look at the intersection of religion and politics and ecology in a somewhat thoughtful way while still telling a good yarn. I think it will still be read when many of the other novels by Herbert’s more highly regarded contemporaries (Blish, Simak, Bester, even Sturgeon and Aldiss) will be forgotten.

Over on Tor.com, Emily Asher-Perrin has been doing a re-read of the Dune books (http://www.tor.com/series/rereading-frank-herberts-dune/), up through the last one Herbert wrote, Chapterhouse: Dune.

She has finished Dune, along with both of its adaptations (Lynch movie, Syfy mini-series) and one near-miss (Jodorowsky’s movie), and is through Dune Messiah and almost finished with Children of Dune.

@Barsoomia – yep, a day. There’s little like the monomania of a nerdy 14-year old with no obligation beyond getting to the end of a book.

@Amy B. – Wow, wow, I say, that’s an insane amount of reading. By the time the Harry Potter books rolled around I rarely had the ability to knuckle down like that and read 800 pages in a day.

@Davide – And well you should find Paul disquieting. Have you read either of the immediate sequels? That’s clearly what Herbert was aiming for.

@cpheron – Definitely a leap forward in complexity and density for sci-fi at the time, and I really agree that the younguns are missing out on something grand if they skip Dune.

Yeah, Herbert took some shortcuts with his depiction of the Baron and his family. I’d argue thought, it’s a way to highlight the greatest drawback to hereditary rules: roll well and you get Duke Leto, poorly and you end up with Duke Vladimir.

@Eugene R. – Thanks for the heads up, I’ll go take a look.

[…] Fiction (Black Gate) Dune by Frank Herbert — “Herbert knows humans crave a savior, capable of leading them to some perfect world, […]

I read it in 24hrs the first time around. I reread it a couple years ago. Herbert also tackles the “barbarism vs civilization”/”virility vs decadence” theme as well. We don’t know if Frank was a fan of REH, but his friends Poul Anderson and Jack Vance were. Overall, it’s not perfect…but it’s the best SF novel ever written.

[…] Fiction (Black Gate) Dune by Frank Herbert — “Herbert knows humans crave a savior, capable of leading them to some perfect world, […]

Fletcher: great work here. It is hard to know which of the old warhorses will survive, or should survive, among readers of a new generation. Dune a good candidate, though cpheron makes some good points. The book is a critique of heroism, but also a heroic melodrama, and sometimes you can hear the corn popping.

Re predecessors:

@cpheron: “But Dune was the first SF work to look at the intersection of religion and politics and ecology in a somewhat thoughtful way while still telling a good yarn.”

It’s a very good one, but not the first. Blish’s A Case of Conscience and Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land had paved the way. It was steam-engine time for this stuff in the late-50s-to-mid-60s.

Re Dune‘s bestness: de gustibus non disputandum. I guess I’d still rate Le Guin’s Left Hand of Darkness above Dune or all others. Le Guin tells a clearer, starker story, with something to say about what it means to be alive. But I can see why someone might prefer Dune Fortunately, we have both and don’t have to choose.

@Deuce – Yeah, it’s that kind of a book. As to the barbarism v. civilization debate, there’s clearly an element of that in there – though the Fremen are making every effort to educate and modernize themselves.

@James E. Thanks! Finding that Herbert quote warning about heroes provided a nice hook to hang the article on. And, sure, there’s some hard-to-avoid corniness, but I agree Dune’s one of the “classics” that will probably survive.