The Man of Legends by Kenneth Johnson: Q&A with the Author, Part 2

Kenneth Johnson’s new book, The Man of Legends is now available at Amazon in paperback, Kindle, and audiobook.

Kenneth Johnson’s new book, The Man of Legends is now available at Amazon in paperback, Kindle, and audiobook.

Last week I posted the first part of my interview with Kenneth Johnson, author of the recently released novel The Man of Legends, focusing on the new book and its inspirations. But Kenneth Johnson’s long career as a writer, producer, and director of television and movies deserves its own section. Shows like The Incredible Hulk, Alien Nation, The Bionic Woman, and V: The Original Series are gems among 1970s and ‘80s science-fiction television and continue to have an enormous influence today. I expected to hear some interesting stories about making those programs when I interviewed him, especially considering how timely some of them continue to be (seriously, go give V: The Original Miniseries as look again and you’ll be stunned at how much its themes stand out), but I didn’t expect to hear a story about Richard Nixon as well!

Q&A with Kenneth Johnson, Part 2

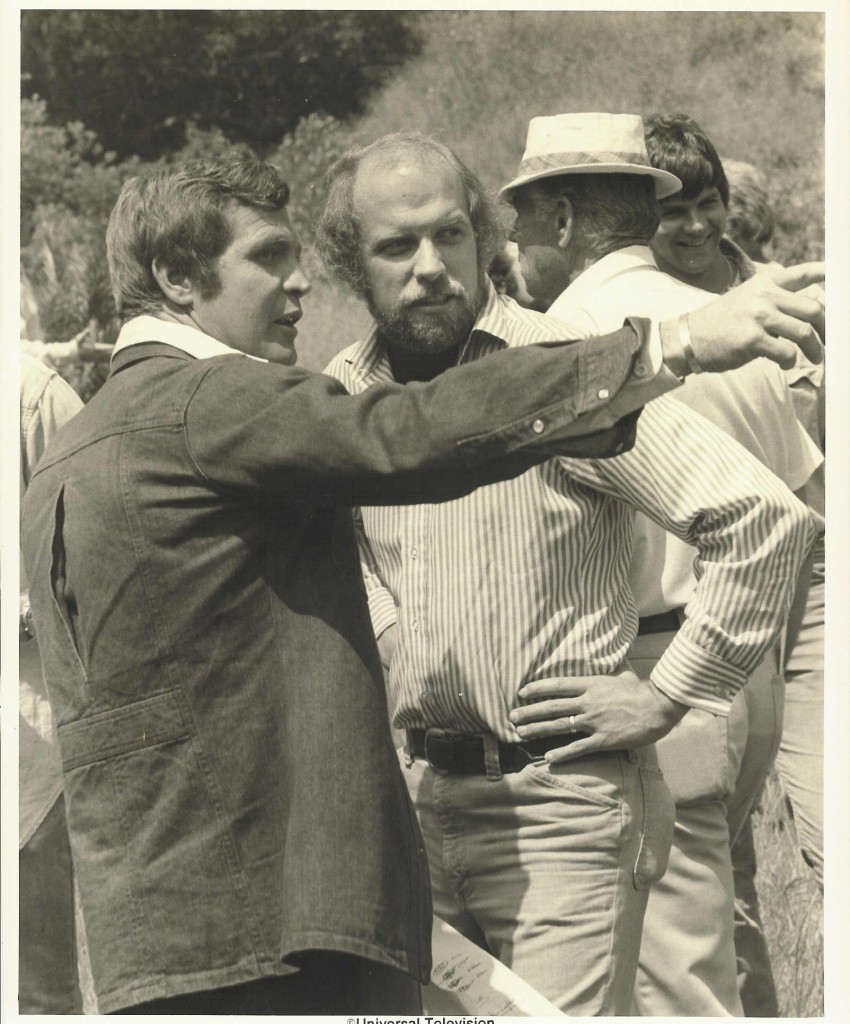

You mentioned you were one of the youngest producers on the lot when you were working at Universal. You were in your early thirties when you produced The Six Million Dollar Man, The Bionic Woman, and The Incredible Hulk.

Yeah, and I had had half a career before that. I came out of the Drama Department at what is now Carnegie Mellon University, then Carnegie Tech, which had a sort of renowned Department of Drama. I was a graduate in directing; there was no film or TV or anything like that. It was strictly “theater!” you know. Everybody there, except me, sort of looked down on TV and film. Everybody except me and a couple other guys: Jamie Cromwell, a wonderful and well-known actor out here who played the farmer in Babe and so many other things since then; and my dear friend Steven Bochco, who was a classmate and came to California a little bit ahead of me and helped me get my foot in the door at Universal.

Before that I was producing and directing TV in New York for a couple of years based on a film I had actually managed to make while I was at college — even though there was no film equipment! It was challenging, but we made it. In 1966 I was asked to become a producer on The Mike Douglas Show, which was before your time. It was the first ninety-minute daytime talk show. I worked on it briefly as an intern while still in college. Westinghouse asked if I would join The Mike Douglas Show as producer. You know how popular Oprah has been, of course. The Mike Douglas Show’s audience was ten times the size of Oprah’s. Sixty or seventy million people a week. It was an amazing place to work. But — I didn’t want to to do that. I wanted to make movies in Hollywood. But they asked me to meet the young guy who was taking over as executive producer. So I went to meet … Roger Ailes.

Whoa.

Yeah. And Roger was incredible. Really fascinating, brilliant, funny guy. Incredibly seductive. I said, “Roger, I don’t want to do ninety minutes live a day six times a week.” And he said, “I’ll let you do a lot of film.” And so he sucked me in and we worked together for a good solid year. Then — it’s funny, in light of the later things that happened in Roger’s life, which I was not privy to at all, the only person I ever saw Roger hit on was Richard Nixon. That happened in 1968 when Nixon was doing the show. Roger grabbed him and said, “Mr. Nixon, you can hire me because I can get you elected president.” Nixon said, “How can you do that, Roger?” He said, “You need a media advisor.” “What’s a media advisor, Roger?” “I am. I just created the title.” So Roger left to produce Nixon and I took over as the executive producer of The Mike Douglas Show. And I was — twenty-five years old! I was there for another year-and-a-half after that.

I finally said, “I’ve really got to go to Hollywood.” And I said, “Here I am, Hollywood, ready to make movies!” And they said, “No, you’re a talk show producer.” I realized I sort of had to start all over again. Stephen Bochco was tremendously helpful in all that because he convinced me — because I was primarily a director at that point — “You know Kenny, if you can write, you can get your foot in the door more easily.” And I said, “But writing’s hard. I don’t want to do that.” And Steve said, “No, it’s not hard. You just have to stare at a blank sheet of paper until beads of blood appear on your forehead.” For me, that’s what it was like. But he insisted and pressed, and so I took a stab at it and discovered that I could write pretty fast and with a certain degree of quality. I became a great writer of unproduced screenplays. Most of them are still on my shelf.

I finally said, “I’ve really got to go to Hollywood.” And I said, “Here I am, Hollywood, ready to make movies!” And they said, “No, you’re a talk show producer.” I realized I sort of had to start all over again. Stephen Bochco was tremendously helpful in all that because he convinced me — because I was primarily a director at that point — “You know Kenny, if you can write, you can get your foot in the door more easily.” And I said, “But writing’s hard. I don’t want to do that.” And Steve said, “No, it’s not hard. You just have to stare at a blank sheet of paper until beads of blood appear on your forehead.” For me, that’s what it was like. But he insisted and pressed, and so I took a stab at it and discovered that I could write pretty fast and with a certain degree of quality. I became a great writer of unproduced screenplays. Most of them are still on my shelf.

I’ve got a few of those too!

I’m sure! But one of them Steve passed along to a guy named Harve Bennett [later producer of the Star Trek movies, including Wrath of Khan] who was doing The Six Million Dollar Man. Harve really liked it and liked the writing. He couldn’t help me get the movie produced, but he asked me to come up with some ideas for the show. That’s where the character of the Bionic Woman came from. Then Harve invited me to join Six Million Dollar Man as producer, so for a while I was producing The Six Million Dollar Man, and Bionic Woman spun off into its own series and … agh, doing one episodic television show is like living in a garbage disposal, but doing two didn’t give me any time to direct. So I finally let go of Six Million Dollar Man and just stayed with Bionic Woman.

I recently watched an interview with writer Steven E. de Souza, and he talked about how difficult it was to find writers for Six Million Dollar Man because the procedural writers didn’t know enough about SF, and SF writers didn’t know the crime procedural stuff.

It was more than that. With The Bionic Woman I was more interested in digging deeply into character and into relationships. I was not so interested in missions and “Steve, you gotta go in there, pal, and get the icon from the gods,” and “Okay, Oscar!” The theatrical training that I had at Carnegie was all Stanislavski-based, it was all based on building characters and building relationships and the emotional structure. Harve actually educated me on how I could blend that more substantive stuff with the kind of pop culture that we were doing. I realized that there was a way to do that, and The Bionic Woman came out of that.

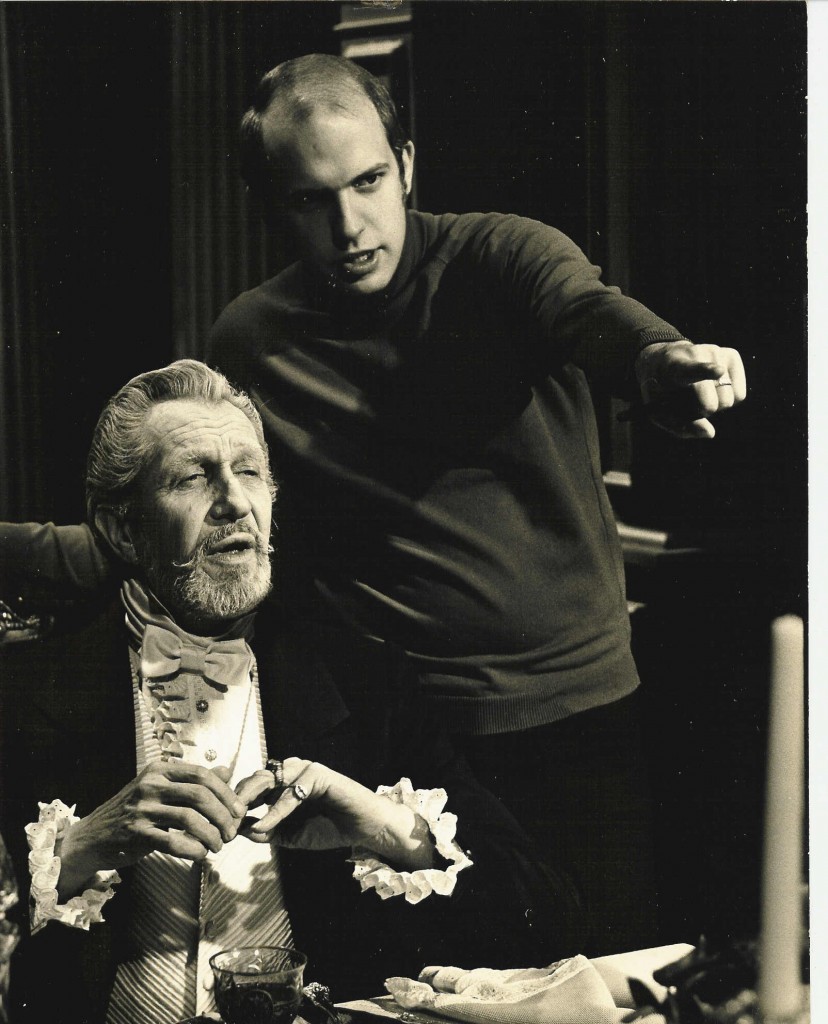

I got more deeply into it when I was doing The Incredible Hulk. Because … well, after being a talk show producer, and then you come out to Hollywood and you create The Bionic Woman and produce The Six Million Dollar Man, suddenly you’re the science-fiction guy. Frank Price, who was running Universal, told me they had acquired the rights to several of the Marvel Comics superheroes, and which one would I like to do? And I said, “Eh, none of them, thanks.” But I was reading Les Misérables at the time, and I had Jean Valjean and Javert and the fugitive concept in my head. I realized if I could take that and a little Robert Louis Stevenson Jekyll-and-Hyde kind of stuff and this ludicrous thing called The Incredible Hulk, I could really turn it into a drama that was adult-based. It was not a “comic book” piece. That’s what I set out to do, and I think we did it pretty successfully. I was really pleased with that.

It’s interesting: my audience has always been — demographics is what the studios and networks are always looking at, meaning “How does the audience break down?” — and my demographics were always what they considered ideal, because my largest audience was always adult women. Then men, then teens, and then kids. Which is really unusual for science fiction. This carries through from the Bionic shows, to The Hulk, to V, to Alien Nation, to everything I’ve done in that genre. My largest audience has always been women. I think it’s because of exactly that same thing: that I was more interested in character relationships and the emotional quality than the surface-y kind of stuff.

In my first script for V, as you may know, there were no aliens or spaceships in it. It was a grassroots fascist uprising.

In my first script for V, as you may know, there were no aliens or spaceships in it. It was a grassroots fascist uprising.

You based it on It Can’t Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis, as I recall reading.

Exactly. It Can’t Happen Here. Not that it couldn’t nowadays — goodness gracious! Oh, don’t get me started. I’m under oath here!

I rewatched the miniseries last week. It’s upsettingly relevant.

[Laughs.] I know! You know what it is, it’s a timeless story, which is one of the great beauties of V. I discovered a couple of years ago that I own the motion picture rights. Warners owns the TV rights because I was under contract when I did that with them. They have tried to revive V a couple of times, not very successfully. But I own the motion picture rights. And suddenly, I had a lot of new best friends, you know. All the major studios — literally, all of the major studios — came at me from the highest echelons and wanted to pay me an obscene amount of money to buy the rights to let me produce, maybe let me write. But for director they were thinking maybe somebody like Michael Bay. And I’m saying … no.

In Hollywood, though, as you may know, when you say “no” they usually go, “Okay, okay, we understand. How much money do you really want?” And I said, “No, it’s not that. I want to protect my baby.” So we’re endeavoring now to set up V as an independent motion picture, the first of a trilogy. The last two sequels would be based on my later novel, V: The Second Generation. It’s an uphill battle, because for an independent picture that costs $60 million it’s been challenging. We’ve been close a number of times, and we still are again.

But part of what’s driving us is exactly what you said: the story is more timely than it has ever been, including the impact of the media on our society. Of course, there was no Facebook, no Internet, no cell phones and all of that when I did the original V. But V is really Spartacus and the revolt of the slaves. It’s like any oppressed people who are under the thumb of some power and how people react. That was the story I wanted to tell.

The original screenplay was going to be a movie. There were no aliens or spaceships or anything like that in it. Brandon [Tartikoff], when he read the script, which I just let him read as a friend because I wasn’t interested in doing it as television, he said, “This could be a great big miniseries, and go beyond that and have life as a series.” But he didn’t know if Americans would really “get” fascism. I tried to convince him that it was not a complicated project: you shave your head and put on a black shirt and beat somebody up. He was hoping it could be an outside source like the Soviets or the Chinese. I didn’t buy it. And one of the guys at the back of the room said, “How about aliens?” And I thought, Oh God, don’t go there! — because of all the science fiction I’d already done.

But the more I thought about it, the more I realized, “Whoa, wait a minute. That’s not a bad idea.” I can tell the story I want to tell, which is a story about power and how people respond to it. When a hyper-power rolls into your life, some people will be like the Vichy French and suck up to the Nazis in order to aggrandize and enrich themselves. Others will say, “I’ll go along to get along and keep my head down, hoping they won’t bother me.” And then the third group are the ones who become the heroes — the resistance — and they fight back and say, “No, this is a mistake and this power is being abused.” And it’s for that reason that we’ve been so eagerly pursuing getting a new movie made.

The other thing is the staying power that V has had. When we went on the air it was the number one show in the country. Eighty million people tuned in, it had a 40 share [the percentage of households watching the show], it was humongous.

No show would get a 40 share today, ever!

I know, no kidding! And the reviews: it was critically acclaimed. It was just amazing. And the one person who wasn’t happy with it was me — because I hadn’t been able to make it look the way I wanted, the way I saw it in my head. And now I can, and we’re endeavoring to do that.

Interestingly, V became and still is — and probably always will be — the highest-rated work of science fiction in the history of television.

The reason you have studios coming to you today is because those executives at the studio are my age, and they watched V: The Original Miniseries when they were ten years old. At that age we didn’t notice the budgetary limitations much. Watching it today I notice things I didn’t back then, such as: “That’s not a hole in the road, that’s concrete piled around in a circle to make it look like a hole.”

The reason you have studios coming to you today is because those executives at the studio are my age, and they watched V: The Original Miniseries when they were ten years old. At that age we didn’t notice the budgetary limitations much. Watching it today I notice things I didn’t back then, such as: “That’s not a hole in the road, that’s concrete piled around in a circle to make it look like a hole.”

[Laughs] Of course, when we were filming in Monrovia! At the time I made it, V was the most expensive miniseries that have ever been made. And yet — we didn’t have the kind of money that I needed; we didn’t have the time in order to do adequate prep. Normally for a four-hour miniseries you have four months of prep. From the day Brandon read my script and said “go” to the day I said “action” was two-and-half weeks. People in the industry hear that and go, “Wha—? No, that’s impossible.” And I say, “Yeah, well, guess again. We did it.”

But in spite of the critical acclaim and the audience reaction, not only in North America but around the world, I wasn’t happy with it. And it was frustrating for me because I didn’t have the tools to do it well. There are visual effects in V that cost seventy or eighty thousand dollars for twenty seconds of film, and you could do it on your cell phone today and it would look better than what I did then. So that’s the exciting thing about trying to set it up as a movie. So if you know anybody … hey, I’d love to get the whole $60 million in one check, but I wouldn’t complain if we could line up ten or twenty, so…

People tend to assume that someone who’s been successful for a long time in their career automatically has the clout to get anything made. But some of the most successful filmmakers in Hollywood are struggling to get projects greenlit.

You know, it’s funny because of what you said about so many of the studio heads now being the age you were when I originally did V. Part of the problem is so many of them only remember their twelve- or fourteen-year-old perspective on it, which is all action and adventure.

The laser guns and spaceship dogfights.

Right. And they didn’t get what made it so successful was the depth and the substance. The very first rough cut that I saw in a screening room at Warner Bros. — which we did with four different editors because we were working so fast — didn’t have any visual effects or any of that, there was no music, there were so sound effects. It was just the performance, just the actors — and it took your head off because the drama was so, so good. And that’s why so many audience members in the adult range embraced it so thoroughly. All the rest was just bells and whistles.

When The Incredible Hulk started to stream on Netflix a few years ago, I plunged right into it, and think I enjoyed it more than I ever had.

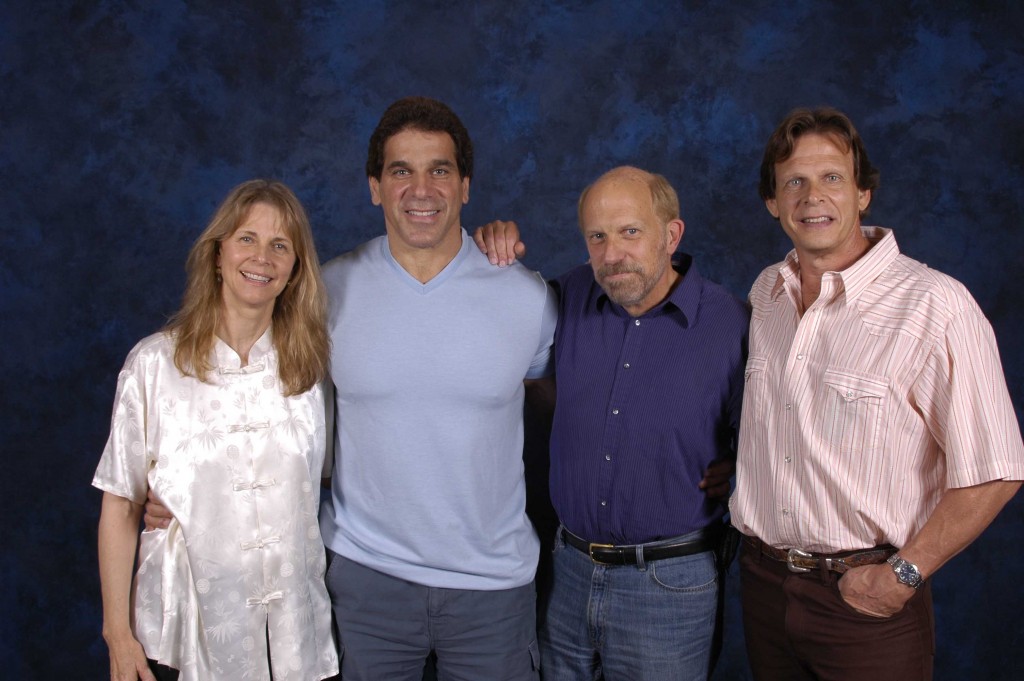

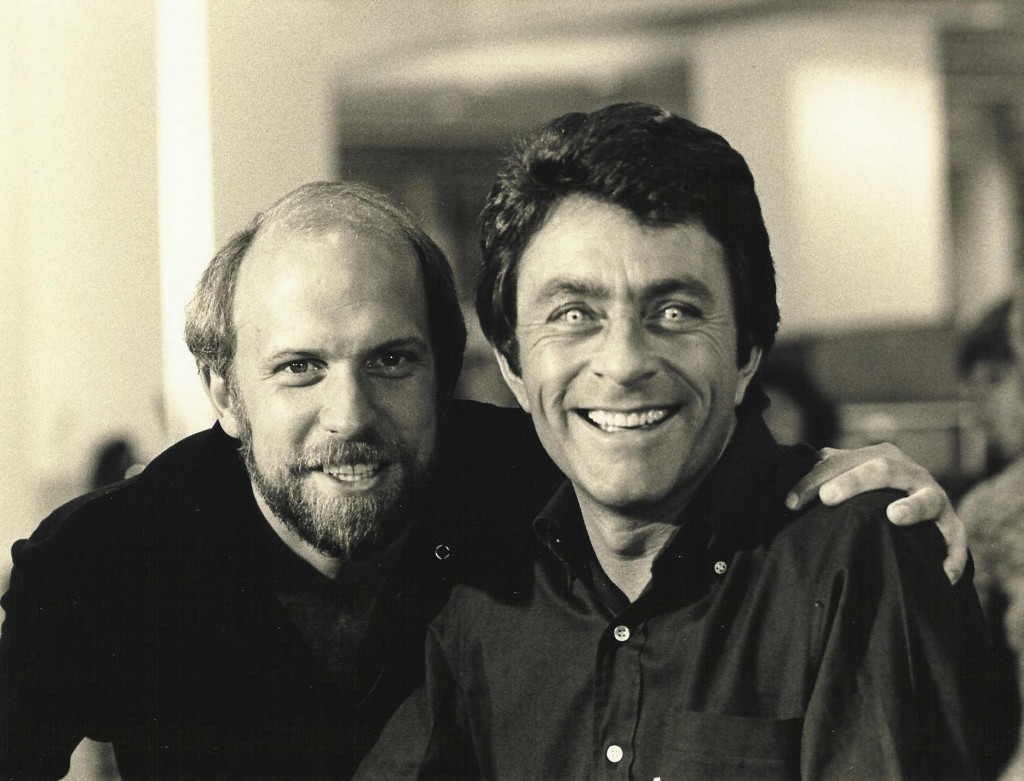

It’s amazing how many of the episodes still hold up. Bill’s performance was so amazing. It was astonishing to have been so lucky to have created several iconic projects in my life.

A specific question for Incredible Hulk fans: Do you have any thoughts on the 2008 Incredible Hulk film? They borrowed extensively from the television show.

A specific question for Incredible Hulk fans: Do you have any thoughts on the 2008 Incredible Hulk film? They borrowed extensively from the television show.

That was the second one, right?

Yes, the one with Edward Norton.

Quick funny story: I was at the premiere of the first one, which was such a disaster. The only line that got a rise out of the audience was, “Don’t make me angry…” And here’s Ang Lee, brilliant director, I mean Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Brokeback Mountain, great stuff. But boy … at the end of the premiere when the lights came up and everyone was trying to sneak out the back door because the movie was so awful, one of the guys from Variety grabbed me and said, “Mr. Johnson, don’t make me Ang Lee. You wouldn’t like me when I’m Ang Lee.” And I thought, “Oh my god, is that perfect.” The movie tanked. It opened big on its first weekend, then tanked — because it was a bad movie.

When I watched it, I thought, “There’s some nice Hulk action here, but I’m bored with a movie that doesn’t seem to like its actual concept and avoids it whenever possible.”

Exactly. When I saw that Edward Norton was going to be involved in the second one, whom I have a great respect for — and is also a pretty good writer as well an actor — I thought they might be able to do it. And when I saw the trailers come up for the second one, for about the first thirty or forty seconds I thought, “You know, they might just have captured it here.” They went back and rebuilt things to look exactly like my sets! Maybe they’re going to make it work. But then the big green CGI hand comes up through the concrete, and you go [buzzer noise].

You know what it is to me, it’s very simple: you wouldn’t put a real human being into a Shrek movie, and that’s the disconnect it has for me. I think that Joss Whedon did probably the best job with the first Avengers movie, first of all because he underused the Hulk, he didn’t have to carry the picture. Also, Mark Ruffalo was able to contribute to the portrayal in the CGI version.

Ruffalo felt a lot more like Bill Bixby to me.

Yes, it’s true. Ed Norton at Comic Con, when they were about to premiere the second Hulk movie, said they had really tried to go back to the humanity that was involved in the show. He said some nice things about me personally, which was very kind. But — it’s really hard to blend a big green CGI character into the real world. I don’t know … enough said.

I’ve enjoyed what Marvel’s done with the Hulk recently, but you’re right that it’s a difficult character to make the center of a story. If your main character does not want to be the Hulk, you’re in a difficult situation. But the TV show works within the limitations of ‘70s episodic television almost ideally to be able to tell the story as a weekly series. I know that Stan Lee has always said, “They made choices that were different from the comic books, but every choice was the right choice.”

I’ve enjoyed what Marvel’s done with the Hulk recently, but you’re right that it’s a difficult character to make the center of a story. If your main character does not want to be the Hulk, you’re in a difficult situation. But the TV show works within the limitations of ‘70s episodic television almost ideally to be able to tell the story as a weekly series. I know that Stan Lee has always said, “They made choices that were different from the comic books, but every choice was the right choice.”

Bless his heart, Stan was a champion from the beginning. He let me run with it and has had such nice things to say over the years.

I’ll tell you one more funny story. There were many times with Louie Ferrigno would say, [Brooklyn accent] “Kenny, why doesn’t the Incredible Hulk have more dialogue?” And I said, “Well, Louie, for starters, he didn’t come from Brooklyn!” But Louie really grew as an actor, too. One of the parts that I recall were most intriguing to me were when the Hulk was coming down from his “mad” and he was that childlike creature. It was fun for us to explore those sides to him. And Louie got to be very sensitive.

Those were good moments. I began to notice those more as an adult. As a kid you’re hanging on for the “Hulk outs.” As a child you attach to it because you wish you could do that to bullies.

Everybody feels that way. That’s what I started with, that feeling. I think that’s one of the reasons it was so successful because there’s this visceral feeling. The original pilot starts with that title card which says, “Within each of us, ofttimes, there dwells a mighty and raging fury.” We’ve — all — felt — that. We’ve all wanted to “Hulk out” at one time or another.

It puts David Banner in the fascinating position where he wants to help people as much as he can, and ironically one of the ways he can end up helping is the last way he ever wants to help.

When you back away from it and look at it from a broader perspective, which you obviously have, it’s classic Greek tragedy. It’s the hubris of the protagonist thinking they can tamper with things Better Left to the Gods, and the gods say, “Uh uh.”

An emotional connection for me is what I call “The Philip Marlowe Syndrome”: You can help, you can make a difference, you can change things … and you’re still going to be alone at the end. As I child I sometimes wanted to shut the TV off two minutes before the end of an episode because there was this sad music — Joe Harnell’s “The Lonely Man” — and the sight of David Banner walking down a road and starting to hitchhike again. When you’re an adult, you start to understand, “I know what that feels like.”

That’s true, and that’s exactly the feeling I wanted. In those days, every Universal show ended with a big brass band kind of sound. And I said, “Joe, no, it’s gotta be a solo piano.” I can’t tell you how many people I’ve met over the years who tell me they wish they’d been able to drive by and pick up Bill Bixby. The thing that’s even more wonderful to hear, Ryan: hundreds of people have written to me about how they decided to become physicians because of David Banner being a doctor.

He’s the physician as hero. Every time you watch the show, you think, “David, you could just walk on by this.” But he doesn’t. He has to help.

There’s a moment — there’s even a little Hulk in it — where Will in The Man of Legends comes across that burning tenement and turns his back on it and says, “No, I’m not going to do it.” And then he can’t not do it. And that infuriates him so that he’s smashing on the hood of a car, just like the Hulk did.

Thank you to Kenneth Johnson for taking the time to talk to Black Gate!

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

Terrific interview, Ryan. Your love for the various shows really comes through, although I’m surprised you didn’t discuss Alien Nation at all (I think it might have been mentioned a tiny bit in part one).

Wow! Great interview! I loved V as a kid. Incredible Hulk scared me a bit, so I didn’t watch it that much. But I think I was more scared of Bill Bixby with those crazy contact lenses than Hulk.

@Amy – Yeah, we only touched on it once. Unfortunately, even though we talked for an hour and half, there was so much more we could’ve touched on. We just… ran out of time.