The Man of Legends by Kenneth Johnson: Q&A with the Author, Part 1

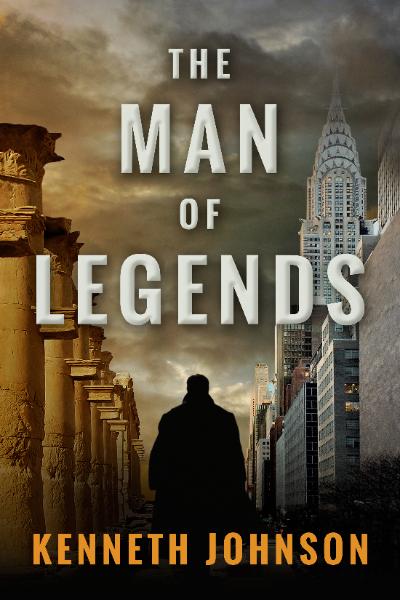

The Man of Legends is now available at Amazon in paperback, Kindle, and audiobook.

The Man of Legends is now available at Amazon in paperback, Kindle, and audiobook.

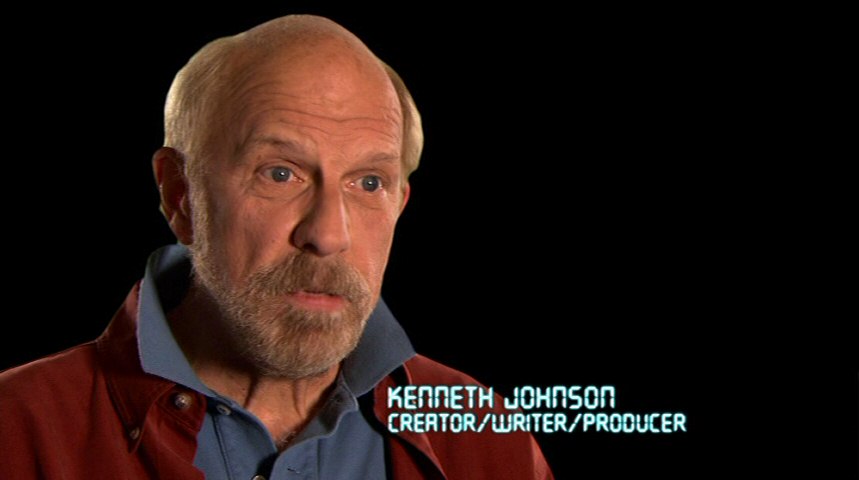

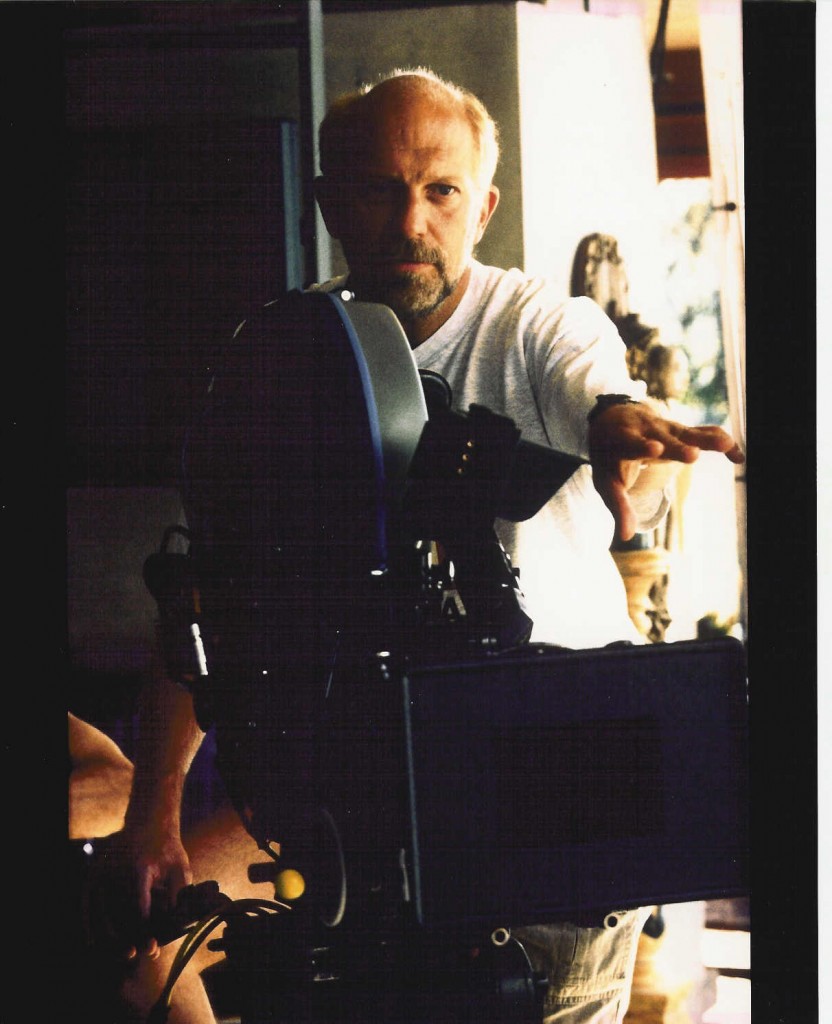

The title of the novel The Man of Legends refers to its central character and one of its numerous narrators: an enigmatic figure with a history stretching back to the ancient world. But the title can also apply to the book’s author, Kenneth Johnson. Although not as much a household word as Gene Roddenberry or Rod Serling, Johnson has left an indelible mark on a generation who grew up watching the shows he produced, developed, wrote, and directed: The Six Million Dollar Man, The Bionic Woman, The Incredible Hulk, V: The Original Miniseries, Alien Nation…

Basically, for people of my generation, Kenneth Johnson was our secret Gene Roddenberry, our hidden-in-plain-sight Rod Serling.

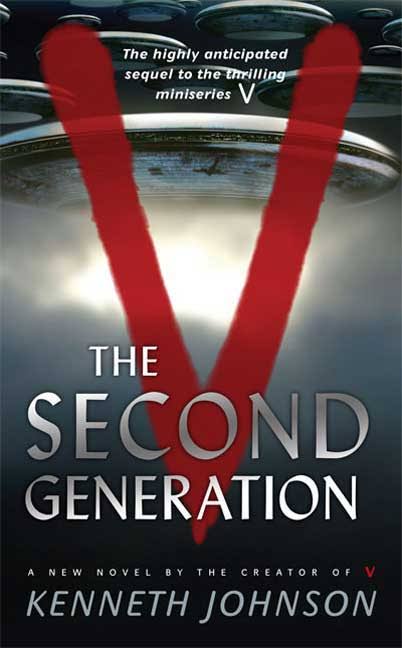

The Man of Legends feels like a declaration that Johnson’s legacy is no longer secret or hiding. Although he’s published novels before (most recently V: The Second Generation, a 2008 continuation of the 1983 miniseries), The Man of Legends is an original story that reads as a collation of the humanism in Johnson’s television and movie work. If a story about a cursed man forced to wander the world, helping people along the way even if it backfires on him, instantly calls up Bill Bixby as David Banner in The Incredible Hulk television show, it’s no coincidence. Johnson even tucks in a few direct references to the TV series. (“Don’t make me angry. You wouldn’t like me when I’m angry.”)

But The Man of Legends isn’t a retread. It’s a summation and expansion. This is unmistakably the work of the author who brought emotional power to David Banner’s lonely quest to be the best person he could while coping with an unconquerable rage and a relentless pursuer. But it’s also unmistakably the work of the author who crafted an anti-fascist epic about a panorama of people struggling against an abusive power (who also happened to be zoophagous alien reptiles). If you recall Kenneth’s Johnson’s brand of humanism and science-fiction excitement from his television work, The Man of Legends may be the best new novel you read in 2017.

The book initially presents itself as an historical mystery in line with a Dan Brown thriller. In New York City on the weekend between 2000 and 2001, a reporter for a sensational tabloid magazine makes a bizarre discovery: three photographs spread over a hundred and fifty years containing images of what appears one man — who is the same age in each picture. The reporter, 27-year-old Jillian Guthrie, sees the man on a television news story and believes she’s stumbled onto the most astonishing find in history. Not to mention a path out of a dead-end journalist job.

Although Jillian chasing after the mystery man is a major through line, The Man of Legends is more than a rote investigator story. The novel is presented in the form of an oral history Jillian Guthrie collected after the fact, bringing together accounts of people from across New York who were witnesses to the astonishing New Year’s events around the ageless man who currently calls himself Will. Will’s own firsthand account is included: his complex history unfolds piece by piece as the other narrators create the glue holding it together.

This is a difficult narrative structure to tackle for any author, since it requires juggling more than a dozen characters with unique voices. Over the course of the story, we hear from an 85-year-old former UN envoy, a teenage graffiti artist, a washed-up country musician, a book editor, a Harlem bartender, a Japanese-American taxi driver, a Catholic priest working as an agent for the Vatican, a homeless woman, and an orphaned five-year-old girl. It would be easy for a writer to get lost in such a mass of voices and take the reader down with them. But Kenneth Johnson is a steady hand on the tiller thanks to years of experience working on multi-character dramas. Some of the narrators are only present for brief periods, a few pages, but each appears for a purpose and leaves an imprint on the story. Only one major character does not have a direct voice as a narrator — but there’s a good reason for it.

The story opens on December 31, 2000. Readers learn enough about the enigma of Will to want to pursue him the same way Jillian does. Will has apparently been alive for around two thousand years. His knowledge is vast and varied: in a Harlem bar he shows he can quote Pascal in the original French and understands Aramaic. He’s a skilled artist and has written history books that have a peculiar immediacy. The Catholic church has chased him relentlessly for centuries. But Will is not only running from the church and its current agent (Father St. Jacques, the story’s Jack McGee/Inspector Javert equivalent). He’s dogged by both a curse and a self-made burden of responsibility. The curse remains disguised during most of the novel’s first half, emerging in fragments in the second half. But Will’s personal burden is clear early on: he’s attempting to aid humanity by passing information among the people throughout history who can make a difference with the knowledge.

Much of Will’s narration delves into his historical sojourning, and Kenneth Johnson has a feverishly good time dropping his central character into key points of history where he can meet great thinkers and movers. Will sails with Herman Melville; advises Mark Twain to go look into a celebrated jumping frog in Calaveras County; helps James Watt develop a steam engine; brings Kepler a telescope from Galileo; goes on the Salt March with Gandhi; recommends movable type to Johannes Gutenberg; inspires Mary Shelley’s most famous story; and speaks with Henry David Thoreau at Walden about “a way of living right.” He even gives assistance that helps result in Levis and espresso.

Much of Will’s narration delves into his historical sojourning, and Kenneth Johnson has a feverishly good time dropping his central character into key points of history where he can meet great thinkers and movers. Will sails with Herman Melville; advises Mark Twain to go look into a celebrated jumping frog in Calaveras County; helps James Watt develop a steam engine; brings Kepler a telescope from Galileo; goes on the Salt March with Gandhi; recommends movable type to Johannes Gutenberg; inspires Mary Shelley’s most famous story; and speaks with Henry David Thoreau at Walden about “a way of living right.” He even gives assistance that helps result in Levis and espresso.

But Will’s goal to create a better humanity — and potentially lift his own curse — runs into a conundrum during the finale when he faces the other figure who has pursued him across centuries: “No Good Deed Goes Unpunished.” For all the benefits Will has attempted to bring to the human race, has he also brought additional suffering? Will once discussed the right way of living with Thoreau — but is such a thing achievable, even for a man who has lived hundreds of lifetimes?

This is where The Man of Legends pulls off its most impressive feat: using the combined presence of all the narrators to reflect onto Will as the climax constricts around him. The story does not belong exclusively to Will. It’s also the story of people like Jillian Guthrie, who suffers from an ingrained racism she eventually confronts; and of Tito Brown, the graffiti tagger who discovers his greater purpose when his mind opens up in the artistic vastness of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (the novel’s most impressive sequence). It’s even the story of the ostensible villain, Father St. Jacques, whose confessional diary entries show a different kind of struggle toward “a way of living right.” Johnson invests each character, even those with the briefest time on stage, with their own journey that reflect Will’s, and he makes readers feel a personal attachment to every one of them.

To say more regarding the revelations about Will’s existence and its ultimate message would be to say too much. The book deserves to have readers walk at the characters’ sides and learn with them along the pathways of history and the canyons of New York at the start of the new millennium. The Man of Legends works excellently as a thriller, a panoramic trip through the past, and a character study of a cast drawn from all strata of life in NYC. But the thematic unity that urges readers to join the characters in looking beyond their immediate lives is what makes it memorable. What Kenneth Johnson achieves through the numerous character arcs and two thousand years of time is an experience that is as intimate as … well, as talking with Henry David Thoreau.

I had the opportunity to talk to Mr. Johnson on the phone a few days after reading an advanced copy of The Man of Legends. His publicist recommended a phone call rather doing the interview via email, “because he’s so wonderfully engaging and interesting to talk to.” I armed myself with a digital recorder and called his Sherman Oaks office on a Wednesday afternoon. After introducing myself to his receptionist, I was transferred immediately to … well, when I asked him if this was Mr. Johnson, he answered, “No, this isn’t Mr. Johnson. Mr. Johnson is my father. My friends call me Kenny. You can call me Kenny.”

And this launched into an hour-and-a-half talk that, if time had permitted, might have stretched to three hours without even a pause. His publicist perhaps underplayed how engaging Kenneth Johnson is in person as well as on the page and screen. I rarely needed to pursue a topic with him; he answered many of the questions I planned to ask without me needing to ask them.

Around halfway through the interview, I realized there was too much fantastic material for a single post. I’ve split the Q&A into two parts. This week I’ll feature the section of the interview where we talk about The Man of Legends, the influences behind it, and the creation of the audiobook version. Next week we’ll focus on his television work, specifically The Incredible Hulk and V: The Original Miniseries.

Q&A with Kenneth Johnson, Part 1

You probably hear this all the time but… I grew up with your material. Your shows were some of the first I watched as a child that used adult dramatic themes. The Incredible Hulk is still my main lens on the character. And V: The Original Miniseries was — for elementary school kids — the most epic thing we’d ever seen on television. Unlike many shows I liked as a child, these still hold up today.

Thank you. It was very sweet what you said. It’s funny, many people, as I tend to get older, say, “I grew up watching your stuff.” And my response has very often been, “I grew up making them!” I was the youngest writer-producer on the lot at Universal. (And, P.S., the lowest paid!) But it was really great fun. My years at Universal doing the Bionic shows: I always looked at them like graduate school with pay.

You’ve written novels before. The most recent was V: The Second Generation, which is a direct sequel to V: The Original Miniseries. What made you want to go back to writing a novel, in this case one that was original and not based on any of your previous works?

You’ve written novels before. The most recent was V: The Second Generation, which is a direct sequel to V: The Original Miniseries. What made you want to go back to writing a novel, in this case one that was original and not based on any of your previous works?

What happened was I discovered a character — a character people have heard about, a legendary character. But nobody had really dug into it. I think I first came across his name when I was reading a book by Mark Twain. It was a book he had written in the 1860s called Innocence Abroad. It was a travelogue, essays that he sent back to a newspaper about his travels overseas. He talked about being in the Holy Land, and he talked about being at the place where this character originated two-thousand years ago. And then I discovered, as I was beginning to dig in a little deeper, that Percy Shelley, fifty years before Mark Twain, had written a couple of poems about him, apparently having met him. And then I thought, “Okay, wait a minute — who is this guy?”

And the more digging I did and the deeper I went I discovered that there were reports about people having encounters with this man in the 1600s and the 1400s and the 1200s. The deeper I got, I realized that, wow, if there’s a man who’s going to be alive this long, traveling across the world for twenty-some centuries, he’s going to encounter a whole lot of people. A lot of them could conceivably be famous historical figures. Okay, how could he have impacted those people and inspired them in various ways to end up changing the course of human history? The thing got bigger and bigger the deeper I got into it.

I actually started writing it as a screenplay. But then realized I couldn’t possibly service this character or his story in two or two-and-a-half hours. It needed to be a longer piece. And the more I thought about it, the more I thought it would be really fun to do it as a novel so that I could really get inside his head, as well as the other people who become witnesses to what happens in New York City over New Years’ weekend of 2000 and 2001, which is the time the story takes place — albeit with flashbacks over two thousand years. I realized how much fun I could have involving him with real historical figures. How he could have been a shipmate of Herman Melville’s, and even maybe have saved Melville’s life. So I blended the fiction I was creating with reality: suppose my guy had been the one who suggested to this metalsmith named Gutenberg, “How ‘bout using movable type?”

He could’ve sparked Gandhi and inspired Gandhi’s Salt March primarily so he could spend more time in Gandhi’s presence because he had to keep moving constantly. Or could he have inspired Einstein or helped put Galileo in touch with Kepler, or helped inspired Levi Strauss to make what became a very popular style of clothing?

Well, I’m wearing them right now.

There you go! We and so many of us are. When I saw that Percy Shelley had been involved with him, I said, “Well that means Mary Shelley must have been involved with him.” So to be able to put him in that Swiss chalet the evening that Lord Byron suggested to Mary and Percy Shelley and a couple of other people that they tell stories of the macabre. She’s working on this novel at age 19 about animating a dead body. But she’s stuck on how she’s going to do that. My hero, Will, gives her the suggestion that allows her to bring the Frankenstein Monster to life. There’s other stuff as well: how he helped send Al Capone to prison … You know, it was so much fun to weave all of that into a novel that really had some substance and some depth to it, I hope.

The novel has a number of echoes in it from The Incredible Hulk —

Including an exact quote: “Don’t make me angry. You wouldn’t like me when I’m angry.” When I came across that, I thought, “He couldn’t resist it, it had to be there.”

Well, it was appropriate, you know. Wherever I can slip in a little something that can make my old friends smile, I always try to do that.

One question that occurred to me when that happened, when Will is talking to “the young man”…

“The sleek young man.” I always use Jude Law or Leonardo DiCaprio in my head when I was writing that particular character.

Good casting! But at that moment I was thinking, “Would Bill Bixby have been a good Will?”

Oh yeah, of course!

That was the point where I realized there much similar between the way Bill Bixby played David Banner and the way you wrote the character of Will. He travels continually and cannot help himself when it comes to aiding people, even if it’s going to majorly backfire on him — which it inevitably does.

That was the point where I realized there much similar between the way Bill Bixby played David Banner and the way you wrote the character of Will. He travels continually and cannot help himself when it comes to aiding people, even if it’s going to majorly backfire on him — which it inevitably does.

Exactly! More often than not — and it certainly happened more often than not on The Hulk — that’s what I was looking to do. Humanism is very important to me; it always has been. I’ve always been eager to try to stress as much humanism as I could in my work. Certainly that came through in a lot of the episodes that we did of The Hulk. And in what I’m trying to do in The Man of Legends is to make people think a little bit, to give them a little … well, in some ways, the theme of the book is trying to discover one’s reason for being. Because of the mistake that Will made initially — I mean, he’s a flesh-and-blood guy, but he made a mistake like you or I could easily make — because of that, he has had these extremely grave circumstances come down upon him, and he’s had to travel the world for the last two thousand years. He can’t stay in one place more than three days and has to be moving on. So he’s trying to understand why. Why does this happen? And several of the principal characters of the book are also on that same sort of character arc. They’re trying to discover exactly what their reason is for being. Exactly why is Jillian such an intolerant and prejudiced person in some respect? And the priest himself, who is an envoy of the Vatican. The Vatican has been chasing our hero Will for almost sixteen hundred years, eager to contain him because of the treasure he represents to their empire, but also the danger that he represents to their empire, and to organized religion in general, because of what he knows.

When I began to get interested in the character, I realized that it was such a rich character to explore. As I was going along, as I was doing it, and suddenly realized — as you did — that there are echoes of The Hulk in here too. He’s being pursued by an Inspector Javert who in this case is a French priest who is very devious, duplicitous, clever, and determined to be the one who brings their quarry to ground. But Will is also being sought by these two very different women, because I was very eager to get that perspective. One of them is the newspaper reporter for a tabloid like the National Enquirer, just like Jack McGee on The Hulk. In fact I used the same newspaper, the National Register, in the book that’s same one McGee worked for.

Oh, I didn’t catch that.

She is pursuing him because she’s seen him in three different photographs, looking the same and unaged in spite of the fact that the photographs were taken a hundred and fifty years apart. Then she chances to see this TV newscast where this unidentified man, obviously heroic, has just rescued a five-year-old Latina child from a flaming tenement house in Spanish Harlem. The fiery walls collapsed on him, and he was burned over ninety percent of his body, his bones are broken, he’s in a coma, not expected to live — but as he being shoved into the paramedic van, she sees him on the newscast and his face, and she says, “Holy cow, it’s the guy! Wait a minute!” So she’s after him.

Maybe one of my favorite characters in the book is Hanna Claire. Hanna is sort of an eighty-five-year-old Katherine Hepburn yankee, feisty woman, envoy of the United Nations. But sixty years ago, she was the love of his life when he saved her life from her oh-so-romantic attempted suicide in the River Seine, and then traveled with him for a year, and she became the love of his life and sort of back and forth. But he separated from her after a year because he didn’t want to see the pain of her growing older while he remained young. He had lived through that with his wife and children two thousand years earlier and had since tried to avoid it. But Hanna was unavoidable because she was just … I think incandescent is the word he used to describe her. So she is eager to find him and be reunited because she is slipping to Alzheimer’s. A sort of cross-the-ages love story that I was trying to do.

The other character who is also pivotal, whom you touched on: he’s only ever described as “the sleek young man,” and then you can see why I wanted to go to Jude Law or Leonardo DiCaprio in my head. He has been shadowing our hero for the whole two millennia, which makes us think, “Wait a minute, maybe he’s an emissary from darker forces” — which indeed of course he is, as we discover as we go along. But he’s also incredibly charming. It was fun to try to blend all those together into a book that I think could have the same king of appeal that The Hulk had or V has had, which it will appeal to a broad range of people. At least I hope it will, because it’s got some important things to say about the right way to live and the right kind of person to be. If I can just spread a little bit of that around, I will have achieved a whole lot in my estimation.

There moments in the book I thought showed some of the influences on it. One is a first-season Twilight Zone episode, “Long Live Walter Jameson,” written by Charles Beaumont.

There moments in the book I thought showed some of the influences on it. One is a first-season Twilight Zone episode, “Long Live Walter Jameson,” written by Charles Beaumont.

It’s so funny you mention that one. I was in college when The Twilight Zone was in it’s heydey, so I wasn’t watching a lot TV. I did see several episodes, and Rod [Serling] actually came to speak at Carnegie while I was there. Because it was such a “Theater!” school, hardly anyone had any questions for him about television. I was able to ask quite a few. When I met him many years later on in California, I reminded him of that. And he said he remembered me because I was the only one asking questions. It was funny to hear.

My daughter Katie, who’s in her thirties now, probably about your age, she is a Twilight Zone guru. She said, “You know, you really ought to take a look at this.” Now this is something she said about a month and a half ago. I had never seen that episode. She gave me her copy of it, and I looked at it and I thought, “Oh, wow. Okay, there are a lot of similarities.”

Such as the photos of a living man taken over a hundred years ago — where he looks exactly the same as he does today.

Yes, there are the photos. There’s one taken in the Civil War. Wow, perfect! When I did V, a number of people said, “Oh, you’re doing Childhood’s End.” And I said, “What?” I’d read a lot of Arthur C. Clarke but I had never read Childhood’s End before I did V. And yet there were a lot of obvious similarities in that, too.

The Man of Legends was already in galleys before Katie said, “Hey, Dad, you ever see this one?” She’s constantly surprising me with episodes that I had never seen of The Twilight Zone. It’s funny: I was just invited back to the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory last week to deliver a presentation about how I’ve used science fiction to promote thought and tolerance and unity. It was an interesting experience to be among … well, there are geeks and then there are these ultra-brilliant geeks, and I was among two hundred of them last week, and it was an honor to be among such an erudite and incredibly smart crowd of folks. And so many of them, by nature of who they are what they do, are acknowledged geeks and proud of it — just like my daughter is.

Well, like your daughter, I’m a complete Twilight Zone geek.

There you go! And how could you not be? The writing was so extraordinary, and how they were able to put it together and sneak things through that the public and the network didn’t realize were getting snuck through on them. Which is always good.

One of the early reviews for The Man of Legends says, “Without question Kenneth Johnson is the closest our generation will come to the great Rod Serling.”

Wasn’t that a wonderful thing for somebody to say?

I can’t imagine being complimented any better than to be compared to Rod Serling.

You’re right. It’s absolutely true. When I did V there were one of two reviews that said, I remember, “Well, it’s not quite Orwell, but…” And I said, “No, no, no, I’ll take that! Wait a minute, my name’s in the same sentence as George Orwell — even if it’s ‘not quite’ Orwell?” It’s so flattering to see that happen.

But the main thing I’ve always been interested in trying to do is to tell a story that people will get caught up in — and then slip into that, wherever I possibly can, some substance. I love to try to get people into the store from the shiny commercial appeal of a concept, perhaps. It’s sort of a tacky way to say it, maybe. Because that’s what the spaceships and the reptilians in V were all about. To get people to say, “Wait a minute, what is that?” And once I had them, I could begin to tell them the story I wanted to tell, and to try to move them in a way that would help them to be better human beings, to be better people.

I was an only child and raised in a virulently bigoted, anti-Semitic household. It was really a dark situation. I always think of Oscar Hammerstein’s song from South Pacific, which he won the Pulitzer Prize for (rightly so), which says: “You’ve got to be taught before it’s too late, | Before you’re six or seven or eight, | To hate all the people your relatives hate. | You’ve got to be carefully taught!” For some reason, I didn’t buy the bigotry. I just knew instinctively it was not the right way to live. It was not the right ethic to have. I don’t know where that came from in me; I’ve never been able to quite figure that out. But it’s true. And that’s why I was talking about it at APL last week in Baltimore. It just rubbed me the wrong way constantly. I just couldn’t use the hate words I heard all the time. I was able to really attack it head-on later in my life when I did the Alien Nation series and the series of movies, because it gave me a chance to confront intolerance and prejudice head-on. And that’s one of the themes that I’ve tried to weave through all of the stuff that I’ve done. I think it’s a vital thing for people to constantly think about and realizing the right way to be.

This comes through in the character of Jillian Guthrie in The Man of Legends.

This comes through in the character of Jillian Guthrie in The Man of Legends.

Exactly, because Jillian is not all that terribly likable from the beginning of the novel. I recognized that, and some people may have difficulty with it. But she also explains early on that it’s painful for her to recall that this is how she was. That’s the only way we can really appreciate the arc that she has followed. The change that has overcome her because of encountering our hero. The same is true of so many of the other voices of the piece. I chose to write the novel, as you saw, in multiple first-person accounts from the people who were eyewitnesses to this New Year’s weekend in Manhattan, and from the first-person standpoint of our hero as well so that we could really travel back with him in time to see the encounters that he’s had.

I’ve got to say, it was tremendous fun recording the audiobook version because I brought in a dozen or more of my favorite actors, including several of my friends from my Alien Nation days, to play the characters. It was like it we were doing a radio play. The Amazon people have been very excited about it. They said they’ve never had an audiobook that sounds quite like this one does.

My favorite of all the various narrators is Tito Brown, the seventeen-year-old mixed-race graffiti artist.

Tito’s a real character in the sense that he’s a real person whom I knew. I got intrigued by the graffiti artists who painted the sides of subway trains back in the early ‘90s, and went back and really did some deep research and spent a lot of time with them. I even went up in the “layups,” as they call them, which are the railyards up in the Bronx where these guys go out in the middle of night with flashlights and spray the sides of trains. And it was not to deface them, it was really an artistic endeavor.

Tito is a composite character based on three separate guys that I knew at that time. He’s a pretty real guy. Where he lives — I’ve been in those places that he’s describing. What I was eager to do is show a sort of spectrum of New Yorkers, of which he is the most sort of “streetsy.” It was great fun to craft his speech and his dialogue the way that I had actually heard it myself.

As you can see in the book, what I’m trying to do is a little like a Ken Burns documentary, where a journalist — in this case our leading lady Jillian — has collected the people who were eyewitnesses, herself one of them, and recorded the story in their own voices. To me it added a little extra sparkle and spice to the reading experience. And then particularly the listening experience for people who get the audio book. It really does come off like a radio drama, and to me, of course, it’s theatrical, which is where my roots are, so to actually hear them reading the words was really a kick in the recording studio.

Having read this book so closely to re-watching V: The Original Miniseries, I noticed a similarity in writing style. V has to work with a huge cast of characters who rotate and show a spectrum of opinions. I have to imagine that experience was the right kind of teacher for writing this type of book.

Having read this book so closely to re-watching V: The Original Miniseries, I noticed a similarity in writing style. V has to work with a huge cast of characters who rotate and show a spectrum of opinions. I have to imagine that experience was the right kind of teacher for writing this type of book.

And let me tell you what the right teacher was for writing V. The year before I wrote V, I read War and Peace for the first time. I was totally blown away by the way Tolstoy could take such a spectrum of characters, all seemingly sort of spread out all over the place, and in the course of this wonderful piece of writing, bring them closer and intertwine them until they were locked together. It was like — wow!

I always want to bring this up when someone mentions it: when I finally read War and Peace all I could think was: “Damn.” It’s a book that gets talked about in an offhand way, “Oh that’s that big thick book.” But it’s one of the most remarkable feats of literature I can imagine. You have never read characters like these before.

When I read it before V, I read the translation that had been in vogue for years. But when the new translation came out a few years ago…

The Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky translation.

Yes. When I got to reading the reviews, and the “drops dripped” in the translator’s introduction… [The shortest sentence in the book.]

That was an observation that struck me as well.

I looked at [my wife] Susie and I said, “I have to go back and read it again.” And I did, and I loved every moment of it. I could start it again today and still be just as amazed as I was that first and second time that I read it. It really was what inspired me to write V the way that I did. And also to write The Man of Legends in a similar vein, where I’m looking at a very disparate group of people that all bring their own unique voices and experiences to it.

The priest also is interesting because a few years ago I read The Confessions of Saint Augustine. I was really amazed by, first of all, how absolutely interesting and personal it was. It didn’t come off as some sort of religious tract. This is a real guy! He wrote the whole Confessions as though they were confessions to his god. So I thought, “Wow, what an interesting way to have the priest tell his story, as if he’s writing it in his diary as though he’s writing to God,” and at the same time weave into it, between the lines and in the subtext, “I don’t know that my simple work here will ever achieve any kind of publication. I have not the faintest hope that it might … unless it be thy will, of course, Heavenly Father.” He’s always sort of baiting just a little bit: “Help me out here, Heavenly Father.” I thought it was an intriguing way to weave him into the story.

Wow, when you say a book was influence by St. Augustine and Leo Tolstoy…

Wow, when you say a book was influence by St. Augustine and Leo Tolstoy…

Yeah, it sounds so damn pompous, doesn’t it?

But we have to learn from the best!

That’s it. Somebody at the Q&A at Johns Hopkins last week asked, “Were you influenced by the television show The Fugitive doing The Hulk?” And I said, “No…” Again, I was in college when The Fugitive was running and I never really saw it. I was influenced by Victor Hugo and Les Misérables. That’s where so many of my inspirations have come from: I’m a great reader of history, and I love it. Doing this book was a joy in the research level because of everything that I was reading, digging into history, which was so cool, and using the knowledge that I had gained of history over the last twenty or thirty years of really conscientious reading, and finding ways to have my hero affect those historical situations and be in the right place at the right time to inspire somebody. He helped to create the compound microscope, which in turn created the science of biology. He helped James Watt, the Scotsman, to try to get his machine working; suddenly our hero says, “You know, there’s something I remember from my travels to Egypt all these years ago,” and he gives him the idea of how to make the steam engine work.

And creates espresso as well!

Oh yes, you got it. The great fun is, tangentially, he uses the steam on the first steam engine to create the first cappuccino. I love being able to do that kind of stuff. Some people will think that’s kind of silly, but what I was looking to do was see how my hero could have affected all of human history. As you know from reading the book, it wasn’t all good. It seems to be a good thing when you save a little Bavarian boy from freezing in a blizzard in the Alps — until you realize the boy grows up to be the grandfather of Adolf Hitler.

He also helps Albert Einstein — and Hiroshima is destroyed by an atomic bomb.

That’s exactly right: NGDGU, “No Good Deed Goes Unpunished.” It was interesting to see that sort of thing. And the guilt my hero felt from realizing that by saving that kid Hitler and the Holocaust came along, he became part of the Valkyrie plot to assassinate Hitler. And he’s condemned and hung on a meat hook, but of course, being who he is he goes through all the pain of that — can you imagine? — and still survives and goes on. That’s part of the fun I had in trying to put the book together. I’m really hoping that it finds an audience.

It seems to be, incidentally. Amazon made Man of Legends one of their selections for Kindle First. So although it doesn’t release in print and audiobook and digital until July 1, last Thursday they released it on Kindle First and it was an instant bestseller. It’s been in the top four of the one million titles on the Kindle Store and has been since it went up. For me, more importantly than that, the reader review ratings have been 4.3 out of 5 stars, which is really rewarding to see and gratifying.

I think something that helps get the book across is that it projects to a potential reader that it might be a Dan Brown-style thriller. But it’s far better than that. Dan Brown offers the concept of an historical mystery. People enjoy that; they want to read that. But you provide an historical mystery with a humanist theme and characters who are more than plot mechanics. It’s not just a series of puzzles. It ties together characters of different backgrounds and races in a way that’s pertinent and powerful.

Oh, thank you!

The sequence in the book that’s my favorite is something you’d never find in a Dan Brown novel, which is Tito Brown going to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for the first time. Dan Brown wouldn’t give you a sense of wonder about the Met. He’d use it as a prop. Tito’s experience at the Met is something to enjoy vicariously as readers understand why it’s meaningful to him. I’ve been to the Met, it was amazing to me, but I would never experience it the way he did.

Of course not; you couldn’t have. I can’t tell you how rewarding it is to hear that. You’re the first person who has flagged that and mentioned that particular part to me. I really tried to write it and transcribe it the way I heard Tito tell me about it, look at it through his eyes: this kid from the Bronx who has never been to 5th Avenue before, and is suddenly confronted on 88th Street with this — I think I described it as something out of Gladiator — this gigantic edifice! And him thinking, “They’re not going to let me in there, man!”

And everybody’s kind to him and learns about chiaroscuro and more. To see it through his eyes and to maybe give some kid who’s never thought about going to the Met the idea that, “Wow, I ought to go there and take a look at things.”

It provides a perspective people may not have. The assumption is that if you live in New York City, of course you’ve gone to the Met. Why wouldn’t you have? There’s a realization that Tito never even knew this place existed. It gives you a sense of perspective on New York City, the different people in it, and how they experience the city. On one hand, you have a person like Hanna Claire, a wealthy member of intellectual high society, who probably visits the Met four times a month. Then you have someone like Tito, a poor teenager who understands the use of color in art entirely through the lens of types of spray paint, who was unaware of the museum until Will told him to go to it.

It provides a perspective people may not have. The assumption is that if you live in New York City, of course you’ve gone to the Met. Why wouldn’t you have? There’s a realization that Tito never even knew this place existed. It gives you a sense of perspective on New York City, the different people in it, and how they experience the city. On one hand, you have a person like Hanna Claire, a wealthy member of intellectual high society, who probably visits the Met four times a month. Then you have someone like Tito, a poor teenager who understands the use of color in art entirely through the lens of types of spray paint, who was unaware of the museum until Will told him to go to it.

That’s what intrigued me about Tito, and following his character arc through “What’s my reason for being?” and “How can I be better at what I do?” Of course, that’s what Will is trying to inspire in everyone. With Tito, with a former country music star who’s gone down in the bottle … When you hear it on the audio recording, he actually sings the song for me at the end it. It’s great.

How did you find a good voice actress to play Maria, the five-year-old girl?

That’s was extraordinarily challenging. I had wanted to use my nine-year-old granddaughter, Lily, who is quite adept at reading. She’s not an actress type at all, but she’s really bright and a good reader. But Amazon would not let me hire anyone under the age of eighteen. I was stunned, because when you’re making movies you hire a kid, you have social worker there to make sure that they’re getting taken care of properly. But Amazon said, “Nah, won’t do it.” I auditioned on tape about half a dozen talented women who were able to get really close. But I thought the character, because she is Hispanic, ought to have a little bit of an Hispanic dialect. And the woman that I thought was so good couldn’t do it. She said, “I can’t get there. I can get the five or six-years old” — and she really could — “but not with an Hispanic dialect.”

Then I discovered Francesca Ling. It’s so funny, because she’s a robust, exotic woman with gobs of wonderful dark hair, and an extraordinary figure, a woman that people will turn around and watch go by on the street. And she steps into the booth and this little voice of this five-year-old child came out of her, and all of us were just … I mean, I was gobsmacked with the audition tape that she sent over. But to hear that come out of the booth and then to take a break and ask her a question and she’d answer in her grown-up adult Francesca voice — it’s was totally jarring. Wait a minute, are there two people in there? She was a real find as you’ll hear when you get the audio version.

Of the various narrators, who was the toughest to write?

I think probably the child [Maria] was, because it had to be done so carefully so that it was from a perspective of absolute innocence. We’ve all seen child characters in film, television, and theater who just don’t talk like children do. They’re using words that they don’t. That they shouldn’t. I think in trying to get Maria right so that she both sounded real with the right level of innocence while still getting across the really ugly, awful points I had to get across through her dialogue — that was probably the biggest challenge. But I welcomed it, I was really pleased about it.

Was The Man of Legends your original title for the book?

My original title was The Legend of W. J., and I loved the fact that people call Will by W. J. and J. W. and all these different names. The Man of Legends was not my first choice as a title, but when you’re dealing with publishers … well, there you go.

Thank you for taking the time to read the book. What a concept!

I imagine you’ve had interviews with people who haven’t read it.

You’re talking to the guy who produced The Mike Douglas Show all those years ago. We had a lot of authors on, and let me tell you: Mike Douglas never read a book in his life. We had to feed every question to him from one of us who had. When you’re doing that on an ongoing basis, who’s got time to sit down and read a book, especially if it turns out to be turkey?

And this is the perfect point to end Part 1 of the Q&A and segue into next week, when we talk about the early part of Kenneth Johnson’s career in daytime television and his work on his now legendary shows.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.