Things Your Writing Teacher Never Told You: Getting to Know Your Omniscient Narrator

With the exception of “Folksy Narrators” we often think of omniscient narrators as omnipotent sky-gods who are so vast and powerful that they’re unknowable entities. But looking at them that way hides away a helpful tool in crafting and revising our fiction.

(My blog on folksy narrators is here.)

On Friday, I was leading a seminar for Myth-Ink, the Columbia College genre writing student group, on how to do public readings. They were gearing up for when they’ll be the featured readers at my Gumbo Fiction Salon reading series next week. One of the young women was practicing the first two pages of a story about dragons. Her first read-through was fairly lifeless. She didn’t have confidence in her own vocal skills, and it didn’t sound like she had confidence in the story. We had already gone over many of the basic tips, so I took another tack. I asked her some questions.

“Who’s the narrator?”

“They’re not a character. It’s omniscient POV.”

“Fine, but who’s the narrator? Male or female?”

“Female.” That answer came quickly. The next took some thought:

“Young, middle-aged, or old?”

“Middle-aged,” she decided.

“Does she like the dragons or fear them?”

“She likes them.”

“Does she like them to the point that she sides with them, or she’s rooting for them, or she likes them as long as they’re on the other side of the zoo wall?”

“She sides with them.”

“Good. Now read your first two pages again.”

The difference between her first and second attempts was extraordinary. She spoke the narration with authority and warmth. She emphasized certain words and lingered on meaningful phrases. She brought the words to life!

She was reading from her phone, so she hadn’t marked up a manuscript to circle strong verbs or underline key phrases. (Something I recommend to anyone who asks about doing public readings.) And she didn’t spend any additional time looking over the text.

The only thing that happened between the first wooden rendition and the second vibrant reading was that short series of questions and answers. Simply by discovering who her omniscient narrator was, she was able to bring the words to life.

As a group, we talked about the importance of inhabiting the characters during a reading. I told them they shouldn’t be an author reading a story aloud; they should be their characters reliving and recounting their story. It’s make-believe, but with more polished prose.

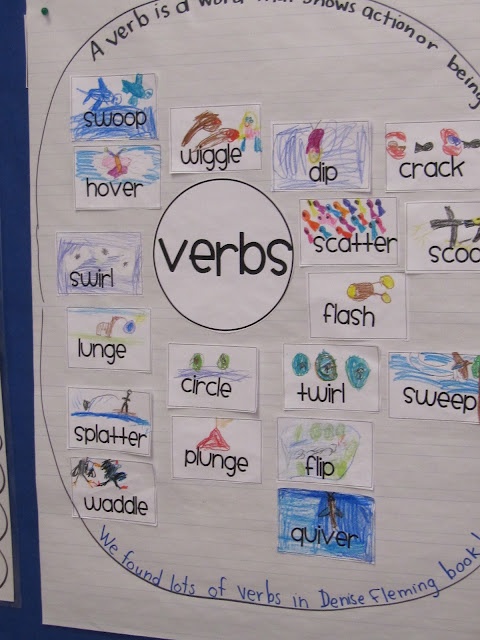

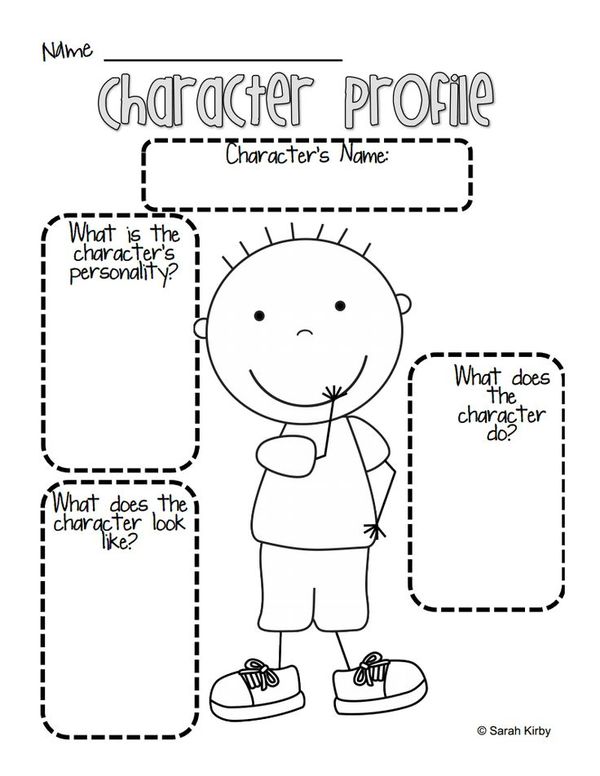

Most writers spend a fair bit of time working on characterization. Some work up character profiles from a fiction worksheet. (I’ll share my profile sheet in the next blog.) Some modify the character and stat sheets from gaming. One writer I know even uses the gaming dice to determine the properties, and takes what he roles, rather than setting the stats to be most beneficial to the story. Some draw their lead characters, or find a picture on the internet to represent them. Some journal in the voice of their characters. There are lots of techniques for getting to know them, prior to writing the story.

But I’ve never heard of working up a character profile for your omniscient narrator. In retrospect, it seems rather obvious. As both writers and readers we give them a shocking amount of trust and intimacy while knowing almost nothing about them. Perhaps that’s why I generally prefer to both read and write fiction with a First Person or Tight Limited Third POV. (I discuss those POV options in detail in this blog.)

If you’re in a close POV like that, you’re inhabiting their brain; you get to know a lot about them. You can generally judge whether they’re a reliable source of info about different things. You can spot their blind spots or misperceptions. An omniscient narrator has lots to say on a lot of topics, but we have very little info on how to judge them or weigh their views.

The exception to this is often the folksy narrator. We have no trouble figuring out the basic character of Terry Pratchett’s omniscient narrator in the Discworld books, for instance.

As authors, we subconsciously know at least a little bit about the views of our omniscient narrators. The student knew immediately the gender, age, and views about dragons. A narrator who fears dragons is going to color the narrative in one shade, while a narrator who roots for dragons would color it in another.

But, if we take time to consciously get to know a bit about our narrator, it gives us a helpful tool in analyzing why a story isn’t working. If we know the narrator’s biases, we can judge where they went off the rails in telling the story, or even if they’re the right narrator to be telling the story at all. It may even reveal a subconscious truth the author has been hiding from themself. That can be anything from a personal issue to a problem in the plot.

The next time you start to write a story with an omniscient narrator, I encourage you to spend a little time interviewing them first.

If you’ve enjoyed this blog, you might want to check out the other entries in my never-ending series about Point of View.

Part 1: A Few Questions to Get You Started

Part 2: Who is Your Point of View Character?

Part 3: A Closer Look at Some POV Styles Commonly Used in Fantasy (Starting with Some Intriguing Uses of 2nd Person)

Part 4: 1st Person and Tight Limited 3rd – A Closely Related Duo

Part 5: The Younger Sibling of 1st & Tight Limited 3rd: Simple Limited 3rd & The Case for Choosing A Single-Character POV

Part 6: Serial POV – In its Myriad Forms

Part 7: The Multiple Personalities of Omniscient 3rd Person: Spotlight on “Reporter”

Part 8: The Multiple Personalities of Omniscient 3rd Person: Spotlight on “Head-Hopper”

Part 9: “Head-Hopper” – A Correction and a New Example

Part 10: The Multiple Personalities of Omniscient 3rd Person: Spotlight on “Folksy Narrator/ Storyteller”

Others in my craft series include:

The 9 Aspects of Story Promise

A Look at How Peter Straub Crafts His Opening Chapters

Researching the Tropes

Seven Common Approaches to Stories That Use Mythology, Fairy Tales & Other Established Source Material

It Was Only A Dream…

Story in Its Many Forms

When the Form Is the Story

The Skeleton Matters (Or, Why It’s Not OK to Skip Scenes in Your Third Act)

Tina L. Jens is a 2017 Rubin Family Fellowship recipient for a residency at the Ragdale artists retreat. She has been teaching varying combinations of Exploring Fantasy Genre Writing, Fantasy Writing Workshop, and Advanced Fantasy Writing Workshop at Columbia College-Chicago since 2007. The first of her 75 or so published fantasy and horror short stories was released in 1994. She has had dozens of newspaper articles published, a few poems, a comic, and had a short comedic play produced in Alabama and Florida and two others chosen for a table reading by Dandelion Theatre in Chicago. Her novel, The Blues Ain’t Nothin’: Tales of the Lonesome Blues Pub, won Best Novel from the National Federation of Press Women, and was a final nominee for Best First Novel for the Bram Stoker and International Horror Guild awards.

She was the senior producer of a weekly fiction reading series, Twilight Tales, for 15 years, and was the editor/publisher of the Twilight Tales small press, overseeing 26 anthologies and collections. She co-chaired a World Fantasy Convention, a World Horror Convention, and served for two years as the Chairman of the Board for the Horror Writers Assoc. Along with teaching, writing, and blogging, she also supervises a revolving crew of interns who help her run the monthly, multi-genre, reading series Gumbo Fiction Salon in Chicago. You can find more of her musings on writing, social justice, politics, and feminism on Facebook @ Tina Jens. Be sure to drop her a PM and tell her you saw her Black Gate blog.

I’m currently most of the way through Stephen King’s IT (for the first time in about 27 years) and it’s interesting — he does what I’d describe as semi-omniscient (usually staying fairly close to one character, but not afraid to move around, in a way that doesn’t strike me as jarring) and with a tone that kind of splits the difference between folksy and sky-god.

I haven’t read _IT_. That sounds like a really interesting POV choice. It takes a deft hand to do what you’re describing.

I think in a lot of ways King is a much better nuts-and-bolts writer than he’s given credit for.

(Having said which, he’s certainly not without his flaws — endings in particular seem to give him a surprising amount of trouble.)

I’m not that familiar with King’s work. I’ve sampled him here and there, but found his male protags to generally be too misogynistic and the violence to be too graphic for my personal taste. I’m not saying he’s a bad writer or that all his work is misogynistic; I’m just saying I haven’t connected with the work that I’ve sampled.

Yeah, that’s entirely fair. It doesn’t matter if he’s a good writer if what he’s writing isn’t something you want to read …

I get, to an extent, what Joe H. says about King and endings: the end of the book version of “Under the Dome” was a MASSIVE disappointment, as was “The Shining,” and “Carrie” was unsatisfactory all the way through. But — The full-length “The Stand” was one I literally could not put down; “‘Salem’s Lot” is one of the best all-time vampire novels; and I’ve thoroughly enjoyed the first 5 novels in “The Dark Tower” series. I’ve been an avid reader for 55 of my 66 years, and as a college English professor, often read stories and poems aloud to my Basic Lit. class, and always tried my best to get as close to capturing the narrative voice as I could. Changing voices and employing accents always worked for me; when I read the Harry Potter books out loud to my daughters, I was constantly changing voices and accents, and my daughters’ enthusiasm for the experience helped me capture what I thought Rowling was attempting. A good audience ALWAYS made me try harder — and 12 years as an amateur actor certainly helped as well.

An interpretive reading always makes the story come alive; and it sounds like you do a great job of it!