Eaters of the Dead by Michael Crichton

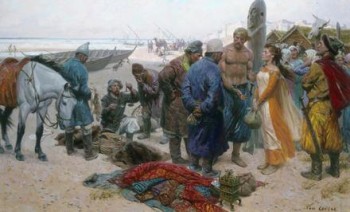

In 921 AD, Aḥmad ibn Faḍlān ibn al-ʿAbbās ibn Rāšid ibn Ḥammād was sent from Baghdad as ambassador to the Volga Bulgars (who lived in the boundaries of modern Russia) to help establish Islamic law for the newly converted nation. The short journal he kept of his travels is famous for its descriptions of the Volga Vikings, in particular the death rites of one of their chietains.

In 921 AD, Aḥmad ibn Faḍlān ibn al-ʿAbbās ibn Rāšid ibn Ḥammād was sent from Baghdad as ambassador to the Volga Bulgars (who lived in the boundaries of modern Russia) to help establish Islamic law for the newly converted nation. The short journal he kept of his travels is famous for its descriptions of the Volga Vikings, in particular the death rites of one of their chietains.

In Eaters of the Dead (1976), the fourth novel published under his own name (he’d previously released ten under pseudonyms), Michael Crichton asked two important questions: What if ibn Fadlan, during his sojourn among the Vikings, met a certain hero named Buliwyf? And what if there was a historical basis for the legend of Beowulf? His answer is a fun mix of travelogue and bloody adventure tale. Years later, it went on to serve as the basis for the The 13th Warrior, starring Antonio Banderas.

The first three chapters of Eaters of the Dead are mostly lifted straight from ibn Fadlan’s manuscript. Instead of a trusted and willing diplomat, though, Crichton recasts ibn Fadlan as reluctant traveler, forced to join the mission as punishment for his dalliance with the wife of a merchant friendly with the Caliph.

The greatest change to ibn Fadlan’s story is, of course, his fateful meeting with Buliwyf. In Crichton’s story, the Geatish Viking is present at the funeral for the chieftain. Before he can reach the Bulgars, ibn Fadlan is forced to join Buliwyf and his band. King Rothgar’s realm has been attacked by an ancient horror and he has sent one of his sons to ask the great hero for aid. Terror has come out of the mist — something so evil that the name can’t be mentioned lest it be summoned up. Later, ibn Fadlan learns they are called the wendol.

At this the old man said that I was a foreigner, and he would consent to enlighten me, and he told me this: the name of “wendol,” or “windon,” is a very ancient name, as old as any of the peoples of the North country, and it means “the black mist.” To the Northmen, this means a mist that brings, under cover of night, black fiends who murder and kill and eat the flesh of human beings.* The fiends are hairy and loathsome to touch and smell; they are fierce and cunning; they speak no language of any man and yet converse among themselves; they come with the night fog, and disappear by day — to where, no man durst follow.

Buliwyf seeks advice from a seer, the angel of death, who has a word for ibn Fadlan:

Then the angel of death, this same crone, pointed to me and made some utterance, and then she departed the hall. Now at last my interpreter spoke, and he said: “Buliwyf is called by the gods to leave this place and swiftly, putting behind him all his cares and concerns, to act as a hero to repel the menace of the North. This is fitting, and he must also take eleven warriors with him. And so, also, must he take you.”

I said that I was on a mission to the Bulgars, and must follow the instructions of my Caliph, with no delay.

“The angel of death has spoken,” my interpreter said. “The party of Buliwyf must be thirteen, and of these one must be no Northman, and so you shall be the thirteenth.”

Much against his will, ibn Fadlan is carried across southern Russian, past the city of the Bulgars, and into the great forests of the north. Finally, they arrive in the land of King Rothgar. Before they reach Rothgar’s hall they discover a destroyed farmstead. The inhabitants have all been killed, some having been gnawed on and all having had their heads taken. While this gruesome discovery overwhelms ibn Fadlan, the Vikings are unperturbed. It is only when they find a strange artifact that they seem fearful:

As we crossed the fields, Ecthgow made a discovery which was of this nature: it was a small bit of stone, smaller than a child’s fist, and it was polished and carved in crude fashion. All the warriors crowded around to examine it, I among them.

I saw it to be the torso of a pregnant female. There was no head, no arms, and no legs; only the torso with a greatly swollen belly and, above that, two pendulous swollen breasts. I accounted this creation exceedingly crude and ugly, but nothing more. Yet the Northmen were suddenly overcome and pale and tremulous; their hands shook to touch it, and finally Buliwyf flung it to the ground and shattered it with the handle of his sword, until it lay in splintered stone fragments. And then were several of the warriors sick, and purged themselves upon the ground. And the general horror was very great, to my mystification.

Ibn Fadlan gradually becomes part of Buliwyf’s party. While he never really becomes their friend, he does become their brother-in-battle. The rest of the book recounts war against the wendol in graphic, head-lopping detail.

Ibn Fadlan gradually becomes part of Buliwyf’s party. While he never really becomes their friend, he does become their brother-in-battle. The rest of the book recounts war against the wendol in graphic, head-lopping detail.

One of Crichton’s best achievments in Eaters of the Dead is his success at making the Vikings completely alien. As much to us as to the fastidous narrator, they are filthy. The chieftain’s burial involves ritualized rape and human sacrifice. Fighting and killing are constants in their society, with deadly duels breaking out in the middle of feasts. Wives are respected and not expected to remain faithful to men out traveling for months at a time. Slave women are treated as men’s common property. There’s also a great discussion of heroic deeds, when Buliwyf is called out for trying to destroy the wendol with a surprise attack. As a hero of his stature, it is expected that he take them on more directly, not with feints. Never once do the Vikings act like modern folks in furs and armor.

The least effective part of the book is the character of ibn Fadlan himself. Even as he becomes more involved with the Vikings, he remains a cipher. Oh, we learn he is an observant Muslim, trying to remain faithful in all his practices, but Crichton never provides more understanding of who he is or what moves him. I suspect this is a holdover from the original manuscript, where he attempted to be an objective observer, but it makes empathizing with him difficult.

In the end, Eaters of the Dead is worth the time. Crichton’s prose is lean and efficient, even rising to quite good at times. The man didn’t crack the bestseller lists by accident; he knew how to tell a story. The tempo builds slowly, increasing as the fictional story takes over from the historical one. At the same time, the atmosphere thickens and darkens as the struggle against the wendol becomes more desperate and bloody. When the action comes it’s cracking good. At around only 200 pages, it’s a quick, vivid read.

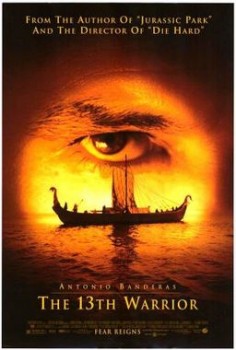

I can’t finish any discussion of this book without some words about the filmed version, The 13th Warrior (1999). Most of Crichton’s books were turned into movies pretty quickly, but for some reason it took over twenty years for this one to reach the screen. The film was initially directed by John McTiernan of Predator and Die Hard fame. Following several bad test audience reactions, he was removed from control by Crichton and the studio, Touchstone. Crichton reshot some scenes and edited out others. Ibn Fadlan was made less demonstrably devout in the final version, and the original score was replaced.

The results were a disaster and The 13th Warrior lost around 100 million dollars. The brouhaha over its failure and the bad reviews led Omar Sharif to contemplate quitting acting altogether. After a short theatrical run with little publicity, the movie faded away.

You couldn’t call the movie perfect. Most of the raw edges have been shaved off the Vikings of ibn Fadlan’s real manuscript in order to make them less unpleasant and more relatable. Presumably to make them more distinguishable from one another, Buliwyf’s men are all clad in different sorts of armor, but most is wildly anachronistic, ranging from a gladiator’s murmillo helmet (ca. 50 BC) to 15th century plate armor. Fragments of plotlines, particularly a romance between ibn Fadlan and a Northwoman, from the McTiernan version remain, unmoored and with little remaining significance. Heck, starting with Antonio Banderas as ibn Fadlan to Czech actor Vladimir Kulich as Buliwyf, there’s not a lot of racial authenticity in the casting.

You couldn’t call the movie perfect. Most of the raw edges have been shaved off the Vikings of ibn Fadlan’s real manuscript in order to make them less unpleasant and more relatable. Presumably to make them more distinguishable from one another, Buliwyf’s men are all clad in different sorts of armor, but most is wildly anachronistic, ranging from a gladiator’s murmillo helmet (ca. 50 BC) to 15th century plate armor. Fragments of plotlines, particularly a romance between ibn Fadlan and a Northwoman, from the McTiernan version remain, unmoored and with little remaining significance. Heck, starting with Antonio Banderas as ibn Fadlan to Czech actor Vladimir Kulich as Buliwyf, there’s not a lot of racial authenticity in the casting.

And I don’t care. I love this freakin’ movie. Banderas is superb, bringing considerable charm and intelligence to his role. He is no longer the docile observer of events, but an increasingly active participant. Kulich kills it as the laconic hero, as do several other members of his band. We may not come to know them in any deep way, but we easily come to feel for them as they face horror after horror with audacious bravery and boldness. Where Rothgar’s own son is a coward, more worried about a threat to his inheritance, Buliwyf and his men step willingly into the mouth of danger. It’s great stuff that never fails to stir my blood each time I watch it (which is often).

Shot in British Columbia, The 13th Warrior’s setting is one of primeval forests and mist-shrouded mountainsides. Described in the book as a magnificent, gold-covered hall, Rothgar’s Hurot is like some frontier manor built on the edge of nowhere to deliberately taunt the forces of evil. From the poisonous-looking forests that surround Hurot to the hellish caverns of the wendol, the movie looks magnificent. Technical accuracy be damned, the look is faithful to the spirit of the ancient Germanic legends set on the fringes of the civilized world in a time between myth and reality.

From book to screen, changes were made to the details of Eaters of the Dead, but not to the general tale. Ibn Fadlan is forced to accompany Buliwyf and participates in the battles against the wendol, and most of the best scenes are lifted straight from the book. What the film does is rejigger the sequence for dramatic purposes, and injects more personality into the characters. As mentioned earlier, ibn Fadlan becomes a more active participant, even solving some of the riddles about the wendol. In other words, typical movie adaptation stuff.

I’m not sure how well known The 13th Warrior is among general audiences, but among the S&S-reading crowd I know, it’s a near-totemic work of art. I would bet my life that many S&S fans of my acquaintance can recite the final speech of Buliwyf and his men as they face off against the wendol one last time. There is no film that seems as true to the heart of S&S (even if there are no magical elements in this film or book) than this movie. It gets right everything I wrote about about a few weeks ago in Why Swords & Sorcery?. If, by some strange twist of fate, you haven’t seen this movie, watch THIS, then try and tell me you don’t want to rush out and see the whole thing.

I recommend Eaters of the Dead for its fast-paced story telling and attention to recreating the past as a place of vastly different attitudes and morals. I recommend The 13th Warrior with a ludicrous amount of gusto, as one of the most exciting works of heroic adventure on film. Michael Crichton will be best remembered for his spate of techno-thrillers and the blockbuster movies made of them. For me, though, it will be for this exciting tale of heroes, reluctant and otherwise.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

I like the book, but I like the movie even more.

I enjoyed the book and movie. I love the movie toward the end when Buliwyf comes out to fight once more, a blanket falling from his shoulders. You know he’s dying, but he’s not dying in that bed. Bad guys are coming, and he’s going to use that sword as long as he can muster.

I watched this movie on DVD and thought it was excellent. Still not sure why it got such a rough ride at the box office. I knew Tiernan directed, but never realised he’d been taken off the project. Funnily enough, I remember mentioning the scene in which he learns Norse to Violette on this very site.

https://www.blackgate.com/2013/03/02/sorry-can-you-say-that-again/

Much of my senior year of college was spent reading documents written by Turkish and Arab writers during the time of the Crusades (my thesis was the Crusades as viewed through the eyes of Muslims). So when I later read Eaters of the Dead, I was impressed with how well Crichton was able to duplicate the writing style of these authors and the way they viewed the strangers to their lands, whom they called the Franj. (Based on the word Frank.) It is much like the view of the Norsemen here; as you say, they look at them as dirty, bizarre aliens.

The primary author for this period was Usama ibn Munqidh, an Arab diplomat who wrote extensively of the period in his Kitab al-I’tibar. I spent some long hours writing notes on this document during one bleak winter term in Minnesota.

I appreciate the movie strictly because of the great score by Jerry Goldsmith, one of his last.

Thanks for this review. I’ve been curious about this book for some time, but I once tried to read the one about time traveling moderns in medieval suits of armor (can’t remember the name of that one right now) and was scared away from Crichton overall. Like everyone here, though, I love the movie! It would be interesting to know what McTiernan’s vision was and understand why others felt it had to be corrected.

Skoal! Yes, I, too, love this movie. There are the anachronisms, the abandoned plot thread of the scheming son, which just vanishes, and the mostly abandoned thread of the love interest. Usually this would drive me crazy but… I love this anyway. So many grand brave heroic moments. We may not even know the names of most of the Viking characters, even the witty, charming one that’s probably my second favorite, but we get to know and like them and root for them.

There’s that grand death scene with Buliwyf, which has few if any equals in sword-and-sorcery/heroic fantasy on film. And then there’s that prayer/code which is just genius, and really has no equal in heroic fiction on the page or the cinema.

You’re damned well right I have it memorized! “Lo, there do I see my father. Lo, there do I see my mother and my sisters and my brothers. Lo, there do I see the line of my people, back to the beginning. Lo, they do call to me. They bid me take my place among them in the Halls of Valhalla, where the brave may live forever!”

I love this movie so hard that I swiped the Viking prayer, modified from its original form given in Ibn Fadlan’s manuscript, for a scene in A Gathering of Ravens . . .

@Bill C. – Pretty much the same for me

@Matthew W. – Good lord, does this movie hit all the right notes with scenes like that one

@Aonghus F. – It’s got serious flaws as a movie, but considering the junk that makes big bucks or gets critical adulation, it doesn’t make sense.

@Ryan H. – I’m tempted to buy Ibn Fadlan and the Land of Darkness: Arab Travellers in the Far North to read the complete original account. Goldsmith’s score is indeed very good, but what I’ve heard of the original by Graeme Revell is good too

@Ryan H. – That was Timeline. His techno-thrillers tend to be more than a little didactic and simplistic. This is the only book of his I’ve ever really liked

@Howard – I suspected you might be someone who’d know that speech. Yeah, all the film’s problems fade away against the power and heroism of Buliwyf, ibn Fadlan, and company.

Thanks for the great review. And great comments by everyone. I haven’t read the book, but can only agree about how incredibly entertaining the movie is. A movie can be unauthentic historically (most of them are), but have an authentic soul, and this one does.

I love the movie, and the book is one of my favorite Crichton novels along with Pirate Latitudes and The Great Train Robbery.

I love the movie (thanks in large part to Kulich’s and Storhoi’s performances), but not the last battle. The immediate lead-up and aftermath, yes, but not the battle. Unlike the other battles, it’s pretty much just the heroes killing bad guys. I thought it was one of the weakest scenes in the movie.

@Scott O. – And why wouldn’t you, it’s actually deserves to be called awesome.

@Robert Z. – The book’s worth a spin (and it’s short enough to read a in day). Yeah, historicity has its place, but here, you’re absolutely right to say the film’s got an authentic soul.

@CMR – I’m curious about the Great Train Robbery having loved the movie.

@Jeff S. – Kulich and Storhoi are perfect. Rewatching it the other night, I have to agree. The final battle is pretty weak sauce, especially after the first night battle and the running cave fight. There’s real tension in those other sequences that’s lacking to the same degree in the finale. Also, it feels drastically truncated, a victim of Crichton’s editing.

I would have commented sooner, but I had some password issues!

Man, I thought I was one of the only people who liked “13th Warrior”! Glad to see that I’m not alone.

I read “Eaters of the Dead” a couple of years before “13th” came out and I remember really liking the book. I agree that one of the things that makes it work is the alien-ness and backwardness of the Norsemen, which is viewed through Ibn Fadlan’s eyes– and he is also a bit alien to the sensibility of modern readers. They do become comrades in arms, and that’s part of what makes it work.

That said, I don’t know if one could follow multiple adventures of the Norsemen– part of the punch of the story is the temporary nature of the alliance between Fadlan and the Norsemen. If I remember, Chrichton left it open for further adventures of Ibn Fadlan.

As to the final battle scene in the movie, I seem to recall that it one of the few occasions when the Norsemen do the sensible thing– all they have do, all they’ve had to do this whole time– is find and defeat the war chief of the Wendol (I can’t remember if he there is a certain way they have to beat him or not…); which I thought was a strange parallel between the ways that the Norsemen are stuck in (to Fadlan’s view) a morass of tradition and superstition, so are the Wendol.

The sensible thing for Buliwyf to do is to kill the Wendol in an ambush– but his culture won’t allow it. The sensible thing for the Wendol to do is destroy all the people of Hrothgar’s holding, with or without their holy leader, but that is just the way their culture (or maybe even their minds) work.

I enjoyed the movie a lot. In fact, I’ve seen it a couple of times. It’s one of those movies I revisit every now and again. It captured a unique tone for me that I have yet to find in another flick. The movie made me buy the book because I only discovered after the fact that it was based on a Crichton story, which again, was based on that old manuscript, or partly anyway.

The history behind the manuscript is interesting. I found Ahmad ibn Fadlan’s descriptions of the Vikings fascinating.

Cheers for the review. It was an excellent reminder.