Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Pellucidar Saga: At the Earth’s Core

Once upon a time, I shouldered the enjoyable burden of analyzing all of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Venus (Amtor) novels. Then, to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the publication of A Princess of Mars, I took on the same task for the Mars (Barsoom) novels. It was inevitable that I would one day bring the same survey methods to the Pellucidar novels at the center of the earth. (Sorry, a Tarzan series just won’t happen. There are far too many Tarzan novels for the sanity of even the most hardcore ERB fan to take in concentrated doses.)

Once upon a time, I shouldered the enjoyable burden of analyzing all of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Venus (Amtor) novels. Then, to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the publication of A Princess of Mars, I took on the same task for the Mars (Barsoom) novels. It was inevitable that I would one day bring the same survey methods to the Pellucidar novels at the center of the earth. (Sorry, a Tarzan series just won’t happen. There are far too many Tarzan novels for the sanity of even the most hardcore ERB fan to take in concentrated doses.)

Our Saga: Beneath our feet lies a realm beyond the most vivid daydreams of the fantastic… Pellucidar. A subterranean world formed along the concave curve inside the earth’s crust, surrounding an eternally stationary sun that eliminates the concept of time. A land of savage humanoids, fierce beasts, and reptilian overlords, Pellucidar is the weird stage for adventurers from the topside layer — including a certain Lord Greystoke. The series consists of six novels, one which crosses over with the Tarzan series, plus a volume of linked novellas, published between 1914 and 1963.

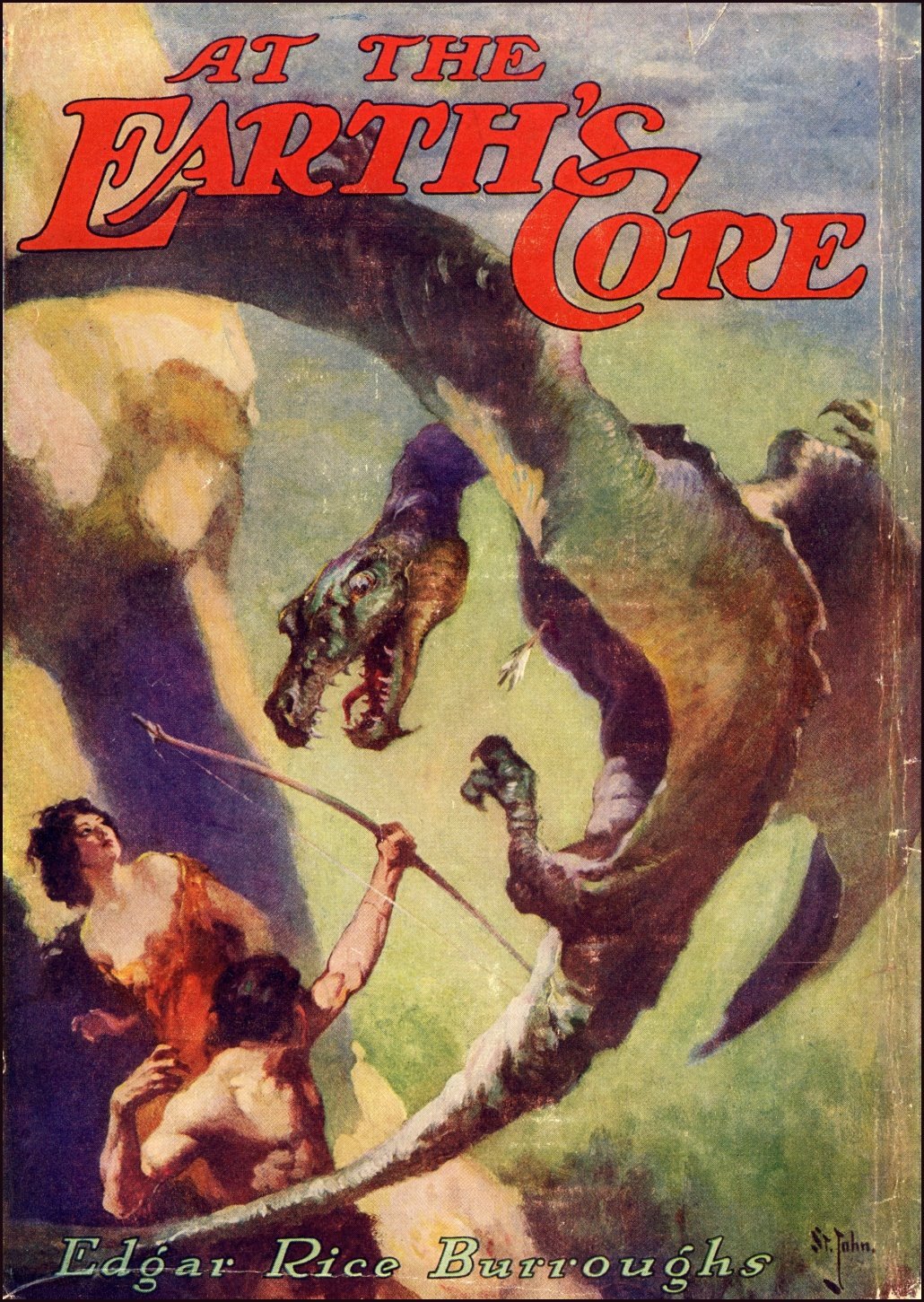

Today’s Installment: At the Earth’s Core (1914)

The Backstory

Subterranean realms of the fantastic have a history reaching back to antiquity. But it was the nineteenth-century speculative theories of Captain John Cleves Symmes about the hollow earth that ignited a wave of fictional explorations of What Lies Within: “I declare the earth is hollow, and habitable within; containing a number of solid concentrick [sic] spheres.”

Symmes picked up from Edmund Halley’s seventeenth-century hypothesis of a series of nested shells inside the earth, but proposed only a single sphere with a “sun” at the center that made the interior surface habitable. Symmes’s theory garnered a few adherents, and even suggestions of organizing expeditions to the poles to locate the openings that accessed the inner world.

But by the second half of the nineteenth century, Symmes’s ideas were abandoned as having zero scientific proof, so it fell to the field of the evolving scientific romance to make the best use of the hollow earth. The most famous example is Verne’s A Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864), which ignores Symmes’s inner shell for a vision that contemporary science might support. Verne still put prehistoric beasts in his subterranean land, for which we’re all grateful. There are numerous other Victorian hollow earth tales, most of which are only read by speculative fiction historians today: The Goddess of Atvatabar by William R. Bradshaw (1891), The Secret of the Earth by Charles Willing Beale (1899), the feminist utopian novel Mizora by Mary E. Bradley Lane (1881), and Etidorhpa by John Uri Lloyd (1895).

Enter Mr. Burroughs of Chicago. In 1913 he was in the middle of a furious creative period. Empowered by the success of A Princess of Mars and Tarzan of the Apes, he turned out new work at a blistering pace. At the beginning of the year he completed the first Tarzan sequel, and from January to July wrote The Cave Girl, The Warlord of Mars, and the short novel originally titled “The Inner World.”

“The Inner World” originated from the suggestion of editor John S. Phillips at the American Magazine, a more prestigious publication than Burroughs’s standard pulp markets. Phillips wanted an imaginative story from ERB, but not one featuring either Tarzan or Mars. The author plucked up Symmes’s discarded theory, gave it his special world-building treatment, and produced a setting stranger than anything he’d yet crafted. To meet the magazine’s requirements, Burroughs kept the length under 30,000 words. But Phillips wasn’t clear on what he expected — he probably was never serious about accepting anything from ERB — and turned down the story as too “unbridled.” Huh. If you aren’t looking for an unbridled story, don’t ask Edgar Burroughs to write it.

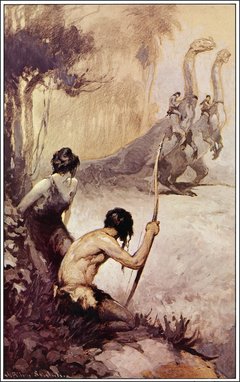

Ed must have known rejection was imminent, since in an earlier letter to Phillips he mentioned that the story “is so wildly ridiculous that I am quite sure you would not care for it.” He turned to his dependable pulp magazine market, and Thomas Newell Metcalf at Munsey Magazines agreed to purchase “The Inner World” if Burroughs expanded it to novel length with additional material about what Metcalf called “the peculiar over-sensitized lizards.” Ed complied, and the retitled At the Earth’s Core appeared in four installments in All-Story Weekly during April 1914. The first book edition was published by A. C. McClurg in 1922 with cover art and illustrations by J. Allen St. John.

The Story

The Story

“In the first place please bear in mind that I do not expect you to believe this story…”

So begins another frame narration from the most frequently recurring of all Edgar Rice Burroughs characters: a fictional version of himself. Pseudo-ERB is around for only a few pages, enough time to meet hero David Innes wandering the Sahara. Innes is shocked to learn that ten years have passed since the beginning of the adventure he now relates.

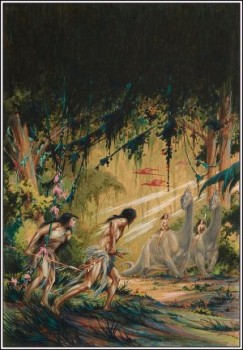

Innes, heir to a prosperous Connecticut mine, invests money in a drilling machine invented by Abner Perry, a geological engineer with interest in paleontology. (Wonder if that will come in handy at some point?) Perry’s “Iron Mole” is designed to carry passengers on deep-boring expeditions. Perry and Innes give the borer a test run, which goes spectacularly wrong and locks the Iron Mole on a trip straight down. Hours later, the drill breaks through to Pellucidar, the world on the inner curve of the earth’s crust, where no horizon exists and the sun is a sphere of fire that hangs forever at high noon. There’s also a slew of bizarre, dangerous megafauna that immediately want to kill Perry and Innes. Cave bears, giant tigers, an assortment of dinosaurs, and so forth. Thank you so much, divergent evolution.

The two upper-worlders end up in the clutches of the gorilla-like Sagoths, a race serving the reptilian masters of Pellucidar, the sixth-sense using Mahars. The Mahars enslave the human tribes of Pellucidar and occasionally eat them. Among the other human captives, Innes falls for Dian the Beautiful of the ruling class of the land of Amoz. But Hooja the Sly One has his designs on Dian, and steals her away during the forced march into the Mahar city of Phutra. Perry discovers that the Mahars are all female and use a special chemical to reproduce without males. If Perry and Innes can get hold of this chemical formula, they may be able to defeat the tyrants of Pellucidar.

As Innes adventures through Mahar underground cities and among the tribes of Pellucidar, he must also battle for Dian’s affections against the pursuit of the scarred Jubal the Ugly One and the scheming of Hooja the Sly One. But even worse for his romantic chances is an accidental insult he gives to Dian that repels her. Innes keeps his mind off his romance problems with fights against numerous monsters, forging alliances with men such as Ja of the Mezop people, and obtaining the Great Secret of the Mahar.

Just when it appears as if David Innes will successfully lead the humans of Pellucidar in rebellion against the Mahars and make himself emperor of the inner world, a trip back to the surface world to fetch supplies goes amiss. The pseudo-ERB leaves us in suspense of further reports from David Innes.

The Positives

The Positives

Edgar Rice Burroughs circa 1912–15 was on fire. This is the eon of The Gods of Mars, The Warlord of Mars, The Return of Tarzan, and The Mucker. There was an occasional misstep, such as The Outlaw of Torn, when Burroughs wasn’t yet certain of his writer’s blood-type. But from Tarzan of the Apes on, Ed was on a wild tear of pulp brilliance. At the Earth’s Core is one of the gleaming jewels of this epoch. It ranks among the handful of early SF masterpieces that enthusiasts can read over and over again to relive the thrill of limitless adventure that reaches levels of the sublime. It is quintessential Burroughs.

The imaginative qualities of At the Earth’s Core are the major source of its appeal. But what immediately stands out is the pacing. This sucker moves. Burroughs rapidly learned to strip the fat from his earlier experiments. At the opening of Chapter I, David Innes introduces himself. A page later, he’s met Abner Perry and they board the Iron Mole. At the end of Chapter I, they arrive in Pellucidar. After a few moments to deduce the strange nature of the place, they’re attacked by a giant sloth-bear-elephant (dyryth), and arboreal humanoids capture David as Chapter II closes. And Chapter III has an arena fight.

This ought to give a sense of how the book is paced. Burroughs has leaped past the slow exploration of early scientific romances and draws a straight line from the ordinary to the extraordinary. There are no lengthy voyages to polar entrances or descents into volcanoes with extensive breaks for travelogue passages; Perry and Innes burrow to the good stuff in mere pages. Try to imagine how H. Rider Haggard might have handled this same set-up: the prologue in the Sahara would’ve consumed three chapters just to find Innes. This is no slight on Haggard, but a comparison to show how much Burroughs changed the way we think of pacing in adventure stories. The daydream adventure is now a delirious hallucination. A hallucination you don’t mind having.

The rhino-charge pace may partially be the result of the manner of how ERB wrote At the Earth’s Core. Starting out as a 30,000-word novella, which was then expanded with more details, the book retains that swift sensation of a shorter work. Since the added stretch, from Innes’s escape and then return to Phutra, contains the best sequence in the book, it doesn’t slow the action at all. The one place where Burroughs does allow the book to take a breath is a pellucid (heh) scene in an Edenic valley that arrives at the right point in the action and doesn’t overstay its welcome.

Although Burroughs wasn’t the pioneer of the subterranean fantasy/scientific romance, his take on the concept is remarkable for its blending of science into science fantasy. It’s almost as if no one else had touched the idea before. Pellucidar feels concurrently a real place and a dream. The picture of the inner world forms rapidly with the various tribes and their homelands, the Mahar underground city, the Sagoth hordes, a cornucopia of unusual creatures with exotic names, and attention paid to individual cultural practices. (I particularly like the way the Mezop people create complex broken trails that take an immense effort to follow because the time to traverse them doesn’t matter in timeless Pellucidar.) There’s also seeding for future ideas that create an even greater expanse of the setting, such as the mention of the Dead World, The Land of the Awful Shadow, and the Mountain of the Clouds.

However, two ideas dominate Pellucidar as a setting that make it stand out, and these are also the ideas that give it a hallucinatory quality: the concave curvature of the land that erases the horizon, and the lack of meaningful time. The zero-horizon is a simple but effective visual tool that Burroughs keeps present just enough to remind readers that Innes and Perry aren’t stomping around a standard Lost World. The time distortion, however, becomes the novel’s great conceit. The sun locked at high noon explains only part of the timelessness; Pellucidar seems to have no time anywhere, even underground. What might be a basic detail — it’s always noon! — becomes a net cast over the whole book. As Ja explains to Innes, “time is no factor where time does not exist.”

However, two ideas dominate Pellucidar as a setting that make it stand out, and these are also the ideas that give it a hallucinatory quality: the concave curvature of the land that erases the horizon, and the lack of meaningful time. The zero-horizon is a simple but effective visual tool that Burroughs keeps present just enough to remind readers that Innes and Perry aren’t stomping around a standard Lost World. The time distortion, however, becomes the novel’s great conceit. The sun locked at high noon explains only part of the timelessness; Pellucidar seems to have no time anywhere, even underground. What might be a basic detail — it’s always noon! — becomes a net cast over the whole book. As Ja explains to Innes, “time is no factor where time does not exist.”

Since At the Earth’s Core is at heart an adventure novel and not a meditation on time, it needs some adversaries — and wow does it deliver. Jubal the Ugly provides a fine grotesque, and his duel to the death with Innes over Dian is the action finale of the book. Hooja the Sly One is a villain type that ERB took great pleasure writing: the greasy little sneak. Most of Burroughs’s best bad guys fit this type, and it was one of the joys of the recent movie The Legend of Tarzan that Christoph Waltz played a sleazeball cast in the same mold. Hooja is the main motivator of the final quarter of the novel, where he betrays Innes, Perry, and their ally Ghak the Hairy One at a key moment. Hooja also yanks victory away from Innes in the uncanny coda when he again steals away Dian and leaves Innes with a Mahar for a companion on the trip back to the surface.

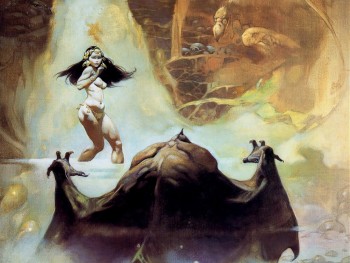

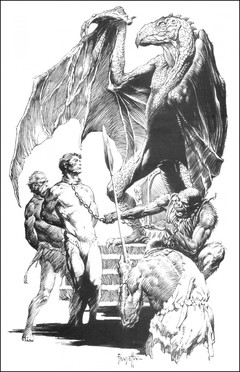

The huge villain success of At the Earth’s Core is, of course, the Mahars — those “peculiar over-sensitized lizards.” The Mahars are among the best alien creatures to appear in the Burroughs canon and one of his greatest creations, period. Abner Perry describes the Mahars as resembling an evolution of Rhamphorhynchus into an eight-foot long aerial and aquatic reptile of immense mental capacity. The Mahars communicate through something odder than telepathy; according to Perry, they “project their thoughts into the fourth dimension where they become appreciable to the sixth sense of the listener.” No, it doesn’t make scientific sense, but it sounds incredible.

The most intense moment with the Mahars is also one of the book’s most chilling and memorable, and among the most shocking sequences of Burroughs’s career. David Innes watches a ritual ceremony in a Mahar temple, where the Mahar queen swims in a pool around small atolls crammed with human slaves. The queen hypnotically lures a slave woman into the shallows, leading her into and out of the water — and taking away one limb at a time from the mesmerized woman. The other Mahars join in and consume all the slave women and children, and the Mahars’ lesser servants, the thipdars (pterodactyl-like creatures), dive down upon the remaining men and pick them away to bones. This is probably one of the additions ERB made to the shorter version for pulp publication: it isn’t wholly necessary to the story, but the indelible impression it makes elevates the book.

When Innes first plans to kill a Mahar to escape from their city, Abner Perry objects based on his religious and scientific convictions: he can’t condone murder, and in his view the Mahars are not monsters. “Here they are the dominant race — we are the ‘monsters’ — the lower orders. In Pellucidar evolution has progressed along different lines than upon the outer earth… We see here what might have well occurred in our own history had conditions been what they have been here.”

However, Perry rapidly turns toward Innes’s plan of the conquest of Pellucidar and the overthrow of the Mahars. It doesn’t take much, only encouraging Perry to think that god brought the two of them here for the purpose of leading the humans of the inner world “to the light of His mercy while we’re training their hearts and hands in the ways of culture and civilization.” David Innes doesn’t take Perry’s religious colonialism seriously, since he habitually scoffs at Perry’s penchant for prayer. What motivates Innes is the desire of conquest and fashioning the humans of Pellucidar into warriors. (Even his love for Dian feels puny at these points in the story.) This creates a fascinating clash of early twentieth-century imperial imperatives. These battling ideas of science, religion, and contemporary politics are what gives Burroughs’s work such enduring interest. At his best, ERB always offers the reader something to ponder among adventuring — even if the reader doesn’t agree with the ideas advanced.

However, Perry rapidly turns toward Innes’s plan of the conquest of Pellucidar and the overthrow of the Mahars. It doesn’t take much, only encouraging Perry to think that god brought the two of them here for the purpose of leading the humans of the inner world “to the light of His mercy while we’re training their hearts and hands in the ways of culture and civilization.” David Innes doesn’t take Perry’s religious colonialism seriously, since he habitually scoffs at Perry’s penchant for prayer. What motivates Innes is the desire of conquest and fashioning the humans of Pellucidar into warriors. (Even his love for Dian feels puny at these points in the story.) This creates a fascinating clash of early twentieth-century imperial imperatives. These battling ideas of science, religion, and contemporary politics are what gives Burroughs’s work such enduring interest. At his best, ERB always offers the reader something to ponder among adventuring — even if the reader doesn’t agree with the ideas advanced.

There are elements of psychological shading in David Innes that belie his nominal role as the stalwart athletic hero. He shows introspection when he’s caught on his own in Pellucidar, turning philosophic about human insignificance. This isn’t something you’d hear from John Carter, nor is it like Tarzan’s own internal musings. Only in a few places does the future colonial conqueror David Innes materialize, such as his imaginings (which he paradoxically denies) of how he’ll appear as a savior to the future human generations because of his destruction of the Mahar, and his late decision to appoint himself the emperor of a new Pellucidar after the fall of the reptilian despots. But this is mostly sequel set-up; within the confines of At the Earth’s Core, Innes is one of the more human-scale of ERB’s early heroes.

Modern critical opinion of Edgar Rice Burroughs allows him great imagination, but doesn’t offer the same generosity to his writing style. Yet in his finest books Burroughs could craft stunning passages that sing with Romanticism and the vastness of the possible. At the Earth’s Core, set in a dream-like land without time or edges, is powerfully suited for beautiful writing:

The fascination of speculation was strong upon me. It was as though I had been carried back to the birth time of our own outer world to look upon its lands and seas ages before man had traversed either. Here was a new world, all untouched. It called to me to explore it. I was dreaming of the excitement and adventure which lay before us could Perry and I but escape the Mahars when something, a slight noise I imagine, drew my attention behind me.

As I turned, romance, adventure, and discovery in the abstract took wing before the terrible embodiment of all three in concrete form that I beheld advancing upon me…

The second paragraph is as perfect an encapsulation of ERB as I can imagine: romance, adventure, discovery — and how it rapidly turns to fear and danger (and excitement).

The Negatives

The Negatives

It is possible for a book to move too fast, and At the Earth’s Core accelerates from standard narrative into near-synopsis after Innes defeats Jubal and resolves the romance conflict with Dian. The building of the alliance of the human tribes into a warring force against the Mahars, their first armed combat, and Innes’s decision to return to the surface arrive so fast that it seems Burroughs was simply over-eager to get to his planned sequel. Thankfully, the sequel arrived soon.

Innes pursuing Dian the Beautiful is the least interesting part of At the Earth’s Core because it’s so much ERB business-as-usual. In one of the author’s standard clichés, a basic misunderstanding between hero and heroine early on separates them to provide an artificial barrier against romance — and the way they finally solve it isn’t one that modern readers will particularly like. With the fight against the Mahars taking such prominence, the Dian-Innes romance becomes easy to file away. In fact, that’s pretty much what Burroughs does; when Dian pops up in the hidden valley near the end in a conventional ERB super-coincidence, it’s a surprise because that plot strand was almost buried by that point.

The rewrite that added the lengthy middle section does have one negative effect in what’s otherwise a seamless addition: there’s a significant gap between Perry’s first suggestion of obtaining the Mahars’ formula for asexual reproduction and the point when Innes goes after it. So much occurs between these points that it’s possible for readers to have lost track of this goal until Innes returns to Phutra. Burroughs also allowed a gaffe to slip in because of the rewrite: Innes first sees the thipdars, the pterodactyl servants of the Mahars, during the grotesque aquatic sequence at the temple. But many chapters later when Innes saves Dian from a thipdar, he claims it’s the first time he’s ever seen one.

Burroughs was skilled at making silly science sound logical, but the time distortion of Pellucidar creates baffling moments for readers who think about it beyond the dream-surface. The human body has its own internal rhythms, such as hunger and the need for sleep. And if the position of the sun is the prime reason for Pellucidar’s hazy sense of chronology, why does it also apply in the underground Mahar cities? These questions can’t harm how well the time device works overall, but the questions remain.

It’s odd to talk about stretching credulity in a book set in the inner world with fourth-dimensional dinosaur tyrants and a grab-bag of other weirdness. But Innes, Perry, and Ghak using the Mahar skins as effective disguises really is stretching it. It does set up the other credulity-stretching moment, which is the clunky swapping of Dian for a Mahar in the twist ending: somehow, David Innes cannot tell that the person sitting next to him in the Iron Mole under the cave lion skin isn’t his beloved Dian but a large winged super-reptile. It’s another side-effect of the rushed closing chapter.

ERB characters often have the ability to learn alien languages swiftly. But the speed that Innes learns to fully converse with Dian and the other tribes borders on superhuman. This could be explained away as the elastic movement of time — but there are limits to what even that conceit allows.

Craziest Bit of Burroughsian Writing: The passage is too lengthy to quote here, but David Innes attributes his defeat of a hyaenodon with a hurled rock to his prowess as a baseball pitcher, complete with a play-by-play of the wind-up and winning pitch.

Most Inventive Idea: Everything, really, but the chrono-distortion is the most cerebral concept and gives Pellucidar its peculiar quality. But I could have easily nominated the Mahars’ fourth-dimensional communications, or the Pellucidarian homing sense, or the nature of Mahar reproduction, or the Mezop broken pathways, or…

Best Creature: The Mahars, no contest.

David Innes, Secular Humanist: “In between [Perry] often found excuses to pray even when the provocation seemed far-fetched to my worldly eyes — now that he was about to die I felt positive that I should witness a perfect orgy of prayer — if one may allude with such a simile to so solemn an act.” The kicker is that, rather than praying, Perry ends up swearing at the malfunctioning machinery.

Carson Napier Pre-Memorial Foolishness Award: David Innes’s failure to notice that his girlfriend sitting beside him is actually a winged eight-foot dinosaur. I don’t think a simple animal skin cloak can make that ideal a disguise.

How about a sequel? There’s too much unfinished business for there not to be one. Clearly, Ed planned a sequel from the start, so go for it. Plus, I’d like to visit the Land of the Awful Shadow. That’s something we’re clearly meant to experience.

Next: At the Earth’s Core — The Movie! — and then Pellucidar.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Godzilla on interviews.

Yet another Burroughs series I need to reread one of these days.

Maybe at some point just a partial Tarzan series? As with all Burroughs, it kind of runs out of steam about 2/3 of the way through; it’s just that with Tarzan, that 2/3 point happens at book 16 or 17 instead of book 9 or 4.

@Joe – I’m going to try to do something with the Tarzan novels, but I’m not sure quite what yet. One idea was to do a “Tarzan Swing-By” and just pick novels here and there. Because I’ll be writing about Tarzan at the Earth’s Core, I thought I might take a look at the book that precedes it, Tarzan and the Lost Empire.

Wow a Ryan Harvey article! Long time no see!

It is good to see you back here on Black Gate.

@Glenn & Ape – Thanks! The whole “sabbatical” was just something that wasn’t under my control involving moving and a new job, and blah blah real world stuff. But after John won the World Fantasy Award and personally thanked me when he accepted it, I realized I had an obligation to this website, an obligation to John, and that I just missed writing about Edgar Rice Burroughs so much.

Never warmed up to David Innes like I did with John Carter or even the Apache Devil but have fond memories of the middle books.

If you do Tarzan would be interested in your thoughts on Tarzan and the City of Gold. It was the first ‘real’ Tarzan novel I read as a young pre-teen way back in the early ’60s> (We had the Tarzan and the Lost Safari book as kids and being young took me a bit to realize who Burroughs was but made up for it big time when the Ace/Ballentine books began appearing. To this day was never quite sure what was on Tarzan’s mind regarding Nemone and wished Burroughs had given La a happy future.

I hope to see some movie reviews too. Post them when you can. I would love to hear your commentary on the future Godzilla versus King Kong remake. The new Zilla is pretty cool but my money is still on the monkey. It’s a family thing you know?

@Ape – I think this is a “Whoever Wins, We Win” situation. I’ll have to wait and see how Skull Island shakes out and what I think of that Kong (trailer looks amazing though). And there are some movie reviews coming up. I’ve got the John Carpenter series going, and I’m also going to look at some little-known sword-and-sandal movies.

[…] Ryan Harvey on At the Earth’s Core at Black Gate. […]

The ritual feeding sequence by the Mahars in the temple is chilling. I know ERB can write dark stuff but that sequence made me wish he had written some straight horror stories.