The Limits of Wargaming #2: Betrayals, Surprises and Strategic Advantage

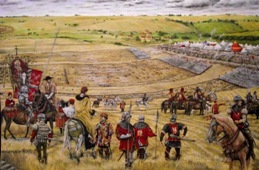

10th July 1460, near Northampton, England. Battle of Northampton. It’s the Wars of the Roses. King Henry VI — well His Grace’s advisers, anyway — the Lancastrians, if you must — versus the Yorkists led in this case by the Earl of Warwick .

The King’s forces have fortified themselves into a bend in the river.

They’ve got a ditch, wooden stakes, perhaps carts, certainly cannon. They’re gearing up for a rerun of the Battle of Castillon (an English defeat so utterly embarrassing that the swords of fallen English men-at-arms are a scholarly category in their own right!)

Warwick’s men advance into a hail of armour-piercing arrows, cannon balls and crossbow bolts. It looks as if he’s going to try to grind through the defences — the battle will be down to killing power and morale.

Except it doesn’t turn out that way.

As soon as the vanguard reaches the defences, Lord Grey, leader of one of the defending units, displays the Warwick bear-and-ragged-staff flag and has men change sides. They even help their new mates through the defences.

The rest is History, which is to say ugly and nasty.

The Lancastrians break and rout into the shallow river where they trample each other into a mass drowning. The Lancastrian leaders get cut down — nasty things civil wars; not much chance of a ransom.

So here we have a battle that would have been boring to wargame using authentic tactics — essentially a test of your army list — that actually turns on a betrayal motivated by off-table politics. Presumably Lord Grey was always going to change sides, so the Lancastrians had lost the battle before the first arrow was loosed.

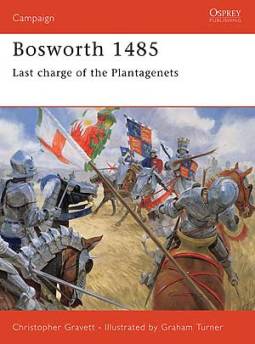

In-battle betrayals are really common in civil wars, another classic being the Battle of Bosworth where the Percies of Northumberland sat tight and let King Richard III lose, and the Stanleys changed sides and ruined what would otherwise have been the coolest cavalry charge in history.

How would you model betrayals in a wargame scenario, or include the possibility in a rule set?

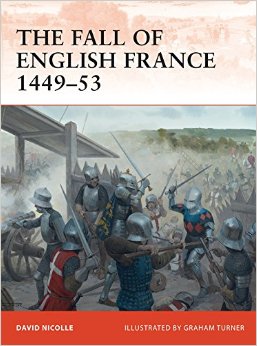

Now, did I mention the Battle of Castillon? That’s an example of something else…. a bit like those stories of drivers driving off piers into rivers because they are too busy looking at their GPS to notice there is no road.

1453, dog end of the Hundred Years War between England and France. John Talbot, 70-something English commander is trying to break the French siege of the little town of Castillon. He also wants to give the French a drubbing, so when dust rises from the French camp, he takes this as evidence that they are retreating, and hurls his little army at them before they can run away.

It turns out that the French are not running away. That dust was just them sending their horses and servants to the rear.

It also turns out that “camp” really means “fortified artillery park”.

I’m wincing as I type this.

Some of my ancestors were — possibly — English archers (there’s a database of English medieval soldiers where you search on your surname). We English (yes, I’m also Scottish… identity is complex) take a certain guilty pride in the Hundred Years War, in tales of Good King Henry and the mighty-thewed yeoman archers. I’ve also handled a rusted sword from the battle, felt the likely edge damage, and perhaps caught a whiff of sweat and terror and black powder carried on the winds of time.

And the English fight magnificently. Some of them even get through the barriers and come to blows with the French before they are killed or captured.

But Game Over for the English in France.

Military History is full of surprises like this.

Commanders walk into army-sized ambushes, or blunder into battles with much larger forces. They also misjudge situations horribly. Most of the crusades of St Louis fall into this category, the comedy apogee being the moment when the crusaders wonder why the Egyptians won’t leave the higher ground, and then the Nile floods…

Finally we come to what I’ve called strategic advantage. Some armies are just doomed out of the box because the enemy has the advantage of men, material, and reinforcements… like the Albigensians defending Beziers against Simon de Monfort’s “crusaders” — Kill them all! God will know His own! — or the tiny Lancastrian forces defending the unwalled town of St Albans against the much larger Yorkist army.

Yes, there’s the possibility of tactics and hard fighting prevailing, but you’d really need a leader with the generalship of Alexander and the prowess of Conan.

And luck.

Lots of it. Because, mostly you end up with glorious failures like Richard III’s flanking charge at Bosworth.

So, I think many decisive Medieval battles hinge on betrayals, surprises and strategic advantage. In each case, the battle is pretty much decided before it starts, and the fighting is just a test of decisions made much earlier.

You could model all of these using wargame rules, but would any of them be interesting to play?

M Harold Page is the Scottish author of works such as Swords vs Tanks (Charles Stross: “Holy ****!”). For his take on writing, read Storyteller Tools: Outline from vision to finished novel without losing the magic. (Ken MacLeod: “…very useful in getting from ideas etc to plot and story.” Hannu Rajaniemi: “…find myself to coming back to [this] book in the early stages.”)

One possibility for Betrayals is to set a Victory Point threshold and have a unit or commander switch sides if/when the “winning” side moves above the threshold, and switch back if the VP score (or differential) drops below. So, there would be an incentive to run up the score early and trigger a betrayal, against the problem of overextending forces/resources and losing both the betrayers and maybe the game.

The Bosworth story reminds me of an 80’s William F Wu story, where battles are fought between wargamers on a PC. The Bosworth battle that is described in the story has a random probability of the Stanleys’ betrayal.

And in that story, as I recall, the cavalry charge *works*.

If the test of decisions made much earlier involves decisions that were questionable, they still might be interesting to play.

@Eugene: You could certainly model it using “twist cards”. Part of the fun would be working out what card the opponent had from the way they deployed their forces.

@Princejvstin: I think the Stanleys just wanted to strike the winning blow and hence earn gratitude from the winner.

@Sarah Avery: Yes to an extent. There’s probably an acceptable ratio between setup time and playing time.