Space Colonies, Interstellar Fleets, and The Martian in the Attic: The Best of Frederik Pohl

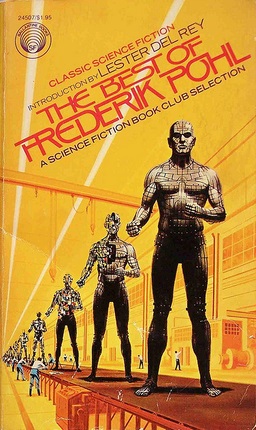

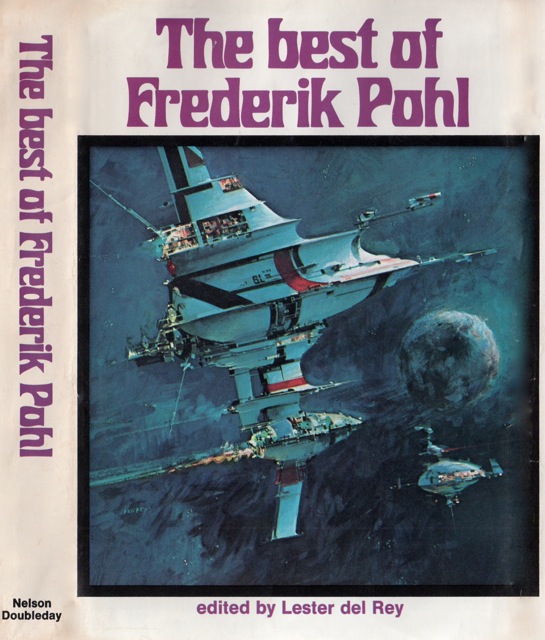

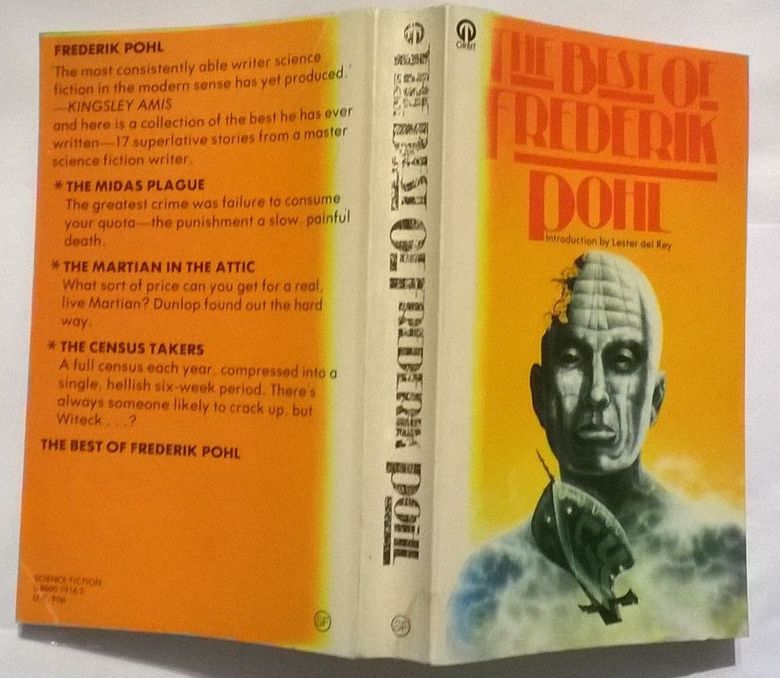

In my continuing posts of Del Rey’s Classic Science Fiction Series, we now come to the third volume in the series, The Best of Frederik Pohl (1975). The introduction was done by none other than the writer and editor Lester del Rey himself (1915-1993). As with The Best of Stanley Weinbaum and The Best of Fritz Leiber, the cover art for Pohl’s volume was done by Dean Ellis (1920-2009). And as with Leiber’s volume, the author himself, Frederik Pohl (1919-2013), gives an afterword as well commenting on several of the stories within.

In my continuing posts of Del Rey’s Classic Science Fiction Series, we now come to the third volume in the series, The Best of Frederik Pohl (1975). The introduction was done by none other than the writer and editor Lester del Rey himself (1915-1993). As with The Best of Stanley Weinbaum and The Best of Fritz Leiber, the cover art for Pohl’s volume was done by Dean Ellis (1920-2009). And as with Leiber’s volume, the author himself, Frederik Pohl (1919-2013), gives an afterword as well commenting on several of the stories within.

To call Pohl a giant of science fiction is a cliched understatement. Pohl wrote and edited science fiction for over seventy years. He won numerous awards and was editor for many years of Galaxy and If magazines. His mark on science fiction is absolutely indelible.

But, I have to admit, I had actually never read any of Pohl’s stories before this volume. So I came to The Best of Frederik Pohl with fairly neutral eyes, though expecting to read some great classic science fiction. What did I find? Let me comment on a few the stories in this volume that really struck me and then I’ll give some final overall thoughts on Pohl’s work.

The story “Happy Birthday, Dear Jesus” was a fairly on-the-nose satire against Christmas commercialism — a pretty easy target. But, surprisingly, this satire was set within the context of a love story about a department store manager seeking to marry the daughter of a very conservative missionary. Not what I was expecting. What was even more surprising was that this turned out to be a very heart-stirring little romantic tale, very unexpected given the cynical bite of the story’s overall point.

Interestingly, in retrospect, the sci-fi elements of this story seem fairly tangential now. In fact, I don’t remember exactly what the sci-fi elements in this story were. And this wasn’t the only story like this. I often found myself trying to remember exactly what made Pohl’s stories examples of science fiction. I’ll return to this point.

Pohl’s story “Father of the Stars” fit more with what I was expecting from a classic sci-fi tale. Take a look at this excerpt, also exhibiting Pohl’s excellent prose:

[Norman Marchand] had raised money. A very great deal of money. He had taken all of the money he had begged and teased out of the pockets of the world and used it to finance the building of twenty-six great ships, each the size of a dozen ocean-liners, and he had cast them into space like a farmer sowing wheat upon the wind. (p. 102)

This was a great sci-fi story with gigantic spaceships and space travel. Exactly what I think of when I think of classic sci-fi. But then another sci-fi tale was much different from what I expected. “Day Million” was an exploration of sexual relations in the far, far future, where such relations evidently boil down to exchanging personally owned equations of a very complex nature. These equations, or formulas, are analogues of each individual’s self. When a person has someone else’s equation, this formula can evidently be recalled at will for future psychological pleasure — something like highly abstract internet porn! In the afterword Pohl claims his point in “Day Million” was that as bizarre as this sounds to us, our own sexual practices would be quite bizarre to ancient humans. Surely. But I bet ancient and modern sexual practices probably have more similarities than the bizarro sexual ideas that Pohl cooks up here. It’s no surprise when Pohl also relates that this story was published in Playboy magazine.

Another satirical piece Pohl gives is “The Midas Plague” set in a futuristic land of plenty but where everyone is burdened with consuming lots and lots of stuff. Rather than being pleasurable, the experience for people is actually quite burdensome, though stopping seems to be nigh impossible. Pohl writes:

Plenty is a habit-forming drug. You do not cut the dosage down. You kick it if you can; you stop the dose entirely. But the convulsions that follow may wreck the body once and for all. (p. 141)

Pohl clearly means the story as a satire against consumerism—another easy target. Though interesting, I didn’t quite see how the main character’s (Morey’s) solution really helped all that much at the end.

“Speed Trap” was an intriguing story about the life of jet-set, academic scientists who spend most of their time going around from conference to conference. Pohl’s main character in this story relates what he thought the world of cutting-edge science would be like when he was a grad student at MIT:

I thought I would be a lean, hungry-eyed scientist in shabby clothes. I thought probably I would never get out of the laboratory (I guess I thought spaceships were designed in laboratories) and I’d waste my health on long night hours over the slide rule. (p. 220)

But the life of the modern science turned out to be quite different. I can personally attest (though not a scientist, nor am I exactly “jet-set”) that the details and feel provided in “Speed Trap” are very close to some of what I’ve experienced or seen in the academic world of conferences. The main character continues:

You know, there really is no more stupid way of communicating information than flying 3000 miles to sit on a gilt chair in a hotel ballroom and listen to twenty-five people read papers at you. Twenty-three of the papers you don’t care about anyway, and the twenty-fourth you can’t understand because the speaker has a bad accent, and, anyway, he’s rushing it because he’s under time pressure to catch his plane to the next conference, and that one single twenty-fifth paper has cost you four days, including travel time, when you could have read it in your own office in fifteen minutes. And got more out of it too. (p. 221)

In an age when the internet allows papers to be sent around the world in a matter of seconds, this quotation is all too prescient. “Speed Trap” has an interesting twist of an ending that I didn’t see coming in that a worldwide conspiracy is evidently attempting to slow the progress of science. I think Pohl subtly suggests that this conspiracy is actually conducting the science conferences in order to slow the progress of science down. But, again, I don’t exactly remember the sci-fi elements here.

“The Day the Icicle Works Closed” is set in a space colony where a mining and manufacturing monopoly has gone belly-up. In the midst of this economic crisis, the story centers upon a defense attorney seeking to defend several young clients from a crime he truly believes they aren’t guilty of. Though set in a sci-fi setting, the whole story has a strong Law & Order feel to it. It’s a fairly gripping tale with mystery and good characterization but the sci-fi elements seemed superfluous here as well. Nevertheless, it’s a heck of a good Perry Mason-like story.

“How to Count on Your Fingers” was a little non-fiction piece about the benefits of binary numbers systems, such as those used in computers. This was a fun little informative piece, though perhaps a bit dated given that I think most people today understand that basic computer code works with only ones and zeros. This piece reminded me of a non-fiction science essay I read by Fritz Leiber once. Perhaps old school sci-fi writers used to do these sorts of Bill Nye science pieces on a regular basis. I don’t know. I do find it hard to imagine sci-fi authors today doing something like this (though maybe some do and I’m unaware of it). It would be great to see again science being popularized by sci-fi writers.

The last few stories in this volume turned out to be some of Pohl’s darkest. In fact, I would classify more than one of them as a horror story.

“The Hated” was a surprising, psychological, horror story, focusing particularly on the effects of long space travel on astronauts in small confined rockets. It has a sort of Inception or Matrix twist at the end but it still ended up being a fairly disturbing story. The sort of maniacal coldness the astronauts end up with is fairly chilling. Here’s a small taste:

She said triumphantly, “You want to find that other fellow from your crew! You want to fight him!” I couldn’t help shaking, white pills or no white pills. But I had to correct her. “No. I want to kill him.” (p. 289)

I didn’t quite see it coming but “The Martian in the Attic” had a horrific ending, thus turning it into something of a horror story as well. And the last story in this volume, “The Children of Night” is quite disturbing in describing child abuse and murder by alien beings.

Overall The Best of Frederik Pohl was a great collection of short stories, and quite varied. Some concluding thoughts though: I’ve commented more than once that the sci-fi elements in Pohl’s stories are sometimes hard to remember. Given Pohl’s prestige in the annals of science fiction, I was often surprised that these stories were not more strongly sci-fi, surprised that the sci-fi elements were not more to the fore in many of these stories. Perhaps I just have some misconceived notions of what “classic” science fiction should amount. Probably true.

I think it’s obvious that Pohl’s stories here are clearly science fiction. But if so, why did I perceive his sci-fi elements to be so tangential to his stories? I think it’s because of the following: Pohl is such a good story-teller that one tends to forget that you’re reading a science fiction tale. I think I was often so taken with the elements of the romance, or the procedure drama, or the intriguing characters, or the horrific elements that Pohl was giving that the sci-fi elements seemed to almost completely fall by the wayside. And maybe being a good meat-and-potatoes sci-fi writer just means being such a good writer your story seems just as at home in other genres than science fiction. At least that’s my take on Frederik Pohl.

I think Stanley Weinbaum was a genius in giving us some of the most “alien” aliens imaginable. And I still think Fritz Leiber was the sci-fi Shakespeare with his exquisite prose. But Frederick Pohl was neither of these. Yet, his story-telling abilities were solid and gripping. I highly recommend this volume.

Here’s the complete Table of Contents.

A Variety of Excellence by Lester del Rey

“The Tunnel Under the World” (1955)

“Punch” (1961)

“Three Portraits and a Prayer” (1962)

“Day Million” (1966)

“Happy Birthday, Dear Jesus” (1956)

“We Never Mention Aunt Nora” (1958)

“Father of the Stars” (1964)

“The Day the Martians Came” (1967)

“The Midas Plague” (1954)

“The Snowmen” (1959)

“How to Count on Your Fingers” (1956)

“Grandy Devil” (1955)

“Speed Trap” (1967)

“The Richest Man in Levittown” (1959)

“The Day the Icicle Works Closed” (1960)

“The Hated • (1958)

“The Martian in the Attic • (1960)

“The Census Takers” (1956)

“The Children of Night” (1964)

“What the Author Has to Say About All This” (1975)

Our previous coverage of the Classics of Science Fiction line includes (in order of publication):

Rich Playboys, Mad Scientists, and Venusian Monsters: The Best of Stanley Weinbaum

Vampires, Frozen Worlds, and Gambling With the Devil: The Best of Fritz Leiber

The Best of Henry Kuttner

The Best of John W. Campbell

The Best of C M Kornbluth

The Best of Philip K. Dick

The Best of Fredric Brown

The Best of Edmond Hamilton

The Best of Murray Leinster

The Best of Robert Bloch

The Best of Jack Williamson

The Best of Hal Clement

The Best of James Blish

See all of our recent Vintage Treasures here.

In some ways, I think of the SF by Fred Pohl in the same way I think of Orwell’s “1984” and Huxley’s “Brave New World”: no gadgetry, no alien tech, no time travel, no interplanetary intrigue, perhaps, but just enough SF to qualify as SF. One of Pohl’s better efforts with respect to SF content such as you’re missing here in his stories is his novel “Man Plus.” Although apparently not well-received by many SF critics, the story of a man being genetically altered to survive as a Martian is well worth the effort.

Thanks for the recommendation smitty59. I like your comparison of Pohl to Orwell and Huxley. That makes more sense of Pohl seeing him in light of those greats. Instead of saying Pohl is missing SF content, I should’ve said Pohl is subtle with his SF content.

Comparing Mr. Pohl to Orwell and Huxley is apt, as much of Mr. Pohl’s fiction (especially his collaborations with Cyril Kornbluth) are satires/commentaries on society, such as The Space Merchants or Gladiator-at-Law. For more “pure” sf, you may like their fix-up Search the Sky or Mr. Pohl’s Heechee series, starting with Gateway.

Thanks for the suggestions Eugene. Again, I think my “pure” sf thoughts on Pohl were more of some kind of skewed impression rather than a definite expectation. I was pleasantly surprised by Pohl’s stories.