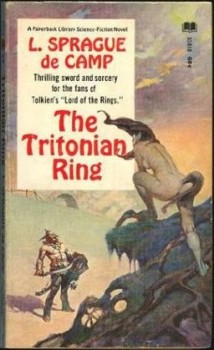

Logical Swords & Sorcery: The Tritonian Ring by L. Sprague de Camp

Lyon Sprague de Camp’s first published story was “The Isolinguals” in 1937. During the 1930s and 40s he became a significant author, writing dozens of stories and numerous novels. His time travel novel Lest Darkness Fall (1939) is considered a classic and is still read today. Alongside such genre standard bearers as Robert Heinlein and Isaac Asimov, he is considered one of the authors responsible for bringing greater sophistication to science fiction. He was the fourth Grand Master as chosen by the Science Fiction Writers of America in 1979, and in 1984 he was given the World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement. His 1996 autobiography, Time and Chance, won a Hugo Award. In his lifetime he was well-regarded and successful.

Lyon Sprague de Camp’s first published story was “The Isolinguals” in 1937. During the 1930s and 40s he became a significant author, writing dozens of stories and numerous novels. His time travel novel Lest Darkness Fall (1939) is considered a classic and is still read today. Alongside such genre standard bearers as Robert Heinlein and Isaac Asimov, he is considered one of the authors responsible for bringing greater sophistication to science fiction. He was the fourth Grand Master as chosen by the Science Fiction Writers of America in 1979, and in 1984 he was given the World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement. His 1996 autobiography, Time and Chance, won a Hugo Award. In his lifetime he was well-regarded and successful.

To call de Camp a polarizing figure is an understatement. His control over Robert E. Howard’s Conan character for so many years, his ham-fisted editing of Howard’s stories, his ruthless strangling of any effort to get pure, unadulterated Conan into print, raised the ire of readers. For an incredibly detailed history of de Camp’s relationship with REH’s work and legacy, I highly recommend tracking down Morgan Holmes’ 16-part series, “The de Camp Controversy.”

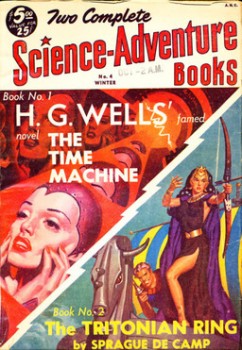

De Camp first encountered the character of Conan when his friend Fletcher Pratt tossed him a copy of Conan the Conqueror. According to Lin Carter, de Camp “yielded helplessly to Howard’s gusto and driving narrative energies.” In 1951 de Camp decided to try his own hand at Howardian swords & sorcery and wrote The Tritonian Ring. He sold it to the clunkily-titled magazine Two Complete Science-Adventure Books.

Set in the age before the sinking of the island Pusad (misremembered in our day as Atlantis), The Tritonian Ring is an attempt at a rollicking tale of adventure. When it is realized that the gods intend to destroy the kingdom of Lorsk, the prince Vakar is sent out on a mission to find the thing the deities most fear. In disguise, aided by only his personal slave and a less-than-trustworthy translator provided by his jealous brother, Vakar undertakes a quest that will send him across much of the known world and many of its unknown parts as well.

Set in the age before the sinking of the island Pusad (misremembered in our day as Atlantis), The Tritonian Ring is an attempt at a rollicking tale of adventure. When it is realized that the gods intend to destroy the kingdom of Lorsk, the prince Vakar is sent out on a mission to find the thing the deities most fear. In disguise, aided by only his personal slave and a less-than-trustworthy translator provided by his jealous brother, Vakar undertakes a quest that will send him across much of the known world and many of its unknown parts as well.

In a series of episodic chapters, Vakar meets a lusty queen, inquisitive scholars, scheming sorcerers, and conniving kings. A villainous priest of the pirate-nation Gorgon dogs his steps the entire way. Spies and conspirators belay him just when he thinks he’s safe. Of monsters, magic, and bloody swordplay there’s plenty. By all rights I should have loved this book now as much as I did when I first read it thirty years ago, but I didn’t. As The Tritonian Ring proves, chapter after chapter, de Camp was not temperamentally equipped for writing heroic fantasy.

As much as de Camp professed to love Howard’s writing, its historical inconsistencies irritated him. De Camp was a student of history and technology. In a 1963 essay in Amra magazine titled “Hyborian Technology,” he went piece by piece through the technologies of Hyboria, detailing how much of a mishmash they were. When he decided to write S&S, he hoped to avoid those sorts of errors and create a historically and scientifically consistent and accurate world.

This is the most enjoyable and artistically successful aspect of The Tritonian Ring. De Camp posits exactly what a magic-using Bronze Age antediluvian world would look like. Writing is still in its infancy and iron is unknown. Most kings and queens live at a level of comfort barely above that of their subjects. Instead of a jumble of Classical and Medieval trappings and technologies, Pusad and the various places in this book feel like that of Mycenae or the earliest city-states of the Fertile Crescent. There are no knights in shining armor, only spearmen in chariots. It’s a wonderful achievement that I was very much impressed with. In creating such a realistic world I expected a story similarly realistic, or at least sober-minded, but that’s not what de Camp delivered.

This is the most enjoyable and artistically successful aspect of The Tritonian Ring. De Camp posits exactly what a magic-using Bronze Age antediluvian world would look like. Writing is still in its infancy and iron is unknown. Most kings and queens live at a level of comfort barely above that of their subjects. Instead of a jumble of Classical and Medieval trappings and technologies, Pusad and the various places in this book feel like that of Mycenae or the earliest city-states of the Fertile Crescent. There are no knights in shining armor, only spearmen in chariots. It’s a wonderful achievement that I was very much impressed with. In creating such a realistic world I expected a story similarly realistic, or at least sober-minded, but that’s not what de Camp delivered.

In the introduction to de Camp’s Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy, Lin Carter wrote:

De Camp is too sane and civilized really to believe in heroes per se. He knows enough about history to realize that too often the heroes of this world, from Richard Francis Burton to Lawrence of Arabia, act in what seems to observers as a heroic manner because of inner weaknesses, compulsions, or desperate needs to overcompensate for what they dread is cowardice or less than complete masculinity. Knowing this, he finds it difficult to create fictional heroes who do not suffer from something which serves to goad them into acting like heroes — incurable gas pains, post-nasal drip, deviated septums, or a galloping mother fixation, let us say.

From the outset, de Camp seems constitutionally unable to believe in the sort of bold and fearless character of the same stripe as Conan. De Camp clearly feels a greater affinity for the clever man than the brave man, and though some effort was made to make Vakar heroic, it always rings hollow. Now, there’s room for clever, even cowardly, heroes in S&S, but Vakar comes across more as a ventriloquist’s dummy through which de Camp can voice his opinion on the natural gullibility, greediness, and cowardice of people.

Incidences of Vakar’s cleverness feel like the author reeling off some tidbits of historical information. We get to read in detail how a galley works and, in the middle of a horrible massacre, how to mount and guide a camel. De Camp seems incapable of silencing the pedant in himself and is always taking steam out of the action with one authorial lecture after another.

The worst part, the most irritating part of The Tritonian Ring, is the alleged comedy. From Lin Carter we learn that P. G. Wodehouse and Thorne Smith were among de Camp’s favorite authors. Particularly with Jeeves and Wooster, Wodehouse wrote some of the most critically acclaimed humor in the English language. Thorne Smith, best known for writing Topper, might feel dated today but, again, he was a skilled craftsman at writing funny.

For de Camp comedy rarely rises above cowardice and juvenile bawdiness. Vakar is always threatening his slave, Fual, with some dire punishment for the latter’s perpetual gutlessness. Instead of being genuinely fearful for his life, Fual is portrayed as a shirker making up implausible excuses for his absences during battles. Queen Porfia and the satyress are lusty and insatiable, which leads to several weak jokes.

For de Camp comedy rarely rises above cowardice and juvenile bawdiness. Vakar is always threatening his slave, Fual, with some dire punishment for the latter’s perpetual gutlessness. Instead of being genuinely fearful for his life, Fual is portrayed as a shirker making up implausible excuses for his absences during battles. Queen Porfia and the satyress are lusty and insatiable, which leads to several weak jokes.

There is a lame attempt at satire in the later chapters of The Tritonian Ring. After traveling through mostly realistic kingdoms and towns, Vakar suddenly finds himself negotiating a peace between the Tritons and the Amazons. Once a single tribe, they have split into male and female tribes over household politics. It is simplistic and not funny. Not in a “that’s not a subject for humor” way but in a “do you actually know any women? or real live people?” way.

Even worse is the land where foreigners are forbidden lest they upset the perfect order that has been achieved. Intruders into Gamphasantia are condemned to meet their fate in the arena. Gamphasants practice such absolute pacifism (they themselves don’t harm or kill, dumb beasts in the arena just do what they do) and consider themselves so advanced, they believe they will easily convince a tribe of raiders not to kill them. Not only is it not funny, it completely undermines the believability de Camp seemed to be striving for.

Finally, the book collapses as it rushes to a conclusion. The meddlesome gods vanish, Vakar retraces his footsteps far too rapidly, and an invasion of Lorsk, all occur in a only a chapter or two. It is very unsatisfying.

Finally, the book collapses as it rushes to a conclusion. The meddlesome gods vanish, Vakar retraces his footsteps far too rapidly, and an invasion of Lorsk, all occur in a only a chapter or two. It is very unsatisfying.

The Tritonian Ring is an interesting artifact from the early days of post-Howardian swords & sorcery. The worldbuilding is impeccable and interesting. I enjoy a book that draws on the real world’s Bronze Age civilizations for its inspiration instead of the same old generic European ones. De Camp’s extensive historical knowledge rings off every page, helping make Pusad one of the most detailed and believable fantasy worlds I’ve read. There’s a real vim and vigor to the early chapters, but de Camp’s lecturing and penchant for the not-funny always intrudes.

Unfortunately, the attempts at comedy trash it all. First and foremost, it’s just didn’t make me laugh, chortle, or even snort. Instead, my eyes rolled and I rushed to turn the page hoping things would improve, which they rarely did. Secondly, it doesn’t work with the detailed realism of Pusad. Perhaps if de Camp had striven for a deeper kind of comedy that really tried to expose the foibles and self-delusional nature of mankind, it could have. Instead there are unfunny jokes, glib cynicism, and tired characterization.

This is a book, one of the very few I’ve reviewed, of which I can unequivocally state: don’t read it.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Swords & Sorcery: A Blog when his muse hits him.

Hmmm … I have at least two copies, I think, but I’ve never quite gotten around to it. This certainly doesn’t move it any higher on my list.

“Logical” swords and sorcery?

Sounds very (un)exciting.

I read it. And I did quite enjoy it.

Not as much as the Harold Shea series, or Lest Darkness Falls, but… ok, sorry, I liked it.

I was sixteen and Sprague De Camp was one of the first authors I read in English – because his prose was clear and direct, and easy to get into. But I’m not offering this as an extenuating circumstance.

And to make my position worse, and my sins unforgiveable, I must say I very much like the idea of applying absolute, iron-bound logic to the fantasy genre.

After all, it’s from such a practice that the late Sir Terry Pratchett’s humor came from.

And granted, Pratchett was one thousand times funnier than Sprague De Camp. But the principle is the same, I think (and the same could be said for Christopher Moore’s novels, probably).

And now I’ll go sitting behind the blackboard.

I have a copy waiting to be read. Now I am in two minds as to whether I should bother. I like the idea of the world making sence in terms of technology.

@Joe H and Tony Den – I am probably too harsh in my final condemnation. It’s just the setting and the idea of a consistent and deliberately thought out setting are appealing, and his failure to write a story to match was a real disappointment. I just didn’t expect to dislike the book as much as I did.

@Davide M. – At twenty or so when I first read it I absolutely loved it. I have a stack of de Camp books that I loved twenty-five or thirty years ago. Unfortunately, when I reread Lest Darkness Fall, as brilliant as the idea of changing history with double-entry accounting is, there was a glibness to the book I found irritating. When I tried to reread The Fallible Fiend last year, a book I had very fond memories of, I couldn’t work past the second chapter. The comedy is strained and obvious, and didn’t make me laugh.

De Camp doesn’t even really take on the genre and its trappings as Pratchett did in the early Discworld novels, let alone use humor to explore the deeper elements of humanity as in the later ones.

@Tony D. and James M. – I would love to see someone create a logical, tech. consistent world, with an actual understanding of history, and then write a story equal to the setting. De Camp undercuts his world as well as some good writing and storytelling with lecturing and “comedy.”

I didn’t think it was “definitely don’t read it” bad, but I didn’t like it much, for the reason that a lot of DeCamp leaves me cold – the whole thing just didn’t seem to matter much to him.

I think that the cover blurb for the Paperback Library editions sums it up quite nicely: “Sword & sorcery for the fans of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings”. (OK, I did leave out the word “thrilling”, there.)

De Camp certainly did like explaining things, and did it well: his The Ancient Engineers (1963) is still in print. And Lest Darkness Fall makes the Justinian Re-Conquest of Italy seem like a disaster for the locals, which is the view of many current histories of the 6th Century CE.

My favorite de Camp book may actually be Great Cities of the Ancient World, followed closely by Lost Continents and Literary Swordsmen & Sorcerers.

@Thomas P. – I think that’s a better summation of the book’s problem than everything I wrote. If he was committed to the comedy or something, it might have been a better book. I’ve read he essentially dismissed S&S as light entertainment, but that doesn’t mean it needs to lack heart.

@Eugene R. – I’ve always meant to read Ancient Engineers. I might even have a copy of it somewhere.

@Joe H – I’ve got to see if I’ve got Lost Continents as well. It might be boxed up with my Velikovsky books.

@Joe H

I *love* Literary Swordsmen & Sorcerers!

LS&S is a great survey of some really important authors, mostly from the earlier days of the field.

And one of the things I really like about Great Cities is all of the Roy G. Krenkel illustrations.

Very good review. I didn’t like it when I read it years agon and I liked it even less when I returned to it just last year, it was worse then I remember. DeCamp took none of his Fantasy writings seriously, when should we.

@Joe K – It’s a real problem with much of his work. Despite good some good prose and clever ideas, too often, there’s no heart.

I tried the Tritonian Ring after reading the short story Eye of Tandyla in Isaac Asimov’s Wizards anthology. I suspect the short story was written first, as it more successfully executes the humor that falls so flat in the longer book. I honestly couldn’t finish the Ring, but I still wish he’d stuck to the short story format and given us more Derzong Taash and Zhamel Seh.

[…] Fletcher Vredenburgh on The Tritonian Ring at Black Gate. […]

[…] also invite you to read what Fletcher Vrendenburgh had to say at Black Gate. I think his feelings skew closer to my own, though I probably fall somewhere between him and […]