Vintage Treasures: Try a Little Sturgeon Caviar

|

|

|

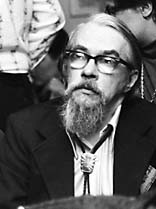

I started what eventually became a casual series of posts about Theodore Sturgeon back in June 2014, when I wrote a brief piece on his 1979 collection The Stars Are the Styx. It was casual because I’d make another entry in the series only when I acquired another of his collections. The result was eight posts over roughly two years, not a bad stretch, really.

The only real drawback to this system is I’ve been dying to do a post on his 1955 collection Caviar, perhaps my favorite of his many books, and a copy has not tumbled into my hands for many years. So I’m breaking with my system (and had to troop upstairs and root around on the shelves until I found a copy, no small accomplishment) to bring you this report. You’re welcome.

Why is Caviar my favorite? Nostalgic reasons, mostly. It contains “Microcosmic God,” the first Theodore Sturgeon tale I can remember reading, and still one of my favorites.

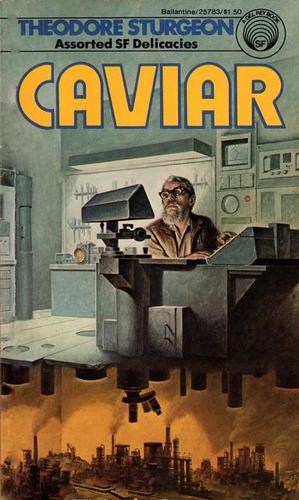

Also, I had a lot of fun tracking down the various paperback versions, especially the 1977 Del Rey edition with the brilliant cover by Darrell K. Sweet (above right), which pretty clearly has publisher Lester del Rey putting in a cameo appearance as “Microcosmic God”‘s genius inventor James Kidder.

“Microcosmic God” was first published during World War II, in the April 1941 issue of Astounding Science Fiction. Sturgeon was a Campbell discovery; although he started selling short stories to the McClure Syndicate for newspaper syndication in 1938, his first SF sales was “Ether Breather,” which appeared in the September 1939 issue of Astounding. Sturgeon sold Campbell a steady stream of stories for many years, for both Astounding and its sister magazine, Unknown.

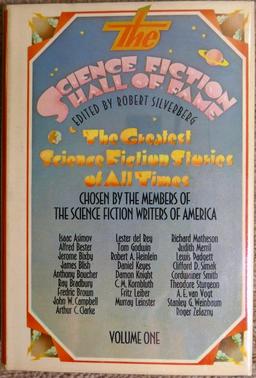

“Microcosmic God” became an acknowledged classic. When the Science Fiction Writers of America asked its membership to select the top SF stories prior to 1965 (when the Nebula Awards began), it came in fourth on the list. I first read it in Volume One of The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, which gathered all the winning entries in that poll.

“Microcosmic God” became an acknowledged classic. When the Science Fiction Writers of America asked its membership to select the top SF stories prior to 1965 (when the Nebula Awards began), it came in fourth on the list. I first read it in Volume One of The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, which gathered all the winning entries in that poll.

The story is perhaps the perfect distillation of Campbellian science fiction. A lone inventor, scornful of wealth and fame, becomes so successful and rich that he buys an island of the coast of New England. There he finds a way to both create life, and accelerate evolution. He creates a massive underground laboratory where he guides a tiny species up the evolutionary ladder, constantly testing them and rewarding their ingenuity, until they are both highly advanced and regard him as an absolute deity. He then harvests their many inventions, becoming the greatest inventor in history.

His scheme starts to unravel, as it usually does in these stories, with the arrival of a villain — in this case a greedy banker — who has a low opinion of science, and sees it purely as a way to make a profit. The world-changing ending, and the chilling final line, drove home the point that all Astounding readers thrilled to: those who scorn science do so at their peril.

While “Microcosmic God” still packs a wallop, it hasn’t aged particularly well. Fortunately that’s not true of many of the other stories in Caviar — particularly “Shadow, Shadow, on the Wall” (from Imagination), with features Sturgeon at his most Stephen King-like. A young boy with a vivid imagination finds himself the victim of a cruel stepmother, intent on punishing him for breaking a window. We see everything in the story through young Bobby’s eyes — including his stepmother.

She clicked the high-up switch, the one he couldn’t reach, and room light came cruelly. Mommy Gwen changed from a flat, black, light-rimmed set of cardboard triangles to a night-lit, daytime sort of Mommy Gwen.

Her hair was wide and her chin was narrow. Her shoulders were wide and her waist was narrow. Her hips were wide and her skirt was narrow, and under it all were her two hard silky sticks of legs. Her arms hung down from the wide tips of her shoulders, straight and elbowless when she walked. She never moved her arms when she walked. She never moved them at all unless she wanted to do something with them.

“You’re awake.” Her voice was hard, wide, flat, pointy too.

Gwen takes away all of Bobby’s toys and locks him in his room, forcing him to prop up a lamp and make a shadow theater to amuse himself. When Gwen hears him laughing and storms into the room, intent on taking away whatever toys he’s hidden away, she discovers that not all the shadows on the wall are of Bobby’s making.

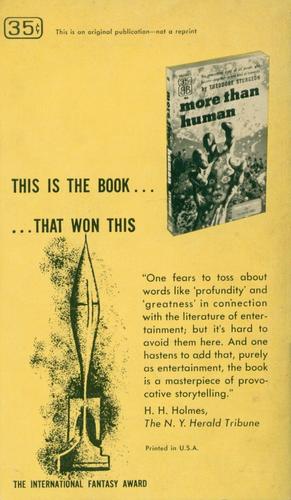

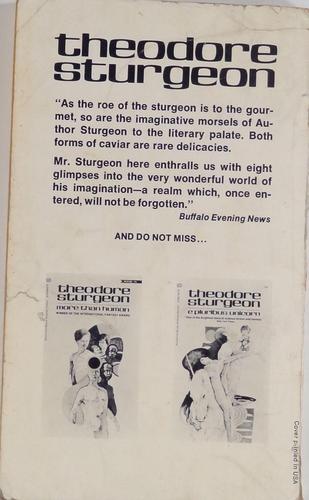

At the height of Sturgeon’s popularity in the 1950s, he was reportedly the most anthologized English-language author alive. When Caviar first appeared as a Ballantine original in 1955, he’d just won the International Fantasy Award for his novel More Than Human, and the back of the paperback proudly trumpeted that accomplishment (bellow left). Here’s the back covers for all three of the paperback editions shown above.

|

|

|

[Click any of the images for bigger versions.]

Caviar was reprinted ten times over the next twenty years. Here’s the publishing details for all three editions shown above:

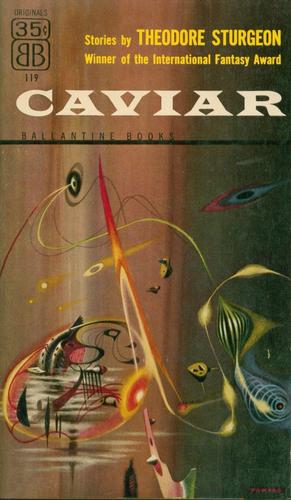

Ballantine Books (168 pages, 35 cents, November 1955) — cover by Richard Powers

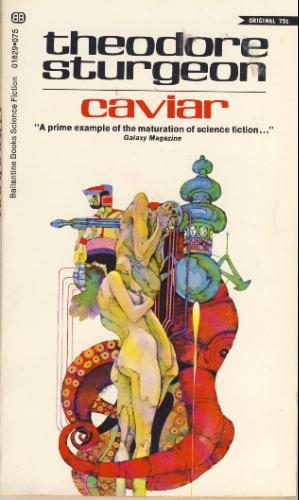

Ballantine Books (168 pages, 75 cents, January 1970) — cover by Robert Pepper

Del Rey/Ballantine (182 pages, $1.50, April 1977) — cover by Darrell K. Sweet

There’s lots of interesting things about these editions. For example, the 1970 paperback edition offered this fine quote on the cover:

There’s lots of interesting things about these editions. For example, the 1970 paperback edition offered this fine quote on the cover:

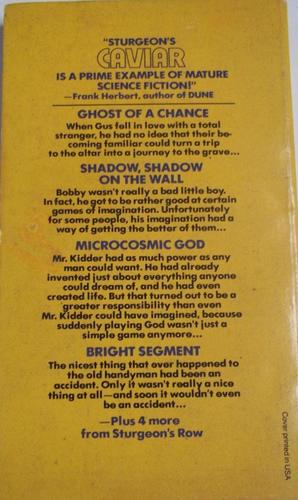

“A prime example of the maturation of science fiction…” Galaxy Magazine

By the time the 1977 edition rolled around however, that humble Galaxy reviewer had become more famous than the magazine he was published in. The (now corrected) proudly appeared on the back of the Del Rey edition with a very different attribution:

“Sturgeon’s Caviar is a prime example of mature science fiction!” — Frank Herbert, author of Dune

Here’s the compete Table of Contents:

“Bright Segment” (original to this volume)

“Microcosmic God” (Astounding Science-Fiction, April 1941)

“Ghost of a Chance” (Unknown Worlds, June 1943)

“Prodigy” (Astounding Science Fiction, April 1949)

“Medusa” (Astounding Science-Fiction, February 1942)

“Blabbermouth” (Amazing Stories, February 1947)

“Shadow, Shadow on the Wall” ( Imagination, February 1951)

“Twink” (Galaxy Science Fiction, August 1955)

Most of the stories in Caviar appeared before the major SF awards were established. However, Twink did receive a 1956 Hugo nomination for Best Short Story.

Our previous coverage of Theodore Sturgeon includes:

The Joyous Invasions (1965)

A Touch of Strange (1958)

Not Without Sorcery (1961)

Sturgeon in Orbit (1964)

Starshine (1966)

Sturgeon is Alive and Well… (1971)

To Here and the Easel (1973)

The Stars Are the Styx (1979)

Caviar proved elusive for me, but that’s chiefly because I buy in bulk these days. When I checked this afternoon, there were 17 copies available on eBay, ranging in price from $3 – $12 for a paperback edition.

Caviar was published as a paperback original in November 1955 by Ballantine Books. It is 168 pages, priced at 35 cents. The cover is by Richard Powers. It has been out of print for 29 years, and there is no digital edition.

See all of our recent Vintage Treasures here.

As an old retired English teacher, I have to point out that “Microcosmic God” is the title of the story. That autocorrect can be a real pain sometimes.

Bill,

I could blame autocorrect, but truthfully I should have caught it at least ONE of the five times it popped up in the text.

Ah well. Thanks for the correction. At least one of us is paying attention. 🙂

Thanks for this! I really enjoy these posts on vintage paperbacks–and on Sturgeon, particularly. I have and use the monumental series of “Complete Stories of TS” from North Atlantic books, but somehow I always enjoy the stories more when I read them in one of Sturgeon’s own non-complete collections.