What We Can Learn From a Time Lord: Doctor Who and a New Enlightened Perspective

There’s an underrated benefit to science fiction and fantasy, and it is not dissimilar from a benefit one gains by being a student of history. Since many folks consider speculative fiction and historical scholarship (or “flights of fancy” and “recorded fact”) to be the antithesis of each other, I think this benefit is worth some attention.

There’s an underrated benefit to science fiction and fantasy, and it is not dissimilar from a benefit one gains by being a student of history. Since many folks consider speculative fiction and historical scholarship (or “flights of fancy” and “recorded fact”) to be the antithesis of each other, I think this benefit is worth some attention.

The benefit I here have in mind is the gaining of a healthy detached perspective. Detractors of fantasy and sci-fi will immediately object to my use of the word “healthy,” being that they regard such literature as mere escapism. And it often is that, yes. As is golf, and the Super Bowl, and birthday parties, and most fun things that we do when we aren’t engaged in utilitarian labor. But I’m thinking about a different sort of escape: escape from our own temporal status in this particular time and place and culture and society to which we were born. This is a benefit that is greatly under-appreciated, but I believe it holds real power.

The reader of science fiction, like the historian, steps out of his or her own time frame: if you’re a historian, you step back in time; if you’re a sci-fi fan, you become accustomed to stepping ahead into some speculative future. And if we cultivate that mental exercise, it gives us the unique opportunity to look at our own time from that same detached perspective.

When you do this, it can be liberating. We put so much stock in what people say. We are angered, hurt, offended, cut to the core by what we are bombarded with when we turn on the TV or log onto Twitter or get together with family over Thanksgiving dinner. But the power of these viewpoints — and the hostile ways in which they are sometimes expressed — to affect us is really only predicated on the fact that we are alive now and that these are opinions being expressed by our contemporaries.

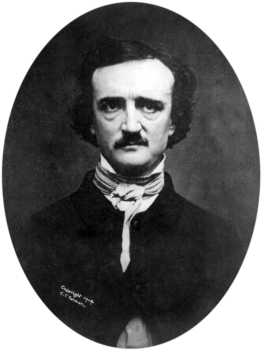

Edgar Allan Poe cared deeply about what Rufus Wilmot Griswold thought. Poe would read the latest invective his literary adversary had published to defame him, go into a rage and turn to the bottle. Now, two centuries on, most of us say, “Who the hell was Rufus Griswold?” We could care less what Griswold thought, except with a historical interest insofar as it relates to the biography of Poe. Some people’s opinions do matter more than others; it’s just harder to make that distinction when you are standing in the same room or reading the same newspaper.

Edgar Allan Poe cared deeply about what Rufus Wilmot Griswold thought. Poe would read the latest invective his literary adversary had published to defame him, go into a rage and turn to the bottle. Now, two centuries on, most of us say, “Who the hell was Rufus Griswold?” We could care less what Griswold thought, except with a historical interest insofar as it relates to the biography of Poe. Some people’s opinions do matter more than others; it’s just harder to make that distinction when you are standing in the same room or reading the same newspaper.

If we can detach ourselves for a moment from the place and time we happened to be born — rise above the timeline…

Imagine, for a moment, a person living in your town a hundred years ago (assuming the place where you live is at least a hundred years old). A hundred years ago this person would have been your neighbor. For the sake of this thought experiment, let’s say he is just a typical citizen — not someone who would have made it into any history books or had any especial impact on the future. Just a person who came, lived his life, and went. It has been said that most of us will have been completely forgotten within three generations. Oh, our name might appear on a family tree assembled by a great-great grandchild who has a mild interest in genealogy, but that’s about it. Heck, most of the most important scientists, politicians, and writers of one generation are all-but-forgotten within three generations, so don’t feel left out.

But back to the thought experiment: This now-forgotten person, let’s say he was a racist. He vocally expressed his opinion that minority races were inferior (and without much backlash, what with this being a hundred years ago). He was a respected, well-regarded member of the community. What do you care about what he thought? Put another way, how much does his opinion influence your own?

Considering this man’s opinion, you are likely troubled and upset — you may even feel a little anger well up in you at the injustices of the past — when you think about this kind of nasty bigotry and the impact overt racism had throughout the ignominious periods of slavery and Jim Crow, and the lingering aftershocks of more subtle and covert racism that still ripple through our society today.

But really, you couldn’t give a flying Fig Newton about that hypothetical individual’s opinion. It means nothing to you. Why should it? When you consider issues of race, you don’t consult what this guy who lived in your town a hundred years ago might have had to say about it. You dismiss his views as being mostly a product of his time and culture and his own ignorance and lack of imagination.

This thought experiment is not intended to suggest that history is not important; to the contrary, what an “everyday” individual thought and said and did can be incredibly illuminating to a historian. However, the relevance of that individual’s opinion to your own is virtually nil. It’s sad to think that his racist views may have influenced his own children and his neighbors. But they’re all dead too.

If tomorrow you stepped inside a time machine and found yourself standing in the yard of this man who is separated from being your neighbor only by the passage of a century, then suddenly his opinions would become somewhat more relevant because now you would actually have to interact with him. But they would not become any more credible to you just because you were now hearing them face-to-face. You would still hear them from the vantage of having come from the future.

If tomorrow you stepped inside a time machine and found yourself standing in the yard of this man who is separated from being your neighbor only by the passage of a century, then suddenly his opinions would become somewhat more relevant because now you would actually have to interact with him. But they would not become any more credible to you just because you were now hearing them face-to-face. You would still hear them from the vantage of having come from the future.

Now imagine your life today not as if you were living in your own time but as if you were visiting from a hundred years in the future. The weight given by proximity, i.e., these people are my neighbors, is leveled off, much the way that visiting that long-dead neighbor would be. Detach yourself from all the noise of the television and the Internet and your workplace, your college, your local pub. See it from a more objective position — of not being of this time, with the knowledge that this time, too, will pass, and all these people who are speaking right now; they all, too, will be dead and most of them forgotten.

They will be remembered not as individuals, for the most part, but in the aggregate, just as we remember peoples of the past (necessarily so — there are too many people to remember any but a few representatives): Tories and Revolutionaries; The pro-slavery lobby and the abolitionists; the supporters of women’s suffrage and the sexists, etc. A hundred years from now you will be similarly aggregated: LGBT allies and those who opposed gay marriage; those who believed climate change was happening and climate-change deniers, and so forth.

These views, and the rhetorical (and sometimes real) battles fought over them, will matter with regard to how they shape the future, but your own personal opinion will not weigh in much. Nor, however, will that of your neighbor or the person on Facebook who really got you riled up today. You will all have been swept off the stage, making way for new actors strutting back and forth playing out their own acts, intensely debating and fighting over their own issues, barely recalling that you and your contemporaries ever performed here debating your own issues that were so important once upon a time.

These views, and the rhetorical (and sometimes real) battles fought over them, will matter with regard to how they shape the future, but your own personal opinion will not weigh in much. Nor, however, will that of your neighbor or the person on Facebook who really got you riled up today. You will all have been swept off the stage, making way for new actors strutting back and forth playing out their own acts, intensely debating and fighting over their own issues, barely recalling that you and your contemporaries ever performed here debating your own issues that were so important once upon a time.

This is not my cynical ploy to demonstrate that none of it matters or that our views and opinions don’t count (in the aggregate, at least, they will shape the future, laying the course for our progeny); nor is it my intent to suggest that we should not hold strong views. History will preserve these struggles of our day in broad, generalizing strokes; whatever the legacy of our time, we are part of this time and so it is also our legacy. That should matter to us (tempered by the humbling recognition that we are but one person among billions).

Again, I spoke of a benefit. What is liberating about this more detached, long-term view is the objectivity it imparts to us. A post that showed up on your Facebook wall today that got you emotionally bent out of shape and a sentiment written in a letter sent a hundred years ago: the only reason that the former affects you so much while the latter would not (except to pique your curiosity about what was written in this hundred-year-old artifact) is simply because the Facebook post happened today, and you happen to be living today, not a hundred years ago.

If you can unhook yourself — at best temporarily and imperfectly — from today, step back, and see that Facebook post from the same altitude and attitude that you see that yellowing letter, it really tamps everything down and puts it into a more realistic perspective. You can listen to what your conservative and liberal friends are gnashing and gnawing about with a curiosity less clouded by subjective, emotional involvement. Your frame of reference becomes wider than all that.

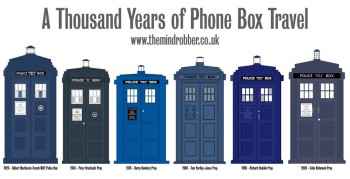

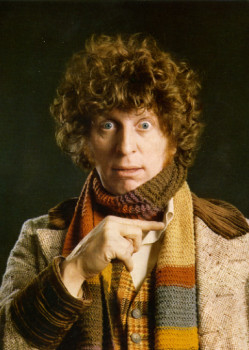

What’s so fun about a show like Doctor Who — aside from the crazy aliens, the scary robots, and the really cool Time And Relative Dimensions In Space craft — is how the doctor visits different eras and, along with his curiosity and his (sometimes) compassion, brings a playful perspective recognizing the biases and blind spots of the culture he is visiting. Their ignorance and narrow perspectives are, to a Time Lord, at best cultural oddities. When an aristocrat of ancient Pompeii insults the Doctor, the old saying could never be more true that “sticks and stones may break my bones, but words can never hurt me.” Of course he can’t help but find it amusing, hearing such a verbal attack from the context of his superior perspective.

Most effective is when he visits our own time, bringing with him to this world we take for granted that same disarming attitude. He reacts the same way to blowhards and narrow-minded individuals of the twenty-first century as he does to their analogues in the sixteenth. Because, to him, they’re all in the past.

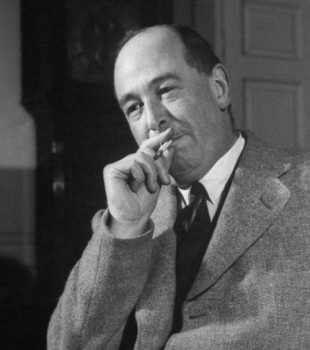

But there’s a corollary advantage for the good Doctor (and, by association, the companions who travel with him): He isn’t swayed by “chronological snobbery,” as C.S. Lewis and Owen Barfield dubbed it. That is, while the Doctor does not assign any special weight to the views and opinions of any one time, he also does not discount the thoughts or insights or creative endeavors of any person simply because he or she lived a few hundred (or a few thousand) years earlier. He recognizes genius, the best in humanity regardless of the clock.

We, on the other hand, are sometimes too quick to dismiss what someone said because he or she said it two thousand or two hundred or two years ago. If we disentangle ourselves from chronological bias, though, we recognize that much of what Plato or Aristotle said 23 centuries ago is better than most of what is being said in the wash of verbal spew we are swamped with today. Their views are still relevant, not rendered obsolete simply because they died a long time ago.

Taking in the view from this long perspective, then, we come to recognize that most of the noise made by the modern human race in its 200,000-year history (6,000 for civilization as we define it) is just that: a cacophony of mostly parroted and ill-considered, unexamined noise. But from that noise there arise notes of genius, and they are scattered throughout the ages: Socrates, Shakespeare, Van Gogh, Emily Dickinson, Duke Ellington, Miyazaki. I intentionally picked six names that you will likely never again see listed together — but they are illustrative; they are just six among the hundreds or thousands who represent heights of human thought and creative expression.

If you wanted to expand the representation to other human endeavors like science or politics, you could add Galileo and Lincoln — again, it is just an arbitrary selection of a representative few, but there are hundreds of other examples you could include: the point is that no one era corners the market on genius. A further point is that while there are thousands of great thinkers and artists, they are always working within the madding crowd of noisemakers. Stepping away to a more detached view makes it easier to hear those purer notes rising from the bedlam.

We cannot, alas, all be Time Lords. But we can learn from one. The more we become a companion to our Higher Self, the better our vantage in knowing and appreciating what really matters. A more objective, detached — “alien” if you will — perspective provides new angles, and the important stuff stands out in sharper relief from all the background noise. And unlike sticks and stones, all that distracting noise will be less likely to hurt us.