The Wasteland: Swan Song by Robert McCammon

|

|

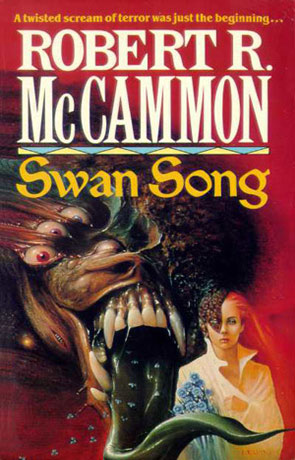

Swan Song

By Robert McCammon

Pocket Books (956 pages, $4.95, June 1987)

Cover by Rowena Morrill

Post-apocalypse tales are a rising star these days. Mad Max: Fury Road is rightfully acknowledged as a high-water mark for action films. Most recently the release of Bethseda’s Fallout 4 has anyone who calls himself a gamer holed up for power-armored adventure in the American wasteland. Whether the apocalypses are caused by nuclear blasts, hordes of the undead, or simply climate change, they consistently capture the imagination of millions.

The appeal is easy to understand. Our imaginations suggest that the collapse of civilization would give us ordinary people a chance to be heroes, to transform our baseball bats into swords, to see our commuter vehicles transformed into heroes’ chariots. We spend idle time in fluorescent-lit cubicles wondering how we’d fare if a mushroom cloud rose over the horizon.

Most post-apocalyptic settings have a clear surface pessimism. The end of civilization isn’t generally something to smile at. But I think the genre’s enduring popularity can be found in an underlying optimism about the ability of (relatively) ordinary people to become heroes in the most extreme circumstances imaginable. The misery of radioactive mutations or mass deaths are the grim background which makes the courage and heroism of the survivors all the brighter.

The fact that this heroism is set in a twisted version of our world helps the escapism. Five years from now, given the right cataclysm, any one of us could be a road warrior, cruising the wasteland in a Pursuit Special, or a knight of the Brotherhood of Steel, or a kind-hearted hermit offering hope to the hopeless in the wilderness.

The fact that this heroism is set in a twisted version of our world helps the escapism. Five years from now, given the right cataclysm, any one of us could be a road warrior, cruising the wasteland in a Pursuit Special, or a knight of the Brotherhood of Steel, or a kind-hearted hermit offering hope to the hopeless in the wilderness.

This is why I was initially surprised to see Robert McCammon’s Swan Song labelled as horror, rather than science fiction. Post-apocalyptic tales rely on their darkness for their power. Lord Humungus isn’t a nice guy. Cannibalism, slaughter, and disease are common elements in these stories. But I still wouldn’t categorize most of the ones I’ve seen, even many of those with zombies, as real horror.

But Swan Song earns its horror label. Earns it so well, in fact, that I suspect it will color my impressions of the entire genre.

It’s a fat brick of the novel, nearly a thousand pages in the paperback edition I read, and uses that length to dig deep into misery. Nuclear war, for example: most stories start with the war years in the past. The war in Swan Song happens on about pg. 100. McCammon shows the sheer scale of the destruction and slaughter and the way that even the survivors don’t come out unscathed, mentally or physically. This is a book full of infected wounds, oozing burns, coughed-up blood, and a particular disease that slowly covers the heads of the afflicted with rock-hard growths.

None of our heroes is exactly in a good place when we meet them. Susan Wanda (shortened to Swan) is a nine year-old girl with a particular talent for plants who follows her mother from one dilapidated trailer and one abusive man to the next. Josh is a traveling wrestler known as the “Black Frankenstein”, slowly losing his massive strength to back and joint complaints. His ex-wife has a new husband, and his two daughters live exclusively with her. Sister Creep doesn’t remember her name, or much of anything before her life as a homeless woman on the streets of a particularly dark version of New York City. Then there’s Roland, who… isn’t quite a hero. He’s a twelve year-old boy who starts off doing pretty well, joining his parents in an exclusive fallout shelter built under a mountain. But McCammon’s vision of the future is much too bleak for fallout shelters to be anything but rat-holes of starvation and infighting.

The book was first published in 1987, and the so the apocalypse is pretty standard: after escalating global tensions, the Soviet Union and the United States unleash the full fury of their nuclear stockpiles on each other, effectively annihilating every population center in the United States.

Josh the wrestler ends up buried beneath the same Nebraska gas station as Swan, in an improvised basement shelter. They initially live in darkness, nursing agonizing burns and surviving off canned goods buried with them, while the gas station owner and Swan’s mother die slow, horrible deaths from burns. Josh does what he can to keep Swan alive and intact, and a friendship builds between them, particularly when the corpse of the station owner resurrects for long enough to command Josh to “Protect the child.” When they finally dig their way out, the world they knew is absolutely gone. Dust storms sweep across a new Great Plains scoured of all life.

Sister Creep stays alive by hiding in the New York sewers, but still emerges horribly injured, covered in burns. She meets up with a handful of other lost souls in the ruins of New York, including a shoe salesman trying to get back to Detroit to find his wife. She also discovers a strange artifact made from fused glass and gems in a razed jewelry store: a glass ring with spikes melted on to make it a crown. The ring seems to glow with inner light when she holds it, and strikes her as a miraculous beauty in a world turned completely ugly.

Sister Creep stays alive by hiding in the New York sewers, but still emerges horribly injured, covered in burns. She meets up with a handful of other lost souls in the ruins of New York, including a shoe salesman trying to get back to Detroit to find his wife. She also discovers a strange artifact made from fused glass and gems in a razed jewelry store: a glass ring with spikes melted on to make it a crown. The ring seems to glow with inner light when she holds it, and strikes her as a miraculous beauty in a world turned completely ugly.

But Sister and her friends are also pursued by a figure of absolute evil. The book eventually calls him the Man with the Scarlet Eye, and he’s established as a shape-shifter — a literal man of a thousand faces. Sister and her companions manage to evade him once, but they know he’s pursuing them as they flee into the wolf-haunted wilderness of upstate New York.

Swan Song follows three different plot-lines in alternating chapters, which don’t insect until about the last 200 pages of the book. The main plot is Josh and Swan struggling to eke out survival in the wasteland that has replaced America’s breadbasket, while Sister—guided by prophetic visions—tries to find and meet up with them for reasons she doesn’t fully understand. Young Roland and his mentor, former Army Ranger and mercenary Colonel Macklin, take a somewhat different path, eventually rising into the roles of marauding warlords, fighting other mechanized bands of survivors over dwindling supplies of food, water, gasoline, and car parts.

Those marauders are about what you’d expect if you’ve seen ROAD WARRIOR (which was probably an influence, coming out six years before SWAN SONG), but McCammon uses the sweeping sprawl of his novel to do something movies normally can’t: dig deep into the sheer misery, not only of the marauders’ victims, but of the marauders themselves. It’s here that SWAN SONG packs quite a bit of its horror. The descent of Roland from relatively normal preteen to depraved madman is particularly unsettling. The wasteland brings despair even to those who establish themselves as predators. Perhaps especially to them.

The bleakness of Swan Song is central to what, in old-fashioned terms, I would call the novel’s argument. While the horrors of apocalypse turn many people into monsters, they make others into heroes. Josh, in particular, goes from being a kind-hearted failure to being something more like a knight-errant, the sole defender of an untouched innocent in a hellish world. And Swan is the embodiment of purity and good-heartedness. Her last words to an abusive live-in boyfriend of her mother’s are “I forgive you”, and that attitude defines her character. Those exact words recur at a critical moment later in the novel.

Swan’s goodness is, in fact, supernatural. As a child, she possesses an extraordinary green thumb, able to cultivate flowers and shrubs in nearly any patch of dry soil. As she grows, she becomes the only person who can seem to keep anything alive in the irradiated wasteland, to an extent that is eventually revealed as miraculous. Swan serves more than just an innocent role — she’s a kind of Madonna, a holy woman who can bring hope to a truly hopeless world. Her goodness, in turn, remakes Josh into a champion, bearing a prophetic obligation to “Protect the child”.

A figure of pure goodness requires one of pure evil. The Man with the Scarlet Eye is, depending on how you read the novel, either something like Cain, or else Satan himself. His purpose is explicitly the annihilation of hope, and with it the snuffing out of humanity. Once he learns about any source of hope — whether Swan herself, or Sister’s glass ring — it becomes his hell-bent mission to find it and destroy it. The Man is an embodiment of everything evil, selfish, and despairing.

If that makes Swan Song’s moral sense sound pretty black-and-white… that’s because it is. The “argument” McCammon makes is that apocalypse pushes everyone to extremes. Either men and women rise above their circumstances and become heroes, or else they become villains. These categories aren’t fixed — characters cross from one side to the other on multiple occasions, and hopeless people find reasons to keep living — but McCammon is explicitly writing in a world of moral absolutes.

If that makes Swan Song’s moral sense sound pretty black-and-white… that’s because it is. The “argument” McCammon makes is that apocalypse pushes everyone to extremes. Either men and women rise above their circumstances and become heroes, or else they become villains. These categories aren’t fixed — characters cross from one side to the other on multiple occasions, and hopeless people find reasons to keep living — but McCammon is explicitly writing in a world of moral absolutes.

I personally don’t think that weakens the book. In fact, I found it to be a strong point of story-telling vision, and the element which justified the book’s crushing bleakness. When you’ve spent 600 pages being beat down by the horrors of existence, the ultimate shifts towards hope and redemption feel like a cool drink of water after hours in a kiln.

All this builds to a climax when, seven years after the war, the survival of those who remain is once again weighed in the balance. Is humanity ultimately corrupt, and deserving of extinction, or can we rise above our evil nature? The way Swan Song resolves the question relies on explicit supernatural elements, pushing the book from science fiction to fantasy, but is ultimately satisfying. The journey may be agonizing, but the destination is worth it.

I don’t mean to imply that Swan Song is a staid Pilgrim’s Progress, either. There’s plenty of action, including a thrilling sequence set in a K-mart taken over by escaped psychopaths who have their own ideas of a “Blue Light Special”, as well as tangles with mutated wildcats and motorized platoons of wasteland stormtroopers. The book largely earns its length, as well. It never stays in one place long enough to get boring.

Reading the book has actually affected my real life feelings about preppers, shelter builders, and the like. I agree that it’s absolutely useful to have emergency supplies on hand for common situations like snow storms, and even for more severe disasters like hurricanes and earthquakes. But if civilization truly collapses, I’m doubtful that a stockpile or batteries and MREs will really be what separates the survivors and the victims. Survival in such an event will be more predicated on the ability and willingness of people to cooperate than on who has the most stuff.

Swan Song is a book I greatly enjoyed, and it carved out its own place in my imaginative landscape. It is, however, a brutal experience, and so I can only give it a qualified recommendation.

Sean’s last review for us was Gaunt’s Ghosts: Sabbat Martyr. He is currently living and working as an English teacher in Lviv, Ukraine. He keeps a blog at flinteye.wordpress.com, where he blogs about life in Ukraine, the art of teaching, and whatever stray thoughts flutter through the echoing chambers of his mind.

Nice review. The book seems like it’s still readily available. I might have to check it out.

“Survival in such an event will be more predicated on the ability and willingness of people to cooperate than on who has the most stuff.”

I really have to agree with you here. The ‘bug out’ crowd seems kind of silly to me. If civilization ended the first thing I would do is go tribal and start gathering up as many people I knew that I could. Human beings didn’t make it this far as solitary predators

This book is often compared to The Stand (apocalyptic novels with heavy Christian imagery and themes), but the nature of the apocalypse in each book considerably changes them in that a nuclear war is obviously going to do very different things to people than a super-flu would. I also think Swan Song is a better book in that it has better pacing and I think McCammon’s characters are more believable than King’s. McCammon’s book also features a pro wrestler as the hero, which immediately gives it a boost in my eyes.

Great to see Robert R. McCammon get more coverage here at Black Gate!