British Museum Presents Egypt: Faith After The Pharaohs

Ancient Egypt is famous for its elaborate religion with a multitude of deities and an obsession with the afterlife. While there have been many exhibitions on ancient Egyptian religion, it’s rare to see one that traces Egypt’s transformation from a land that was mostly pagan to one that was mostly Christian, then mostly Muslim, with a strong tradition of Judaism running through it.

Now a major exhibition at the British Museum, Egypt: Faith after the Pharaohs, uses about 200 objects to explore the history of religion in this fascinating country. The first gallery emphasizes that Egypt still has a sizeable Christian community. While that community has been targeted by extremists in recent years, there is also a large amount of cooperation between the two faiths. Photos from the Arab Spring show Christians making a protective ring around Muslims as they pray, and the Muslims returning the favor around churches on Sunday. The Western media tend to skip these stories of tolerance for more ratings-friendly tales of bloodshed, thus giving a skewed picture of the situation. As one of my old newspaper editors said, “If it bleeds, it leads.”

The exhibition then looks at the variety of religious traditions in the early centuries AD. One item is a letter from the Emperor Claudius (reigned 41-54 AD) concerning the cult of the divine emperor and the status of Jews in Alexandria. As paganism’s hold on the people began to wane, several emperors tried to strengthen it by forcing people to sacrifice to the emperor. If you didn’t sacrifice, you faced legal penalties. If you did sacrifice, you got in trouble with your religious community. A letter dating to 298 AD by a Christian to his wife tells how he got around this by getting someone else to make the sacrifice in his place.

Egypt, especially Alexandria and the desert monasteries, was a hot spot of early Christian activism. Once the religion was well established, the country became a center for Christian learning and pilgrimage. One telling group of objects is several pilgrim’s flasks from the shrine of St. Menas near Alexandria. Such flasks, which were an early precursor to the tourist souvenir, have been found from Britain to Uzbekistan.

By far the most important artifact in this section is the 4th century AD Codex Sinaiticus, the earliest complete copy of the New Testament. One of the strangest artifacts is a 10th century AD curse that calls on Apollo, who the Christian author considered a demon, to cause a divorce.

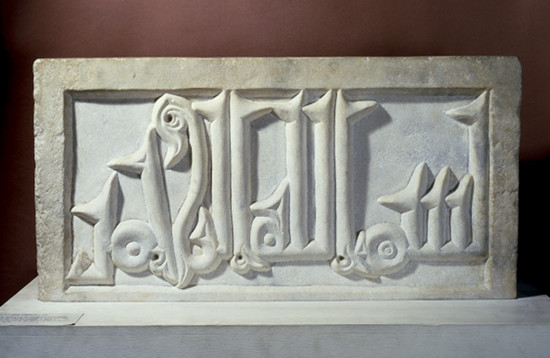

In Egypt, religions merged and lived on top of one another. At Alexandria, the Caesareum started by Cleopatra VII and completed by Augustus later became the Great Church of Alexandria. The al-‘Attrin Mosque in Alexandria used hundreds of old Roman columns. In Cairo, several synagogues were built in an old Roman fort. The famous temple of Hatsheput had a Christian monastery built atop it in the the 7th century that lasted until only about 60 years ago. The exhibition has an 11th century Hebrew Bible written in Arabic script. There’s also a gem with Anubis carved on one side and the Archangel Gabriel on the other.

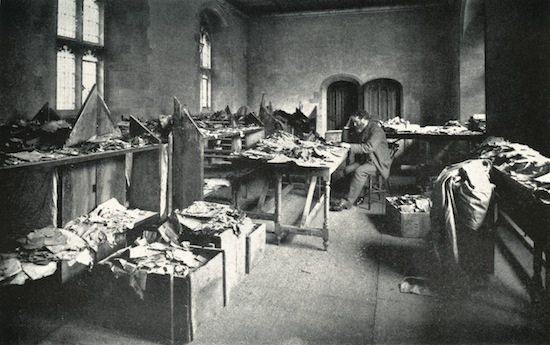

One of the most amazing finds from the post-pharaonic period was made in Cairo, when a 19th century researcher found a huge cache of texts in the genizah (sacred storeroom) of Ben Ezra Synagogue. In Jewish tradition, paper with writing on it cannot be thrown away in case it includes portions of religious writing or the name of God. Instead they have to be disposed in a special ritual. There’s a similar tradition in Islam. My cleaning lady in Tangier, for example, burns any paper I put in the dustbin rather than throw it out. I’ve taken to leaving any paper in a respectful stack next to the dustbin instead of putting it inside with the banana peels.

Good thing my cleaning lady didn’t have access to Ben Ezra Synagogue. For some reason the storeroom was never cleared out and accumulated more than 200,000 documents. Most date from the 11th to the 13th centuries AD and are written in Hebrew, Judeo-Arabic, Aramaic, and Arabic. They include everything from court cases to business receipts and originate from as far away as Spain and India, showing just how important the land of Egypt remained centuries after the last pharaoh was laid in his tomb.

Egypt: Faith After The Pharaohs runs until February 7.

Sean McLachlan is a freelance travel and history writer. He is the author of the historical fantasy novel A Fine Likeness, set in Civil War Missouri, and the post-apocalyptic thriller Radio Hope. His historical fantasy novella The Quintessence of Absence, was published by Black Gate. Find out more about him on his blog and Amazon author’s page.