Needling at Society’s Wounds: Horror in Pop Culture, From the 1950s to True Detective

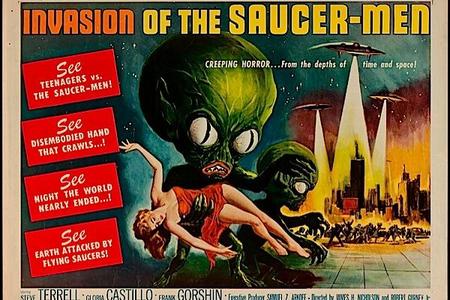

It appears near impossible to pinpoint what drives popular culture as it develops. If you look back through science fiction and horror of the nineteen fifties, you can hone in on Cold War undertones in retrospect, on the painful obviousness of America’s paranoia during its long conflict with the USSR. Fiction, and especially genre fiction, is a sponge for social anxieties. Horror in particular, since it thrives on fear, excels at needling at society’s wounds.

It appears near impossible to pinpoint what drives popular culture as it develops. If you look back through science fiction and horror of the nineteen fifties, you can hone in on Cold War undertones in retrospect, on the painful obviousness of America’s paranoia during its long conflict with the USSR. Fiction, and especially genre fiction, is a sponge for social anxieties. Horror in particular, since it thrives on fear, excels at needling at society’s wounds.

One need only turn to the seventies, as America moved beyond the optimism of the previous decade into a chilly, post-Summer of Love winter, to see the dynamic at play. The horror fiction during that time is so spectacular precisely because of how it responded to the decaying optimism of the previous generation. With the dream of Civil Rights leading to widespread racial inequality, with the closure of Vietnam, the introduction of long feather haircuts, the dissolution of the Beatles, and the rise of disco, society was wide open for big budget, socially scathing works of terror.

The eighties turned towards renewal and perceived stability, creating prolonged franchises and creature features that intermixed humor and gore with boatloads of camp. The nineties brought forth a self-referential realism that, in this author’s opinion, accompanied the economic boom of the Clinton years, where pre-9-11 excess bubbled in size and gave way to less politically indulgent modes of entertainment. In the current moment, however, in the wake of terrorism, global economic crisis, and two wars, one thing seems abundantly clear: we’ve returned to championing bleakness in pop culture that feels in many ways similar to what was seen in the seventies. But bleakness weaned on a new generation of plenty that can make the convention feel plastic, and even hypocritical, in nature.

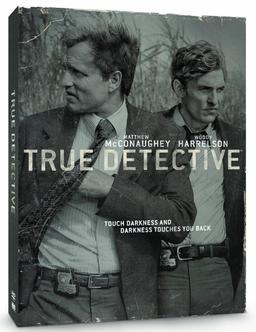

It can be argued that Earth is in less a state of abject chaos than it ever has been since humans began establishing their reign over it. And yet, a great deal of popular science fiction, horror, fantasy, and anything in between is reliant on a finely tuned doom engine, in which narratives rely on various degrees of nihilism as a crutch. After Game of Thrones and The Walking Dead primed the American public for existential dread with its brutal subversions of traditional narratives and its tendency to kill off beloved characters in a manner that would have made Samuel Beckett grin with delight, True Detective (season one, anyhow) mainstreamed the sentiment, riffing off Thomas Ligotti and Robert Chambers until Yellow King memes made their way to t-shirts, and the Nietzschean Perspectivist Rusty Cole became a popular Halloween costume.

It can be argued that Earth is in less a state of abject chaos than it ever has been since humans began establishing their reign over it. And yet, a great deal of popular science fiction, horror, fantasy, and anything in between is reliant on a finely tuned doom engine, in which narratives rely on various degrees of nihilism as a crutch. After Game of Thrones and The Walking Dead primed the American public for existential dread with its brutal subversions of traditional narratives and its tendency to kill off beloved characters in a manner that would have made Samuel Beckett grin with delight, True Detective (season one, anyhow) mainstreamed the sentiment, riffing off Thomas Ligotti and Robert Chambers until Yellow King memes made their way to t-shirts, and the Nietzschean Perspectivist Rusty Cole became a popular Halloween costume.

Even when it comes to superhero franchises, grim hopelessness comes part and parcel with 21st century mainstream thought. Though such narratives end up triumphant, the trope of bleakness, of non-existence, of omni-apocalyptic gloom is sprinkled (or heaped) on much of what media we consume. At a time when technology is becoming ubiquitous, world hunger and poverty are decreasing, and war casualties are at their lowest point in recorded history, our entertainment would have one think that we are on the brink of not just social, but mental collapse, subsumed in what has given way from anxiety into malaise.

This isn’t to say that this bleakness trend is a bad thing, and even if it was, we wouldn’t be able to say so until a couple decades pass and we decided to look back. But there is something about it that is starting to come off as unserious. One need only look at season two of True Detective to see how difficult it became to belabor the same principals of nihilism that were strewn throughout the first.

Partly this was the fault of the writing, which, like a cake baked backwards, came out mutant and unappetizing. But partly this was because of the possibility that the grim illusion of perpetual meaninglessness can’t hold up as a trope. Because, in many ways, the idea of a modern American public attempting to present themselves as physically downtrodden, as spiritually and emotionally vacuous, as living in an age of reoccurring apocalypse and perpetual suffering, has some merits, but, in comparison to other global societies, is somewhat perplexing, and even patronizing. This isn’t to purport that Americans are problem free, that ISIS isn’t a nihilistic death-cult, that school shootings don’t demoralize our very beings, and that some regions of the world are embroiled in war. But I would argue that we should be more judicious about the way in which we cheapen existentialism, nihilism, and apocalypse by turning them into tropes. For once something becomes a trope, it enters the realm of fabrication.

Partly this was the fault of the writing, which, like a cake baked backwards, came out mutant and unappetizing. But partly this was because of the possibility that the grim illusion of perpetual meaninglessness can’t hold up as a trope. Because, in many ways, the idea of a modern American public attempting to present themselves as physically downtrodden, as spiritually and emotionally vacuous, as living in an age of reoccurring apocalypse and perpetual suffering, has some merits, but, in comparison to other global societies, is somewhat perplexing, and even patronizing. This isn’t to purport that Americans are problem free, that ISIS isn’t a nihilistic death-cult, that school shootings don’t demoralize our very beings, and that some regions of the world are embroiled in war. But I would argue that we should be more judicious about the way in which we cheapen existentialism, nihilism, and apocalypse by turning them into tropes. For once something becomes a trope, it enters the realm of fabrication.

I personally enjoy a lot of entertainment being produced at this current moment. Because of the fact that we’re in a time of cultural decay and increased political vehemence, fiction, particularly horror fiction, is given a chance to thrive, peeling away at mainstream sensibilities and attitudes. Post-apocalyptic fiction is at an all time high, with hundreds upon thousands of works being produced annually. I’m enamored with many of them, and am creating something of one myself, so in many ways, I’m very much contributing to the culture I’m criticizing.

But I also think it’s worth examining our obsessions so that, as time goes on, we make sure not to lapse into caricature. Our society is one in which advancement is the norm, in which, despite political setbacks, inequality, and tragedy, privilege runs rampant through our ranks, informing everything we understand as real. Without seeing that, we run the risk of cheating ourselves, something that, in effect, renders things truly meaningless.

Samuel Sattin is a novelist and essayist. He is the author of the new novel The Silent End and League of Somebodies, which was described by Pop Matters as “One of the most important novels of 2013.” His work has appeared in The Atlantic, Salon Magazine, io9, Kotaku, Publishing Perspectives, The Weeklings, The Rumpus, The Good Men Project, Litreactor, San Francisco Magazine, SF Signal, Buffalo Almanack, and elsewhere. Also an illustrator, he holds an MFA in Comics from California College of the Arts and has a creative writing MFA from Mills College. He’s the recipient of NYS and SLS Fellowships, and is represented by Dara Hyde at Hill Nadell Literary Agency. His website is samuelsattin.com. He lives in Oakland, California.

I don’t have anything to add to your analysis but my own anecdotal perspective:

I personally am tired of nihilistic themes in popular culture. Since its premiere over five years ago, this is the first year I will not be watching The Walking Dead. I also don’t plan on watching any more Game of Thrones episodes either. Why? I think both have become boring. They pretty much re-tread the same things that they do before.

I would love to see an episode of WD where the focal group actually runs into a group of genuinely good people. I would also love to see an episode of GoT where someone is actually a true hero without some sort of gray-ish morality motivating them.

I’m all for realism; but there’s fine line between that and pessimism. And right now, I’m a bit sick of dark side.

I didn’t watch the second season of True Detective…because of the first season of True Detective. There was so much to like in that initial season, but ultimately, I felt that the show lost its nerve.

I don’t believe in dark for dark’s sake – I like happy endings. I just didn’t feel that TD earned it’s surprisingly upbeat conclusion. To remain honest, that show needed to end dark. All along it presented itself as “not the same old thing”, and what happens at the end? Cole is pulled back into humanity through a near-death experience in which he feels the love of his dead daughter waiting for him. (?!) I suddenly felt as if I were watching an episode of Quincy.

In the end, having created the nihilistic Rust Cole, the creators discovered that character was a check they were unable – or unwilling – to cover.

I also think it’s a very pertinent that, as you point out, all this bleakness is coming out of the developed West, the world’s equivalent of Disneyland. As George Orwell said somewhere, “People with empty bellies never despair of the universe.”

TP: “As George Orwell said somewhere, ‘People with empty bellies never despair of the universe.'”

Orwell has a point: you need leisure time from fighting for basic survival to do much philosophical navel-gazing. That being said, nihilism is hardly unique to the West or to the middle class and well-to-do. It comes up in much of the world’s literature, ancient, medieval, and modern.