Fantasia Diary 2015, Day 18: Ava’s Possessions, The Golden Cane Warrior, H., and Turbo Kid

Friday, July 31, started late for me at Fantasia. My first movie, a horror-comedy called Ava’s Possessions, screened at the Hall Theatre at 5:15. After that I decided to watch the Indonesian wuxia movie The Golden Cane Warrior. Then I’d go across to the De Sève Theatre to catch the surreal science-fictional American-Argentinian movie H. before returning to the Hall for the Friday midnight movie, a Quebec-made tribute to 80s post-apocalypse action movies called Turbo Kid. That would carry me through to something like 2 AM. So if things started late, at least it looked like I had a lot on the agenda.

Friday, July 31, started late for me at Fantasia. My first movie, a horror-comedy called Ava’s Possessions, screened at the Hall Theatre at 5:15. After that I decided to watch the Indonesian wuxia movie The Golden Cane Warrior. Then I’d go across to the De Sève Theatre to catch the surreal science-fictional American-Argentinian movie H. before returning to the Hall for the Friday midnight movie, a Quebec-made tribute to 80s post-apocalypse action movies called Turbo Kid. That would carry me through to something like 2 AM. So if things started late, at least it looked like I had a lot on the agenda.

The festival experience began even before the movies, in a way. One of the interesting things about Fantasia is the way you meet people in line, strike up conversations, and often get to know new acquaintances over the course of the festival. In line for Ava’s Possessions I got to speak to a teenager from France — who turned out to be a director. 16-year-old Nathan Ambrosioni was only 14 years old when he directed his feature debut, Hostile, which was having its international premiere at Fantasia. I made a note of the film, though since I was trying to focus on fantasy and science-fiction I suspected I wouldn’t be able to get around to seeing a thriller; still, it sounded interesting. At which point the theatre opened, and the crowd took its seats to the sounds of Black Sabbath, played by the CJLO DJs.

It was a good choice of intro music. Ava’s Possessions, written and directed by Jordan Galland, is about the aftermath of a demonic possession. It follows a New Yorker named Ava (Louisa Krause), who at the start of the movie wakes up to find out that she’s spent the past month as the host for a demon named Naphula the Annointed. Her friends can’t relate to her experience — “Was it kinda like being pregnant? Having this thing inside you?” — but that’s far from the worst of it. Her goldfish are dead, nobody called the record company where she works to them she was sick, and she’s facing criminal charges for the acts Naphula committed while in her body. She’s legally obliged to join a twelve-step program for people who’ve been possessed, Spirit Possession Anonymous; and part of the homework the program director (Wass Stevens) gives her is to find out what happened when the demon was in control of her, and try to make it up to those she wronged. Except it soon becomes clear something complex and sinister took place during that month, something that left a disturbing amount of blood in her apartment.

It’s a good set-up for a mix of horror, comedy, and mystery. Or, put another way: it’s a good set-up for an urban fantasy. It’s not quite a paranormal romance, though Ava’s love life is a sub-plot. But it’s a story set in a world where supernatural elements have become normalised, following a young career woman with a sharp sense of humour. And it’s a good story, too. The humour works, and the mystery’s solid. There is a sub-plot that builds to the inevitable last-scene horror-movie twist that’s visible a mile off; but then that twist itself can be interpreted a couple of different ways, I think.

It’s a good set-up for a mix of horror, comedy, and mystery. Or, put another way: it’s a good set-up for an urban fantasy. It’s not quite a paranormal romance, though Ava’s love life is a sub-plot. But it’s a story set in a world where supernatural elements have become normalised, following a young career woman with a sharp sense of humour. And it’s a good story, too. The humour works, and the mystery’s solid. There is a sub-plot that builds to the inevitable last-scene horror-movie twist that’s visible a mile off; but then that twist itself can be interpreted a couple of different ways, I think.

What I mean by that is this: most of the movie’s about Ava trying to get her life back together, rebuilding her connections with her family and friends to be as good or better than they were before the possession. It’s not easy, she faces obstacles and sometimes makes mistakes, but that’s the outline of the story. The main action of the plot’s resolved, we see her go on, and then we have the final shots which resolve the sub-plot hinted at throughout the movie. And the very last frames, I feel, can be read in two very distinct ways: either Ava’s succeeded in mastering the demonic forces that claimed her before, or that mastery’s only an illusion. In other words, you can read the end as the end either of an urban fantasy story or of a horror movie. She’s become fully empowered, reconciled to strange powers within her — or she never had a chance.

What I mean by that is this: most of the movie’s about Ava trying to get her life back together, rebuilding her connections with her family and friends to be as good or better than they were before the possession. It’s not easy, she faces obstacles and sometimes makes mistakes, but that’s the outline of the story. The main action of the plot’s resolved, we see her go on, and then we have the final shots which resolve the sub-plot hinted at throughout the movie. And the very last frames, I feel, can be read in two very distinct ways: either Ava’s succeeded in mastering the demonic forces that claimed her before, or that mastery’s only an illusion. In other words, you can read the end as the end either of an urban fantasy story or of a horror movie. She’s become fully empowered, reconciled to strange powers within her — or she never had a chance.

It’s a fascinating conclusion to a very good movie. Ava’s Possessions has a tremendously effective approach to worldbuilding, a slightly cynical air that goes a long way to building a real-feeling New York City. The twelve-step group has the familiar iconography of self-help groups seen in any number of other shows, but with some distinct touches of its own. And those touches in turn help build the reality of the world. We get hints of how powerful magic really is, in the intensity of Stevens’ character, or in the occult shop run by a heavily-scarred Carol Kane. The movie has its own demonic logic, and follows that logic remorselessly.

It’s a fascinating conclusion to a very good movie. Ava’s Possessions has a tremendously effective approach to worldbuilding, a slightly cynical air that goes a long way to building a real-feeling New York City. The twelve-step group has the familiar iconography of self-help groups seen in any number of other shows, but with some distinct touches of its own. And those touches in turn help build the reality of the world. We get hints of how powerful magic really is, in the intensity of Stevens’ character, or in the occult shop run by a heavily-scarred Carol Kane. The movie has its own demonic logic, and follows that logic remorselessly.

More than that, it plays with what demonic possession means. Demons here have an abusive relationship with their human hosts. Ava was lucky that Naphula was only a kind of joyrider. She meets one woman at the self-help group who wants her demon back: “I think it was special for him too,” she reflects. “I was the first girl he’s ever been inside of, in that way.”

But then demons are also more internal. They’re addictions. Ava’s mother asks if she’s still smoking marijuana: “It’s a gateway drug,” she warns. Ava for her own part is disgusted to find that she’s being blamed for something out of her control, and it’s hard not to feel like she’s got a point. But how much of the demonic possession derived from something inside her? How much was the possession her letting out something she’d been repressing? Demons in this movie can also be read as the Jungian shadow. Ava learns how to deal with that shadow-self, rather than try to confine it within a facade of control.

But then demons are also more internal. They’re addictions. Ava’s mother asks if she’s still smoking marijuana: “It’s a gateway drug,” she warns. Ava for her own part is disgusted to find that she’s being blamed for something out of her control, and it’s hard not to feel like she’s got a point. But how much of the demonic possession derived from something inside her? How much was the possession her letting out something she’d been repressing? Demons in this movie can also be read as the Jungian shadow. Ava learns how to deal with that shadow-self, rather than try to confine it within a facade of control.

Or does she? As I say, it’s a movie that can be interpreted different ways. It’s clever enough to explore different meanings of possession — Ava also starts the movie concerned with material things, making the title a pun — and to have an ending both effective and ambiguous. Along the way there’s some gore, some effective comedy, and a solid mystery. The cinematography is strong, with dark shadows and rich colours building a noirish sense. In my opinion, the movie’s more interesting as urban fantasy than horror. But it works either way.

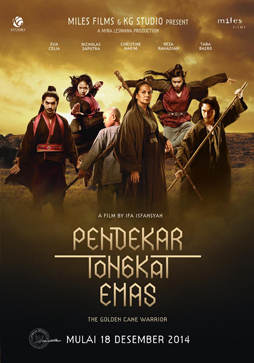

The Golden Cane Warrior (originally Pendekar Tongkat Emas) was a change of pace. Directed by Ifa Isfansyah from a script he co-wrote with Mira Lesmana and Jujur Prananto, it’s set in Indonesia’s past, as a great martial artist named Cempaka (Christine Hakim) prepares to pass on her most potent technique. She selects a young woman named Dara (Eva Celia Latjuba) from among her four pupils to receive the secret knowledge, but two of her elder students, Biru (Reza Rahadian) and Gerhana (Tara Basro), rebel. This begins a series of battles, intrigues and death that pulls in a mysterious outsider named Elang (Nicholas Saputra) with an unsuspected connection to Cempaka.

The Golden Cane Warrior (originally Pendekar Tongkat Emas) was a change of pace. Directed by Ifa Isfansyah from a script he co-wrote with Mira Lesmana and Jujur Prananto, it’s set in Indonesia’s past, as a great martial artist named Cempaka (Christine Hakim) prepares to pass on her most potent technique. She selects a young woman named Dara (Eva Celia Latjuba) from among her four pupils to receive the secret knowledge, but two of her elder students, Biru (Reza Rahadian) and Gerhana (Tara Basro), rebel. This begins a series of battles, intrigues and death that pulls in a mysterious outsider named Elang (Nicholas Saputra) with an unsuspected connection to Cempaka.

It’s a well-shot movie, very dark and atmospheric, with plenty of lush natural settings. It has a rich soundtrack. And it’s well-plotted, focussing on a small group of characters but including a larger society that their struggles affect. All these things are good.

But there’s no humour in the movie that I noticed, and the pacing is very deliberate. Rather than develop an introspective feel, for me it simply felt slow. I have no idea how much this is a function of cultural expectations. All I can say is that for me as a viewer, the film dragged. It did not feel bloated, nor did it feel vacuous; it had things on its mind, and it had a well-developed narrative it was intent on working out. But collectively it didn’t seem to find any momentum.

There are relatively few fights in the movie, most of them small-scale battles between a handful of people. When they come, they’re well-done. The pace picks up, as though the film has finally found its centre of interest. The individual styles come out in battle, and the choreography’s solid. The fighting, then, serves to highlight the themes of the movie.

Which makes sense. The film tries to speak about fighting and the nature of combat. There’s minimal fantasy here, and no extravagant imaginative settings. The story’s focussed on warriors, some of whom are trying to do the right thing, and some of whom are out for themselves. There are lots of philosophical ponderings about war and fighting and what is right. When one character makes a crucial decision to break an oath he reflects: “the interests of the majority are greater than my own.” The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few, or the one.

Which makes sense. The film tries to speak about fighting and the nature of combat. There’s minimal fantasy here, and no extravagant imaginative settings. The story’s focussed on warriors, some of whom are trying to do the right thing, and some of whom are out for themselves. There are lots of philosophical ponderings about war and fighting and what is right. When one character makes a crucial decision to break an oath he reflects: “the interests of the majority are greater than my own.” The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few, or the one.

Still, in all the villains are most sympathetic. Rahadian and especially Basro play their characters with energy, and make for some of the most watchable parts of the film. The drama of the heroes, by comparison, seems to lack urgency. You see what they want, you see how it all connects logically, but it lacks life. For an action movie there’s a curious lack of exuberance. Overall the young cast are engaging. Certainly they handle the action scenes well, especially the movie’s long final fight. That battle’s the point the whole movie’s been heading toward, and it pays off handsomely. But at 111 minutes, it takes a while to get there. It’s a watchable movie, but at least to me, the pacing’s an issue.

From there I went over to the De Sève to watch H., which was preceded by a Finnish short called “Reunion,” originally “Tuolla puolen”. Written and directed by Janne Reinikainen and Iddo Soskolne, it’s set in a small northern town where a little girl (Riitta Havukainen) can see deaths coming. She’s waiting for a reunion with her brother (Janne Reinikainen), who she loves, but who has turned into a wreck of a man after an accident years before. It’s a touching movie, shot with a cold clarity that recalls Let the Right One In, acted nicely with subdued humour, and coming together at the end in a way both heart-breaking and cheerful.

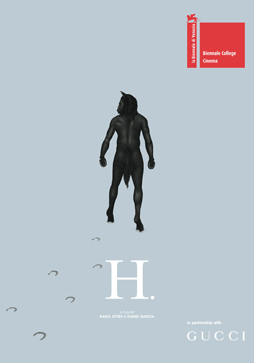

H. was another change of pace again. Directed and written by Rania Attieh and Daniel Garcia, it’s set in contemporary Troy, New York, and parallels the stories of two different couples as strange events that may portend an alien invasion afflict the town. The first couple is an older wife and husband, Helen (Robin Bartlett) and Roy (Julian Gamble); Helen’s obsessed with her “reborn doll,” a realistic baby doll she pampers and feeds like a human child. Roy’s dour but accepting. Until he vanishes. Meanwhile, two married artists in their thirties are expecting a baby of their own: the second Helen of this Troy (Rebecca Dayan) is four months pregnant with Alex’s child — and then a meteor passes over the town, and weirdness ensues that may represent aliens infiltrating Troy.

H. was another change of pace again. Directed and written by Rania Attieh and Daniel Garcia, it’s set in contemporary Troy, New York, and parallels the stories of two different couples as strange events that may portend an alien invasion afflict the town. The first couple is an older wife and husband, Helen (Robin Bartlett) and Roy (Julian Gamble); Helen’s obsessed with her “reborn doll,” a realistic baby doll she pampers and feeds like a human child. Roy’s dour but accepting. Until he vanishes. Meanwhile, two married artists in their thirties are expecting a baby of their own: the second Helen of this Troy (Rebecca Dayan) is four months pregnant with Alex’s child — and then a meteor passes over the town, and weirdness ensues that may represent aliens infiltrating Troy.

H. is in many ways a baffling movie. We get small-scale gravity reversals, people going out into the woods like sleepwalkers, a mysterious black horse (presumably a Trojan horse) that is sometimes a man with a horse’s head, and repeated shots of a massive stone head floating down a river. There is ultimately no explanation for most of these things. They’re symbols, but symbols with no plot meaning attached — and, too often, no thematic weight.

Structurally the two stories don’t really connect, except in a sort of coda at the movie’s very end. They’re told in alternating quarters of the film, with what seems to be minimal thematic interplay for most of the movie’s running time. The conceit of having two Helens of Troy is left unexamined, and indeed uncommented-on.

Given all this, one would expect the movie would be an utter failure. I do think it’s a failure, but not necessarily a total failure. Even when details are baffling, there’s an attention to atmosphere and emotional reaction that helps anchor the viewer. That starts with the visual sense and the film’s technique. The filmmakers have talked about trying to emulate classical European filmmaking, and that’s readily visible. The studied framing has a cool, detached sense that paradoxically brings out the characters’ emotions: it’s as though they’re being examined like specimens under a microscope.

The atmosphere of the two different households is built up assuredly. The homes of the Helens are architecturally distinct and shot very differently, one emphasising the decayed warmth of an older house of wood and brick, the other the cool surface of an elegant modernist apartment — in both cases, exactly the right home for the people who live in them, architecture bringing out character. But of course there’s much more than that: the way the couples relate to each other is utterly precise. Every line of dialogue hints at tensions or old sorrows. Every confident statement hides irony. In a film that’s nominally science fiction, the details of human relationships are what’s most effective.

The atmosphere of the two different households is built up assuredly. The homes of the Helens are architecturally distinct and shot very differently, one emphasising the decayed warmth of an older house of wood and brick, the other the cool surface of an elegant modernist apartment — in both cases, exactly the right home for the people who live in them, architecture bringing out character. But of course there’s much more than that: the way the couples relate to each other is utterly precise. Every line of dialogue hints at tensions or old sorrows. Every confident statement hides irony. In a film that’s nominally science fiction, the details of human relationships are what’s most effective.

Which is actually a problem, in that the story is by comparison unclear and diffuse. So while the characters’ emotions are well-defined at the start, that solid beginning ends up wasted. They react to strange things as they occur, but I can’t see an arc or development. The older Helen’s attachment to her lifelike doll is wonderfully touching, creepy, and sad all at once — but it comes to nothing, because you can’t see how events in the movie connect up logically.

The movie’s consciously trying to claim a parallel with a myth, but itself lacks any sort of mythic clarity. These Helens don’t have a simple narrative trajectory. Things don’t happen directly because of what they do, or not that I can see. There’s no flatness — the original Helen was the incarnation of a very simple idea: the most beautiful woman in the world. Whatever’s happening here, there is no equivalent directness. Nor does the story of the film seem to hold any obvious parallels. There aren’t any immediate equivalents to Paris or Menelaus. If there are aliens representing a horde of Greeks, they’re fairly restrained; I have to assume the black horse is a version of the Trojan Horse, but I don’t see the connection. So by the end of the movie, the relatively clever idea of having Helens of Troy, New York, is wasted by leaving the myth unexplored.

The movie’s consciously trying to claim a parallel with a myth, but itself lacks any sort of mythic clarity. These Helens don’t have a simple narrative trajectory. Things don’t happen directly because of what they do, or not that I can see. There’s no flatness — the original Helen was the incarnation of a very simple idea: the most beautiful woman in the world. Whatever’s happening here, there is no equivalent directness. Nor does the story of the film seem to hold any obvious parallels. There aren’t any immediate equivalents to Paris or Menelaus. If there are aliens representing a horde of Greeks, they’re fairly restrained; I have to assume the black horse is a version of the Trojan Horse, but I don’t see the connection. So by the end of the movie, the relatively clever idea of having Helens of Troy, New York, is wasted by leaving the myth unexplored.

More than that: the movie opens and closes with epigrams about Troy, neither from Homer. The first is “Everything is more beautiful because we are doomed. You will never be lovelier than you are now. We will never be here again.” As far as I can tell, this is not actually from The Iliad, but from the 2004 movie Troy. The closing quote is “Ilium was, Tory is,” a translation of “Ilium fuit, Troja est,” the motto of Troy, New York. I mention these things because they seem to reflect the occasionally slapdash nature of the film: myth used without understanding.

More than that: the movie opens and closes with epigrams about Troy, neither from Homer. The first is “Everything is more beautiful because we are doomed. You will never be lovelier than you are now. We will never be here again.” As far as I can tell, this is not actually from The Iliad, but from the 2004 movie Troy. The closing quote is “Ilium was, Tory is,” a translation of “Ilium fuit, Troja est,” the motto of Troy, New York. I mention these things because they seem to reflect the occasionally slapdash nature of the film: myth used without understanding.

It’s a very real pity. H. is one of those movies I’d like to be good. It’s visually engaging, successfully creates some effective moments, and establishes strong emotional atmospheres quickly and subtly. But the narrative’s incoherent, and the symbols lack weight. The older Helen has a simpler story, and is particularly well-played (though seeming in the end to owe more to Isis than Helen). But the younger Helen’s story doesn’t make any particular sense: it’s a bunch of things that happen. Overall, H. has the skin of a good movie, but lacks much else — muscle, heart, or skeletal structure.

With that over with, I returned to the Hall Theatre, and what turned out to be a long wait — the movie before Turbo Kid was running a bit long. I ended up in another Fantasia line-up chat. I met filmmaker Richard Karpala, whose short film “Iris” was playing at Fantasia; it would go on to win the Bronze Prize in the Best Short Film category of the festival’s audience awards. At one point I asked Karpala why he got into film as a storytelling form, and he answered that a better question was why stay in it, which I thought was interesting. Also killing time in line was one of the producers behind the Mexican crime-thriller movie Scherzo Diabolico, who mentioned that he was working on a fantasy project called Are We Not Cats? — and had been hearing from people in the industry telling him that was a bad title because it’s got a question mark in it. Also in the chat was Robin Bougie, a cheerful pornographer and publisher of Cinema Sewer magazine, who told stories about making an x-rated version of the gospel story as we took our seats and waited for the movie to start. It was, all told, the perfect conversation to set up a midnight movie.

With that over with, I returned to the Hall Theatre, and what turned out to be a long wait — the movie before Turbo Kid was running a bit long. I ended up in another Fantasia line-up chat. I met filmmaker Richard Karpala, whose short film “Iris” was playing at Fantasia; it would go on to win the Bronze Prize in the Best Short Film category of the festival’s audience awards. At one point I asked Karpala why he got into film as a storytelling form, and he answered that a better question was why stay in it, which I thought was interesting. Also killing time in line was one of the producers behind the Mexican crime-thriller movie Scherzo Diabolico, who mentioned that he was working on a fantasy project called Are We Not Cats? — and had been hearing from people in the industry telling him that was a bad title because it’s got a question mark in it. Also in the chat was Robin Bougie, a cheerful pornographer and publisher of Cinema Sewer magazine, who told stories about making an x-rated version of the gospel story as we took our seats and waited for the movie to start. It was, all told, the perfect conversation to set up a midnight movie.

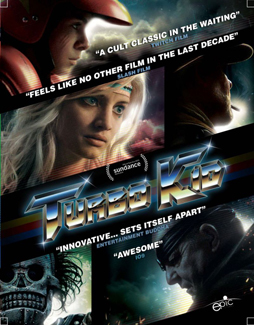

Turbo Kid, a local Montréal product that had its start at Fantasia’s International Co-Production Market, is an homage to low-budget 80s sci-fi post-apocalypse action films. It takes place after the apocalypse in the far-flung future year 1997. We follow a comic-book loving teen known only as the Kid (Munro Chambers) who lives in a bunker and trades what he scrounges from junk heaps for water and other necessities. Then he meets a bright-eyed but strange girl named Apple (Laurence Leboeuf). Then she’s captured by the sadistic ruler of the wasted land, Zeus — played, inevitably, by Michael Ironside. The Kid finds a suit of body armour with a high-tech weapon attached, and sets off to rescue her. Which starts a long-running battle with Zeus leading to an explosive climax.

Written and directed by François Simard, Anouk Whissell, and Yoann-Karl Whissell, Turbo Kid’s frantic and chaotic, but overall fun. It gets the tone right, which is crucial: knowing, but not too arch. There’s an odd warmth to it, in fact, which sits oddly next to the vast amounts of blood. But then again, the gore’s impossible to take seriously — if other movies have geysers of blood, Turbo Kid is what happens when the Hoover Dam cracks. It’s the bloodshed equivalent of Monty Python’s vomiting Mister Creosote: it just goes and goes and never stops. Hands are cut off, characters chopped in two (or in four), and generally hacked to bits; yet somehow there’s a cheerfulness to the film despite it all.

In fairness, I have to say that I may be being influenced by the crowd reaction. The audience for Turbo Kid loved it from start to finish. I noted one of the review quotes on the film’s poster calls it “the ultimate midnight movie,” and that’s a fair assessment. I saw it play out that Friday night. If it’s not terribly profound, there’s no doubt Turbo Kid’s exactly the sort of funny, bloody, fast-paced film that works as a midnight movie.

In fairness, I have to say that I may be being influenced by the crowd reaction. The audience for Turbo Kid loved it from start to finish. I noted one of the review quotes on the film’s poster calls it “the ultimate midnight movie,” and that’s a fair assessment. I saw it play out that Friday night. If it’s not terribly profound, there’s no doubt Turbo Kid’s exactly the sort of funny, bloody, fast-paced film that works as a midnight movie.

Which is to say that the humour works. There are a lot of cheap gags, but they’re sold well. And there’s a streak of absurdity that runs through it, often impossible to describe. When the Kid improvises a weapon for Apple by duct-taping a small garden gnome to a piece of wood, Apple’s in heaven at her “GNOME STICK!” It plays out brilliantly on screen, as the actors seize the humour in the gag. Turbo Kid works because it consistently gets that kind of lunacy across, the sort of thing that it’s hard to explain to people in the cold light of day.

As a story, it works without being surprising — we get a tough-guy ally, Frederic, to give the Kid a role model; flashbacks to the Kid’s childhood and the death of his parents; a climactic confrontation with Zeus and his assortment of weirdly-dressed henchcreatures. The performances aren’t subtle, but exactly on the nose in a good way: they carry you through the film, making you interested in seeing the actors on the screen. Overall the movie’s not a radical reinvention of its form, but works because of the constant sense of fun and the sense of invention in the post-apocalypse world it creates. This isn’t a high-budget world, but the movie builds something coherent out of run-down factories and gritty dried-up soil and poisonous junkyards; it’s all very appropriate for a movie paying homage to low-budget films shot in quarries.

There’s a great 80s-style synthesizer soundtrack, helping to tie together the visuals, and that too fits perfectly. This is a world of old Sony walkmans and comic books and chainsaws and ludicrous violence. It finds the sweet spot between homage and parody, and works it mercilessly; imagine a Kids in the Hall skit extended to feature length and you may be in the area.

There’s a great 80s-style synthesizer soundtrack, helping to tie together the visuals, and that too fits perfectly. This is a world of old Sony walkmans and comic books and chainsaws and ludicrous violence. It finds the sweet spot between homage and parody, and works it mercilessly; imagine a Kids in the Hall skit extended to feature length and you may be in the area.

Does it work for people who don’t have a soft spot for the films it’s homaging? Does it work for people who like some of those movies, but aren’t inherently interested in the buckets-of-blood aesthetic? Probably not. It’s got a specific audience, and goes after them relentlessly. It’s not aiming particularly high. But it does what it sets out to do.

A question-and-answer period in French followed the film, as the three writer/directors took the stage. Asked where it was shot, the filmmakers said it was in the town of Thetford Mines, Quebec, formerly known for its production of asbestos. They revealed there are talks underway to put out a VHS edition of Turbo Kid. When a questioner asked how the movie ended up co-produced with a New Zealand company, the filmmakers briefly discussed the process of finding funding and the Fantasia marketplace, which they likened to speed-dating only with film pitches. They then talked about the positive reception the film had found at festivals, and said a making-of video would be available on the blu-ray release and through itunes.

A question-and-answer period in French followed the film, as the three writer/directors took the stage. Asked where it was shot, the filmmakers said it was in the town of Thetford Mines, Quebec, formerly known for its production of asbestos. They revealed there are talks underway to put out a VHS edition of Turbo Kid. When a questioner asked how the movie ended up co-produced with a New Zealand company, the filmmakers briefly discussed the process of finding funding and the Fantasia marketplace, which they likened to speed-dating only with film pitches. They then talked about the positive reception the film had found at festivals, and said a making-of video would be available on the blu-ray release and through itunes.

With that, I headed home. It had been a fun end to a long day — and I had a big weekend coming up.

(You can find links to all my 2015 Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.