Fantasia Diary 2015, Day 5: Teana: 10000 Years Later, Crimson Whale, and The Shamer’s Daughter

One of the things people don’t tell you about getting older is that the more books you read and movies you see, the more likely you are to see those stories echoed in other stories. The new books and movies you come across remind to you of the older books and movies you already know. Sometimes there’s good reason for that, as artists try to engage in a dialogue with their forebears. Sometimes you’re just seeing things.

One of the things people don’t tell you about getting older is that the more books you read and movies you see, the more likely you are to see those stories echoed in other stories. The new books and movies you come across remind to you of the older books and movies you already know. Sometimes there’s good reason for that, as artists try to engage in a dialogue with their forebears. Sometimes you’re just seeing things.

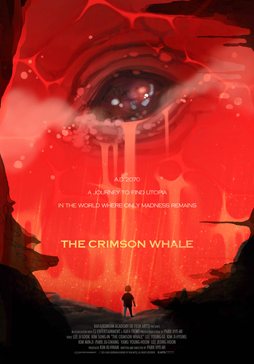

Saturday, July 25, was an interesting series of riddles for me at the Fantasia Festival. I saw three movies that day. Teana: 10000 Years Later is a high science-fantasy 3D CGI animated film from China. Crimson Whale is a traditionally-animated post-apocalypse fable from South Korea. And Denmark’s The Shamer’s Daughter is a live-action adaptation of the first volume of a Danish YA high fantasy. I enjoyed all of them, and saw what seemed to be nods to familiar works within each — though in some cases that might be my imagination running away with me.

Let’s start with Teana (AKA 10000 Years Later, originally Yi wan nian yi hou), which screened at the large Hall Theatre. It’s one of the most visually spectacular movies I’ve seen at Fantasia. Bursting with colour and invention, it moves quickly, introduces a ton of characters, creates a world, and tells an epic story with some very pointed social commentary. I’ve seen some mention online that it’s based on a Tibetan fable, but can find no more specific information than that. Personally, I found myself strongly reminded of The Lord of the Rings, as the film seemed to refer to Tolkien while also inverting certain aspects of his story.

The film was directed by Yi Li, from a script by Yi and Ocean Tree (according to the Fantasia site; another site also credits Nie Shangjie and Liu Yong as writers). The version I saw had an English voice cast, though I can’t find credits for the actors online. Apparently the movie took seven years to make, and I can believe it; there’s an awful lot of imagination and story in this movie, perhaps too much.

The film was directed by Yi Li, from a script by Yi and Ocean Tree (according to the Fantasia site; another site also credits Nie Shangjie and Liu Yong as writers). The version I saw had an English voice cast, though I can’t find credits for the actors online. Apparently the movie took seven years to make, and I can believe it; there’s an awful lot of imagination and story in this movie, perhaps too much.

The movie opens with a wandering balladeer reciting background. Ten thousand years ago the gods of the West — the descendants of the real-world West, who had developed technological power indistinguishable from divinity — created technological power that could destroy the world, and so locked it away, leaving two gods behind to guard the now-forbidden western lands. A thousand years ago one of those gods was betrayed by a man who sought power, now known as the Devil Wu, who gained some of the lost power of the West. Wu was defeated then, but rumours say he’s returning. Rumour, in this case, is quite right.

There are a series of violent raids into the lands of the various tribes. In the wake of the devastation a group of wanderers unites. At a temple which gives them sanctuary they find out how to defeat Wu: the smallest among them has the power to bring them into the mysterious western region, and strike directly at the heart of Wu’s power. But as they embark on this dangerous quest, Wu sends his armies against a city built into a mountain, where the various tribes have rallied against him. The quest into the blasted forbidden lands is intercut with the massive siege of the city.

There are a series of violent raids into the lands of the various tribes. In the wake of the devastation a group of wanderers unites. At a temple which gives them sanctuary they find out how to defeat Wu: the smallest among them has the power to bring them into the mysterious western region, and strike directly at the heart of Wu’s power. But as they embark on this dangerous quest, Wu sends his armies against a city built into a mountain, where the various tribes have rallied against him. The quest into the blasted forbidden lands is intercut with the massive siege of the city.

You might fairly call this plot a little familiar. But the devil here is in the details. To start with, the world of ten thousand years from now is visually spectacular: forests made of giant vegetables, demonic wolves whose skulls burst through their mouths, a library as large as a city which spells out secrets when seen from high above. Cosmic vistas and mass battle scenes play out onscreen like fever-dreams. Dynamic character designs are everywhere — green elves, tiger-women, a rock titan. And: this is one of a number of films at Fantasia that are leading me to rethink my lack of interest in 3D. Here the technique’s used to heighten scale, particularly vertical scale. It’s a movie that can make you dizzy watching it.

In part that’s because of the incredible density of the film. It runs 96 minutes, and covers an awful lot of plot and backstory in doing so. While introducing a sprawling cast. Perhaps as a result, none of the characters feel strongly developed — except to some extent the villain. The devilish Wu has a specific reason for doing the things he does, a specific set of wants and desires. He aims to revive the technological civilization of the past, and thereby become immortal: “Honour and glory belong to those who follow their dreams!” he rants. He’s not sympathetic, but you understand his role in the story.

In part that’s because of the incredible density of the film. It runs 96 minutes, and covers an awful lot of plot and backstory in doing so. While introducing a sprawling cast. Perhaps as a result, none of the characters feel strongly developed — except to some extent the villain. The devilish Wu has a specific reason for doing the things he does, a specific set of wants and desires. He aims to revive the technological civilization of the past, and thereby become immortal: “Honour and glory belong to those who follow their dreams!” he rants. He’s not sympathetic, but you understand his role in the story.

He’s an individualist, who wants to bring back technology even if it means alienating humanity from nature. And this is where I see a give-and-take with Tolkien, who of course was also concerned with the alienation from nature brought by industrialisation. It’s perhaps a slightly different approach from much of what’s been done with Tolkien in Anglophone countries. It’s not necessarily surprising in a Chinese story that protagonists journey to the west (as it were), but it is unlike much Western fantasy to have the west as the bleak and blasted land from which emerge faceless evil armies, here dead white and hot pink. You could argue that Wu’s driven by traditionally Western ideals, and he certainly wants the technological and political power of the West. As in Tolkien, power and industrialisation are evil.

It’s honestly hard for me to tell whether Teana‘s responding to Tolkien’s novels or to Peter Jackson’s movies, or perhaps to both (if either). I did see three shots specifically recalling the LOTR movies — wanderers travel across mountains at the top of the world, an archer runs up on top of a monster to shoot arrows point-blank into its brain, a monster stands on top of an overhang below which the hero cowers — but then there’s also a camera-rotating-around-a-group-of-heroes shot that seems right out of the Avengers. How far do you want to take this game? Go far enough and you can say that the heroes carry powerful magic stones, that they’re trying to prevent an invasion of demons, and a major female character is sacrificed at the end to unite humanity and nature; which all resembles The Elfstones of Shannara. I’d assume that’s coincidence. My point is that assuming influences based on plot similarities risks turning up false positives. But: it also points out, I think, that the movie’s working with a certain kind of material. Some resemblances are going to happen. Thematically it’s clear that the film’s commenting on the modern-day West; at a certain point, specifically during the climactic final battle, it leaves subtlety far behind as Wu brings Western icons to life and sends them to war against his enemies. It all echoes Western fantasy quests, if with a highly distinctive perspective.

It’s honestly hard for me to tell whether Teana‘s responding to Tolkien’s novels or to Peter Jackson’s movies, or perhaps to both (if either). I did see three shots specifically recalling the LOTR movies — wanderers travel across mountains at the top of the world, an archer runs up on top of a monster to shoot arrows point-blank into its brain, a monster stands on top of an overhang below which the hero cowers — but then there’s also a camera-rotating-around-a-group-of-heroes shot that seems right out of the Avengers. How far do you want to take this game? Go far enough and you can say that the heroes carry powerful magic stones, that they’re trying to prevent an invasion of demons, and a major female character is sacrificed at the end to unite humanity and nature; which all resembles The Elfstones of Shannara. I’d assume that’s coincidence. My point is that assuming influences based on plot similarities risks turning up false positives. But: it also points out, I think, that the movie’s working with a certain kind of material. Some resemblances are going to happen. Thematically it’s clear that the film’s commenting on the modern-day West; at a certain point, specifically during the climactic final battle, it leaves subtlety far behind as Wu brings Western icons to life and sends them to war against his enemies. It all echoes Western fantasy quests, if with a highly distinctive perspective.

Visually lush, it has an almost-psychedelic level of invention — maybe too much. Plot points are introduced at a frantic rate. Narrative threads are dropped for extended periods of time. A plethora of characters get lines and screen time, almost all of whom could have used more elaboration. In particular, a group of heroes who’ve had virtually no introduction take a major role during the siege scenes.

Visually lush, it has an almost-psychedelic level of invention — maybe too much. Plot points are introduced at a frantic rate. Narrative threads are dropped for extended periods of time. A plethora of characters get lines and screen time, almost all of whom could have used more elaboration. In particular, a group of heroes who’ve had virtually no introduction take a major role during the siege scenes.

Could the apparent sprawl of character and plot come from an Eastern storytelling structure? Am I reacting to my culturally-determined expectations of story? I don’t know. For the sake of these Fantasia reviews generally it may be worth noting that I can’t claim to be as familiar with non-Western storytelling traditions as I am with Western ideas of story. I’d hope that the reaction a critic from a certain culture has to a work will be relevant at least to other people within that critic’s culture. For what it’s worth, I find that a lot of good stories work outside their specific traditions: the story precedes the structure. Of course, as a viewer (or reader), one wants to avoid forcing works to fit one’s own preconceptions. But then, that’s also something that viewers (or readers) tend to do naturally. I also suspect that as the world grows smaller, artists become more familiar with art and narrative from other cultures, which may then inform their own art.

And that brings me around to talking about the second movie I saw that Saturday, at the smaller De Sève Theatre: the international première of the animated Korean film Crimson Whale (in Korean Hwasangorae). Written and directed by Park Hye-mi, it takes place in Korea in 2070 — more specifically in Busan’s Haeundae District. But this is a future that’s seen society almost collapse following a series of earthquakes. Ha-jin is an orphan girl struggling to survive among drug dealers and thieves and slavers. Arrested and kidnapped and rescued, she ends up with a group of pirates who want to recover some valuable crystals from an island guarded by a monstrous whale. Ha-jin has the gift of calling whales, but certain members of the crew have an agenda of their own, and reason to hate the guardian whale, who supposedly can tell when the island’s treasure is disturbed.

And that brings me around to talking about the second movie I saw that Saturday, at the smaller De Sève Theatre: the international première of the animated Korean film Crimson Whale (in Korean Hwasangorae). Written and directed by Park Hye-mi, it takes place in Korea in 2070 — more specifically in Busan’s Haeundae District. But this is a future that’s seen society almost collapse following a series of earthquakes. Ha-jin is an orphan girl struggling to survive among drug dealers and thieves and slavers. Arrested and kidnapped and rescued, she ends up with a group of pirates who want to recover some valuable crystals from an island guarded by a monstrous whale. Ha-jin has the gift of calling whales, but certain members of the crew have an agenda of their own, and reason to hate the guardian whale, who supposedly can tell when the island’s treasure is disturbed.

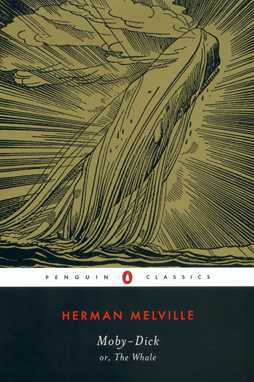

Coming from a movie which appeared to be nodding to The Lord of the Rings, I couldn’t help but see traces of The Hobbit here — the group of thieves who recruit a small but necessary member to sneak treasure out from under the nose of a scaled guardian. But before long a more obvious parallel became clear: the captain of the ship heading to a confrontation with the massive whale lost her arm to the whale in the past, and had a replacement made out of ivory. Instead of telling the story of an obsessive hunter, though, Crimson Whale’s got its mind on other themes. Family, in particular, and the ties that hold people to each other. Like Moby-Dick, the ship at the heart of the story becomes a little world, a society unto itself; but the feel is different, the group smaller and tighter. As part of that group Ha-jin almost reluctantly grows and changes from the tough, prickly orphan. She becomes a part of a thrown-together family, which is ironic as we learn how her biological family exploited her for her gift. But slow-building tensions inevitably come out at the climax, as the crew face the dragon-whale.

The movie’s a treat to look at, particularly in the beginning and ending sections. Post-apocalypse Busan is a white-and-grey world of collapsed skyscrapers, drawn with detail: rebar pokes through fallen concrete, abandoned tires and rubble and graffiti are visible in the background, and grim Ha-jin moves through this world in her outsize coat with hard-eyed determination. Later, the caverns of the whale’s island are warm with heat, organic shapes that burn redder as the crew moves toward the centre. The movement from one setting to the other is natural, earth to fire by way of the sea.

The movie’s a treat to look at, particularly in the beginning and ending sections. Post-apocalypse Busan is a white-and-grey world of collapsed skyscrapers, drawn with detail: rebar pokes through fallen concrete, abandoned tires and rubble and graffiti are visible in the background, and grim Ha-jin moves through this world in her outsize coat with hard-eyed determination. Later, the caverns of the whale’s island are warm with heat, organic shapes that burn redder as the crew moves toward the centre. The movement from one setting to the other is natural, earth to fire by way of the sea.

The characters are developed visually as well. Their design’s highly stylised, but Park’s able to make them say a lot with a turn of the head, a squint of the eyes, an outstretched hand. Dialogue’s minimal, the script tight. The film’s short, at 70 minutes, but plays well: the quietness builds a feeling of characters lost in a world too large for them, dwarfed by elemental forces. Park’s got a fine eye for strong images, not just nice compositions or well-drawn scenes but moments that carry an emotional effect beyond the obvious. Ha-jin scrambling through the ruins, or on a self-pitying bender. A dead porpoise. A switch of art style to carry a flashback that explains Ha-jin’s anger and sense of betrayal. It’s a remarkably assured debut, and an intense film.

After the screening there was a question-and-answer session with Park Hye-Mi. Rupert Bottenberg, the Director of Programming for Fantasia’s Axis section (for animated films), began by asking her what the infrastructure in South Korea was like for animation, and why more animated movies weren’t coming from Korea. Park answered that Koreans have certain ideas of what animation’s for, and specifically expect it to be more family oriented. That said, she knew of several projects currently underway, and said to expect many more strong Korean animated films over the next three or four years. Asked why she brought her film to Fantasia, she said that Fantasia found her film and invited her, that she wanted to show it to foreign audiences, and that she felt the genre focus of Fantasia fit with the post-apocalypse theme of her film.

After the screening there was a question-and-answer session with Park Hye-Mi. Rupert Bottenberg, the Director of Programming for Fantasia’s Axis section (for animated films), began by asking her what the infrastructure in South Korea was like for animation, and why more animated movies weren’t coming from Korea. Park answered that Koreans have certain ideas of what animation’s for, and specifically expect it to be more family oriented. That said, she knew of several projects currently underway, and said to expect many more strong Korean animated films over the next three or four years. Asked why she brought her film to Fantasia, she said that Fantasia found her film and invited her, that she wanted to show it to foreign audiences, and that she felt the genre focus of Fantasia fit with the post-apocalypse theme of her film.

Asked about the inspiration of the movie, Park said that she had always wanted to write about a character who grew and changed over the course of adventures. Her animation professor suggested Moby-Dick to her, and she had always been a fan of post-apocalypse stories, which she said are not particularly present in Korean culture or animation. Asked again about the market for Korean animation, she said again that much Korean animation is for children, and that the government tended to fund series which already existed. Park was then asked about the images of the whale and the volcano, and whether these things had any specific meaning in Korean culture. She said there was nothing in particular, but that she personally had always been fascinated by volcanoes. She did intend a comment on Korean culture, though, in that she felt there were a lot of people in Korea who feel safe, and she wanted to see what Korea would be like if modernity were stripped away.

Park was then asked how long it took her to make Crimson Whale, and what it was like working with what the credits suggested was a small team? She said it was wonderful working with her team, all of whom were the same age and all of whom worked well together and had fun as a group. At the same time, funding for the film was limited. It took a total of two and a half years to make, including a year writing the screenplay. She did not work consistently the rest of the time, but was arranging funding. The last question was what she was working on now, and she said that she was doing work on another director’s movie while working on a post-apocalypse short film.

Park was then asked how long it took her to make Crimson Whale, and what it was like working with what the credits suggested was a small team? She said it was wonderful working with her team, all of whom were the same age and all of whom worked well together and had fun as a group. At the same time, funding for the film was limited. It took a total of two and a half years to make, including a year writing the screenplay. She did not work consistently the rest of the time, but was arranging funding. The last question was what she was working on now, and she said that she was doing work on another director’s movie while working on a post-apocalypse short film.

Now, I’ve been seeing so many movies at Fantasia it’s cut into my time for writing about them, which is why these diary installments are so far behind. In this case, that worked out for the best. Last night, Tuesday the 27th, having already written everything above, I was fortunate enough to speak with Park Hye-mi and ask her a few questions about Crimson Whale. I asked about the resemblance I’d thought I’d seen to The Hobbit, and she said she’d read the book but hadn’t been thinking of it as she worked on the story. She did say that she was generally interested in following the structure of an adventure story, with a character leaving their birthplace and growing as a person through the adventures they had. She also said she was interested in how the crew aboard the small ship in Crimson Whale formed a society, how the adventures brought them together and their relationships grew, which tied in with the movie’s overall theme of family. She said she was generally interested in the social aspects of post-apocalypse stories, and how post-apocalypse fiction became more prominent in bad economic times. She noted that the sense of safety she felt was prominent in Korea was beginning to change in the wake of the Fukushima disaster.

I asked her about her approach to structure in the film, whether she wrote using a Western or Eastern approach to structure, and how Korean films generally were structured. Park said it came down to a matter of personal choice, and that both she and the professor she worked with were fans of the Western three-act structure. At the same time, she pointed out that the Korean perspective would come through regardless of structure; a Korean fan of Old West films was unlikely to write exactly the same kind of western as an American writer, just as an American fan of samurai films wouldn’t write the same film as a Japanese writer. We discussed the way she used Moby-Dick in Crimson Whale, and she observed that her main character, Ha-jin, was originally male. She said that as she worked on the screenplay she tried different combinations and different kinds of relationships between the pirate captain and Ha-jin; at one point she experimented with having a male captain, and a bond to Ha-jin like that between father and daughter. Ultimately, she ended up with two women as the leads. (Earlier, I’d asked her about female characters in Korean films, who — from the very small sample size of a dozen or so Korean movies I’ve seen — seemed to have more prominent roles than in American films. She said that she felt that there had been a lot of sexism within the Korean industry in the past, but that things were changing, as they were changing in the American industry; she mentioned Mad Max: Fury Road as an example of a prominent film centred around women.)

I asked her about her approach to structure in the film, whether she wrote using a Western or Eastern approach to structure, and how Korean films generally were structured. Park said it came down to a matter of personal choice, and that both she and the professor she worked with were fans of the Western three-act structure. At the same time, she pointed out that the Korean perspective would come through regardless of structure; a Korean fan of Old West films was unlikely to write exactly the same kind of western as an American writer, just as an American fan of samurai films wouldn’t write the same film as a Japanese writer. We discussed the way she used Moby-Dick in Crimson Whale, and she observed that her main character, Ha-jin, was originally male. She said that as she worked on the screenplay she tried different combinations and different kinds of relationships between the pirate captain and Ha-jin; at one point she experimented with having a male captain, and a bond to Ha-jin like that between father and daughter. Ultimately, she ended up with two women as the leads. (Earlier, I’d asked her about female characters in Korean films, who — from the very small sample size of a dozen or so Korean movies I’ve seen — seemed to have more prominent roles than in American films. She said that she felt that there had been a lot of sexism within the Korean industry in the past, but that things were changing, as they were changing in the American industry; she mentioned Mad Max: Fury Road as an example of a prominent film centred around women.)

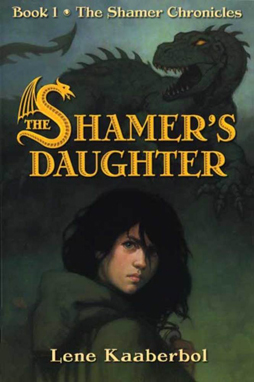

That was last night. Back on Saturday the 18th, after Crimson Whale I crossed the street again to return to the Hall Theatre for Shamer’s Daughter, or Skammerens Datter in the original Danish. Bottenberg presented this film as well, and introduced the movie’s director, Kenneth Kainz, who spoke briefly before the film started. Kainz noted that he spent two and a half years adapting the movie from a book about a “little super-hero” with talents she didn’t want, and how she learned to live with who she is. The movie has the same title as the book, by Lene Kaaberbøl, the first in a four-book series called The Shamer Chronicles; Kaaberbøl’s translated the series into English herself. The movie’s screenplay came from Anders Thomas Jensen.

Dina (Rebecca Emilie Sattrup) lives in a village in the medieval-ish kingdom of Dunark, the daughter of a Shamer, a woman named Melussina (Maria Bonnevie) who can make a person’s most shameful memory take possession of them by locking gazes. When the king and his wife are slain, Melussina’s taken to the capital — then a little later the king’s bastard son Drakan (Peter Plaugborg) returns to Melussina’s hut to take Dina to join her mother. It seems the obvious suspect, the royal heir Nicodemus (Jakob Oftebro), can’t be shamed into a confession of guilt. Is he actually innocent? Or is he utterly unashamed of his crimes? Dina soon finds she’s become involved in a deadly political game, and must struggle to free herself and her mother.

Dina (Rebecca Emilie Sattrup) lives in a village in the medieval-ish kingdom of Dunark, the daughter of a Shamer, a woman named Melussina (Maria Bonnevie) who can make a person’s most shameful memory take possession of them by locking gazes. When the king and his wife are slain, Melussina’s taken to the capital — then a little later the king’s bastard son Drakan (Peter Plaugborg) returns to Melussina’s hut to take Dina to join her mother. It seems the obvious suspect, the royal heir Nicodemus (Jakob Oftebro), can’t be shamed into a confession of guilt. Is he actually innocent? Or is he utterly unashamed of his crimes? Dina soon finds she’s become involved in a deadly political game, and must struggle to free herself and her mother.

What follows is a solid if somewhat conventional adventure story. There are escapes and disguises and secret meetings and dungeons and (yes) dragons. There’s also a refreshing lack of violence; the story doesn’t rely on swordfights to keep moving. Then again, the various incidents and character types do feel familiar: the dissolute but good-hearted heir, the hard-bitten veteran military man with a heart of gold, the absent-minded sage, the corrupt usurper of the throne. If you’re familiar with this kind of story, there won’t be very many surprises.

On the other hand, what it does it does very well. It keeps a good pace, fleshes out characters, and maintains a certain level of credibility — Dina’s adventures and escapes feel real because she’s moving in a world with real consequences and real dangers. The direction brings out a real sense of the physicality of the world: fashions and furniture and books and weapons all feel like used and made objects. They’re things that might have been made by an actual society for day-to-day use, and they unobtrusively anchor the fantasy world of the film in daily life. (I’ll note that the fantasy land of Dunark doesn’t seem particularly ethnically diverse, but also isn’t obtrusively patriarchal; one woman has a professional role as the equivalent of a pharmacist, and while Dina disguises herself as a boy at one point, it’s not to gain any freedom of movement but simply because she needs to disguise herself as something.)

The movie ends on a partial cliffhanger, so while there is a sense of closure to the story, it also cries out for a sequel. Thematically Dina does end the film having changed and grown, and having come to accept her ability in a way she hadn’t at the opening of the story. More broadly, the movie broaches questions of what is right and what is shameful and how people respond to shame and what shame means across a society. I’ve seen people write about the Middle Ages as the point where Western culture generally changed from a ‘shame society’ to a ‘guilt society,’ and there’s perhaps a sense that Dina and her mother represent a kind of older tradition within Dunark, which itself is a very late-medieval setting.

The movie ends on a partial cliffhanger, so while there is a sense of closure to the story, it also cries out for a sequel. Thematically Dina does end the film having changed and grown, and having come to accept her ability in a way she hadn’t at the opening of the story. More broadly, the movie broaches questions of what is right and what is shameful and how people respond to shame and what shame means across a society. I’ve seen people write about the Middle Ages as the point where Western culture generally changed from a ‘shame society’ to a ‘guilt society,’ and there’s perhaps a sense that Dina and her mother represent a kind of older tradition within Dunark, which itself is a very late-medieval setting.

Overall the movie’s a strong addition to the relatively small canon of medieval fantasy films — I think it sits nicely beside movies like Ladyhawke or Dragonslayer (though it’s been a long time since I’ve seen the latter). Apparently Kaaberbøl was first inspired to write fantasy by reading Tolkien, but the movie feels a bit more like a small-scale Game of Thrones without the over-the-top ‘adult’ elements: one might say a corrective, to the TV show at least. The sense is less that of a quest than of political intrigue, and of Dina’s acceptance of her gift as a way to set things to right. Much of the movie is concerned, one way or another, with her using her gifts to prevent or undo injustice, which is apparently the social role of the shamer. So in that sense it’s certainly accurate to think of her as a super-hero — but also as a classic fantasy hero, full stop.

Overall the movie’s a strong addition to the relatively small canon of medieval fantasy films — I think it sits nicely beside movies like Ladyhawke or Dragonslayer (though it’s been a long time since I’ve seen the latter). Apparently Kaaberbøl was first inspired to write fantasy by reading Tolkien, but the movie feels a bit more like a small-scale Game of Thrones without the over-the-top ‘adult’ elements: one might say a corrective, to the TV show at least. The sense is less that of a quest than of political intrigue, and of Dina’s acceptance of her gift as a way to set things to right. Much of the movie is concerned, one way or another, with her using her gifts to prevent or undo injustice, which is apparently the social role of the shamer. So in that sense it’s certainly accurate to think of her as a super-hero — but also as a classic fantasy hero, full stop.

After the film, Kainz returned for a question-and-answer session. Bottenberg asked Kainz how as a veteran director with experience of many genres he approached a high fantasy film. Kainz said that he made up a list of all the fantasy films he could, put up their posters in his workspace, sat down with the movie’s art director, and watched each of them while taking notes. They decided they specifically wanted a feel of grounded fantasy, in which every object in the film felt real and had an obvious function.

After the film, Kainz returned for a question-and-answer session. Bottenberg asked Kainz how as a veteran director with experience of many genres he approached a high fantasy film. Kainz said that he made up a list of all the fantasy films he could, put up their posters in his workspace, sat down with the movie’s art director, and watched each of them while taking notes. They decided they specifically wanted a feel of grounded fantasy, in which every object in the film felt real and had an obvious function.

Asked about the location of the film, Kainz said his Dunark was stitched together from a number of places: cliffs in Ireland, other cliffs in Iceland with a fantastic-looking hole in them, different castles in the Czech Republic, and sets in Prague bought from the TV series Borgia when it wrapped production. Asked what filming in the Czech Republic was like, he said it was complicated — not necessarily because of anything specific to the place, but just due to the process of co-ordinating a Danish crew with Czech workers, and making sure that they were adhering to both Danish and Czech requirements for things such as schooling child actors and stunt girls.

Kainz was asked about a sequel, and he didn’t rule it out. It’ll depend, he said, on how it sells in international territories. Anyone who sees the film and likes it should write about it and review it online.

A question from the audience asked about an element in one of the flashbacks showing a character in a distinctive mask, and Kainz said that it was a piece of artifice: that the mask was a real shaming mask, which technically didn’t belong on the character in that memory, called up by Dina’s shaming powers. The character, said Kainz, wasn’t actually ashamed of that memory, but Kainz had wanted to get the mask into the movie and resorted to what he called a “piece of artifice,” as a result of which he now felt ashamed.

He was asked if all the actors were Danish, and said most of them were except for two Norwegians and one who was Finnish but lived in Sweden (Kainz himself is half-Finnish). He was asked if he’d seen anything else at Fantasia, and he said he’d enjoyed the horror films Cooties, The Hollow, and Slumlord. Someone then asked about the film’s relationship to its source, saying that the ending felt like the end of Book One in a series, which Kainz acknowledged was “spot on.” Kainz said that what inspired him in the adaptation was the main character. He looks for a statement in source material he works with, and found it in the character discovering injustice in her world and bringing justice to others while becoming just herself. Finally, asked if he’d ever thought of trying to make his dragons out of practical effects rather than CGI, he said yes, absolutely, and had had a latex tail made. Ultimately practicalities of budget determined how the dragons were brought onscreen.

He was asked if all the actors were Danish, and said most of them were except for two Norwegians and one who was Finnish but lived in Sweden (Kainz himself is half-Finnish). He was asked if he’d seen anything else at Fantasia, and he said he’d enjoyed the horror films Cooties, The Hollow, and Slumlord. Someone then asked about the film’s relationship to its source, saying that the ending felt like the end of Book One in a series, which Kainz acknowledged was “spot on.” Kainz said that what inspired him in the adaptation was the main character. He looks for a statement in source material he works with, and found it in the character discovering injustice in her world and bringing justice to others while becoming just herself. Finally, asked if he’d ever thought of trying to make his dragons out of practical effects rather than CGI, he said yes, absolutely, and had had a latex tail made. Ultimately practicalities of budget determined how the dragons were brought onscreen.

So that was my Saturday: three movies, all of them high genre pieces, fantasy or science-fiction or both. All in dialogue with past works. Each stood on their own but gained from the comparisons they seemed to invite. In the end all worked as stories and as films. What more can you ask?

(You can find all of this year’s Fantasia Diary posts here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.