Ancient Worlds: The Sabine Women, or How Not to Get Married

As I discussed in my previous two posts, Ovid does some amazing things in writing about sexual assault that I think all authors should take a look at. He often writes about it in a way that is subtle, empathetic, and respectful of rape as a crime with long term impact both on individuals and on larger societal groups.

Notice I said often. Because I want to make it very clear: Ovid was not a feminist. He was not a proto-feminist. He was often times more sensitive to issues that we would consider feminist today, but he was still a product of his time. He advised men when told “no” to keep trying. He advised women being pursued by men that saying “no” was a character defect. And he was willing to, say, turn one of history’s largest abduction scenarios into a punchline.

I refer, of course, to the Rape of the Sabine women, which Ovid covered in the Ars Amatoria. If you have never picked up the Ars, believe me when I say you are missing out. It is at times horrifying for having the sexual politics of, well, a first century wealthy Roman, but it is also an absolutely fascinating glimpse into daily life two thousand years ago. Ovid is advising young men on the art of finding, wooing, and keeping a lover, and he recommends that they take advantage of the close quarters of the theater to meet women. After all, that’s how the first generation of Proper Romans got their wives!

He then launches into the tale of how several dozen young Sabine women were invited with their parents to a performance shortly after the founding of Rome. At a pre-arranged signal, the Romans jumped up, grabbed a girl, and ran for it. The Sabines went back to gather their allies, returned after several months to reclaim their daughters and slaughter Romulus and his skeezy bros, and found that said daughters objected to the Sabines murdering their now-husbands. Peace ensues, and the Romans are left with many years of really awkward family reunions.

Hilarious, right? Not really. Not in the age of Bring Back Our Girls. Not then either, I imagine.

Someone will undoubtedly be tempted to tell me that really, it’s called the Rape of the Sabine Women because “rape” here comes from “rapio” meaning to snatch or seize, and that it’s really about kidnapping, not sexual assault as we would define it. Before you do so, I would counter that a large group of young women were, according to this legend, seized, dragged away from everyone they knew, and compelled into marriage with complete strangers. If that doesn’t meet your definition of rape somewhere along the line, you frighten me.

As you can see at the top of this post and here, painters throughout the Renaissance and beyond didn’t shy away from the intensity of this event. If anything, they’re taking advantage of the opportunity for sensationalism. But Ovid goes for pathos with a hefty dose of humor. Why is that?

It’s partly a question of genre. He’s writing a handbook here, and it’s light and playful. This is a pretty sufficient answer to the first question but it leads directly to the next question: then why tell this story at all? The Ars Amatoria isn’t a classroom assignment. His mistress didn’t tell him “I want a 400 couplet didactic work on my desk by Monday, and it better include the Sabine women.” So we have to assume that he’s playing with his audience here. He’s playing with their expectations of propriety, of proper Roman morality, and of their ideas about their own history. While the Emperor Augustus was in the midst of a massive, decades long Family Values campaign, Ovid is countering that Traditional Roman Values involve getting hard up and grabbing the nearest available female at the show, so who is this Augustus guy to be such a tightass anyway?

And on one hand, you have to love that kind of irreverence. You have to respect someone willing to thumb their nose at absolute power. But as much as I love the poet, I don’t love his means. In order to do that thumbing he’s standing on top of a group of terrified women. Those Sabine girls may have been seven hundred years dead, but their legacy lived on, and we cannot forget that Rome was at that very moment filled with carried-off German, British, Gallic, Israelite and North African women who really wouldn’t have appreciated the joke.

Because that’s the problem with using rape casually in fiction. You are using a very real suffering to make a point, even if in a fictional context. And before anyone says, “That was two thousand years ago!” I would like to offer this:

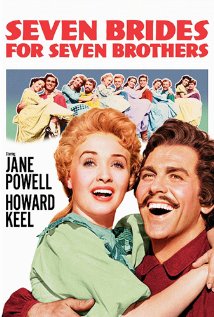

Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, or, The Sobbin’ Women, which was released as a major motion picture in 1954. Same joke, more or less, cleaned up for mass consumption. These tropes are insidious, and it is their very antiquity that makes them such a problem. Their comforting familiarity makes them all that much harder to fight off.

Ovid confronted women’s issues in his time like no other Roman author that we have left. He was capable of an impressive sensitivity and the kind of empathy that great art requires. But he was also capable of throwing that sensitivity under the bus if it furthered another agenda. And that is also something that we all – writers or no – should be wary of.

My mother and two older sisters are big musical fans. So I saw Seven Brides for Seven Brothers a lot. It wasn’t until my late teen that i paid attention to the sobbin women song and what the movie was about.

I remember thinking how awful the sobbin women song is. It’s an upbeat tune and they are singing about stealing women from their homes while they’re crying.

Very interesting read!

I tend to think that this discrepancy between truly understanding the tragedy of rape and also making light of it, and perpetuating rape culture is something that often astonishes me about classical literature. And often less in the literature itself, but in the contemporary commentary about it.

I recently noticed this rereading The Idiot by Dostojewski (I’m sorry for the spelling, I’m using the german version of the russian names here, since I read it in german).

The plot as the author tells it is that Tozkij, some old guy took a little girl, Nastassja Filippovna, in when she was like 10 and when she started to get pretty, some time in her early teens he moved her to a private house with a nanny and came for two months a year to rape her.

At some point she grows up and decides to go to the city to confront him and threaten a scandal, to get him to a) stop, b) give her money. The plot of the book starts from there.

Yet, virtually all commentary I read, writes about these circumstances as if they were themselves from past centuries. They write about Tozkij “seducing” her and randomly set her age to sixteen, though it is never mentioned in the text.

Dostojewski is vague in the beginning that it is hard to realize what has happened, but he quickly becomes very clear. Nastassja jokes about Tozkij “liking” children. She says, she always found him disgusting, she even calls it rape at one point.

What’s more, a lot of her psychological make-up revolves around her horrible past. She keeps only female staff. She is filled with rage at the unjustness of what happened to her, has a ton of trust and also guilt issues, because everybody just treats her as damaged goods (Myshkin being the exception).

The whole thing is front and center really, yet interpretations of the book hardly ever touch it, like I said, they write about “seduction”, when there is really no wriggle room. I wonder why? Is this some misguided attempt to better understand the time?

I mean, in modern works I am fairly fed up with women being motivated by rape, but Nastassja in “the Idiot” is actually an example where it is done really really well. She is at no point one dimensional or simple and Dostojewski is, while he is in no way even remotely feminist, a very very keen observer of people and human nature, in that respect not unlike Ovid.

[…] Gate) Ancient Worlds: The Sabine Women, or How Not to Get Married — “And on one hand, you have to love that kind of irreverence. You have to respect […]