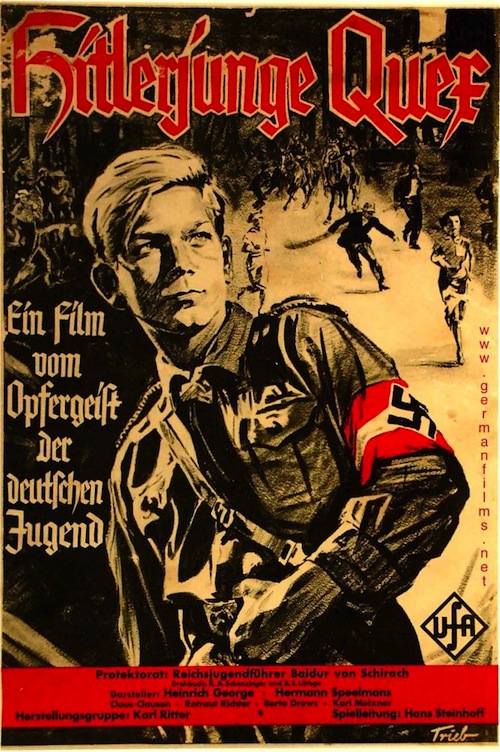

Nazi Film Review: Hitlerjunge Quex

When the Nazi Party took over in 1933, Germany was already a leading nation for film production. From the late 1910s through the early 1930s, its silent films and early talkies were seen all across Europe and were popular in the United States as well. But the year saw a major change in the nation’s film industry as well as its political makeup. Like with every other industry, movie making had to subordinate itself to the goals of National Socialism.

The Nazi party’s first targets were Communists and Socialists, who had fought against them for control of the streets. Many lives were lost on both sides during this era of riots, and one of the more famous of those was a member of the Hitler Youth named Heini Völker, who was killed while distributing Nazi flyers in a Communist neighborhood. There had already been a popular book about the boy published in 1932 titled Hitlerjunge Quex. (“Quex” means “quicksilver”, a nickname Heini got for being such an eager worker). This was turned into a film in the first year Hitler was in power.

This film has been mostly forgotten. The only print with English subtitles I’ve found is here. Most modern discussions of Nazi film center around Leni Riefenstahl and her sullied masterpiece, Triumph of the Will. In contrast, Hitlerjunge Quex is a more personal picture, showing regular Germans struggling in the depths of the Depression during the last days of the crumbling Weimar Republic. Because of its more intimate touch, it is actually a more powerful piece of propaganda.

The film opens with Heini Völker in a tough situation. His father is an unemployed Communist agitator, injured in World War One and unable to keep a job. He drinks and beats Heini’s mother. Heini himself seems to have gotten through this fairly unscathed — he has a job as a printer’s apprentice and he enjoys going to the local fun fair. It’s obvious, however, that he’s looking for a father figure.

And that’s where the Communist Youth Internationale and the Hitler Youth come in. Both want the boy. A comrade of his Communist father pressures Heini to come to some meetings. While the boy is doubtful, being completely innocent of the ideological battles that are tearing his country apart, he enjoys getting friendly attention from a grown man and eventually relents.

The Communist Youth group camps out in the countryside, and are soon partying hard with cigarettes, booze, and loose girls. While most teenaged boys would think they had died and gone to heaven, Heini is a good little Aryan and is uncomfortable with it all. He sneaks off, only to find the Hitler Youth camped out nearby. He’s mesmerized by the uniforms, discipline, and martial music, signs of order and comradeship sadly lacking in his home and, by extension, his country. To his dismay, the Hitler Youth reject him because they recognize him as being part of the Communist group.

Back in the city, Heini can’t get the Hitler Youth out of his mind. Unfortunately, the Communist Youth are still after him. He continues to be associated with them in order to please his father, who is actually showing him some positive attention for a change. Still, he feels the pull of the Hitler Youth, and finds a father figure in a friendly recruiter and friends among some of the teenaged boys and girls.

This is 1930s Germany, and Heini can’t stay in two camps for long. The Communists see him as a security threat, and when he warns his Hitler Youth friends of an impending attack, he has to go. In a scene that had already made the real Heini famous, a Communist street fighter chases him down at a fun fair and stabs him to death. He becomes a martyr for National Socialism, dying with the words, “Our banner flutters before us,” a line from the Hitler Youth anthem. His father, ironically, has already turned to National Socialism as the only answer to his nation’s problems.

It’s a slick piece of propaganda. The Communists are shown to be evil rabblerousers but not without legitimate grievances. Germany was in a terrible state in the 1930s, and even after the Nazis gained power it took some time to fix the economy. This film was part of the war of ideology to show that while Germany had real problems, the solution wasn’t workers’ rights, but national unity. Heini is supposed to symbolize hope for the future, the kind of sacrifice needed to make Germany a great nation again.

To modern eyes, however, the meaning of the film has changed. I came away feeling bad for Heini, both the fictional one and the real one. A young kid desperate to a find a place where he belongs gets used by powerful opposing forces that look at him as a tool, not a child. It happened in 1930s Germany, and it still happens today. And that is where this film’s true value lies.

Sean McLachlan is the author of the historical fantasy novel A Fine Likeness, set in Civil War Missouri, and several other titles, including his action series set in World War One, Trench Raiders. His historical fantasy novella The Quintessence of Absence, was published by Black Gate. Find out more about him on his blog and Amazon author’s page.

There’s an interesting entry about the guy who played in the lead in wiki. There are multiple ironies. Jurgen Ohlsen was supposedly gay and already out of favour with the Nazi party (of whom he was a member) by 1940, when he was sent to a concentration camp. He must have survived as he didn’t die until 1994.

Interesting post. I’ve never heard of this film.

But you claim that “it still happens today.” Really? What examples are you thinking of exactly?

James, whilst it’s not exactly the same, it wasn’t uncommon in east london a few years ago to hear about teenagers and kids being stabbed to death in the streets: so it still happens, albeit as the result of gang violence and drugs as opposed to conflicting political ideologies, but that doesn’t make it any less true.

Intresting review, by the way, sean, really good reading

James,

Child soldiers are used in many parts of the world, and some groups in the Middle East use children as suicide bombers. The specific instance that came to mind when I was writing this post was that 12-year-old boy (about Heini’s age) brainwashed into being an executioner in an ISIS video.

Wasn’t sure what the “it” in “it still happens today” was referring to.

The film, with superb restoration in high definition from an original archival 35mm negative, is available from International Historic Films in Chicago, IL. USA with English subtitles and many bonus materials. My book on the novel and film, HITLER YOUTH QUEX ––A GUIDE FOR THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING READER, is the first book in either English or German wholly dedicated to the novel and film, believe it or not. My book is also available from International Historic Films here: https://ihffilm.com/k100.html . My book has over 400 pages, including 57 B&W and four color plates. One chapter of fifteen pages has more information on the film’s young star, Jürgen Ohlsen, than Wikipedia and all other Third Reich film histories put together — including his never-before reported Wehrmacht duties as a soldier fighting on the Eastern Front for almost four years, his awards with the Iron Cross 2nd Class and then 1st Class, his evacuation to a Vienna Lazarett after being seriously wounded with shrapnel in early 1944, etc, etc,

My book has received a rave review from a very prestigious academic journal:

“Gillespie’s book is a treasure trove for scholars of history, film history and propaganda more generally. This includes graduate and postgraduate students, early career researchers and more established academics. As such it is recommended for the essential classroom reading lists on any course dealing with film propaganda.” – The Historical Journal of Film, Radio & Television (UK/USA), June 2024.

German y’s most important film journal, FILMBLATT, also reviewed the book favourably in its June 2024 issue.