The Tears of Ishtar by Michael Ehart

When my renewed interest in swords and sorcery was sparked a few years ago, one of the first and best books of new writing I found was The Return of the Sword, edited by Jason M. Waltz (reviewed at BG by Ryan Harvey). It’s filled with a passel of great stories and turned me on to several writers I follow closely to this day. Among them are Bill Ward, James Enge, and Bruce Durham. It’s the book that convinced me that there was a renaissance in heroic fiction and that it was worth blogging about.

When my renewed interest in swords and sorcery was sparked a few years ago, one of the first and best books of new writing I found was The Return of the Sword, edited by Jason M. Waltz (reviewed at BG by Ryan Harvey). It’s filled with a passel of great stories and turned me on to several writers I follow closely to this day. Among them are Bill Ward, James Enge, and Bruce Durham. It’s the book that convinced me that there was a renaissance in heroic fiction and that it was worth blogging about.

One of the most intriguing stories, with imagery that’s stayed with me over the years, is “To Destroy All Flesh” by Michael Ehart. I wasn’t surprised to learn it was part of an ongoing series of linked stories. “Flesh” references characters and quests that clearly predate the action at hand.

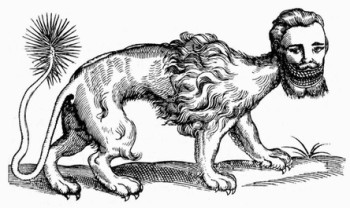

Ehart’s protagonist, Ninshi, a woman from Ugarit in Bronze Age Syria, is enslaved by a flesh-eating demon, the Manthycore. She must provide corpses of warriors for the beast to devour. Her terrible master gave her immortality, great strength, and enhanced healing in order to carry out this task.

By the time I could see again, it had already begun to feed. As always, it started with the soft parts. The belly and the face were its favorites and because it fed so seldom, it showed little restraint. This time it chose to wear the head of a lion, which seemed to be well suited for the task.

It felt the force of my gaze, but did not react right away, engrossed in some particularly savory morsel from the belly of one of the corpses. I took care not to take note of which one. It is a matter of pride that I not look away, but I long ago learned to look without seeing.

She is sustained over the centuries of her servitude by the dream of freeing herself and forcing the Manthycore to restore her lover to life. That quest sets the stage for the tales collected in The Tears of Ishtar.

At the book’s opening, Ninshi has been luring people to their doom for four centuries. There’s a grim, matter-of-factness to the way she hires a pack of bravos in order to kill them. Her acts haven’t escaped people’s attention and songs have been written about her, depicting her as a monster in human form. Her appearance does little to discourage this idea; her body is crisscrossed with scars from countless battles. In some regions she’s known as the Weeping Slayer, their source of terrors that go bump in the night.

With the arrival of a young girl in her life, Ninshi begins to change. The girl, purchased from slave traders, is named Miri. More than the fairly mechanical quest elements of the stories, it is Ninshi’s evolution from heartless murderer to fierce maternal protector that is the best part of The Tears of Ishtar.

While Ninshi’s overwhelming desire to free herself from bondage to the Manthycore never completely goes away, it is assuaged by her relationship with Miri. The girl awakens long-suppressed abilities in the jaded immortal killer to empathize with and sacrifice for others. Ninshi’s gradual emergence from behind the barriers she’s built over the ages is surprisingly emotional and believable. Part of the way Ehart shows this is having Ninshi narrate her own tale before the arrival of Miri, narrowly focusing on her version of events. After that, the stories switch to the third person, pulling back to give the reader a view of two characters as they grow closer together.

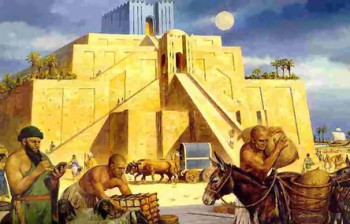

For folks like me, bored of the default North European settings of too much fantasy, Ehart’s choice of the ancient Near East is a great one. It’s a land already littered with ruins of lost civilizations. Even languages have risen and fallen out of use. Deities and demons wander the landscape, usually leaving death in their wake.

The world is old enough that cities have been built atop already forgotten earlier ones. The mighty city-state of Nineveh is several thousand years old by the 13th century BC time of The Tears of Ishatar.

The world is old enough that cities have been built atop already forgotten earlier ones. The mighty city-state of Nineveh is several thousand years old by the 13th century BC time of The Tears of Ishatar.

Miri slid across the narrow street, concealed by the shadows. Nineveh was huge and she was lost. To her left she could hear the river Khosr which ran through the city. They had not crossed it, so she must be still in the northern quarter, but the streets were so twisted and overhung by buildings that she had no idea where she had gotten to. She had eluded pursuit, but in the dark and unfamiliar alleys and passages, she stood little chance of finding the Nergal Gate through which they had entered that morning.

Ninshi’s world is also much less politically organized than many standard fantasy ones. The only empires mentioned are those of the Hittites and Egyptians, and then only offstage. The action of the stories is confined to regions of city-states, villages, and wilderness caravanserais. Between one city and the next lies only desert, where thirst and sandstorms are as likely to kill you as the endemic bandits.

There’s plenty of action and mayhem in the book, but where it excels is at creating memorable scenes and images. Partly, Ehart does this by drawing from the beliefs and history of the region. In one section, Ninshi and Miri must hunt down a pack of bandits said to be living in the ruins of something called the Great Vessel.

From the small hill, they could see down into the trough-shaped valley. Early snow coated its hillsides. Thin lines of smoke rose into the chill air from the far end, where Miri could make out the faded colors of tents pitched in the shelter of a large black object that protruded from the icy wall of the mountain. For the squared-off bulky shape to be so clear from so far, it had to be enormous.

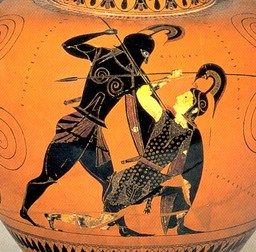

Later the pair meet a party of Amazons. Not just a band of warriors out for adventure or hire, they are seeking the tomb of their queen who years ago went into the West to fight in a great war along the shores of the Middle Sea. It would be a melancholy tale on its own, but it gains in resonance from its link to the tragedy of the Trojan War.

Later the pair meet a party of Amazons. Not just a band of warriors out for adventure or hire, they are seeking the tomb of their queen who years ago went into the West to fight in a great war along the shores of the Middle Sea. It would be a melancholy tale on its own, but it gains in resonance from its link to the tragedy of the Trojan War.

I don’t know nearly enough about the region and period to say if Ehart gets it right, but it feels right. In his hands it’s a world, awash with myths and legends, that makes a perfect setting for his undying heroine.

I read one review that dismissed The Tears of Ishtar as simply old school swords and sorcery with a by-the-numbers quest driving the action. Yeah, I gotta disagree on that. The S&S may indeed be old-school, but it’s pretty terrific stuff. Ehart does a good job with the action scenes, never making Ninshi feel too unbelievable or indestructible. The quest aspect — find some magic jewels for a big boss so she can get free — is pretty generic, but it’s only the engine to get the characters moving. The encounters along the path and her years with Miri rehumanize Ninshi, and that is far more interesting and important than any quest.

This is one of the many, many good books that fell down a hole and appears to be forgotten. It doesn’t seem to have garnered many reviews and it looks like Michael Ehart has moved on from writing. If that’s true then it’s a shame, because with The Tears of Ishtar he created something different from the run-of-the-mill fantasy fiction.

In case anyone reading this review gets a sense of deja vu, that’s understandable. Bill Ward reviewed The Tears of Ishtar for Black Gate back in 2012.

Great review Fletcher, I’m very glad you read this book. It would be a shame if Michael has moved on, he is a clever and thorough writer.

Once again, thank you for all the reading and reviewing you do!

Great, fascinating review. Sadly, Amazon appears to be out of the book, and there’s no ebooks out that I can tell…

Just got the anthology on Amazon, though (that is, the ebook) – sounds interesting!

Thank you Fletcher, for your kind words. Personal issues have kept me from the keyboard, but I hope to return soon.

@Jason – Thanx, as always, for the support and kind words!

@hessian – it’s available used at reasonable prices

@Aonghus – Cool! You will not be disappointed.

@Michael – You’re welcome. Thanx for a very enjoyable read. Best wishes on getting back to writing at some point. The real world always trumps our fictional ones.

[…] normally ambivalent about fix-up novels. I’ve read good ones (see Tears of Ishtar by Michael Ehart for a great example), but in general I feel they end up too fragmented to be read […]