Through the Woods and Other Stories by Emily Carroll

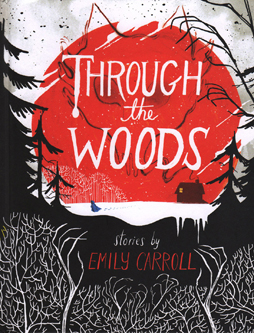

And now for some utterly uncontroversial awards news: on April 22, the nominees for the 2015 Eisner Awards were announced. You can find the complete list here, representing some very impressive work. I’ve written in the past about Astro City, Sandman: Overture, and Saga; I want to take a moment now to write a bit about one of the other nominees. Emily Carroll’s up for two Eisners, ‘Best Graphic Album — Reprint’ for her anthology Through The Woods, and ‘Best Short Story’ for her online piece “When the Darkness Presses.” They’re both excellent.

And now for some utterly uncontroversial awards news: on April 22, the nominees for the 2015 Eisner Awards were announced. You can find the complete list here, representing some very impressive work. I’ve written in the past about Astro City, Sandman: Overture, and Saga; I want to take a moment now to write a bit about one of the other nominees. Emily Carroll’s up for two Eisners, ‘Best Graphic Album — Reprint’ for her anthology Through The Woods, and ‘Best Short Story’ for her online piece “When the Darkness Presses.” They’re both excellent.

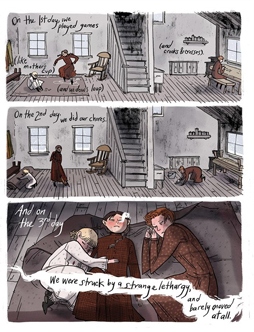

I first stumbled across Carroll’s comics shortly before the Eisner nominations were made public. I found a copy of Through The Woods at my local library, after which I read through the short stories on Carroll’s web site. I thought both the print and online works were brilliant comics. Mostly horror or dark fantasy with a strong mythic edge, they experiment with form in order to get at the heart of their narratives. Panel designs and lettering and storytelling are all unobtrusively intelligent and quietly inventive, finding new ways to bring out the emotional textures of the tales.

Carroll changes her style and approach with each story, but maintains a distinctive voice. She moves easily from web to print, working with the possibilities of page design in both mediums in a way that feels not just accomplished but effortless. Reading through her work you’re struck by the range of approaches but also by the sense of an overall unity — the unity that emerges from a major artist exploring the themes that hold meaning for her.

A bit of background: Carroll studied animation at school, and began drawing webcomics in the spring of 2010. She created several short stories that year, and one that she put up on Halloween, “His Face All Red,” became something of a sensation after being recommended by Neil Gaiman on Twitter. In mid-2011 Carroll won the Joe Shuster Award for Outstanding Web Comics Creator; the Shusters recognise achievement by Canadian comics creators, and Carroll would win the award for her webcomics again in 2012.

A bit of background: Carroll studied animation at school, and began drawing webcomics in the spring of 2010. She created several short stories that year, and one that she put up on Halloween, “His Face All Red,” became something of a sensation after being recommended by Neil Gaiman on Twitter. In mid-2011 Carroll won the Joe Shuster Award for Outstanding Web Comics Creator; the Shusters recognise achievement by Canadian comics creators, and Carroll would win the award for her webcomics again in 2012.

Carroll’s kept on posting short stories to her website in the years since, and one of her pieces from 2014 is now nominated for an Eisner. Through the Woods was also nominated for the ‘Best Graphic Album — Reprint’ Eisner, although only one of the book’s five stories is a reprint, “His Face All Red.” At any rate, Through the Woods has won praise from a number of quarters already, and richly deserves it. It’s a good representation of Carroll’s work, mixing atmospheres from fairy tales and horror fiction to unsettling effect. Carroll’s technique is elegant but also invisible, drawing you into the stories and sweeping you breathlessly along through mounting tension, spare yet evocative writing, and the profound unsettling horror of what lies just out of sight. It’s one of the rare books that really is suitable for all ages; there’s an adult awareness of death and emotional texture for those who look for them, but those things don’t get in the way of a dreamlike and often archetypal feel.

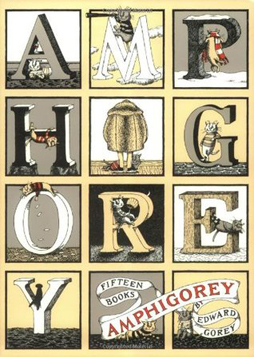

That comes in part from Carroll’s drawing style, which seems to mix Kate Beaton and Edward Gorey, but mostly from her sense of storytelling, which is note-perfect. She always knows what to show and what to imply, and frames her images precisely to create compositionally strong and narratively intriguing pictures. Her sense of panel shape and page layout is excellent, moving the reader’s eye where she wants at the speed she wants, and doing so with grace and apparent ease. In print, splash pages are used for silent, haunting moments, punctuating visual rhythms which flow in perfect harmony with her prose.

That comes in part from Carroll’s drawing style, which seems to mix Kate Beaton and Edward Gorey, but mostly from her sense of storytelling, which is note-perfect. She always knows what to show and what to imply, and frames her images precisely to create compositionally strong and narratively intriguing pictures. Her sense of panel shape and page layout is excellent, moving the reader’s eye where she wants at the speed she wants, and doing so with grace and apparent ease. In print, splash pages are used for silent, haunting moments, punctuating visual rhythms which flow in perfect harmony with her prose.

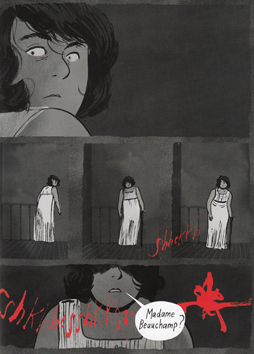

Words, in or out of balloons, become design elements. Text is large, handwritten, and seems wilder than it actually is. The lettering’s supremely expressive, recalling the experimentation of Dave Sim. Carroll changes the size, colour, and type-style of words for emphasis, and rather than use traditional captions she weaves narrative text through her panels to help tie her pages together. It’s a highly distinctive integration of images and text, which both seem to have the shape of sentences: perfectly-formed clauses and panels build sequences of meaning.

Above all, Carroll’s sense of colour is stunning. She creates shocking contrasts of bright reds and blues against dark backgrounds, but also understated compositions with much subtler colours, especially in her online comics. More than just visually striking, though, Carroll makes her colour sense work narratively. Strong emotions are evoked with sudden and surprising choices, but colour also emphasises words and images, and subtly links characters and ideas. You can see this in Through the Woods when a retelling of the Bluebeard fable uses an electric blue as a motif representing the sinister husband, or when the short-short stories that introduce and conclude the book are tied together by a green bedspread.

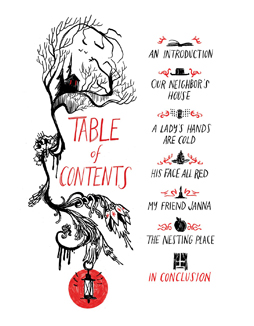

Through the Woods follows a three-page introduction about reading and monsters under the bed with “Our Neighbour’s House,” a story set (it seems) in the century before last. It’s a tale of three girls who live deep in the woods, and of their father’s vanishing, and of what they must do as danger seems to close in all around them. “A Lady’s Hands Are Cold” is the retelling of the Bluebeard story, seemingly set around two hundred years ago; like the first story it’s paced spectacularly, building an atmosphere of unease that builds to pure horror and a cathartic final attempt to escape.

Through the Woods follows a three-page introduction about reading and monsters under the bed with “Our Neighbour’s House,” a story set (it seems) in the century before last. It’s a tale of three girls who live deep in the woods, and of their father’s vanishing, and of what they must do as danger seems to close in all around them. “A Lady’s Hands Are Cold” is the retelling of the Bluebeard story, seemingly set around two hundred years ago; like the first story it’s paced spectacularly, building an atmosphere of unease that builds to pure horror and a cathartic final attempt to escape.

“His Face All Red” is next, the story of a villager who sees his brother return from a forest where he supposedly faced a monster. Except the brother is dead, as the villager knows but cannot say. The adaptation of the original web story for print is surprisingly smooth. Small silent panels are blown up or dropped to keep the pacing and page breaks coherent, while lettering is occasionally redone to take advantage of a different page layout. One silent sequence, in which a character makes a decision, is significantly changed in its pacing. I think that overall I slightly prefer the original, which makes use of the ‘infinite canvas’ of the web to present more vertical sequences of panels, and where, as in many of Carroll’s webcomics, ‘next’ prompts pull the reader in by requiring small interactions.

“My Friend Janna” is another story from the nineteenth century, following two young girls who present themselves as spiritualists — one claims to speak with the dead during séances, while the other hides in the walls and makes the eerie knocking sounds of the supposed ghosts. But then a real spirit enters the picture, and the story grows darker. As with a number of Carroll’s stories, the main tale is clear enough but the implications and allusions seem to broaden and deepen the picture, hinting at more detail without necessarily explaining anything, without softening the dread of the fundamentally unknowable. “The Nesting Place” is the longest story in the book, and in some ways the most complex; it’s one of the few that presents a recognisable society, though most of it takes place at a country house where a schoolgirl makes a horrifying discovery about her brother’s fiancée. It’s got the most overtly horrific imagery in the book, but that imagery’s well-earned, and however grotesque the tale becomes, the deft pacing and story-within-the-story structure seem to imply that there’s always more and worse lurking just out of sight.

“My Friend Janna” is another story from the nineteenth century, following two young girls who present themselves as spiritualists — one claims to speak with the dead during séances, while the other hides in the walls and makes the eerie knocking sounds of the supposed ghosts. But then a real spirit enters the picture, and the story grows darker. As with a number of Carroll’s stories, the main tale is clear enough but the implications and allusions seem to broaden and deepen the picture, hinting at more detail without necessarily explaining anything, without softening the dread of the fundamentally unknowable. “The Nesting Place” is the longest story in the book, and in some ways the most complex; it’s one of the few that presents a recognisable society, though most of it takes place at a country house where a schoolgirl makes a horrifying discovery about her brother’s fiancée. It’s got the most overtly horrific imagery in the book, but that imagery’s well-earned, and however grotesque the tale becomes, the deft pacing and story-within-the-story structure seem to imply that there’s always more and worse lurking just out of sight.

The visually-spectacular conclusion to the book presents a version of (or perhaps prequel to) “Little Red Riding Hood.” It echoes the introduction’s brief meditation on storytelling. Reading a story’s like taking a walk in wolf-haunted woods: maybe you get where you’re going safely, but what happens next time? Carroll’s stories raise the question more than most do. They invite rereading, and even meditation. Each alone is rich and strange. As a whole, Through the Woods offers glimpses into unknowable abysses, into bottomless pits in the woods and spaces between walls and dark caves in which brooding monsters lurk.

You can read through Carroll’s online work in chronological order, starting with the fairy-tale retelling “The Hare’s Bride.” Already in that piece Carroll’s sense of colour and pacing are obvious, and as you go on you see the stories becoming structurally more complex. They increasingly take advantage of the nature of the web, with well-placed links and mouse-over text. “The 3 Snake Leaves” is a choose-your-own-protagonist adventure, which tells the same story two different ways. “Grave of the Lizard Queen” and “Margot’s Room” both start with one image which contains links to fragments of an overall tale, encouraging the reader to piece events together. “All Along the Wall” is a prequel to “The Nesting Place” that frames a bright, colourful horror short with a shadowy black-and-white Christmas frame.

You can read through Carroll’s online work in chronological order, starting with the fairy-tale retelling “The Hare’s Bride.” Already in that piece Carroll’s sense of colour and pacing are obvious, and as you go on you see the stories becoming structurally more complex. They increasingly take advantage of the nature of the web, with well-placed links and mouse-over text. “The 3 Snake Leaves” is a choose-your-own-protagonist adventure, which tells the same story two different ways. “Grave of the Lizard Queen” and “Margot’s Room” both start with one image which contains links to fragments of an overall tale, encouraging the reader to piece events together. “All Along the Wall” is a prequel to “The Nesting Place” that frames a bright, colourful horror short with a shadowy black-and-white Christmas frame.

“When the Darkness Presses” is a good example of Carroll’s more recent work. It does something I don’t think I’ve ever seen in a webcomic, framing ‘everyday’ panel sequences with false banner ads (which may or may not thematically refer to the main story), then cutting to long vertical sequences of panels against a black background to emphasise the strangeness or uncanniness of specific sequences. And then as the comic goes on the false ads change to show the unreal erupting into the real — beyond the ‘real’ of the story, in fact, to the ‘real’ that frames the story. It’s a nice trick.

The main outline of the story’s simple. A girl is house-sitting for a family. A friend stays with her overnight. They talk about dreams, and about the first girl’s boyfriend. The first girl grows suspicious of the second, and alienates her; we see the first girl growing more and more isolated from the world around her, locked away in the house, pulled ever-deeper into her nightmares. By the end reality and dream have blurred into each other.

The main outline of the story’s simple. A girl is house-sitting for a family. A friend stays with her overnight. They talk about dreams, and about the first girl’s boyfriend. The first girl grows suspicious of the second, and alienates her; we see the first girl growing more and more isolated from the world around her, locked away in the house, pulled ever-deeper into her nightmares. By the end reality and dream have blurred into each other.

The trick, of course, is in the telling. The playing-about with false banner ads is an example of the way Carroll experiments with the narrative. Doorways and doors are key to the dream, and turn up in the waking world as well. Images sewn into a magenta-coloured bedspread recur. Vertical dream-narratives give way at a climactic point to a horizontal sequence which creates a surprisingly different reading experience. It’s all stunningly effective.

Reading over Carroll’s stories you might think of Neil Gaiman in the way Carroll evokes dream and myth. Her dialogue’s as rhythmic, but more realistic, and her fiction is overall less mannered. Personally I’m reminded a lot of Kelly Link in the strangeness of the structure of the stories and the way certain things are left unsaid. At the same time, I find Carroll’s work richer — I find the spareness of Link’s work rarely engages the senses, while the lush colours Carroll uses along with her illustrative style together imply smells and textures. I’d also been thinking that Carroll’s work recalled Angela Carter’s short stories until I read this interview, in which Carroll mentions having come to Carter’s fiction only recently. The tones and approaches do seem similar, and Carter’s stylistic richness seems at least occasionally close to what Carroll does in her comics.

Reading over Carroll’s stories you might think of Neil Gaiman in the way Carroll evokes dream and myth. Her dialogue’s as rhythmic, but more realistic, and her fiction is overall less mannered. Personally I’m reminded a lot of Kelly Link in the strangeness of the structure of the stories and the way certain things are left unsaid. At the same time, I find Carroll’s work richer — I find the spareness of Link’s work rarely engages the senses, while the lush colours Carroll uses along with her illustrative style together imply smells and textures. I’d also been thinking that Carroll’s work recalled Angela Carter’s short stories until I read this interview, in which Carroll mentions having come to Carter’s fiction only recently. The tones and approaches do seem similar, and Carter’s stylistic richness seems at least occasionally close to what Carroll does in her comics.

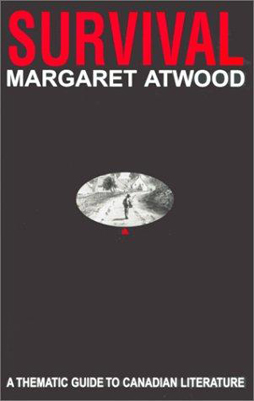

In the same interview, Carroll mentions that she’s been setting more of her stories in Canada recently, and specifically refers to Margaret Atwood’s 1972 study of Canadian literature Survival as identifying certain themes that resonate with her. Atwood suggested that Canadian literature was less interested in happy endings than in simple survival — that it tended to the macabre and downbeat, but not to grand tragedy. She further suggested that the central characters of Canadian writing were victims, who assumed certain ‘victim positions’ of varying levels of usefulness; that’s something that seems to have obvious bearing on characters in horror stories.

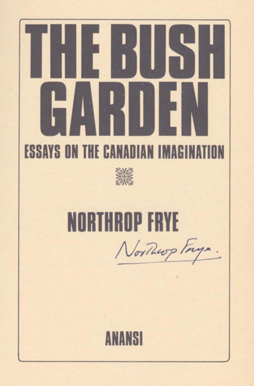

Atwood, like Northrop Frye, also discussed the garrison mentality of much English-Canadian writing: stories that contrast a stolid and civilised centre with a forbidding wilderness. But which might also hint at something attractive in the wilderness, a kind of wisdom beyond the safety of the garrison, a wisdom that implictly opposes and undermines the garrison. The wild is frequently dominant, the garrison beleaguered if not actively delusional; the uncontrollable and the external have the upper hand, and may deform the rational and orderly.

Atwood, like Northrop Frye, also discussed the garrison mentality of much English-Canadian writing: stories that contrast a stolid and civilised centre with a forbidding wilderness. But which might also hint at something attractive in the wilderness, a kind of wisdom beyond the safety of the garrison, a wisdom that implictly opposes and undermines the garrison. The wild is frequently dominant, the garrison beleaguered if not actively delusional; the uncontrollable and the external have the upper hand, and may deform the rational and orderly.

All this fits well with Carroll’s work. She implies that many of the stories in Through the Woods are set in Canada (though none of them explicitly say so), and you can see these themes at work through the book. Survival is perhaps more at issue than in most of the literature Atwood examines, but Carroll’s stories are full of isolated comunities and homes, and of wild dark woods with supernatural powers. And many of these fictions are about the contrast between the artificial boundaries of a house, a garrison, and the horror lurking without which also gains a foothold within. You could argue that Carroll takes traditional Canadian themes and shows how perfectly they fit the form of the horror story. (According to her bio, Carroll lives with her wife in Stratford, Ontario, the territory of the Southern Ontario Gothic of Atwood and Robertson Davies.)

Most of Carroll’s stories are set in the past, in traditional and usually patriarchal societies, but usually feature a young female lead. Certainly it’s possible to see a lot of her fiction as having to do with young women trying to negotiate places for themselves. There’s something poignant about Yvonne, the noisemaker in “My Friend Janna,” hiding invisibly in the walls (and it’s notable that historically many prominent spiritualists were women, while the trickery of Janna and Yvonne specifically recalls the fraudulence of the Fox sisters). The horror of “The Nesting Place” moves from generation to generation of women, always concerned with its children and always unseen by the lone male of the story. Elements of “Our Neighbour’s House” recall the metaphors underlying motifs from “Little Red Riding Hood” on one hand and Dracula on the other; while “A Lady’s Hands Are Cold” plays with the deeply gendered Bluebeard fable. And the first story of the book, “Our Neighbour’s House,” is set in motion by the absence and presumed death of the father of three girls, who then must work out what to do in his absence.

There’s nothing stated overtly about these themes (although one does notice the monster in “The Nesting Place” telling the heroine that she’ll be liked more “once my babies stretch you into something tall, slim, and pretty”). But much of the effect of Carroll’s work comes from her ability to evoke the things she does not choose to directly depict. It’s a useful power for a horror writer to have: the ability to imply what is to be most deeply felt. It’s particularly important in a visual medium to be able to convincingly refrain from showing things. Carroll’s often-unsettling choice of framing — panels focussing on parts of faces, on teeth or eyes — helps build up to climaxes where the key moments are left to the reader’s imagination.

There’s nothing stated overtly about these themes (although one does notice the monster in “The Nesting Place” telling the heroine that she’ll be liked more “once my babies stretch you into something tall, slim, and pretty”). But much of the effect of Carroll’s work comes from her ability to evoke the things she does not choose to directly depict. It’s a useful power for a horror writer to have: the ability to imply what is to be most deeply felt. It’s particularly important in a visual medium to be able to convincingly refrain from showing things. Carroll’s often-unsettling choice of framing — panels focussing on parts of faces, on teeth or eyes — helps build up to climaxes where the key moments are left to the reader’s imagination.

Read through Carroll’s work and you see that she keeps finding new and more complex ways to tell her tales. There’s a formal restlessness, a constant experimentation, in her work. She has a very distinctive style, and a certain emotional terrain, but always puts things together in a new way. Her stories are brilliant horror fiction, and great comics. I’m happy she got the Eisner nominations this year, and I expect she’ll get many more in future.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.