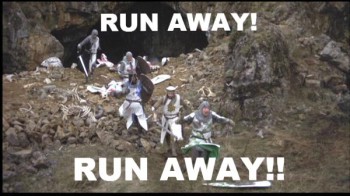

The Art Of Retreat, a.k.a. “Run Away, Run Away!”

Over the last thirty-five years, I’ve enjoyed gaming (mostly D&D and its ilk) with something like ten different role-playing groups. Other than the blindingly obvious traits that all such gatherings share, such as a love of good company or having a pulse, the most salient characteristic exhibited by each band of gamers was a stunning inability to retreat in the face of bad situations or superior foes.

Over the last thirty-five years, I’ve enjoyed gaming (mostly D&D and its ilk) with something like ten different role-playing groups. Other than the blindingly obvious traits that all such gatherings share, such as a love of good company or having a pulse, the most salient characteristic exhibited by each band of gamers was a stunning inability to retreat in the face of bad situations or superior foes.

I find this mind-boggling. Fascinating, too.

Let me provide a couple of classic examples. Once upon a time, my friends Nick and Suzanne, playing a barbarian and a cleric, respectively, “went on ahead” of the rest of the group, which is to say, the rest of us couldn’t make it that week. They came upon a lonely cave inhabited by creatures we later came to call graylocks. I don’t recall the source or where the referee culled them, but that doesn’t matter: they were mean and tough. Think ogres with spells.

Nick and Suzanne pressed the fight, even though they were outnumbered; they pressed the fight even though their opponents were winning; they pressed the fight even when it was hopeless. In short, they behaved as if they could not possibly lose. It took hours of painstaking work over the ensuing weeks to rescue them.

A year or so later, in a campaign that borrowed heavily from Greyhawk, the referee decided it would be fun to attack our party with a minor deity, a real piece of work (and evil, too!) called Iuz. Nasty old Iuz teleported in, launched a fearsome assault, and did some terrific damage. Then he blipped out again, ‘cos hey, he was just dropping in for kicks and evil gods can do that sort of thing. Well, we were pretty steamed, and we had some sort of magical doo-hickey that allowed us to follow anyone who teleported away, so what did we do? We followed. We took the fight right to Iuz’s doorstep — or whatever demonic sludge he employed that served as a doorstep. True, we did catch the referee by surprise, but while we got a few good licks in, we should not have done that. We got our tails whipped, and we had no exit plan. Even when it was time to retreat, we kept battling away, and as a result, we very nearly got wiped off the map.

A final example: a few years ago, I had the pleasure of taking the ref’s reins with a crew of gamers that included BG’s very own Howard Andrew Jones, he who knows the uses of The Bones Of the Old Ones and other Great Magicks. I set up an ambush using a group of bounty hunters who’d come to haul one of the Jones Gang off to prison. I didn’t make the bounty hunters overpowering, but I did make sure they had the advantage of surprise and the better position. I assumed Howard and Co. would retreat. They did no such thing. As with the two previous examples, they pressed the fight, they charged ahead, and they did not stop to reconnoiter or regroup. For their troubles, they very nearly got slaughtered.

A final example: a few years ago, I had the pleasure of taking the ref’s reins with a crew of gamers that included BG’s very own Howard Andrew Jones, he who knows the uses of The Bones Of the Old Ones and other Great Magicks. I set up an ambush using a group of bounty hunters who’d come to haul one of the Jones Gang off to prison. I didn’t make the bounty hunters overpowering, but I did make sure they had the advantage of surprise and the better position. I assumed Howard and Co. would retreat. They did no such thing. As with the two previous examples, they pressed the fight, they charged ahead, and they did not stop to reconnoiter or regroup. For their troubles, they very nearly got slaughtered.

In short, they employed as axiomatic the immortal if unsubtle words of Bruce Springsteen: “No retreat, no surrender.”

So what is it that makes people (or at least gamers) so reckless?

Is it simply that the stakes are low? That we’re dealing with characters made of graphite and cheap paper — or, now, binary code? I can’t quite believe that, because my own pulse never fails to race when my character is in combat, or in any form of danger. I role-play in mortal fear that my avatar, alter-ego, or whatever you wish to call him, her, or it will die.

And yet, as with example number two, above, I, too, have succumbed to the will of the group.

Therein, I think, lies the key. In a group, especially a group that enjoys its own company, the members egg each other on. They believe in the bromide of safety in numbers. They trust that their buddies will have their back.

Therein, I think, lies the key. In a group, especially a group that enjoys its own company, the members egg each other on. They believe in the bromide of safety in numbers. They trust that their buddies will have their back.

Result? “Damn the torpedoes, and full speed ahead!”

(My apologies: I was hoping to make this an all-Springsteen post, but somehow Admiral Farragut has elbowed his way in. Ah, well. If the shoe fits.)

I’d also suggest that a significant contributing factor is the design structure of D&D and similar games. Characters “progress,” they rise with experience; they gain power, prestige, and prowess. As a result, they have a track record behind them that’s necessarily rosy: they didn’t get where they are now by losing. After a while, success becomes expected. It takes a pretty severe shock to derail that sort of thinking.

Outright denial comes into play, most certainly, and here I mean at a human rather than at a systemic (gaming) level. Our innate failure to imagine our own demise affects our game strategies. The default existential position of “I’m living and breathing now, therefore this will forever be the case” applies to made-up characters as well as to our real and mortal selves. Thus fools rush in where angels fear to tread. (Thank you, Alexander Pope.)

Finally, there’s the difficulty, for even the most experienced, creative, and harsh referees, of posing a suitable challenge to large groups of clever, quick-thinking players. Shy of intentionally creating a meat-grinder scenario (think Gygax’s Tomb Of Horrors module, discussed ELSEWHERE on this site), referees will always be outnumbered; it’s one mind against the hive mind and the teamwork of the group. Again, the players become accustomed to success. On the day when they finally do meet an insurmountable challenge, it might take them a while to recognize (dare I say it) the reality of their situation.

Finally, there’s the difficulty, for even the most experienced, creative, and harsh referees, of posing a suitable challenge to large groups of clever, quick-thinking players. Shy of intentionally creating a meat-grinder scenario (think Gygax’s Tomb Of Horrors module, discussed ELSEWHERE on this site), referees will always be outnumbered; it’s one mind against the hive mind and the teamwork of the group. Again, the players become accustomed to success. On the day when they finally do meet an insurmountable challenge, it might take them a while to recognize (dare I say it) the reality of their situation.

I haven’t done any gaming for about two years now, but I’ll be dipping my toes in the water again in July, and I wonder: given my hard-won expertise, my interest in this problem, and the wisdom of my many (ugh) years, will I be able to spot a hopeless, disastrous situation if it arises? Will I be able to respond in a sensible manner before it engulfs our party?

Nah.

Full speed ahead, say I! No surrender, and damn the fearful treading angels!

‘Til next time.

Onward.

Mark Rigney has published three stories in the Black Gate Online Fiction library: ”The Trade,” “The Find,” and “The Keystone.” Tangent called the tales “Reminiscent of the old sword & sorcery classics… once I started reading, I couldn’t stop. I highly recommend the complete trilogy.” In other work, Rigney is the author of “The Skates,” and its haunted sequels, “Sleeping Bear,” and Check-Out Time. His website is markrigney.net.

I too have been privy to more than one TPK (total party kill), both as a player and as a DM/ref. That being said though, I’ve also seen (though rarely) a few good retreats in my day, especially if the player has a prized character and the DM/ref as a reputation for letting the dice fall where they may.

I was part of a DnD Encounters (i.e. 4th edition) group at a local game shop a couple of years ago playing a minotaur barbarian. I have to admit that I felt rather impervious in that guise and would often storm imprudently any just about any mess. Needless to say, Mr. Moomoo died not long into that campaign.

It was worth my writing this post just to discover a character named Mr. Moomoo.

LO bloody L!

: )

Mark

D&D is indeed at fault. But only since 3rd Edition. The blame lies not so much in the rules changes the edition brought, but in the presentation. Published adventures in particular. There are lots of adventures in which the players have to fight and defeat this monster in this room, because there are no other possible paths to take and the monster will attack them on sight- And unless they defeat this monster in battle, the game can not continue. Either they fight and defeat it, or the adventure stops right there. The Dungeon Masters Guide doesn’t say a single word to tell GMs to not do this either.

In the older editions it was almost always assumed that you could take another route to your goal and there might be ways to get past many of the creatures without fighting them. And not fighting them also was a good idea, because way back, you did not get XP for fighting monsters, but XP for carrying treasure back to town.

For the last 15 years, retreat or avoiding combat in D&D and Pathfinder simply is not an option, as far as the official material is concerned.

The only times I’ve seen retreat become somewhat of a norm in an RPG is with the old SPI Dragonquest game, at least for the 2 different groups with which I played. Pushing ahead was still more common, but withdrawal from combat was a common possibility. My thinking here is that it had to do with the game’s mechanics. Unlike D&D, as example, in DQ a high-level character could be taken out by a lower level character, and relatively easily (1 or 2 good dice rolls and your longtime character was toast), and those low level characters didn’t necessarily drop after being hit once or twice. It’s just a different way of playing.

Concerning Martin’s comments about “older editions,” we must be remembering different things about the Gygax DMG I first read those decades ago. The game was practically set up for dungeon crawling, which meant going into a room, killing a monster, and rushing off with treasure, and honestly, I don’t remember a lot of options to “take another route.” In my opinion, it’s all in how you play, not the system.

@mark

The minotaur I played after Moomoo was a cleric/fighter we jokingly called Moo-hatma Gandhi!

@Ty

Call of Cthulhu is one RPG where retreat, and similar actions, are fairly common. You’ll blow through characters left and right if you try to muscle your way through even simple encounters with human cultists, much less monsters.

I recall being forced through the Shrine of Tamoachan (spelling?) module and being totally unable to get past a cave where we were supposed to hold our breath and swim through some sort of underwater passage while being assaulted by beasties of some type. The module assumes the entire party has been buried underground by an unstable landslide; there is no other option to proceed except through that cave.

Well. We weren’t the right group at all for that job: wrong spells, wrong class, levels too low. Result: we “died.” The players then rebelled, accused the DM of setting us up to fail, and went off to play with people more on our wavelength––with our characters magically alive, since that adventure simply never happened.

Germane to this thread? Hope so. Thanks, all, for reading.

Yeah, that would be one of those tournament modules, markrignev. Those were meant to be played at a convention with single-use premade characters with limited playtime.

I really have no idea what they where thinking later reprinting these and releasing them alongside regular adventure modules. Because such stories seem to have happened all the time with GMs who didn’t know that you can’t just drop them into a regular campaign. Same with the Tomb of Horrors and the Lost Caverns, and pretty much all the infamous Killer-Modules.

The best GM I ever had ran our party into a tough fortress we probably could have taken with only one or two fatalities in our party of 16 players with an entourage of 4 or 5 loyal NPCs. After our first run-in with the fortress’s defenders, we sat around like dopes for about 20 minutes of in-game time first-aiding and healing each other. So the second wave of defenders descended on us, and half the party died. A quarter of the party escaped together. Three were able to escape by magic, but not to control where in the multiverse they went. Only one of those characters came back, the price being that his trickster God turned him into a woman.

My character, the stealth pro, missed the escape lifeboat and had no magic, so she spent the next ten years of her life hiding inside the fortress before she got her chance to escape.

Sarah – That’s hilarious. And a perfect example of what first got me thinking about all this. Ten years marooned! Was the castle named Calypso? (Which spellcheck will not let me spell with a K. Humph.)

Martin – I would assume that “killer modules” were released because players unable to attend gaming conventions wanted their shot at the action. And they proved, with their wallets, that TSR was justified in making that possible. I know I bought Tomb of Horrors with my very own allowance money, way back when…it sure was more fun to referee than to play…