A World without Tolkien

I like to commemorate the birthdays of authors whose works I’ve enjoyed or that have exercised an influence over me in some way. Unfortunately, I only write one day a week here at Black Gate. Consequently, the odds that an anniversary of one of the handful of writers I hold in high esteem should fall on a Tuesday aren’t high enough that I can consistently write commemoration posts on the day in question. Sometimes, like last week’s post about Fritz Leiber (which proved surprisingly popular, if the comments it generated are any indication – thank you), the calendar cooperates somewhat and my post can appear a day before or a day after the intended date. It’s a bit of a cheat, but not one so egregious that my over-developed sense of propriety feels it’s “wrong.”

I like to commemorate the birthdays of authors whose works I’ve enjoyed or that have exercised an influence over me in some way. Unfortunately, I only write one day a week here at Black Gate. Consequently, the odds that an anniversary of one of the handful of writers I hold in high esteem should fall on a Tuesday aren’t high enough that I can consistently write commemoration posts on the day in question. Sometimes, like last week’s post about Fritz Leiber (which proved surprisingly popular, if the comments it generated are any indication – thank you), the calendar cooperates somewhat and my post can appear a day before or a day after the intended date. It’s a bit of a cheat, but not one so egregious that my over-developed sense of propriety feels it’s “wrong.”

January is the birth month of multiple writers I esteem highly. As fate would have it, the birthdays of two of them happen to fall on Tuesdays in 2015, which makes my job a lot easier next month. In a couple of other cases, though, the birthdays fall on days of the week far enough away from my regular slot that I really do feel as if I’d be acting out of turn by devoting a post to them. Yet, in both of these cases, the author is such a colossal figure in the field of fantasy – never mind in my own personal pantheon of fantasists – that it would seem wrong to let his birthday pass without comment.

This long-winded preface is my way of saying that, while J.R.R. Tolkien’s 123rd birthday isn’t until this coming Saturday (January 3), this post is nevertheless about him and the incredibly long shadow he has cast over the field of fantasy fiction. Indeed, it is not an exaggeration to say that, for good or for ill, the contemporary popular understanding of what fantasy is derives almost entirely from his novels The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. I can scarcely think of another author whose idiosyncratic vision has so transformed the commonplace conception of the genre in which he wrote that it is now seen as not merely normative but exhaustive.

Which is why I’m now going to spend a few hundred words considering just a few of the things fantasy (and fantasy gaming) owe largely, if not necessarily exclusively, to Tolkien.

1. Orcs: Until I played Dungeons & Dragons, I’d never heard the word “orc” before (that’s not strictly true, as I recall that some of the monster books I read as a young child talked about sea monsters called “orcs,” but these were a whole ‘nother kettle of fish). And of course, the only reason D&D included orcs is because of Tolkien. Over the years, the portrayals of some post-Tolkien orcs have diverged from those of Middle-earth, but, even so, the word itself would likely never have entered into common use without The Lord of the Rings. I’d also argue (albeit with some trepidation) that Tolkien’s orcs established the template for a species of irredeemably evil monsters that fantasy has created in large numbers over the decades.

1. Orcs: Until I played Dungeons & Dragons, I’d never heard the word “orc” before (that’s not strictly true, as I recall that some of the monster books I read as a young child talked about sea monsters called “orcs,” but these were a whole ‘nother kettle of fish). And of course, the only reason D&D included orcs is because of Tolkien. Over the years, the portrayals of some post-Tolkien orcs have diverged from those of Middle-earth, but, even so, the word itself would likely never have entered into common use without The Lord of the Rings. I’d also argue (albeit with some trepidation) that Tolkien’s orcs established the template for a species of irredeemably evil monsters that fantasy has created in large numbers over the decades.

2. Elves: Prior to my reading The Hobbit, elves were (mostly) these weird little men who made wondrous stuff, whether it was Christmas toys or Fudge Stripe cookies. Although I knew of the álfar from reading Bulfinch, I didn’t really think of them as “elves,” a term I reserved almost exclusively to short guys in funny hats and pointy shoes. It took Tolkien to bridge the gap between the two and, since then, it’s been hard for me – and, I suspect, generations of fantasy fans – to think of Ernest J. Keebler and Elrond as having much of anything in common. It’s true that writers like Poul Anderson made use of the álfar concept independently of Tolkien (and to good effect, I might add). However, I’d happily wager that it’s from the good Professor’s works, not from Three Hearts and Three Lions, that contemporary notions of elfdom spring.

3. Dwarves: The very fact that most of you read this word and didn’t scream, “It’s dwarfs!” like good grammarians is evidence of just how much influence Tolkien has had on this subject. As with the elves, I originally had a much more fairy tale notion of dwarves, one that, leaving Disney’s Snow White to the side, was generally negative, if not outright sinister. Couple this with what I knew of the Nibelungenlied (again, thanks to Bulfinch) and I had a very different idea of what a “dwarf” was prior to reading The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. I would say that, unlike elves, the popular imagination of dwarves prior to Tolkien wasn’t that far removed from their Middle-earth cousins. Still, the heroic (if crusty) and battle-hardened smiths of short statue we see nowadays are Thorin Oakenshield’s descendants, not Alberich’s (never mind Dopey’s).

3. Dwarves: The very fact that most of you read this word and didn’t scream, “It’s dwarfs!” like good grammarians is evidence of just how much influence Tolkien has had on this subject. As with the elves, I originally had a much more fairy tale notion of dwarves, one that, leaving Disney’s Snow White to the side, was generally negative, if not outright sinister. Couple this with what I knew of the Nibelungenlied (again, thanks to Bulfinch) and I had a very different idea of what a “dwarf” was prior to reading The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. I would say that, unlike elves, the popular imagination of dwarves prior to Tolkien wasn’t that far removed from their Middle-earth cousins. Still, the heroic (if crusty) and battle-hardened smiths of short statue we see nowadays are Thorin Oakenshield’s descendants, not Alberich’s (never mind Dopey’s).

4. The Dark Lord: I’ve ranted in many places about the tendency in fantasy fiction to include an Ultimate Evil, the defeat of whom forms the basis for its narratives. It’s not that I object to such a narrative – I don’t – but rather that I object to seeing it reduced to a banal cliché. I don’t blame Tolkien for what his imitators have wrought, but I don’t think it’s at all unreasonable to say that, without Sauron, we’d never have seen Lord Foul, Shai’tan, the Warlock Lord, and Voldemort, among many others.

5. Trilogies: I enjoy playing the pedant and one of my favorite topics about which to be pedantic is the fact that The Lord of the Rings is not a trilogy. Tolkien wrote it as a single long novel, which his publishers split into three volumes for purely pragmatic reasons. Most people tend to think of it as a trilogy, in part because many of Tolkien’s imitators aped even the publishing format of his novel, thereby popularizing it to such an extent that any grouping of three is now regarded as a trilogy. Like Dark Lords, I don’t have anything against trilogies (or even longer multi-book series) if they’re done well, which is to say, serve a purpose other than simply conforming to an expectation that “fantasy literature must consist of a series of interminably long novels grouped into threes or more.” Almost as much as including elves or dwarves, being a trilogy is now shorthand for “this is what fantasy is.”

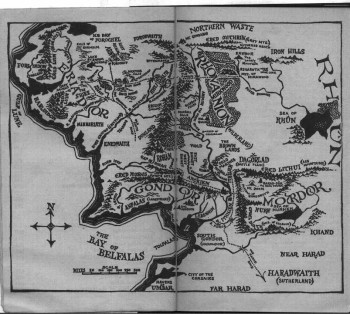

6.  World Building: Lest it seem as if all I’m doing in this post is complaining, I’d like to conclude with pointing out that it was Tolkien who established a standard for literary world building that has reigned ever since. I remember well my first encounter with The Lord of the Rings. The maps it included inside the covers enthralled me and I probably spent more time staring at them than I did any other section of the book – except perhaps the appendices, with their extensive timelines, family trees, and discussions of names, languages, and alphabets. Until then, I had never come across a book like this. Sure, I’d seen maps in books before, but most of them seemed halfhearted or whimsical rather than indicative of deep thought and care on the part of the author. I’d also encountered books where the author included snippets of imaginary languages, but that’s all they were – snippets. What Tolkien had done was of an order greater and more sublime than anything else I’d come across.

World Building: Lest it seem as if all I’m doing in this post is complaining, I’d like to conclude with pointing out that it was Tolkien who established a standard for literary world building that has reigned ever since. I remember well my first encounter with The Lord of the Rings. The maps it included inside the covers enthralled me and I probably spent more time staring at them than I did any other section of the book – except perhaps the appendices, with their extensive timelines, family trees, and discussions of names, languages, and alphabets. Until then, I had never come across a book like this. Sure, I’d seen maps in books before, but most of them seemed halfhearted or whimsical rather than indicative of deep thought and care on the part of the author. I’d also encountered books where the author included snippets of imaginary languages, but that’s all they were – snippets. What Tolkien had done was of an order greater and more sublime than anything else I’d come across.

Nowadays, though, almost everything Tolkien has included has become de rigeur. Crack open any mammoth tome of fantasy and there’s a very good chance you’ll find maps, histories, family trees, etc. etc. That’s all there because of Tolkien, who showed just how valuable it can be to create a setting with the same attention an author normally reserved for his characters. That’s not to say other authors hadn’t done similar things (E.R. Eddison and Robert E. Howard come immediately to mind), but it was Tolkien whose works demonstrated the value of it in a way others hadn’t. While I’m not an indiscriminate lover of such an approach – not every fantasy story needs, let alone deserves, this level of attention – I do think a good thing that writers of fantasy spend time giving some thought to the worlds in which their stories take place. Here’s hoping more of them don’t feel the need to keep trodding the same ground as J.R.R. Tolkien.

I read something somewhere a long time ago (so please forgive the paraphrase as I have no idea what the source was) that all fantasy written since the 1960s is either an imitation of Tolkien or a reaction against him.

I think that’s a bit of oversimplification, but he does cast a long shadow over the genre. In spite of all the poor imitations, I hate to think what the genre would be like without him.

I’ll be commemorating the Professor’s birthday this January as I usually do: http://www.mcmenamins.com/events/121176-Happy-Birthday-JRR-Tolkien

Agree to an extent. While most of what he did was hardly new, he popularised it to the extent it has become a standard template. Had a chuckle at the trilogy. I never realised LOTR was written as single novel. Actually thought it was other way, 5 books and a big confusing appendix (euphemism for cross selling Silmarillion etc) which publisher decided to put into trilogy format.

Orc’s origins go way back, there was discussion on RuneQuest rules list re this a few years ago, I can’t recall the agreed origin, but for sure reckon without Tolkien they may have remained some obscure figure or been relegated to the mischievous goblins of Enid Blightons Noddy stories.

You forgot to mention dragon hoards? Also the son making money off fathers ideas – Christopher Tolkien and the unfinished grocery lists etc:)

I don’t want to imagine a world without Tolkien. I wouldn’t necessarily be opposed, however, to a world without some of the first- and second-generation imitators, or at least a world where those imitators didn’t achieve such tremendous commercial success, thus helping to fix the boundaries of the genre.

I’m rereading The Sword of Shannara (purely for scientific purposes) , perhaps the first book which simply could not exist without JRRT

@ Fletcher – I have been tempted by that same scientific enquiry argument. So far I have resisted, but it would be interesting to read about your findings.

[…] Maliszewski speculated earlier this week what the world would be like if Tolkien hadn’t written The Lord of the Rings. I’ll not […]