Re-reading Michael Moorcock’s The History of The Runestaff: What I Missed the First Time Around

I don’t do re-reads, not often anyway. I’m usually too busy fighting neo-Nazis in the far future and wrestling dinosaurs on Mars. (You know, normal, everyday sort of stuff.) I decided to make an exception for The History of the Runestaff, however, mostly because I realized I had been recommending the thing to friends for years, but hadn’t touched it since I was twelve, when one of my friends dug the omnibus edition out of some weird corner in our school’s library, plopped it into my hands and mumbled something about multiple universes.

I don’t do re-reads, not often anyway. I’m usually too busy fighting neo-Nazis in the far future and wrestling dinosaurs on Mars. (You know, normal, everyday sort of stuff.) I decided to make an exception for The History of the Runestaff, however, mostly because I realized I had been recommending the thing to friends for years, but hadn’t touched it since I was twelve, when one of my friends dug the omnibus edition out of some weird corner in our school’s library, plopped it into my hands and mumbled something about multiple universes.

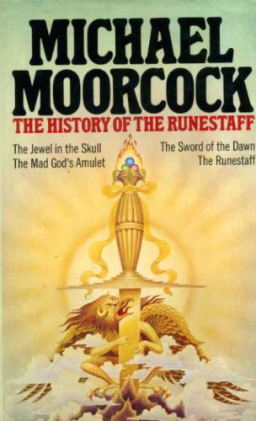

I remember staring, wide-eyed, at the thing, fascinated; the Conan covers might have been brutal and bloody and prominently featured big burly men, but this was strange, this was something different entirely; its pulsing yellows and light greens were alien, steeped in the psychedelia of the sixties (which, as the inside of the book told me, was when the books were written), it completely dashed away my expectations, crushed them under an iron-clad boot, made my little eyes wide. It contrasted brilliantly with the pulsing purples and browns and blacks of the Conan covers, its swirling surrealism was as far away from Frazetta as I had been.

Despite all that, I didn’t get around to actually reading it until a few months later, when my friend convinced the librarian to delete the book from the school files and I, somehow, managed to get him to trade me it for a copy of some other book. So it wasn’t until a few months later that I discovered that it wasn’t actually that different from Conan, anyway.

The History of The Runestaff was what introduced me to sword and sorcery, what truly opened the gate to Fritz Leiber, Edgar Rice Burroughs, David Gemmel, Jack Vance, Karl Edward Wagner, and so many others; it was, ultimately, what led me here. If there’s anything I’m going to re-read, I thought, it should be this.

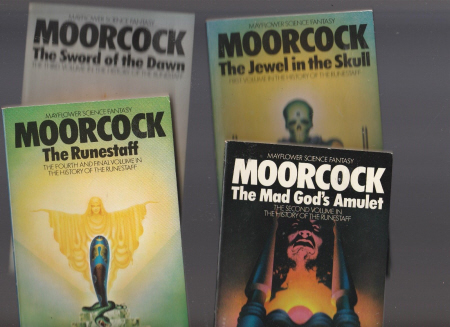

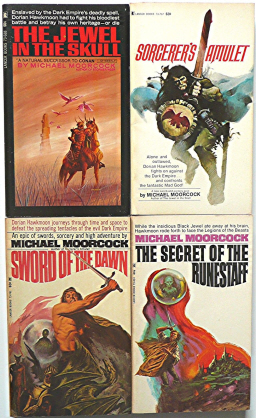

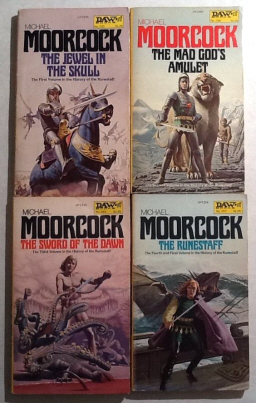

Although most people reading this will probably be familiar with the series, I think I better sum it up. The History of the Runestaff is made up of four novellas: The Jewel in the Skull, The Mad God’s Amulet (also published as Sorcerer’s Amulet), The Sword of the Dawn, and The Runestaff, all of which recount Dorian Hawkmoon’s struggle against the Dark Empire.

Yes, I know it sounds unbearably cheesy, but thanks to seventy metric tonnes of imagination on Moorcock’s part, relentless pacing, and a world teeming with melancholy and mystery, it never reads like that. It doesn’t always feel fresh, but it rarely descends into cliché (dialogue aside).

Yes, I know it sounds unbearably cheesy, but thanks to seventy metric tonnes of imagination on Moorcock’s part, relentless pacing, and a world teeming with melancholy and mystery, it never reads like that. It doesn’t always feel fresh, but it rarely descends into cliché (dialogue aside).

As for the setting, it’s actually one of the best parts of the series, an aspect I didn’t quite appreciate the first time around. Here a distant and cataclysmic event only ever referred to as the tragic millennium (no, there are no prizes for guessing what it is, shut up), has contorted the landscape and forced new, pre-industrial societies to rise up out of the ashes. It’s still pseudo-medieval, though, because sword fights.

Here, pseudo-science and mysticism intertwine above the desolate wastes of a new world and the lost, shimmering cities of the old one. It’s as beautiful as it is strange, as teeming with mystery as it is bursting with horror. It’s sad and poignant in its own special way, in its vague descriptions and subtle ambiguity. There’s sadness in its shimmering cities, the kind you have to find for yourself sometimes.

And it’s home to one of the best sets of villains in sword and sorcery: The Dark Empire of Gran Bretan. They don’t really rewrite the Dark Empire rulebook, they just do what they do really well, they aren’t morally ambiguous, in fact they seem to self-identify as evil; torture is central to their culture, they aren’t particularly ambiguous, and there doesn’t really seem to be a thinking, feeling soul among them; no one in Gran Bretan, save a few, are anything more than automatons, there because Dorian Hawkmoon needed someone to beat up.

But they are delightfully decadent and intensely interesting. It’s a culture as capable of beauty and art, science and literature, as it is the perverse and the cruel; it’s capable and willing to twist that art and corrupt its science. Where Tolkien’s orcs were brainless, snarling cockneys, the soldiers of Gran Bretan are cultured, professional, and intelligent; the Uruk-hai captains might have had big muscles and flesh pits, but the nobles of Gran Bretan are eccentrics and gentlemen, hiding their cunning and their spite behind ornate masks and silver tongues. You know, when the good guy isn’t chopping their heads off.

But they are delightfully decadent and intensely interesting. It’s a culture as capable of beauty and art, science and literature, as it is the perverse and the cruel; it’s capable and willing to twist that art and corrupt its science. Where Tolkien’s orcs were brainless, snarling cockneys, the soldiers of Gran Bretan are cultured, professional, and intelligent; the Uruk-hai captains might have had big muscles and flesh pits, but the nobles of Gran Bretan are eccentrics and gentlemen, hiding their cunning and their spite behind ornate masks and silver tongues. You know, when the good guy isn’t chopping their heads off.

I really don’t want to spoil much of the plot, because part of the joy of The Runestaff is discovering more of the world and the richness of it, but when you first read it, caught up in the relentless pacing and eagerly awaiting the next memorable moment (of which there are many), you don’t have time to acknowledge these things, to sit down and appreciate the brilliance of Gran Bretan. It’s such a shame though, that exploring this part of the world is so often neglected in favor of more sword fights.

Although, for me, the book gained a lot of richness upon re-reading, it also lost something. The sense of adventure, whilst it wasn’t absent entirely, was rather diminished. With a first reading, of course, there’s the sense that anything can happen on the next page, that, every time you open the book, a fresh, new and original adventure awaits you. With a re-reading, that’s all gone. That might be par for the course when you re-read anything, sure, but, here, a work of sheer imagination, here, where the sense of wonder and mystery were so prevalent, so central to the appeal of the books, it’s quite a considerable loss.

The relentless pacing of the novels began to wear on me after a while, too; it got to the point where I’d start to zone out during the innumerable battles. Hawkmoon chopping off a baddie’s head became as routine as toast and coffee in the morning.

Don’t get me wrong, the battles are still memorable and gory, possessed of that lovely yet, somehow, intangible crunch all those good fantasy novels have, whenever Frank the faceless goon gets his big thick skull smashed in. It’s just that there are so many of them that they all start to blend together after a while; it doesn’t matter so much when you’re twelve, but after that, you start to pine for other, more substantial things, like a touch of atmosphere or a bit of character development maybe — one not drawn from Moorcock’s big ol’ book of stock characters.

Don’t get me wrong, the battles are still memorable and gory, possessed of that lovely yet, somehow, intangible crunch all those good fantasy novels have, whenever Frank the faceless goon gets his big thick skull smashed in. It’s just that there are so many of them that they all start to blend together after a while; it doesn’t matter so much when you’re twelve, but after that, you start to pine for other, more substantial things, like a touch of atmosphere or a bit of character development maybe — one not drawn from Moorcock’s big ol’ book of stock characters.

I know I’m usually the one who pines for ceaseless action, but there’s a middle ground, and The Runestaff series crosses it, hijacks a military jet plane, bombs the Chinese, and parachutes out, all whilst playing a rock guitar solo with its tongue.

Something has to be said for Hawkmoon, though; upon first reading the book, he seems like a generic, noble hero, chivalrous and brave and determined and all that, and that’s how my young, naïve little brain imagined him, but reading of him now, with more experienced eyes, he gains a little something more. Personally, I see a rather slight, subtle insanity in Hawkmoon’s actions; a lot of what he does isn’t really dictated by rational thought, but by sheer emotion, and, the first part of the first book aside, he never appears disheartened or hopeless, even when the situation has taken a turn for the worse, he fights with reckless abandon, in terms of both his own life, and the lives of his friends , to the point where he doesn’t seem to care who lives and who dies at the end. There isn’t a problem he’s faced with that he doesn’t try to resolve by hitting it with a sword.

It all reaches a point where, during his brief respite at Castle Brass (a safe haven from the empire) he gets grouchy because he hasn’t killed enough people, and starts hankering for those bygones days of blindly wandering around the continent and sleeping in puddles of his own urine and patches of dirt like some sword-wielding Bear Grylls, all in some vain attempt to stop the Dark Empire.

He’s a character almost physically reliant on battle and struggle, a madman and an extremist, almost as dangerous as his enemies. He certainly isn’t likeable when you realize this, he’s quite the ass, actually, but it makes him more interesting as a character, someone you want to read about more than ‘muscular fantasy man number 876’.

Oh, and the finale is fantastic — even better then I remember it. It’s rather dissonant with the pulpy charm of the rest of the series, but it really is a highlight. Spoilers coming up, by the way, so lob your computer down a flight of stairs if you haven’t finished the first series yet; you should have done though, the books have been out since the sixties and it’s not like they’re particularly difficult.

Oh, and the finale is fantastic — even better then I remember it. It’s rather dissonant with the pulpy charm of the rest of the series, but it really is a highlight. Spoilers coming up, by the way, so lob your computer down a flight of stairs if you haven’t finished the first series yet; you should have done though, the books have been out since the sixties and it’s not like they’re particularly difficult.

You guys know Oladahn, right? that chummy little midget thing that reminded me of my little black staffie sometimes? He dies unseen and unheralded, chopped down by countless axes and swords mere meters away from his only friends, for a cause he hadn’t even heard of months before. Or then there’s Hawkmoon’s friend, Huilliam D’averc’s death: he cuts his way through the palace of Gran Bretan, reunites with his only love mere moments before a guard burns him alive in front of her, a guard who then goes on to claim, self-importance dominating his tone, ‘You’re safe now, madame.’

It’s moments like these, moments of understated sadism, of morose humor, that truly elevate the finale above the rest of the book, that shout that nothing meaningful is attained without sacrifice. It’s moments like these that stand as moving, mature, and poignant in a series that had been, up until this point, dedicated to jolly sword fighting fun. Dissonant, sure, but taken on its own terms, it’s bloody marvelous.

It’s a testament, though, to the brilliance of this book that, re-reading it a second time yields another 2,000 words or so of discussion. It really is the hallmark of a classic when you can go back to a book and discover secrets and suggestions you missed the first time around entirely, because, yes, The History of the Runestaff, for all its flaws, is a classic, managing to somehow fuse chirpy adventuring with slight, subtle melancholy.

In between all the sword fights and giant robot monster things, Moorcock still finds time to treat you like an adult and, through characters like Orland Fank, places like the silver bridge, the big science city thing near Mygan’s cave, and the hallucinogenic beauty of the Runestaff’s home, he forces you to come up with your explanation for things and the experience becomes all the richer for it. Michael Moorcock may have been making it up as he went along, but then so was God, probably.

Great review. I reread The Jewel in the Skull myself a few years ago and was equally surprised how well it held up. Not bad for a book written in like a weekend.

How much of the Dark Empire of Gran Bretan was subsumed into the Imperium of Warhammer 40,000? (In terms of influence, that is.)

I’m about halfway through the books at the moment – it’s over thirty years since I last read them – and found it interesting how they differed from, say, the first Corum Trilogy. The latter has a certain, trippy psychedelic quality. This is its chief selling point for me. The downside is that the storyline is sometimes choppy and fragmented. The Hawkmoon books have a couple of core motifs – ie, the Kamarg and the masked Granbretan. Their chief selling point is their forward momentum rather than their visual inventiveness. I admit I’m beginning to flag (all that non-stop action can get a bit wearing after a while) but would put this down to my age as I think they’re best suited to a younger demographic. Still pretty good, though!

Moorcock: plot, plot, plot. Kill the bad guys. You’re spot on that Gran Bretan seems to exist entirely for Hawkmoon to battle. I’ve got probably all of his sword and sorcery Eternal Champion titles on the shelf in one form or another, but most won’t get opened again by me. The exception, which I’ve written about here before: The War Hound and the World’s Pain, along with a related Von Bek story or two. Those, for me, still sing.

Hi Fletcher

I thought the Jewel in the Skull held up pretty well, too, but not nearly as well as The Runestaff or The Sword Of The Dawn, at least in my opinion. I’m you enjoyed the review, though. 🙂

Hi Joe,

I don’t know too much about Warhammer, but I’d agree in that they have similar feels, if that makes sense. Plus, I think the emperor in the Warhammer universe is like, exactly the same as King Emperor Huon from The History of The Runestaff. You can feel its influence in a fair few things, actually, like in this video game I’ve been playing recently called Dark Souls (I wrote an article on it a while back, actually) and there are a pair of bosses that are almost the spitting image of Shenegar Trott and Baron Meliadus. I might have to make a post out of this, someday.

Hi Aonghus Fallon,

Yeah, the action can tire you down after a while, it’s a book best read in short bursts if you’re not a coked up ten year old. I enjoyed the Corum trilogy, though but they got a little too trippy for me after a while 🙂

Hi Mark.

I think you mentioned The War-hound and The World’s pain back when I reviewed it ages ago. I liked it, but, I can’t bring myself to see it as the best Moorcock’s ever done, it just lacks a little something for me. 🙂

I grew up reading (and re-reading) Moorcock’s Elric series several times over. But I read the Hawkmoon series for the first time last year.

I have to say that I really enjoyed Hawkmoon. It reminded me a lot of the Elric books. And I love Moorcock’s imagination when it comes to empires, cities, and monsters.

Much of what you say, in terms of criticism, is spot on though. Nevertheless, I’ll probably pick this series up again before I do Elric. Sometimes old fashioned sword and sorcery is just what I’m in the mood for.

I’m currently revisiting Elric (for the Sword & Sorcery book club on Goodreads) and I have to say that although I can definitely see more … imperfections than when I was in high school, I’m still enjoying them.

One of the reasons Moorcock still holds up for me is that Dorian Hawkmoon Elric Corum Erekosë, both in terms of the characters and the worlds they inhabit. The broad structures (lone hero against the forces of Evil/Chaos) may be similar, but the details most certainly are not, and it’s all about the details …

Hi James

I understand what you mean, sometimes you get that itch that only classic S&S can scratch, and I love Moorcocks imagination, I’ve mentioned it a tonne of times, and I think it’s one of his greatest traits.

Hi Joe

I think the overarching structural similarities are sort of key, and mark the eternal champion stories as stories that take part in the same universe, but as you say, the details make all the difference. I think it’s that, though; the basic structure, supported by minuscule and unique details means the eternal champion series has something for pretty much anybody, and it means no two stories or two fans are really the same. It’s one of those things, that lets me know I’m reading Moorcock, and that everything will be not terrible for a little while. 🙂

(And now that I read my previous comment, I see that it dropped some characters — it was supposed to be “Dorian Hawkmoon is not Elric is not Corum is not Erekosë”.)

[…] Re-reading Michael Moorcock’s The History of The Runestaff: What I Missed the First Time Around […]