The Fantasy Roots of Fan Fiction

My fifteen year-old daughter is a voracious reader. I thought I read a lot, but I’m not even in her league. She reads fairy tales, a great deal of YA fantasy, and a smattering of horror. Just a few days ago, she asked me where to find Stephen King in our library. I wonder if that means she’s finally going to stop re-reading The Hunger Games.

My fifteen year-old daughter is a voracious reader. I thought I read a lot, but I’m not even in her league. She reads fairy tales, a great deal of YA fantasy, and a smattering of horror. Just a few days ago, she asked me where to find Stephen King in our library. I wonder if that means she’s finally going to stop re-reading The Hunger Games.

But mostly what she reads is fan fiction. I mean, a ton of fan fiction. She reads it online on her Kindle, curled up on her bed. Walking Dead fanfic, Buffy fanfic, Harry Potter fanfic, Fairy Tail fanfic… I know all this because every time she reads something she really likes, she comes bounding downstairs to breathlessly relate the details. Having trouble communicating with your teenage daughter? Here’s a tip: shut the hell up and listen when you’re drying dishes, or trapped with her on a long road trip. I think I can name every character on The Walking Dead, and I’m not sure I’ve ever seen an episode.

Anyway, the point is, my daughter treats fanfic with the same respect and enthusiasm as published fiction. It’s fully legitimate to her. There’s also a certain sense of ownership — her friends read fan fiction, but she doesn’t know any adult who does, so there’s a generational divide. Fanfic belongs to her generation, the way Dungeons and Dragons and Star Wars belonged to mine. Part of her love for fan fiction stems from the fact that her generation is the first to really discover it.

Except it’s not, of course. Not really. Yes, the explosive growth in the fan fiction community is relatively new, but the phenomenon is not. I’ve been thinking about this a lot recently, and it all stems from a comment Fletcher Vredenburgh made in his review of Lin Carter’s Kellory the Warlock:

Most of his fiction, rarely more than pastiches of his favorite authors (Howard, Burroughs, Lovecraft, and Dent), never garnered enough attention to be republished… Most of the time, he was trying to create fun, quick reads that were recreations of his favorite writers. In a way, he was writing fan fiction; it’s just that he got his published.

I think this is fairly astute. I think Lin Carter might be more appreciated today if he were reassessed for what he truly was: an imaginative and extremely prolific fanfic writer. The same is true of many other writers, in fact, who are long out of print and in danger of being forgotten, including L. Sprague de Camp, Andrew J. Offutt, August Derleth, and even folks like Karl Edward Wagner.

Playing around in someone else’s sandbox (called the pastiche in writing circles) has a long and respected history in fantasy, in fact.

The father of the modern fantasy pastiche is L. Sprague de Camp, who made a multi-decade career reworking Robert E. Howard’s Conan. We know Howard spent four years writing Conan stories, from 1932 to 1936, producing roughly three book’s worth in the process. In the two decades de Camp spent writing Conan, he produced far more than Howard did: six full-length novels and a dozen collections, mostly in collaboration with other writers like Björn Nyberg and Lin Carter.

The father of the modern fantasy pastiche is L. Sprague de Camp, who made a multi-decade career reworking Robert E. Howard’s Conan. We know Howard spent four years writing Conan stories, from 1932 to 1936, producing roughly three book’s worth in the process. In the two decades de Camp spent writing Conan, he produced far more than Howard did: six full-length novels and a dozen collections, mostly in collaboration with other writers like Björn Nyberg and Lin Carter.

When de Camp died, his brand of Conan story quickly fell out of favor, and his Conan pastiches are not highly regarded today — certainly not when compared with the brilliant work of Robert E. Howard, anyway. But there’s little disputing the fact that he kept the property alive for several decades, and without de Camp, it’s possible the name Conan (or even Robert E. Howard) wouldn’t be nearly as well known today.

De Camp did far more than keep one character alive, however. What he legitimized, in fact, was the pastiche novel itself. Pastiches have existed for as long as fiction itself, of course, but De Camp was one of the first to turn it into a real industry, and his success led many others to follow his lead.

Between 1955 and the end of the 20th Century, some 53 Conan pastiche novels were published, from a wide range of publishers. Counts vary, but by my reckoning the most prolific Conan pastiche writers were:

Leonard Carpenter — 11

John Maddox Roberts — 8

Robert Jordan — 7

Roland J Greene — 7

Steve Perry — 6

L. Sprague de Camp — 6

Andrew J Offett — 2

Sean A Moore — 2

John C. Hocking — 1

Karl Edward Wagner — 1

Poul Anderson — 1

That’s a pretty impressive list. And it’s not even including the short stories (many expanded from fragments left behind by Robert E. Howard) collected and edited by De Camp in his dozen Conan collections.

As long as we’re giving de Camp credit for keeping Conan alive and in the public eye, we should probably ask the question: would Robert Jordan have had a career in fantasy if he hadn’t gotten his start writing Conan pastiches? I doubt it. Fan fiction rejuvenated de Camp’s career, and I think we also have it to thank, ultimately, for the top-selling American fantasy series, Jordan’s The Wheel of Time.

While de Camp may have had a very successful career writing what amounted to Robert E. Howard fan fiction for over two decades, even that accomplishment pales in comparison to his protégé, Lin Cater.

While de Camp may have had a very successful career writing what amounted to Robert E. Howard fan fiction for over two decades, even that accomplishment pales in comparison to his protégé, Lin Cater.

De Camp took Carter under his wing very early in his career, and they edited five of the Conan anthologies together. Carter quickly took his mentor’s example to heart. He produced dozens of novels and short stories, the vast majority of which were openly derivative of writers he admired, including his Thongor the Barbarian series (drawn liberally from Edgar Rice Burroughs and Robert E. Howard), the Callisto books (Burroughs’s Barsoom novels); the Zanthodon series (Burroughs’ Pellucidar), the four Mysteries of Mars books (Leigh Brackett), and his Prince Zarkon novels (Doc Savage).

I wrote about the last of Carter’s Mysteries of Mars novels, Down to a Sunless Sea, just last week. In the Author’s Note for that book, Carter shared the source of his inspiration:

Actually, the only link of continuity between these four books is that they are laid on the same version of Mars – which was obviously (as the knowledgeable reader, who is an author’s bliss, will easily have realized) shaped and influenced to a considerable degree by Leigh Brackett’s marvelous series of Martian adventure stories which were published in such science fiction magazines as Startling Stories and Planet in my early to middle teens.

Those yarns had wonder titles like “Shadows Over Mars” (which Don Wollheim, then at Ace Books, reprinted as The Sword of Rhinannon) and “Sea-Kings of Mars,” and so on. When I came to create my own version of Mars I was inescapably reminded of hers, and strove to write my novels in something resembling her lean, sinewy prose, which I have always admired and thought excellent.

In addition, Carter wrote a great deal of Cthulhu Mythos fiction (pastiches of H.P Lovecraft), as well as pastiches of Clark Ashton Smith and Lord Dunsany.

With two such influential writers shaping their entire careers around fan fiction — excuse me, pastiches — it’s no surprise that the concept quickly became accepted in the industry.

Andrew J. Offutt built a career on sword & sorcery pastiche novels (especially Conan and Cormac Mac Art), and others followed, including Karl Edward Wagner (Conan and Bran Mak Morn), Richard Lyon and David C. Smith (Red Sonja), and many others.

In fact, sword & sorcery became so closely associated with the pastiche novel in the mid-70s through the early 90s that for a while the terms seemed almost synonymous. As Ryan Harvey, who reviewed several Conan pastiches from this period for us in his Pastiches ‘R’ Us series, noted:

In fact, sword & sorcery became so closely associated with the pastiche novel in the mid-70s through the early 90s that for a while the terms seemed almost synonymous. As Ryan Harvey, who reviewed several Conan pastiches from this period for us in his Pastiches ‘R’ Us series, noted:

When I first started reading Howard’s Conan stories in the early ‘90s, the only place I could easily locate them was in the paperback series that mixed pastiche stories among Howard’s originals… Most Howard fans would never touch them, but Conan novels were, at the time, one of the few places to buy genuine sword-and-sorcery at a standard chain bookstore.

Ironically then, it was Conan fan fiction that introduced a new generation of young fans to sword & sorcery and, eventually, led them to rediscover Robert E. Howard.

While we’re on the topic of Ryan’s reviews, I have to credit him with tipping me off to some of the more interesting Conan pastiche novels, including a few I probably would never have given a second glance. Here he is on the entirely gonzo Conan and the Treasure of Python by John Maddox Roberts (Tor, 1992):

The editors should have renamed this book Conan and the Treasure of King Solomon’s Mines. This isn’t a case of borrowing or inspiration the way that, for example, Forbidden Planet borrows from The Tempest, or The Warriors draws inspiration from Xenophon’s Anabasis. No, this novel is literally King Solomon’s Mines: John Maddox Roberts copies the exact plot of the classic H. Rider Haggard 1885 adventure novel and recasts it as a Conan story, with the legendary barbarian starring in the Allan Quatermain role. The story similarities are striking, pervasive, and go far beyond coincidence or subconscious borrowing. The overall structure of both books is beat-for-beat identical.

And, because I can’t resist, here’s Ryan on L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter’s Conan of the Isles (Lancer, 1968):

I’ve neglected the earlier Conan pastiches, from publishers Lancer (Sphere in the U.K., later Ace in the U.S.) and Ballantine. Before Tor started its Conan factory with Robert Jordan’s Conan the Invincible, the world of Conan pastiches rested mostly in the hands of two men: L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter… One of the results of de Camp and Carter’s addenda to Conan’s history is the odd, uncharacteristic, yet hypnotically entertaining Conan of the Isles.

As popular as Howard pastiches were at the end of the 20th Century, I think they’ve been eclipsed by the recent surge in popularity of the Lovecraft pastiche. Just in the last year we’ve covered at least a dozen new Lovecraft-inspired novels, anthologies, and comics here at Black Gate, including the just released The Madness of Cthulhu. And the truly hardcore can enjoy fiction inspired by both Robert E. Howard and H. P. Lovecraft, in books like the recent Sword & Mythos.

As popular as Howard pastiches were at the end of the 20th Century, I think they’ve been eclipsed by the recent surge in popularity of the Lovecraft pastiche. Just in the last year we’ve covered at least a dozen new Lovecraft-inspired novels, anthologies, and comics here at Black Gate, including the just released The Madness of Cthulhu. And the truly hardcore can enjoy fiction inspired by both Robert E. Howard and H. P. Lovecraft, in books like the recent Sword & Mythos.

Of course, sword & sorcery and Lovecraft pastiches weren’t the only avenues for fan fiction in the early 20th Century.

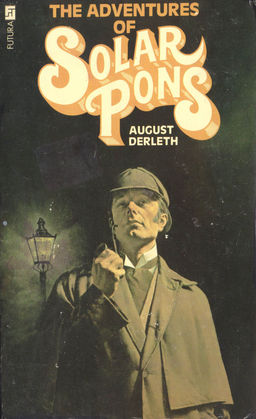

August Derleth, who began his career writing H.P. Lovecraft pastiches — indeed, who arguably legitimized it in the way L. Sprague de Camp legitimized Conan fan fiction — quickly branched out to Sherlock Holmes pastiches with the very successful Solar Pons (I couldn’t figure out the connection between Solar Pons and Arthur Conan Doyle’s more famous creation, until I said the name “Solar Pons” out loud.)

The Sherlock Holmes pastiche, in fact, is an entire cottage industry in itself. You may think 53 Conan pastiche novels is a lot, but I seriously doubt any literary creation in the English language has spawned as many pastiches as Sherlock Holmes.

The “Best Sherlock Holmes Pastiches” poll at Goodreads currently includes a whopping 279 titles, just as an example.

I’m not a Solar Pons expert. However our Monday blogger, Bob Byrne, has promised an upcoming series on the character, and I’m looking forward to it.

There are other fine examples of 20th Century fan fiction/pastiche novels, but I think you get the point. You can trace the modern phenomenon of fan fiction directly to the tradition of the pastiche, and the way American fantasy (and especially sword & sorcery) depended on the pastiche to a very significant extent for several decades legitimized the form for an entire generation of young writers.

As successful (and essential) as it was, the fantasy pastiche never got a lot of respect, and I see the same situation with fan fiction today. Will that ever change? It’s an interesting question. The best answer I can give you is to point to E L James’s Fifty Shades of Grey, perhaps the biggest publishing phenomenon of the last half decade. Fifty Shades of Grey began life as Twilight fan fiction, before it was cleaned up and re-written for broader publication.

Will fan fiction ever get respect? I think respect will come with success, and success in the publishing world means real dollars. Fan fiction, by its nature, isn’t sold — it’s given away. But one mammoth success has already broken out of the fan fiction science lab, and I think it’s only a matter of time until it happens again. Ignore fan fiction at your peril.

It’s not a issue in my case. I can’t ignore fan fiction — at least until my daughter leaves home. After that, I will doubtless have to find another way to keep current.

But by then, that will probably be the least of my worries.

Nice piece, John. There’s certainly a monstrously huge industry for Holmes pastiches/fan fiction. It’s been growing since the seventies and you just have to type his name in Amazon to be buried in non-Doyle stories.

The explosion of self-publishing, e-publishing and small market presses has probably resulted in more Holmes pastiches printed than for any other character/genre.

The biggest flaw (I think) with fan fics/pastiches is that a lot are simply bad. Because anybody can get their story online and even sold. There’s not much of an editorial filter any more. It just means you have to be choosy in what you buy/read. Caveat emptor.

Lately, I’ve been giving though to a series of stories based on a couple third edition D&D modules. Would that qualify as fan fiction?

My wife reads a lot of fan fiction as well. My opinion is that there are plenty of authors who have gone through the struggle that is getting your work published and they deserve to be read.

The counter argument to that is that you want to read stories about certain characters and the only way that’s going to happen is if you read fan fiction.

I’m always surprised by the amount of fan fiction that is out there. You would be challenged to find an IP that has been created in the past 40 years and doesn’t have fan fiction written about it.

I think licensed fiction is also a major thing to think of in this context. There are a lot of Star Trek novels and Star Wars really lives primarily from its novels and comics. Even the videogames provide far more material than the movies.

While there is some editorial oversight to keep things from not contradicting each other and avoiding overly controversial content, I believe those writers are still quite free with making up their own material.

My favorite things Star Wars are the X-Wing novels, KotOR comics, and Jedi Knight games, in which the heroes from the movies are almost completely absent and limited to a few cameo appearances.

Very thought provoking piece.

You make a good case for believing that fan fiction is not new and that it is indeed a valuable thing (regardless of whether it translates into dollars like Shades of Grey).

John, I love these sorts of posts. You do a wonderful job of pulling together seemingly disparate strands of thought on Blackgate and making insightful commentaries upon them. You’re like a sage who says, “Look what wisdom can be found here . . .”

> The biggest flaw (I think) with fan fics/pastiches is that a lot are simply bad. Because anybody can get their story online and even sold.

> There’s not much of an editorial filter any more. It just means you have to be choosy in what you buy/read. Caveat emptor.

Bob,

Indeed. That’s the primary drawback with fanfic, of course… it’s perceived as (and usually is) a step or three below profic.

On the other hand, the review systems set up at many of the big Fan Fiction sites (places like FanFiction.Net, etc.) allow a way for readers to vote up their favorites. Meaning you can spend your time reading the top 1-2% of fan fiction. It’s not a perfect system, of course, but it’s something.

> Lately, I’ve been giving [thought] to a series of stories based on a couple third edition D&D modules. Would that qualify as fan fiction?

Yeah, I think so, since you’re playing around with an existing setting (even if most the characters would be yours.)

I’m curious — which modules in particular?

> You would be challenged to find an IP that has been created in the past 40 years and doesn’t have fan fiction written about it.

Glenn,

Yeah, that’s true, although TV and anime seem to be generating by far the largest volume these days.

One thing I find encouraging is that so many young people seem to be pouring their energy into writing. Yeah, it’s fanfic, but it’s still a creative endeavor. Even my daughter has gotten into the act, spending hours writing short stories (and even a novel), and I think that’s neat. It’s better than spending hours playing computer games!

> I think licensed fiction is also a major thing to think of in this context. There are a lot of

> Star Trek novels and Star Wars really lives primarily from its novels and comics.

Martin,

Great point. I avoided media properties like Star Trek and Star Wars in my article, but maybe I shouldn’t have. They’re a different beast than the pastiche, which (in fantasy at least) usually arises from a writer hijacking another creator’s IP, often to create an homage.

Media properties, of course, are much more closely managed, with the controlling corporation selecting who will be writing the novels, and often providing guidance in some form. So there’s little of the sense of ownership (in the sense that pastiche writers feel entitled to continue the stories of their favorite characters), or the wild west mentality of the pastiche in media fiction, in my opinion.

But you could probably make a case that modern fanfic really grew out of fans wanting to write (and share) their own Star Trek and Star Wars stories, rather than tracing its roots to S&S and Lovecrast pastiches at all. I don’t know enough to give a definitive answer.

> John, I love these sorts of posts. You do a wonderful job of pulling together seemingly disparate strands of

> thought on Blackgate and making insightful commentaries upon them.

James,

Thanks for the compliment! But really, credit here goes to Fletcher for making the original connection between Lin Carter and fan fiction. I’m just following that line of thinking to its logical conclusion.

In your list of pastiche authors that wrote Conan novels, you include one “John Wagner”. A typo, or is this an author that I have missed? By the way, great article; good pastiche deserves to be promoted just a little!

> The biggest flaw (I think) with fan fics/pastiches is that a lot are simply bad. Because anybody can get their story online and even sold.

> There’s not much of an editorial filter any more. It just means you have to be choosy in what you buy/read. Caveat emptor.

But that’s also true of anything that comes from the big publishers. I’ve picked up my share of dogs from the book store.

John, great article! Just to let you know, though, it’s inspired me to review more Lin Carter. 😉

As someone weaned on HPL and REH pastiches I’ve never been opposed to the idea of fan fiction. It’s all a matter of quality. Sometimes it’s Darrell Schweitzer writing Mythos stories and sometimes it’s Lin Carter.

I wonder if the growth of fanfic is related to the immersive nature of so much other entertainment these days. We’re used to becoming enveloped in comp games and 3-d movies. We’re inundated with DLC and JK Rowling telling us what happened to her characters later in life. We want to become lost in these things and writing new stories featuring beloved characters lets their authors become more intimately involved with them.

I think the answer to the question you raise about the roots of fanfic is probably that they do rest in Star Trek and not HPL and REH. The earlier writers were working with some tacit approval and the intention of being published. The ST writers were writing for themselves and other fans and working below the radar in ‘zines and message boards.

I totally get all of this interest and love for it. We don’t always want the adventure to end when we turn the last page. Can’t Conan slay one more Pict? I want to hear Holmes shout, “Come, Watson, come!” once more.

Conan is also an interesting case because of Bjorn Nyberg’s contribution — wasn’t The Return of Conan something he wrote essentially as a fan, then sent to de Camp and had included in the series?

I first learned about fan fiction when I was a teen in the mid 90’s. It was then that people really started putting it up online. Does anyone know of any fanzines that might have published fan fiction earlier than that?

John: Essentially, Necromancer Games’ ‘The Tomb of Abysthor.’ The whole concept incorporates elements and background history of The Wizard’s Amulet, the Crucible of Freya, Rappan Athuk, The Slumbering Tsar, Demons and Devils and Bard’s Gate. I like the depth of the storyline and the modules. They sprinkled in tons of stuff that can be teased out to add richness to stories.

Frog God Games is Pathfinderizing just about everything into their upcoming Lost Lands campaign setting.

http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&sqi=2&ved=0CB4QFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.froggodgames.com%2Flost-lands-stoneheart-valley&ei=XhRBVOHFGIiI8gHl4YDYBQ&usg=AFQjCNFtgapKchZM89EyNzKxjUMppmapjw&bvm=bv.77648437,d.cWc

> In your list of pastiche authors that wrote Conan novels, you include one “John Wagner”. A typo, or is this an author that I have missed?

Darkman,

Good catch! Looks like a typo; I’ve removed it.

I suspect it came from a cut and paste error while I was assembling the list… the two writers immediately before “John Wagner” on my list were John C. Hocking and Karl Edward Wagner. Looks like I slipped up at one point, and a magical book by “John Wagner” got added. Sorry about that!

> By the way, great article; good pastiche deserves to be promoted just a little!

Thanks!

> John, great article! Just to let you know, though, it’s inspired me to review more Lin Carter. 😉

Fletcher,

Glad to hear it! I think. 🙂

> I wonder if the growth of fanfic is related to the immersive nature of so much other entertainment these days.

> We’re used to becoming enveloped in comp games and 3-d movies. We’re inundated with DLC and JK Rowling telling us what

> happened to her characters later in life. We want to become lost in these things and writing new stories featuring

> beloved characters lets their authors become more intimately involved with them.

You could well be right; that’s an excellent point. The fact is, books and movies are no longer self-contained. Modern readers are constantly confronted with “the continuing adventures” of our heroes; that creates both an appetite and an expectation for a constant diet of entertainment. The step from that state to creating adventures of your own is much smaller than it used to be when books were completely self-contained events.

> I think the answer to the question you raise about the roots of fanfic is probably that they do rest in Star Trek and not HPL and REH.

Yeah, you could also be right here, but I’m not as convinced. Where did modern readers get the idea to write fanfic? Sure, STAR TREK and STAR WARS taught us that characters didn’t necessarily belong to their creators, and that’s a critical step in the psychology of fanfic. But they also taught us about licensed properties, and how permission to write those properties is a legal issue.

I think the example de Camp and Carter set is actually more important, because it completely circumvented the legal question. Carter never asked permission to write about Brackett’s Mars, or in Burrough’s world. He just did it, and the readers followed.

When some of the biggest writers on the planet – Stephen King, Robert Bloch, etc — write Lovecraft fiction, that legitimizes fanfic in a way that carefully licensed and controlled properties don’t, I think.

Still, none of this is provable, so it’s all a matter of opinion. Still, it’s a fascinating debate.

> Conan is also an interesting case because of Bjorn Nyberg’s contribution — wasn’t The Return of Conan something he wrote

> essentially as a fan, then sent to de Camp and had included in the series?

Joe,

Great question. I know nothing about Nyberg, actually, other than the fact that he’s Swedish.

Anyone else have an answer?

> Does anyone know of any fanzines that might have published fan fiction earlier than that?

Hi CMR,

I haven’t, but we’ve got one or two posts coming up that address the topic much better than I could. Stay tuned!

> John: Essentially, Necromancer Games’ ‘The Tomb of Abysthor.’ The whole concept incorporates elements and background history

> of The Wizard’s Amulet, the Crucible of Freya, Rappan Athuk, The Slumbering Tsar, Demons and Devils and Bard’s Gate.

Bob,

Sounds marvelous! Let us know if you get anywhere with it.

> Frog God Games is Pathfinderizing just about everything into their upcoming Lost Lands campaign setting.

This looks very intriguing… thanks for the link. Clearly I need to pay more attention to Frog God Games…

> But that’s also true of anything that comes from the big publishers. I’ve picked up my share of dogs from the book store.

Bobby,

Ha – very true! Although I think Bob’s point was that fanfic has a lower quality bar as a result of zero editorial control, and I don’t think anyone really argues that point.

“Giving de Camp credit for keeping Conan alive and in the public eye” is one of those cliches that does not hold up. A more accurate statement would be “De Camp took control of Conan” for his own personal gain. August Derleth put Conan into hardback first in the 40s, then Donald Wollheim in THE AVON FANTASY READER, then Martin Greenberg at Gnome Press. John D. Clark was the first editor for the Gnome Press book but de Camp inserted himself. Greenberg had inked a deal with Bantam Books to reprint the Gnome Press books in 1962. Why that did not happen is a mystery but it has the whiff of de Campian litigiousness about it. Oscar J. Friend, agent for the Howard copyright holders kept de Camp at bay but after he died, de Camp marketed the Conan series without contract from the copyright holders. Conan would have done just fine without L. Sprague de Camp.

[…] N (Black Gate) The Fantasy Roots of Fan Fiction — “The father of the modern fantasy pastiche is L. Sprague de Camp, who made a […]

[…] N (Black Gate) The Fantasy Roots of Fan Fiction — “The father of the modern fantasy pastiche is L. Sprague de Camp, who made a […]

> Conan would have done just fine without L. Sprague de Camp.

Docpod,

Well, it’s entirely possible that you’re right. But we’ll really never know.

What we do know is that Conan became one of the most successful and sustained literary properties of the 20th Century, and the person primarily responsible for that was de Camp.

It’s clear you’re no fan of what de Camp did with Conan (or his methods), and you’re not alone. I have no idea how many of the accusations you make are true, and this isn’t really the place for that debate anyway (it’s been hashed out several times elsewhere.) But even if everything you said is true, I don’t see how it contradicts my essential statement, which was:

> without de Camp, it’s possible the name Conan (or even Robert E. Howard) wouldn’t be nearly as well known today.

The truth of that seems fairly self-evident to me.

@John

I have nothing relevant to say, seeing as how I don’t know any of the people you talk about in this, but you asked me to comment so I figured I’d take the opportunity to remind you that you never answered my question-

Where do we keep the Stephen King books?

Dear Tabitha,

They’re in the basement, because that’s where you mother makes me keep all my horror titles (she calls them “the grody books”).

They’re alphabetical by author, but that probably won’t help you because there’s a 5-foot high pile of games and magazines in front of the second bookcase. (This is why Howard calls it the “Cave of Wonders.) Wait until I get home, and I will move the boxes and you can browse.

[…] The Fantasy Roots of Fan Fiction […]

[…] The Fantasy Roots of Fan Fiction […]