My Fantasia Festival, Days 5 to 7: Cold in July, The Fatal Encounter, and Huntresses

I’ve mentioned before that the Fantasia Festival has, logically enough, programmed what look to be their most popular movies in the big Hall Theatre. That often means unabashed genre movies — movies that aim at telling a certain kind of story a certain kind of way. A genre’s a set of conventions and a storyteller can play against those conventions or use them to get at whatever they want, as they see fit. And, especially as genres become better-known by audiences, there’s a natural inclination to mix conventions, to set genre against genre within a single story. The trick, of course, is that whichever angle you take, you should try to do it well.

I’ve mentioned before that the Fantasia Festival has, logically enough, programmed what look to be their most popular movies in the big Hall Theatre. That often means unabashed genre movies — movies that aim at telling a certain kind of story a certain kind of way. A genre’s a set of conventions and a storyteller can play against those conventions or use them to get at whatever they want, as they see fit. And, especially as genres become better-known by audiences, there’s a natural inclination to mix conventions, to set genre against genre within a single story. The trick, of course, is that whichever angle you take, you should try to do it well.

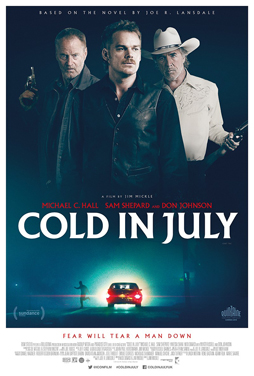

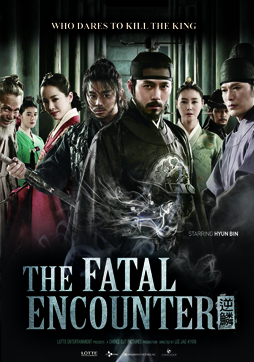

Last week from Monday (the 21st) through Wednesday, I saw three genre movies at the Hall: Cold in July, directed by Jim Mickle from a prose story by Joe R. Lansdale; The Fatal Encounter (originally Yeok-rin), a dark, violent period piece from Korean director Lee Jae-kyoo; and The Huntresses (originally Joseonminyeo Samchongsa), a much brighter period piece from Park Jae-hyun. They all aimed at a certain target, and to various degrees hit what they were aiming at. They were all working in different genres, producing different effects. But they were all intensely conscious of how genre worked.

Monday was Cold in July, scripted by Mickle and Nick Damici from Lansdale’s 1989 novella. I haven’t read it, so I can’t speak to the faithfulness of the adaptation; but the story on screen did some interesting things, starting out as a certain kind of thriller, then changing tones, then changing tone again. It begins with a man in a small town in Texas in the late 1980s, a picture-framer named Richard Dane (Michael C. Hall), who surprises an intruder in his home and accidentally shoots him dead. This leads to the dead man’s ex-con father, Ben Russell (Sam Shepard) swearing revenge. But then Dane makes a discovery that throws into question what he thinks happened, and suggests that the authorities are lying to him and Russell. A private investigator (and pig farmer) named Jim Bob Luke (played with tremendous humour by Don Johnson) enters the picture. The plot thickens. Ultimately, things resolve in a violent third act mission.

The first third or so of the movie builds a definite atmosphere of tension; violence is in the air, and you don’t know who Dane can trust and how much. That utterly changes when Luke shows up. Johnson’s charisma (aided by Mickle’s direction) is enough to shift the whole feeling of the movie. And then when mysteries have become largely clear, it’s time for gunplay; and the movie becomes almost a war story.

The first third or so of the movie builds a definite atmosphere of tension; violence is in the air, and you don’t know who Dane can trust and how much. That utterly changes when Luke shows up. Johnson’s charisma (aided by Mickle’s direction) is enough to shift the whole feeling of the movie. And then when mysteries have become largely clear, it’s time for gunplay; and the movie becomes almost a war story.

Luke mentions once that he met Russell in Korea, and that sense of old soldiers with a young recruit is I think deliberate. Dane’s an everyday small-town guy in the 80s, a man with a mullet who blasts Whitesnake on his car radio when he’s happy. But the film shows his townsfolk looking down on him slightly: “I didn’t think you had it in you,” somebody says after he kills the intruder. The gun he used was his father’s old pistol, and there’s a sense in which much of the movie swings on Dane’s sense of inadequacy. You get the feeling the movie wanted to be about masculinity, but its vision of the masculine is bound up with violence. At the end, Dane leaves his wife and child in order to take part in the climactic violence — violence in which he could easily have been killed, leaving his son without a father going forward. It’s an odd choice to make, at least given the way the film frames it.

In some ways, many of the memorable moments of the film work against the idealisation of violent masculinity. After Dane shoots the intruder, after the police come, there’s an extended sequence where he and his wife clean their home — wiping up blood, throwing out furniture, generally making their home liveable again. I thought this montage was powerful because it was both cynical and touching, wise about the consequences of violence while also showing a couple in a long-term relationship working through a stressful event. But the arc of the film moves Dane away from that kind of domesticity; Luke and Russell, older men without spouses, become role models for Dane, almost father-figures. But then again, given what we learn about Russell’s son, it’s fair to wonder about Russell’s capability as a father.

As I’ve said, the movie’s a period piece. On a basic plot level, that probably helps it, eliminating cell phones and the internet, forcing the characters to rely on themselves. It also implies a certain state of gender relations and gender roles. Mickle’s acknowledged being conscious of this, saying of the film: “I think there’s a lot of things that it says about masculinity and manhood. It needs that timeless thing. If it’s too on the nose for now, it’s not going to work. We’re in a different era. All of our movies have a timeless feel and I think this couldn’t feel like today.” It’s a fair point, but I’m not sure the film ultimately succeeds in making a meaningful statement about masculinity. As I said, it feels more like an examination of a younger man’s sense of inadequacy, and his inability to perceive the failings of two older men. But the last shots of the movie are difficult to read in that light.

As I’ve said, the movie’s a period piece. On a basic plot level, that probably helps it, eliminating cell phones and the internet, forcing the characters to rely on themselves. It also implies a certain state of gender relations and gender roles. Mickle’s acknowledged being conscious of this, saying of the film: “I think there’s a lot of things that it says about masculinity and manhood. It needs that timeless thing. If it’s too on the nose for now, it’s not going to work. We’re in a different era. All of our movies have a timeless feel and I think this couldn’t feel like today.” It’s a fair point, but I’m not sure the film ultimately succeeds in making a meaningful statement about masculinity. As I said, it feels more like an examination of a younger man’s sense of inadequacy, and his inability to perceive the failings of two older men. But the last shots of the movie are difficult to read in that light.

Then again, the movie pulls off a series of tonal shifts, keeping the audience off-balance. In some ways it’s a risky move, in that the story becomes less intense as it moves along — Dane’s family is less and less under threat, and he himself becomes involved in the larger plot more and more out of his own free choice. Add to that the greater amount of humour Luke brings, and it’s a movie that goes in the opposite emotional direction than you might expect. I tended to feel that the film was changing its main character; moving from Dane to Russell as the focus of interest, as the man who must make hard choices.

But the fact is all the characters have to make strong, interesting choices throughout the film. That’s something I expect of a Lansdale story; I’ve always found Lansdale to be as ruthless as he is imaginative. If the film’s tone is anchored by anything, it’s the echoes of Lansdale’s voice, lines of dialogue that capture a certain kind of cool Southern menace. It helps keep the film moving past loose ends in the plot — we never do uncover certain aspects of the mystery (who it is that ends up in a certain grave) or motivations (why certain law enforcement officials do what they do). Usually, a lack of clarity in plot would be a serious problem for a story like this. The fact Cold in July remains an intensely watchable movie speaks to the strength of its other elements — including the uniformly excellent lead actors.

So that was my Monday, and on Wednesday I saw two movies back-to-back. Both were set during Korea’s Joseon Dynasty, a period of several hundred years from the late fourteenth to late nineteenth century. Both promised a certain amount of action, and both delivered. But similarities ended there. If you imagine following The Lion in Winter with Errol Flynn’s Adventures of Robin Hood you’ll get an idea of what seeing these movies together was like. Sure, they’re both set in the same place and same general era. But other than that, they’re wildly different experiences.

So that was my Monday, and on Wednesday I saw two movies back-to-back. Both were set during Korea’s Joseon Dynasty, a period of several hundred years from the late fourteenth to late nineteenth century. Both promised a certain amount of action, and both delivered. But similarities ended there. If you imagine following The Lion in Winter with Errol Flynn’s Adventures of Robin Hood you’ll get an idea of what seeing these movies together was like. Sure, they’re both set in the same place and same general era. But other than that, they’re wildly different experiences.

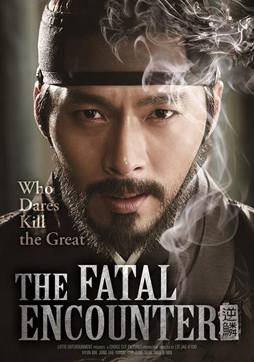

Which isn’t to say that The Fatal Encounter is anything like The Lion in Winter. It’s probably closer to a period version of Pulp Fiction — a carefully-thought-out chronology that challenges the audience, sporadic brutal violence, an extended cast of characters who interact with one another in complex ways. That said, Encounter (written by Choi Sung-hyun) is far more of an operatic genre piece, in which the conventions of its form are sometimes in conflict with the development of tragic irony.

In the 1770s young king Jeongjo (an actual historical figure, played here by Hyun Bin) is targeted for assassination by a rival political faction, who were responsible for the death of his father. The film takes place over the course of a single day, with inset flashbacks helping to clarify the action. The two main characters are the assassin who must kill the king at the end of the day (Jo Jung-suk), and Jeongjo who’s trying to uncover the plot. The king’s mother (Kim Sung-ryung) is involved in a conflict of her own with the queen dowager (Han Ji-min), the widow of Jeongjo’s grandfather. Events build during the day to a big battle scene at night, in which all the slow-burning character subplots come to a head.

I suspect that whether you like the movie or not will depend on how you deal with the complex structuring of events. The movie’s shameless about building its story around unlikely coincidences, but on the whole it does hold together. The use of flashbacks may be distracting, but as I watched it I came to appreciate the jigsaw-like nature of the film. The flashbacks gave vital information that helped build the flow of events, racing toward the climax.

I suspect that whether you like the movie or not will depend on how you deal with the complex structuring of events. The movie’s shameless about building its story around unlikely coincidences, but on the whole it does hold together. The use of flashbacks may be distracting, but as I watched it I came to appreciate the jigsaw-like nature of the film. The flashbacks gave vital information that helped build the flow of events, racing toward the climax.

It’s sumptuously shot, if heavy on shadows and blacks. The action scenes are well-choreographed, although bloody enough and stylised enough that they seem to force the movie out of its attempt at crafting a political thriller. That’s unfortunate, as the movie did seem to have some ideas on its mind. Jeongjo quotes from one of the classic Confucian texts (The Doctrine of the Mean, chapter 23) about virtue that leads to change. It’s of a piece with his character — he’s shown to be concerned with seeing to the welfare of slaves and concubines, to be concerned with fostering learning, to be an idealist who knows the classics and wants to go beyond them. But who can he trust in a royal palace consumed with plot and counter-plot?

To me, the story worked, and the build to the climax was an effective dramatic device — each scene was given a time-stamp, building the sense of the movie as a countdown to an explosion. I did think that action-movie conventions worked against the themes, and seemed out of place. Certainly there aren’t enough action scenes for the movie to work as such. But viewed as a smart period political-espionage thriller with some action elements, I felt it was quite successful.

The Huntresses was also a success, if more of a simple pleasure. Written by Kim Ga-young, Kang Cheol-gyu, and Kim Ba-da, it’s exuberant, colourful — almost startlingly so after the darkness of The Fatal Encounter — fast-paced, and inventive. It’s typically described as Charlie’s Angels in Joseon Korea (the seventeenth century, about a hundred years or so before The Fatal Encounter); its original title apparently translates directly as Joseon Trio of Beauties. Three female bounty hunters and their bumbling male agent get caught up in a struggle for military supremacy between Korea and China’s Qing Dynasty. The movie bounces giddily from sight gag to action scene to explosion (out of which heroes leap in slow motion), and almost all of it works. It’s fluff, if you like, but well-crafted fluff.

The Huntresses was also a success, if more of a simple pleasure. Written by Kim Ga-young, Kang Cheol-gyu, and Kim Ba-da, it’s exuberant, colourful — almost startlingly so after the darkness of The Fatal Encounter — fast-paced, and inventive. It’s typically described as Charlie’s Angels in Joseon Korea (the seventeenth century, about a hundred years or so before The Fatal Encounter); its original title apparently translates directly as Joseon Trio of Beauties. Three female bounty hunters and their bumbling male agent get caught up in a struggle for military supremacy between Korea and China’s Qing Dynasty. The movie bounces giddily from sight gag to action scene to explosion (out of which heroes leap in slow motion), and almost all of it works. It’s fluff, if you like, but well-crafted fluff.

It’s got martial arts, it’s got romance, it’s got some proto-steampunk elements. It’s got some fine choreography and effects shots. Its humour is on the whole clean — there’s one scene in which the three leads do a belly dance, but otherwise there’s relatively little exploitation of their sex appeal (perhaps the most tasteless bit is a scene with their male agent in brownface). The fight scenes are mostly cartoony, with fatalities avoided until the histrionic, and slightly bloody, climax. The three leads are well-defined, each with their own sub-plot.

Like the other two movies I’m written about, it blends genres, in this case comedy, action, and melodrama, and on the whole does it quite well. At the climax the melodramatic aspects seemed to slow the movie down, but by that point it’s well-earned. It may be that of all these three movies, this one is deftest at moving from tone to tone. I don’t know that it has as much on its mind as the other two, but I don’t know that it needs to. Certainly it has a lightness of touch that comes from not taking itself too seriously until and unless it absolutely must. It’s a quick, bright movie about three skilled, sympathetic, strong-willed heroines having a fun adventure. It is absolutely a genre story, and a very well-made one: it does what it does, and does it well. Can you ask for more?

(You can find links to all my Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.