Changa’s Safari: Volume 2 by Milton Davis

I read fantasy — and swords & sorcery in particular — because it’s fun. Like most middle-class Americans I lead a very safe life, which I’m very happy about, but from which I sometimes like to take a break. Occasionally I need to hear the whoosh of a sword just missing Conan’s head, to peer down into the dark alleys of Tai-tastigon from the rooftops of strange gods’ temples, to smell the fires of Granbretan’s vile sorceries. Sometimes I need to get out of my content, comfortable place and journey to places unknown and fantastic.

I read fantasy — and swords & sorcery in particular — because it’s fun. Like most middle-class Americans I lead a very safe life, which I’m very happy about, but from which I sometimes like to take a break. Occasionally I need to hear the whoosh of a sword just missing Conan’s head, to peer down into the dark alleys of Tai-tastigon from the rooftops of strange gods’ temples, to smell the fires of Granbretan’s vile sorceries. Sometimes I need to get out of my content, comfortable place and journey to places unknown and fantastic.

Milton Davis, sword & soul maven, delivers exactly that kind of trip in Changa’s Safari: Volume 2 (2012). The story of swashbuckling merchant Changa Diop traveling the 14th century Indian Ocean, it continues the adventures of Changa’s Safari: Volume 1 (2010), which was reviewed by Charles “Imaro” Saunders on Black Gate several years ago.

Once a prince of the Bakongo, Changa was sold into slavery when his father was killed by the sorceror Usenge. He was rescued from the slave-fighting pits of Mogadishu by a kindly merchant. His rescuer, Belay, taught him how to be a trader and eventually made him his heir.

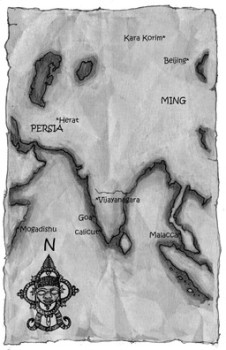

Vol. 1 tells of the arrival of a great Chinese fleet off the East Africa coast and Changa’s journey alongside it back to China with his own fleet. There he confronts — boldly and with plenty of sword flourishing and magic — all manner of things you’d hope to meet in this kind of story: evil demigoddesses, pirates, conniving courtiers, and a Mongol horde. You know, the good stuff.

Volume 2 picks up a short time after Changa and his ships have left China for home. Home is Sofala, once a prosperous port in present-day Mozambique. It’s a long way from the Straits of Malacca (where the book opens with a tremendous multi-ship battle against Sangir pirates) to Sofala, which leaves a lot of room for adventure.

The Kazuri made a dead run into the midst of the Sangir junks. Arrows and bolts whizzed by Changa’s head as he maneuvered to welcome the Sangir boarders. Angry Sangir swung from the mast ropes, falling onto the Kazuri’s deck with sewars and swords drawn. Cannons roared and the Kazuri shook, baharia and Sangir stumbling with the impact of cannon balls against wooden hulls. Chunks of wood sprayed from the broadsides of the junks flanking the dhow, but the Kazuri pushed through undamaged.

As skilled as he is, Changa’s success is not won alone. The comrades with whom he surrounds himself are each skilled and memorable in their own ways. Foremost is the blue-robed and silent swordsman known only as the Tuareg; Zakee is a young Yemeni prince rescued from a disastrous marriage; the irascible navigator Mikaili is an Ethiopian with plans to become an priest someday…just never today; and finally there is Panya, Yoruban sorceress and beloved of Changa.

Davis convincingly portrays the affection these characters have for one another and how they have come to view each other as family. As several of the major characters work to achieve their personal goals, Changa and the rest of the crew are ever ready to step in out of their loyalty and feelings of deep obligation to their brothers of the sea.

While both volumes of Changa’s Safari are billed as novels, and there is an overarching plot, they read more like fix-ups of short stories. The first story, set in Goa and Vijayanagara, pits Changa and his companions against Thuggees and an avatar of Kali. The second finds the merchants in a battle against a zombie army in San’a. In the book’s final section, Changa alone faces off against a revived mummy and ensorcelled soldiers. Each could stand quite well on its own.

Changa is a hero given to doing the right things for the right reasons, but with enough grit to keep him from being unbelievable. Even after he realizes he’s been ensnared by a woman’s magical aura, he still insists on protecting her. On the other hand, when he serves as Zakee’s advisor he is quite ready to tell him to kill his brother, not believing the brother has truly submitted following a duel.

Changa is a hero given to doing the right things for the right reasons, but with enough grit to keep him from being unbelievable. Even after he realizes he’s been ensnared by a woman’s magical aura, he still insists on protecting her. On the other hand, when he serves as Zakee’s advisor he is quite ready to tell him to kill his brother, not believing the brother has truly submitted following a duel.

The merchant is swift to act at the slightest sign of danger, which results in plenty of action. That’s something I consider a very good thing. Even in a city where he’s the alien, Changa, when confronted by a party of debt collectors, has little patience or fear:

The men marched up to Changa apparently not impressed by his size or demeanor. The smallest of the four stood before him, raising his head to look the Bakongo in the eyes.

“Stand aside,” he ordered in Arabic. “We have business with Ahmed.”

“If you have business with Ahmed then you have business with me,” Changa answered. “He is under my employ now.”

The man looked Changa up and down. He glanced back at his companions. Their expressions remained emotionless.

“Our employer is a reasonable man. Pay Ahmed’s debts and he is free to go with you.”

“I have no intention of paying his debts,” Changa answered. “Once he returns he can settle his accounts.”

“That is not acceptable!” The small man reached for his blade then screamed as Changa cut off his hand. Changa spun away from the sword swing of the closest man then threw a knife into the gut of the man behind him. The other two men stood motionless, their swords drawn, theirs faces locked in shock. The short man clutched his bleeding stump as he whimpered.

Changa’s a character who feels like he might have stepped straight off the pages of a 1970s swords & sorcery book, probably one from DAW with the yellow spine. Except Davis has something else going on that only Charles Saunders was doing back then. He’s taking S&S and transforming it into something that expands the boundaries of the genre.

Instead of using the usual faux-European settings so beloved of fantasy to this day (even ‘groundbreaking’ work like A Song of Fire and Ice doesn’t break free of those chains), Davis sets his stories in Africa and lands to the East. He uses locations that most of us don’t know too much about and creates a playground of magical wars and monster fights. His characters don’t look like the characters depicted on the typical fantasy covers. They aren’t white, for one thing, but a palette of darker colors.

doesn’t break free of those chains), Davis sets his stories in Africa and lands to the East. He uses locations that most of us don’t know too much about and creates a playground of magical wars and monster fights. His characters don’t look like the characters depicted on the typical fantasy covers. They aren’t white, for one thing, but a palette of darker colors.

As a conservative middle-class white man, many of the effects, like those of identity and empowerment, that Davis and a legion of contemporary fantasy writers are bringing to the genre don’t affect me quite the way they might if I were somebody else. On the other hand, as a reader of fantasy for forty years now, I’m bored with the same old stuff year in and year out. Milton Davis, in working to broaden the nature and appeal of heroic fiction, is also breaking down the stranglehold on the genre of Fantasyland, Inc. This is the type of book I’m constantly on the lookout for these days.

Both Changa’s Safari volumes will transport you to a world oceans away from America. The smell of spices from distant lands will fill your nostrils and the creaking of ships on the rolling sea will fill your ears. The sudden clash of steel and the whistle of cannonballs overhead will break the quiet and you’ll feel the magical forces marshalling in the distance. Milton Davis’s stories are a reminder that fantasy needn’t be dark and brooding to be good — it can be fun.

Oh, and Changa’s Safari: Volume 3 just became available as an e-book. So read the first two quickly so you can pick up the new one.

Thanks for the good words, Fletcher. The Changa’s Safari series is my favorite. I have fun writing the stories and I hope folks have fun reading them.

Between writers like you and platforms like Black Gate, the flame of swashbuckling S&S is being kept alive.