The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes: The Crimes Club

Violette Malan wrote a post about Isaac Asimov’s Black Widower mysteries. These were stories about a group of men, members of a private club, who met monthly and tried to solve a guest’s mystery.

The Black Widowers were based on a real-life group that Asimov was a member of, The Trap Door Spiders. Founded by science-fiction author Fletcher Pratt, I believe that the roots go even deeper and can be traced back to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Name That Crime – In December of 1903, six men met for lunch at the Carlton Club in London. That meal was the genesis for the formation the following year of Our Society, better known as The Crimes Club. The founding members, including Doyle, met at London’s Grand Central Hotel on July 17, 1904 for a dinner.

The Crimes Club would meet three or four times annually on a Sunday evening. After dinner, a member and/or a guest would give a talk about a celebrated crime, recent or historical, and the members would discuss and debate it, likely over drinks and cigars. Often, lawyers who had been involved in the case would provide inside information.

Doyle was pleased with the opportunity to hear what had happened to persons in the famous cases, as well as to see trial exhibits and even handle actual evidence.

Such items included strychnine pills found on convicted poisoner Dr. Thomas Neill Cream when he was arrested and bones from the right arm of the Radcliffe Highway Murderer, John Williams.

Williams’s burial site had been dug up when a water main was being laid in 1910. Club member George Sims saw a unique opportunity and grabbed the bones!

And of course, they talked about Saucy Jack: Jack the Ripper!

No crime has held such enduring interest as that of Jack the Ripper. I have nearly fifty books on the subject on my shelves and there are plenty of online resources, such as Casebook: Jack The Ripper.

In the Fall of 1888, someone murdered five prostitutes (alleged numbers vary, but I’m sticking with five) in London’s East End. The Ripper finished with the unspeakably savage killing of Mary Kelly and then disappeared.

The case was never officially solved, though it has been alleged that the killer(s) was identified and the matter covered up. There is no shortage of suspects, from the plausible (an unidentified sailor) to the silly (Alice in Wonderland author Lewis Carroll!).

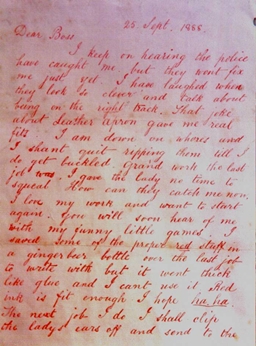

On December 2, 1892, Doyle visited Scotland Yard’s famous “Black Museum,” then the world’s leading crime museum. There, he saw a graphic photo of Mary Kelly’s corpse, and the famous “Dear Boss” letter, in which the name ‘Jack the Ripper’ first appeared. As an English mystery author, he had to be interested in the case.

In April of 1905, members of the Crime Club received a tour of various Ripper-related sites from Dr. F.G. Brown, the City of London Police Surgeon. Of course, Sir Arthur was one of the attendees. Brown himself had been at one crime scene and performed the autopsy on victim Catherine Eddowes.

One theory, popular at the time, was that the killer was a Jewish ritual slaughter man: someone who would be familiar with dissection. There had also been a message chalked on the wall near a murder site that pointed suspicion at “the Juwes.” This message was later to become a key part of the ‘Masonic Conspiracy’ angle (more on that next week).

One of the sites seen was the room where the Ripper tortured and mutilated Mary Kelly. Churton Collins said of it: “It was somber, sinister, unwholesome and depressing…”

Fragments of women’s clothes were found in the fireplace of Kelly’s rooms. This may have contributed to Conan Doyle’s own belief that the Ripper was a man who disguised himself as a woman to escape the scenes of his crimes.

Doyle also speculated that the Ripper was an American, due to the language used in the ‘Dear Boss’ letter.

The inspiration for Sherlock Holmes, Dr. Joseph Bell, is said to have studied the case, deduced the name of the murderer and supplied it to Scotland Yard. The killings stopped almost immediately. The name Bell gave them has never been publicized.

Next week, we’ll stay with Jack the Ripper by looking at 1978’s Murder By Decree, featuring a very good Holmes performance by Christopher Plummer.

IT’S ELEMENTARY – Doyle never mentioned the Ripper in any of his Holmes stories. In fact, during the time that the actual events were transpiring, Doyle had placed his great detective in Dartmoor on dog-catching duty. Sherlock Holmes was running down The Hound of the Baskervilles in the fall of 1888.

Bob Byrne founded www.SolarPons.com, the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’ and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He’s also willing to discuss Ripper books with you.

Another great piece, Bob. I love the idea of these real life crime clubs, and hadn’t heard of this one.

I’m particularly intrigued by the thought of them sitting around solving historical crimes. It reminded me of Nero Wolfe’s stand that Richard III was not the murderer of the two princes.

@Violette – The original members of the Crimes Club were: Henry Brodbibb Irving (son of legendary actor Sir Henry Irving), Arhur Lambton, James Beresford Atlay (criminal authority), Lord Albert Edward Godolphin Osborne, John Churton Collins (Birmingham Univ. English Professor), Samuel Ingleby Oddie (would help prosecute H H Crippin), A.E.W Mason, Max Pemberton (mystery author), George R. Sims (author of the “Dorcas Dene” mysteries), C.A. Pearson (publisher of ‘The Standard’ and ‘Pearson’s Weekly’), Fletcher Robinson (helped provide Doyle with the idea for The Hound of the Baskervilles), Dr. Herbert Crosse and Doyle himself.

As the creator of Sherlock Holmes, Doyle himself was asked to offer his advice regarding crimes.

He is well known for having led successful fights to free George Edalji and Oscar Slater; two men wrongly imprisoned for crimes that they did not commit.

He also argued (much less successfully and meritoriously) on behalf of Sir Roger Casement, who was executed for treason during World War I.

I did some research on Dr. Tumblety, the infamous American quack doctor and Ripper suspect, for my book Outlaw Tales of Missouri. He had a St. Louis connection. I think a good case can be made for him being the Ripper, although no suspect is supported by a truly solid case.

What do you think of Tumblety as a suspect?

@Sean – I like your comment, “although no suspect is supported by a truly solid case.” Good disclaimer that sets the basis for discussion of suspects. It’s all relative that way.

Stewart Evans’ book on Tumblety introduced me to that author’s very fine Ripper research. I think Tumblety is a viable suspect.

And that book, ‘Jack the Ripper: America’s First Serial Killer’ is absolutely worth reading.

I have three or four books by Evans and he’s a top notch Ripper researcher.

[…] went Doylean over at Black Gate this week. Doyle was a founding member of an interesting group called The Crimes Club. They could be viewed […]