Sage Stossel’s Starling

There’s a suspicion common in genre circles when a writer or creator from ‘the mainstream’ uses genre conventions or plot points. It’s sometimes a justified suspicion, as the writer unfamiliar with genre falls into cliché or loses control of their material through inexperience with the form. But sometimes something else happens: fresh eyes can find new truths. And every so often somebody approaching a genre by starting at square one can show why the classic genre material works in the first place — and even twist that material a bit to find new life for it going forward.

There’s a suspicion common in genre circles when a writer or creator from ‘the mainstream’ uses genre conventions or plot points. It’s sometimes a justified suspicion, as the writer unfamiliar with genre falls into cliché or loses control of their material through inexperience with the form. But sometimes something else happens: fresh eyes can find new truths. And every so often somebody approaching a genre by starting at square one can show why the classic genre material works in the first place — and even twist that material a bit to find new life for it going forward.

I’m prompted to this reflection by reading Sage Stossel’s graphic novel Starling, an unconventional super-hero story. Stossel readily admits that she wasn’t a super-hero fan befoe starting the book. As she says:

I happened to walk past Newbury Comics in Harvard Square, and I noticed all these superhero-related materials in the window and found myself wondering why people are so into that stuff. After all, I figured, if you really think about it, being a superhero would be kind of a logistical nightmare. And it occurred to me that there might be some humor to be mined from that.

It’s an obvious idea, and it’s not wrong — just something super-hero comics have been investigating since at least the 1960s and the early Marvel Comics. Arguably it’s something underlying a lot of early DC books, as well: the tension between two identities and trying to succeed at both without compromising either. Stossel doesn’t seem terribly aware of this background, but as it turns out, she doesn’t need to be. She’s a skilled enough storyteller that she makes her story work, with charm and humour, and say something about super-heroes and super-hero stories into the bargain. However unintentionally, Starling becomes an odd mix of classical ideals (the super-hero who is a hero, striving through the compromises of everyday life to try to do something they feel is right) and new directions.

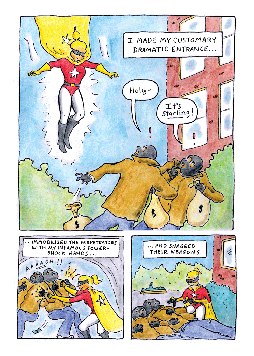

The basic idea is simple enough: Amy Sturgess is Starling, a super-strong super-hero who can fly and generate powerful electrical shocks from her hands. Loosely affiliated with a group of heroes called the Vigilante Justice Association (mentioned early on, and then never again), she fights low-level street crime; there are no powered villains, and even a gangland boss is only a minor figure in the story. The graphic novel, in fact, is mainly concerned with Amy’s attempt to balance her heroic life with her career and her family responsibilities. A scheming co-worker and a troubled little brother complicate her life at the same time as new romantic prospects arrive. Stossel weaves these elements together dextrously, using romance tropes as needed. Before the end, Amy — who begins the book in a psychiatrist’s office, gulping Xanax to help her function — will have to revisit the scene of her troubled youth and come to terms with who she is.

The basic idea is simple enough: Amy Sturgess is Starling, a super-strong super-hero who can fly and generate powerful electrical shocks from her hands. Loosely affiliated with a group of heroes called the Vigilante Justice Association (mentioned early on, and then never again), she fights low-level street crime; there are no powered villains, and even a gangland boss is only a minor figure in the story. The graphic novel, in fact, is mainly concerned with Amy’s attempt to balance her heroic life with her career and her family responsibilities. A scheming co-worker and a troubled little brother complicate her life at the same time as new romantic prospects arrive. Stossel weaves these elements together dextrously, using romance tropes as needed. Before the end, Amy — who begins the book in a psychiatrist’s office, gulping Xanax to help her function — will have to revisit the scene of her troubled youth and come to terms with who she is.

The plot is structured very well, with genuinely surprising twists. Coincidence does figure in it heavily; the world, at times, feels quite small. But it works, bringing together by the end all the different aspects of Amy’s life. There’s something very traditional in that, as the things learned in one identity provide the key to getting out of jams in the other. At the same time, however unwittingly, Stossel does new things with the old formula — in part, simply by making the main character a woman.

Stossel’s said that “I was really just looking to try to mine the humour in a superhero’s juggling act with everyday life. But afterwards, it did occur to me that it could be a good metaphor for the classic woman’s juggling act of trying to have it all.” She’s quite right. But it has also been observed (frequently) that the male super-hero of the 1950s, and to an extent even of the Marvel Age, was a weirdly effective symbol of the male work experience of that era. As a majority of North American men became office workers for the first time, the idea of the hero spending most of his time as an everyday man in an everyday suit but secretly using great power to set the world to right gained a peculiar resonance. It has also often been said that the weirdly sadistic love triangle of secret identity, love interest, and super-hero — Clark, Lois, and Superman — was a distorted and somewhat disturbing take on contemporary gender relations. What Stossel does in Starling, then, is take a form that traditionally expressed some kind of imaginative metaphor for men’s life experience — a way in which men (often unintentionally) expressed something about men’s lives to (primarily) boys — and use it in almost exactly the same way to say something about women’s life experience. It works smoothly, fluidly, and naturally.

Stossel’s said that “I was really just looking to try to mine the humour in a superhero’s juggling act with everyday life. But afterwards, it did occur to me that it could be a good metaphor for the classic woman’s juggling act of trying to have it all.” She’s quite right. But it has also been observed (frequently) that the male super-hero of the 1950s, and to an extent even of the Marvel Age, was a weirdly effective symbol of the male work experience of that era. As a majority of North American men became office workers for the first time, the idea of the hero spending most of his time as an everyday man in an everyday suit but secretly using great power to set the world to right gained a peculiar resonance. It has also often been said that the weirdly sadistic love triangle of secret identity, love interest, and super-hero — Clark, Lois, and Superman — was a distorted and somewhat disturbing take on contemporary gender relations. What Stossel does in Starling, then, is take a form that traditionally expressed some kind of imaginative metaphor for men’s life experience — a way in which men (often unintentionally) expressed something about men’s lives to (primarily) boys — and use it in almost exactly the same way to say something about women’s life experience. It works smoothly, fluidly, and naturally.

The odd thing is that it’s intended as a parody. I can see how somebody unfamiliar with the genre might think that they were undercutting the traditions of the super-hero; but in fact that element of parody ends up reinvigorating the conventions of the form. The idea of the super-hero isn’t mocked, the way it is in something like Marshal Law or the old Mad Magazine “Superduperman“. Starling is a character with powers striving to attain an ideal she’s set for herself and struggling to do right to those around her despite temptations. There’s humour in her daily life and struggles, but nothing that undercuts the story. In fact, the lightness of touch is one of the most appealing elements of the book.

It’s a lightness that extends to the art as well. Visually, the story’s unlike any super-hero comic I’ve seen. Stossel has a background as an editorial cartoonist, and is a contributing editor at The Atlantic; she’s also done two children’s books. None of that suggests that she’d be interested in the slam-bang dynamism of post-Silver Age super-hero comics, and in fact her art is much more sedate. The story’s told in small panels with frequent close-ups; captions carry much of the narrative burden, but the visuals are clear, particularly body language. The art’s relatively undetailed, so things like facial expressions are simple, but effective. Occasionally, particularly in the occasional mass brawl, the details of staging are unclear, and sometimes backgrounds get lost, but the emotional dynamics of a scene are always clear.

It’s a lightness that extends to the art as well. Visually, the story’s unlike any super-hero comic I’ve seen. Stossel has a background as an editorial cartoonist, and is a contributing editor at The Atlantic; she’s also done two children’s books. None of that suggests that she’d be interested in the slam-bang dynamism of post-Silver Age super-hero comics, and in fact her art is much more sedate. The story’s told in small panels with frequent close-ups; captions carry much of the narrative burden, but the visuals are clear, particularly body language. The art’s relatively undetailed, so things like facial expressions are simple, but effective. Occasionally, particularly in the occasional mass brawl, the details of staging are unclear, and sometimes backgrounds get lost, but the emotional dynamics of a scene are always clear.

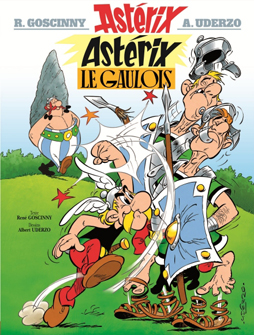

It is interesting, and deeply strange, to read a super-hero comic book that is both created in the twenty-first century and has absolutely no Kirby influence at all. Consciously or not, super-hero comics readers (and artists) are so deeply indebted to the visual vocabulary of the super-hero and super-hero storytelling that Jack Kirby created — everything from page design to the structure of fight scenes — that it’s almost shocking to see a book that goes down a different path. In fact, in terms of storytelling, the grids of small panels on each page recalls early Golden Age comics (it also recalls Albert Uderzo’s Astérix, which Stossel has said she read when young). The slightly old-fashioned feel of these page layouts works with the oddly classical sense of Starling. The restrained, simple fight scenes — it’s one of the least violent super-hero stories I’ve ever read — recall what Alan Moore once described as the “gentlemanly sock on the jaw” of Golden Age comics. Surprisingly, the lack of major fight scenes feels natural; something unusual with super-heroes, who by their nature are typically designed to fit into action-adventure stories.

Starling works as something a little different, something which hearkens back to the unpredictability of the Golden Age, before the exact use of super-hero conventions had been nailed down. Even the extensive captions create a Golden Age feel, narrating the action as it happens. As a visual, Starling herself is a classic, simple hero design, with a cape and a big star and primary colours (there’s an amusing scene where she rejects more ‘modern’ female hero costumes, vaguely recalling a scene back in the Busiek/Perez Avengers). As a character, she’s struggling with anxiety and with how to be a super-hero, but she has a kind of uncomplicated idealism underneath everything. Being a super-hero is important to her, even if she can’t articulate why.

Starling works as something a little different, something which hearkens back to the unpredictability of the Golden Age, before the exact use of super-hero conventions had been nailed down. Even the extensive captions create a Golden Age feel, narrating the action as it happens. As a visual, Starling herself is a classic, simple hero design, with a cape and a big star and primary colours (there’s an amusing scene where she rejects more ‘modern’ female hero costumes, vaguely recalling a scene back in the Busiek/Perez Avengers). As a character, she’s struggling with anxiety and with how to be a super-hero, but she has a kind of uncomplicated idealism underneath everything. Being a super-hero is important to her, even if she can’t articulate why.

In some ways, then, Starling hearkens back before Marvel and the Silver Age. I mentioned the Clark/Lois/Superman love triangle above; as a contrast, when Marvel put forward (a character some have argued was) their version of Superman in 1962, there was a love triangle — Don Blake/Jane Foster/Thor — which was abruptly resolved when Kirby, growing as an artist and creator practically by the page, jettisoned Jane Foster, forgot about Blake, and matched Thor with Sif: the super-hero and his true love adventuring together. At the same time, Kirby, who had already effectively invented the super-villain, was introducing concepts like Galactus that brought a new, cosmic dimension to the comic page. Stossel’s not interested in any of that; her take on super-heroes begins from a point before those kinds of development. What she is doing, if unintentionally, is demonstrating how much conceptual power there was in the Golden Age idea of the super-hero.

Except … she is doing it as a parody. So at the same time as she’s reconstructing the traditional idea of the white-collar middle-class hero in disguise, she’s also putting it through a kind of interrogation. What kind of comedic trials would somebody go through if they really tried to do the sorts of things a super-hero’s supposed to do? Of course the question comes from a sensibility completely unlike Kirby; but it’s question that was already answered — by Steve Ditko and Stan Lee.

Except … she is doing it as a parody. So at the same time as she’s reconstructing the traditional idea of the white-collar middle-class hero in disguise, she’s also putting it through a kind of interrogation. What kind of comedic trials would somebody go through if they really tried to do the sorts of things a super-hero’s supposed to do? Of course the question comes from a sensibility completely unlike Kirby; but it’s question that was already answered — by Steve Ditko and Stan Lee.

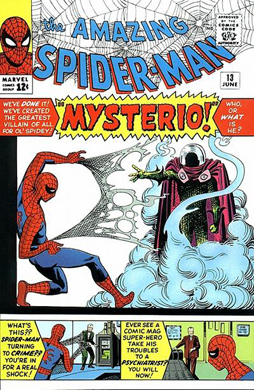

Much of her story reads like a take on early Spider-Man stories, and not just because he visited a psychiatrist early on as well (for the record: Amazing Spider-Man 13, because he was worried he was developing a split personality; actually Mysterio was impersonating him). Much of the story has to do with Amy figuring out what is right in her personal life, especially when it crosses over unexpectedly into her heroic life. A major sub-plot is the way in which she balances competing romantic interests. So, like the early Spider-Man comics, there are a number of romance elements that appear in Starling. Unlike Spider-Man, of course, Starling’s story can resolve: the romance tale can have a happy ending. Ultimately, like Spider-Man, she’s intensely aware of her own failings, and how far away she is from the image of the real, successful hero. She has to repress her anger when dealing with people at work. But at heart, she’s driven by a strong sense of responsibility.

Still, where the distinction between Amy and Peter Parker really is, what Starling really shares with the Golden Age heroes and what is very different from all the main Marvel characters, is the role of tragedy in her life. Characters like Batman and Superman had tragedies happen when they were very young; characters like Wonder Woman, the Flash, or Green Lantern never really had any tragedy in their origin stories at all. Spider-Man, on the other hand, gained his powers then brought about his father-figure’s death by his own irresponsibility. Steven Strange only became motivated to better himself because his own hedonism led him to ruin his hands in a terrible accident. Captain America (in the Silver Age) was a man out of time, grieving for his lost sidekick. Iron Man had a wound in his heart that meant he could never take off his chestplate, forever alienating him from those around him. Thor, not at first a tragic character, became caught between two worlds, forever squabbling with Odin.

There’s not much of that ongoing tragic melodrama in Starling’s background. She’s much more like a DC character in that sense; she had a troubled childhood, but her powers didn’t come about as a result of physical trauma. She is wary of getting too physically close to a man — really, a not uncommon fear among heroes — since one of the first manifestations of her electrical powers knocked out the first boy she kissed (exactly the way the first manifestation of Rogue’s super-power knocked out the first boy she kissed). But there’s none of the histrionics of early Marvel comics. Nor is there the overwrought ‘darkness’ of so many contemporary super-hero comics. There’s just the right balance of conflict and lightness of touch. Amy might find excuses to delay going into action, but she never declares “Starling no more!” and leaves her costume in a trash can.

There’s not much of that ongoing tragic melodrama in Starling’s background. She’s much more like a DC character in that sense; she had a troubled childhood, but her powers didn’t come about as a result of physical trauma. She is wary of getting too physically close to a man — really, a not uncommon fear among heroes — since one of the first manifestations of her electrical powers knocked out the first boy she kissed (exactly the way the first manifestation of Rogue’s super-power knocked out the first boy she kissed). But there’s none of the histrionics of early Marvel comics. Nor is there the overwrought ‘darkness’ of so many contemporary super-hero comics. There’s just the right balance of conflict and lightness of touch. Amy might find excuses to delay going into action, but she never declares “Starling no more!” and leaves her costume in a trash can.

Unintentionally, Starling does exactly what super-hero comics always used to do, and does it well. Most super-hero titles now are very different things than the Silver Age Marvels; their audience is different, and it’s debatable whether they can now be considered a mass medium. Super-heroes now seem to have very vestigial secret identities and tend, very often, to associate with other super-heroes. As a result, there’s something inbred about many of the current hero books. The super-heroing has become the day job. The metaphor’s shifted, and not always in the direction of greater resonance. Starling’s something of a refresher. It reads like — well, like somebody attempting a parody of super-hero comics and unintentionally creating a fine example of the form. It shows what super-hero comics once could do, and perhaps could do again, for a new audience and with a new relevance.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

[…] I mostly write about books I’ve recently enjoyed. In 2014, that included posts about surrealist Leonora Carrington’s The Hearing Trumpet, Elizabeth Hand’s Bride of Frankenstein tie-in novel Pandora’s Bride, a collection of short stories by Violet Paget AKA Vernon Lee, Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard and My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, the medieval tales in the Gesta Romanorum, Mary Gentle’s The Black Opera, Stella Gemmell’s The City, V.E. Schwab’s Vicious, Olga Slavnikova’s 2017, Jan Morris’ wonderful Hav, Phyllis Ann Karr’s Wildraith’s Last Battle, Steven Bauer’s Satyrday, the Harlan Ellison–edited shared-world anthology Medea, Pat Murphy’s three ‘Max Merriwell’ novels (There And Back Again, Wild Angel, and Adventures in Time and Space With Max Merriwell), Sylvia Townsend Warner’s debut novel Lolly Willowes, E.R. Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros and Zimiamvia trilogy, and Patricia A. McKillip’s The Changeling Sea. I also often write about comics, and last year I discussed the Steve Ditko/Wally Wood/Paul Levitz run of Stalker from the 1970s; the first volume of Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples’ Hugo-winning Saga; Alan Moore, Antony Johnston, and Facundo Percio’s Fashion Beast; and Sage Stossel’s Starling. […]