Black Hat

As I’ve mentioned a couple of times before, I entered the tabletop roleplaying world in late 1979 at the ripe old age of 10. By that point, Dungeons & Dragons – and, by extension, the hobby it spawned – were already five years old. Consequently, I can’t be numbered amongst the earliest adopters of this new form of entertainment. Even by that date, there was a lot of water under the bridge of which I was very much unaware. Moreover, unlike many of my elders in the hobby, I wasn’t a wargamer (either miniatures or hex-and-chit) and I wasn’t all that well read in the fantasy literature that inspired D&D. I was most definitely a Johnny-come-lately, loath though I would have been to admit it. In fact, it rankled me a bit. I didn’t want to be one of “the kids,” as my friends and I were often called by the teenagers and college students who frequented the hobby shops. Besides, I reasoned, how could I be a kid when my beloved Holmes boxed set proclaimed that D&D was “the original adult fantasy role-playing game?”

As I’ve mentioned a couple of times before, I entered the tabletop roleplaying world in late 1979 at the ripe old age of 10. By that point, Dungeons & Dragons – and, by extension, the hobby it spawned – were already five years old. Consequently, I can’t be numbered amongst the earliest adopters of this new form of entertainment. Even by that date, there was a lot of water under the bridge of which I was very much unaware. Moreover, unlike many of my elders in the hobby, I wasn’t a wargamer (either miniatures or hex-and-chit) and I wasn’t all that well read in the fantasy literature that inspired D&D. I was most definitely a Johnny-come-lately, loath though I would have been to admit it. In fact, it rankled me a bit. I didn’t want to be one of “the kids,” as my friends and I were often called by the teenagers and college students who frequented the hobby shops. Besides, I reasoned, how could I be a kid when my beloved Holmes boxed set proclaimed that D&D was “the original adult fantasy role-playing game?”

I eventually got my own turn to look down my nose at D&D players younger than myself when the multi-colored boxed editions written and edited by Frank Mentzer started to appear in 1983. I loudly proclaimed those “kiddie Dungeons & Dragons” and didn’t want anything to do with them – except for the Companion Rules released in 1984. I had expected the Companion Rules since 1981, when they were mentioned in David Cook’s original Expert Rulebook. Despite my disdain for these new editions, with their Larry Elmore covers and Bowdlerized presentation of D&D, I nevertheless furtively bought a copy of the Companion Rules, hoping it would live up to my expectations. It didn’t–I’m not sure there’s any way it could have – but I liked it anyway. I liked it enough that I still have my copy of it to this day and frequently pull it off the shelf to read.

I did this the other day and read its preface for the first time in many years. In it, Mentzer says the following:

This game is like a huge tree, grown from the seeds planted in 1972 and even earlier. But as a plant needs water and sun, so does a game need proper “backing” – a company to make it. As the saying goes, “for want of a nail, the war was lost”; and for want of a company, the D&D game might have been lost amidst the lean and turbulent years of the last decade. This set is therefore dedicated to an oft-neglected leader of TSR, Inc; who, with Gary Gygax, founded this company and made it grow. The D&D Companion Set is dedicated to

BRIAN BLUME

Brian Blume is not a name one hears very much in gaming circles these days. Truth be told, I’m not sure it was ever a name one heard very often. On one level, that makes sense, at least for roleplayers like me who entered the hobby in the very late ’70s. Compared to someone like Gary Gygax or Dave Arneson, Blume was a non-entity. On another level, Blume’s lack of name recognition is odd. Crack open your copy of the 1977 AD&D Monster Manual and Blume is singled out for thanks. Do the same with the 1978 Players Handbook and the 1979 Dungeon Masters Guide and he’s there as well. If you take the time to look, Blume’s name pops up a lot in TSR products. In fact, I’d say his name pops up more often than the names of other rightly lauded luminaries of the early days of gaming, like Rob Kuntz or James M. Ward. Yet almost no one mentions his name anymore or, if they do, it’s usually muttered like a curse. Why?

Brian Blume is not a name one hears very much in gaming circles these days. Truth be told, I’m not sure it was ever a name one heard very often. On one level, that makes sense, at least for roleplayers like me who entered the hobby in the very late ’70s. Compared to someone like Gary Gygax or Dave Arneson, Blume was a non-entity. On another level, Blume’s lack of name recognition is odd. Crack open your copy of the 1977 AD&D Monster Manual and Blume is singled out for thanks. Do the same with the 1978 Players Handbook and the 1979 Dungeon Masters Guide and he’s there as well. If you take the time to look, Blume’s name pops up a lot in TSR products. In fact, I’d say his name pops up more often than the names of other rightly lauded luminaries of the early days of gaming, like Rob Kuntz or James M. Ward. Yet almost no one mentions his name anymore or, if they do, it’s usually muttered like a curse. Why?

Dungeons & Dragons has been around for four decades now, long enough for a folk history of its origins and growth to have developed. Like all folk histories, it’s an admixture of truth, half-truths, and lies. In the story of D&D, Brian Blume (and, to a lesser extent, his brother Kevin) plays the role of the villain. In retrospect, this was perhaps inevitable, since Blume was a “money man.” He provided TSR (then Tactical Studies Rules) with a much-needed influx of capital with which to publish the world’s first RPG in 1974. Later, owing to financial difficulties on the part of Gary Gygax, Blume would assume ownership of the company and become its largest stockholder. Under Blume’s leadership, TSR grew and branched out in new directions, including licensed properties like Marvel superheroes. Of course, such growth often came at a cost, including some disastrous missteps. And it was Blume who paved the way, in 1985, for the ascent of Lorraine Williams to ownership of TSR (and the ouster of Gygax himself from the company he had founded).

If all or most of the aforementioned means nothing to you, that’s just as well. The struggles within TSR are murky, even to this day. I know something of what happened in those days and I don’t think anyone involved in those struggles comes across all that well – or at least no one emerges as a saint. Certainly Brian Blume made his share of mistakes, but so did Gary Gygax. The difference seems to be that, in the years since Gygax’s death, he’s been nigh-canonized. His many virtues, both as a game designer and as a man, are all that one remembers, while his own flaws and errors of judgment are forgotten. I don’t think this is inappropriate. After all, without Gary Gygax, the hobby of tabletop roleplaying as it exists today would not have come to pass and he deserves many accolades for that achievement. As that Mentzer quote above makes clear, though, so too does Brian Blume.

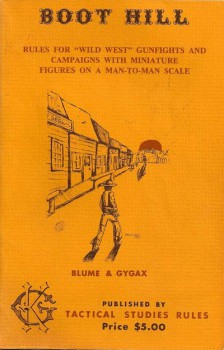

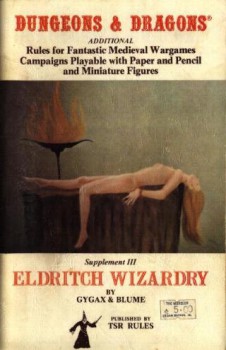

Blume was more than a mere financial backer of TSR and Dungeons & Dragons. He was, like nearly everyone involved in those early days, a player and lover of games. With Gary Gygax, he designed several games and RPG products, the first of which was Warriors of Mars, published in 1974. This was followed by Boot Hill and Panzer Warfare in 1975. Even more notably, he wrote Supplement III to original D&D, Eldritch Wizardry, which appeared in 1976. Supplement III had a lasting impact on the subsequent development of D&D, introducing such concepts as psionics, demons, and artifacts & relics, such as the dreaded Hand and Eye of Vecna. Even moreso than previous supplements, Eldritch Wizardry drew heavily on pulp fantasy for ideas and inspiration, as its cover art makes plain. Speaking only for myself, I find Supplement III a constant source of wonder and delight. It is by far and away my favorite addition to original Dungeons & Dragons. Over the course of many years, Blume also contributed articles to both Dragon magazine and its predecessor, The Strategic Review, producing material for numerous game systems. This was no stodgy “suit” without an interest in the products his company was making.

Blume was more than a mere financial backer of TSR and Dungeons & Dragons. He was, like nearly everyone involved in those early days, a player and lover of games. With Gary Gygax, he designed several games and RPG products, the first of which was Warriors of Mars, published in 1974. This was followed by Boot Hill and Panzer Warfare in 1975. Even more notably, he wrote Supplement III to original D&D, Eldritch Wizardry, which appeared in 1976. Supplement III had a lasting impact on the subsequent development of D&D, introducing such concepts as psionics, demons, and artifacts & relics, such as the dreaded Hand and Eye of Vecna. Even moreso than previous supplements, Eldritch Wizardry drew heavily on pulp fantasy for ideas and inspiration, as its cover art makes plain. Speaking only for myself, I find Supplement III a constant source of wonder and delight. It is by far and away my favorite addition to original Dungeons & Dragons. Over the course of many years, Blume also contributed articles to both Dragon magazine and its predecessor, The Strategic Review, producing material for numerous game systems. This was no stodgy “suit” without an interest in the products his company was making.

None of the foregoing is meant to assert that Brian Blume is deserving of sainthood. He made numerous bad business decisions and sometimes acted in ways that, in retrospect, don’t make much sense. I have little doubt that he was often petty and self-interested. In this respect, though, he’s no different than most human beings, including nearly everyone involved in the early days of TSR. But the truth is, if you’re a fan of D&D, you owe a lot to Brian Blume’s efforts back at the dawn of the hobby (and later as well). Far from being the Devil, as some gamers with long memories portray him, Blume was, as Frank Mentzer declared him, “an oft-neglected leader,” whose contributions ought not be forgotten.

Well said, and since the hobby has lost both Gygax and Arneson, I believe we should all take better note of Blume, and perhaps in another decade he might cast of the cloak of villainy he has worn these past twenty odd years.

[…] – and, as it turned out, only – one I ever played was TSR’s Boot Hill, co-authored by Brian Blume and Gary […]