The Clothes Make the Mage: Alan Moore’s Fashion Beast

It seems like one of those creative pairings that could only happen in comics. Odd, then, that it was originally planned to be a film.

It seems like one of those creative pairings that could only happen in comics. Odd, then, that it was originally planned to be a film.

In the mid-1980s, fashion and music impresario Malcolm McLaren called acclaimed comics writer Alan Moore. It seemed McLaren had some ideas for a film he wanted to make. The two men met and Moore was fascinated by one of McLaren’s notions: a movie that would be a modern retelling of the fairy-tale of “Beauty and the Beast,” to be set in the fashion industry — or a strange fantastical version thereof. You can see the connection: a fable about the conflict between exterior appearances and internal natures, set in a milieu that was all about appearances. Moore wrote a script titled Fashion Beast, apparently as heavily detailed as any of his comics work; in an interview with The Comics Journal a few years later, he mentioned that McLaren had observed that he’d left very little for a director to do with the film. In any event, the production never happened and the project was abandoned.

Until 2012, when Avatar press resurrected the script. With Moore’s blessing, Antony Johnston signed on to adapt the film script to comics. With art by Facundo Percio (and colours by Hernan Cabrera and lettering by Jaymes Reed), the movie script became a ten-issue limited series, now collected in a trade paperback. It’s an odd project, but the final result’s quite strong. It may not be of the same calibre as Watchmen, but it’s a very good story that seems to me to compare well with much of Moore’s other work of the period — in the range of his Swamp Thing run, say, perhaps even of V For Vendetta.

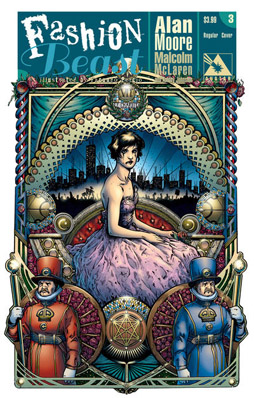

The story takes place in a nameless city at war: there are fears of a nuclear winter, with the people caught up in protests and militarism and frenetic clubbing. The city (which might be New York or might not) seems in some way to take its cue from the vast fashion house at its centre, the salon of the reclusive genius Celestine. When a boyish woman named Doll is selected as the new principal model for the house of Celestine, she becomes involved in a tense love-hate relationship with the brash young wardrobe attendant, Jonni Tare. As riots break out in the city beyond Celestine’s walls, and the war grows more pressing, the connections between Doll and Jonni and Celestine grow stranger. Everything builds to a riotous climax, and then past that, to destruction and regeneration.

The story takes place in a nameless city at war: there are fears of a nuclear winter, with the people caught up in protests and militarism and frenetic clubbing. The city (which might be New York or might not) seems in some way to take its cue from the vast fashion house at its centre, the salon of the reclusive genius Celestine. When a boyish woman named Doll is selected as the new principal model for the house of Celestine, she becomes involved in a tense love-hate relationship with the brash young wardrobe attendant, Jonni Tare. As riots break out in the city beyond Celestine’s walls, and the war grows more pressing, the connections between Doll and Jonni and Celestine grow stranger. Everything builds to a riotous climax, and then past that, to destruction and regeneration.

Tonally, the sense of apocalypse is front and centre. Throughout the book, the characters seem to be waiting for disaster and the end of all things: “Way this nuclear winter shit is shaping up, we’re all gonna end up dead!” shouts one. Celestine’s salon is a refuge from this increasingly bleak world, but it’s unstable, temporary, debated and sometimes derided by the other characters. It is unreal — but then so is the city outside its walls, where female puritans picket fashions wasting cloth that could go to the war effort, and where the military is testing “empty suits guided by computer” in irradiated war zones. So the redemption and revitalization of a single fashion house, albeit a house that at least symbolically sets the tone for society as a whole, becomes the rebirth of the world.

The centrality of the House of Celestine may be more than merely symbolic. There’s an astonishing monologue — nicely set at the exact middle of the story — in which Celestine explains to Doll how fashion, glamour, is to be identified with magic. It eerily prefigures Moore’s current fascination with the occult: “The men that wore antlers and beads knew this, dancing like dogs in the light of the first fires.” They knew that one must change or die, that fashion is evolution, that “in the image there is power!” And that:

Our affections, our vanities, these are the devil-masks that give us power, that make us loved or feared. It is our images, these lantern-ghosts that we project … these phantoms are the important things, the things that run the world.

So fashion is a stand-in for art, a symbol of power. Doll’s name is identified with a magic artifact: a voodoo doll. That connection drawn, you can’t help but notice the divine connotations of ‘Celestine,’ a name of popes and monks; also the name of an Image comic superheroine, an avenging angel created by Moore (with Rob Liefeld and Brian Denham) in 1995. And then there’s Jonathan Tare. Tare’s an obvious homonym of ‘tear,’ which in the context of clothes hints at destruction and violence. But there’s more than that going on. ‘Tares’ in the King James Bible are mentioned in one of Christ’s parables (Matthew 13:24-30). They’re weeds that symbolise demons and the wicked. But the parable ultimately implies that only God can tell the tares from good wheat, and thus that dissent should be allowed or encouraged; in fact that’s what Celestine is doing, knowing that this arrogant wiseass boy is also a talented designer. (And, of course, knowing McLaren’s connection to the book you can’t help but think of his relation to another rebellious young Johnny.)

So fashion is a stand-in for art, a symbol of power. Doll’s name is identified with a magic artifact: a voodoo doll. That connection drawn, you can’t help but notice the divine connotations of ‘Celestine,’ a name of popes and monks; also the name of an Image comic superheroine, an avenging angel created by Moore (with Rob Liefeld and Brian Denham) in 1995. And then there’s Jonathan Tare. Tare’s an obvious homonym of ‘tear,’ which in the context of clothes hints at destruction and violence. But there’s more than that going on. ‘Tares’ in the King James Bible are mentioned in one of Christ’s parables (Matthew 13:24-30). They’re weeds that symbolise demons and the wicked. But the parable ultimately implies that only God can tell the tares from good wheat, and thus that dissent should be allowed or encouraged; in fact that’s what Celestine is doing, knowing that this arrogant wiseass boy is also a talented designer. (And, of course, knowing McLaren’s connection to the book you can’t help but think of his relation to another rebellious young Johnny.)

There’s an excellent issue-by-issue review of the series at the comics news and reviews site The Beat which suggests that the story’s concerned with the maturation of its leads, following the creation and destruction and re-creation of their personalities. I think that’s one of the threads (as it were) that make up the story and give it thematic depth. But there’s more going on. There’s an examination of authority, personal and social, and the temptation to collaborate with authority; the way power works, and the way it can be misused. Conversely, the book also looks at sex as revolutionary, an idea often reflected in Moore’s work. Sex is a resolution, a way to union.

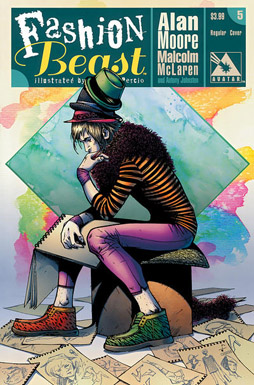

You can see other concerns of Moore’s at work in the story. There’s a questioning of militarism, for example, and an ironic look at the way in which society accepts and promotes the military. Again, sexuality’s opposed to militarism: the army in this book has a neurotic fear of sexual disease and of homosexuality within its ranks — something that would have played much differently in the 80s than it does now. There’s an implicit undermining of gender binaries: Moore notes in an introduction that one of McLaren’s ideas was “that two of the principal characters might be ‘a girl who looks like a boy who looks like a girl’ and ‘a boy who looks like like a girl who looks like a boy.’” If that play with gender is to an extent negated by the emphasis on straight sexuality in much of the book, the questioning of fashions and of the gendered emphasis of ‘glamour’ perhaps restores a sense of fluidity and unpredictability.

You can see other concerns of Moore’s at work in the story. There’s a questioning of militarism, for example, and an ironic look at the way in which society accepts and promotes the military. Again, sexuality’s opposed to militarism: the army in this book has a neurotic fear of sexual disease and of homosexuality within its ranks — something that would have played much differently in the 80s than it does now. There’s an implicit undermining of gender binaries: Moore notes in an introduction that one of McLaren’s ideas was “that two of the principal characters might be ‘a girl who looks like a boy who looks like a girl’ and ‘a boy who looks like like a girl who looks like a boy.’” If that play with gender is to an extent negated by the emphasis on straight sexuality in much of the book, the questioning of fashions and of the gendered emphasis of ‘glamour’ perhaps restores a sense of fluidity and unpredictability.

It’s interesting to read Fashion Beast as a text that was created almost thirty years ago. You can see some elements with a distinct resonance for the 1980s, elements that echo what Moore was writing about at the time. Most notably, the apocalyptic background and the fear of nuclear winter. That’s a part of the setting of V for Vendetta, and Moore’s described how that sort of paranoia played into Watchmen. But as well perhaps the sense of culture, specifically of culture effectively diffusing outward from a single core institution, follows a model closer to the 80s rather than today’s more diffuse and multi-centred Internet age. On the other hand, Jonni Tare’s exultant praise of a romanticised street scene that represents “vitality” and “real action,” and implictly opposes the formality of Celestine’s salon, smacks of William Gibson’s street finding its uses for things. So one might say that the interaction of street and salon reflected the tension of those times, rather than our more wired century.

At any rate, I think all these elements come together in one of Moore’s recurring themes: change or die. In Celestine’s words, “The point is your survival. The point is your evolution.” So the characters must change and evolve. Society changes and evolves. The more change is held back out of fear, the more violent the change will be when it comes.

At any rate, I think all these elements come together in one of Moore’s recurring themes: change or die. In Celestine’s words, “The point is your survival. The point is your evolution.” So the characters must change and evolve. Society changes and evolves. The more change is held back out of fear, the more violent the change will be when it comes.

It’s a simple idea, but Moore finds fascinating ways to complicate it. One example: Tare bitterly says early on that “We don’t have nuclear winters here in the salon. Here there’s just spring and autumn.” Spring and autumn: the seasons of new fashion lines, but also the seasons of birth and decay. Change and death, again. But also, in context, the line is Tare expressing his anger over the salon’s isolation from the outer world. The dialogue does a number of things, condensing meaning.

Still, as the plot unfolds, things become simpler again. You start to become aware that for all its interest in questioning authority, the book is ultimately about male geniuses clothing a female model. The end of the book does partially subvert that set-up, as Doll appears on the catwalk in semi-improvised garb and ultimately it’s possible to read the book as aware of her muse-like status. But there’s also a danger of the book falling into easy romanticisation of the act of destruction. If Jonni Tare is a rebel against Celestine, how much should we trust him or his assessment of Celestine’s life and work? Presumably, we’re meant to see some meaningful difference in how Tare relates to Doll — but that’s hard to see and it’s correspondingly easy to see the end of the book as a cynical acknowledgement of the fact that as one beast dies, another is born.

For the structure of the Beauty and the Beast story is always implicit in Fashion Beast. Celestine, the mad hermetic hermit, is the beast to Doll’s beauty. You can see the outline of events clearly: Doll coming to Celestine’s castle-like salon, being taken in and coddled, then returning to her home to visit, the heart-broken reaction of the beast … it’s familiar and new at the same time. Perhaps that’s appropriate in a story about the cycle of death, rebirth, and the new that becomes the old. And certainly the familiar structure is here refreshed in a number of startling ways.

For the structure of the Beauty and the Beast story is always implicit in Fashion Beast. Celestine, the mad hermetic hermit, is the beast to Doll’s beauty. You can see the outline of events clearly: Doll coming to Celestine’s castle-like salon, being taken in and coddled, then returning to her home to visit, the heart-broken reaction of the beast … it’s familiar and new at the same time. Perhaps that’s appropriate in a story about the cycle of death, rebirth, and the new that becomes the old. And certainly the familiar structure is here refreshed in a number of startling ways.

In his introduction to the book, Moore says this is “the first of my works that I’ve been able to read as if it were written by someone else, so much time having elapsed since its inception that, with everything save for the barest plot outline forgotten, much of this book seems completely new to me.” He notes the ability of the creative team to find comics equivalents for film-specific ideas in the script, and in fact the book never reads like an adaptation from one form into another. The storytelling choices, from layouts to colours to the use of visual metaphors, all feel like ideas native to comics.

Antony Johnston’s an experienced prose and comics writer who’s worked with Moore before, having adapted a number of Moore’s pieces in other media for Avatar. He also founded NinthArt.com, an online critical journal of the comics medium. So he’s got experience with thinking about the technical aspects of the comics form and how it works. Artist Facundo Percio came to comics more recently, and before Fashion Beast was probably best known for working with writer Warren Ellis on Ellis’s Anna Mercury series. Percio had a real challenge before him, designing the fashion creations of two separate geniuses; I have no eye for clothes whatsoever, but it seems to me he succeeded well enough. More importantly, perhaps, he created memorable visual designs for the characters and made them live in their facial expressions and body language.

In fact, character seems prominent in the storytelling choices of the book. Johnston and Percio aren’t afraid to take long passages to examine important character moments, or use extended reaction shots, or show emotions passing in sequence across a character’s face. The result is a distinct pace, slow without feeling overly decompressed; there’s something measured to it, a rhythm that builds in a way not unlike Watchmen. Some of this is probably a function of the story’s origin as a film script, as extended shots are divided up into separate images. Certainly, there’s frequent use of so-called ‘widescreen’ panels — comics panels with aspect ratios similar to a widescreen film. That technique in comics often feels excessively and self-consciously cinematic, and frequently slows down the pace of the story. Both pitfalls are deftly avoided here, as the page-wide panel sequences are deftly interleaved with more traditional layouts. It becomes a nicely-judged element of the overall pacing, as well as a visual motif.

In fact, character seems prominent in the storytelling choices of the book. Johnston and Percio aren’t afraid to take long passages to examine important character moments, or use extended reaction shots, or show emotions passing in sequence across a character’s face. The result is a distinct pace, slow without feeling overly decompressed; there’s something measured to it, a rhythm that builds in a way not unlike Watchmen. Some of this is probably a function of the story’s origin as a film script, as extended shots are divided up into separate images. Certainly, there’s frequent use of so-called ‘widescreen’ panels — comics panels with aspect ratios similar to a widescreen film. That technique in comics often feels excessively and self-consciously cinematic, and frequently slows down the pace of the story. Both pitfalls are deftly avoided here, as the page-wide panel sequences are deftly interleaved with more traditional layouts. It becomes a nicely-judged element of the overall pacing, as well as a visual motif.

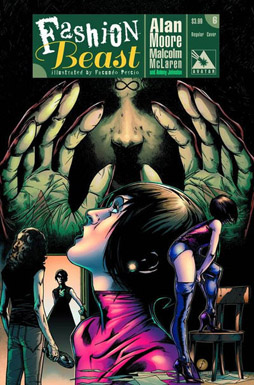

On the whole, the book is extremely clever in its visual identity. Celestine’s obsession with the image, with surfaces, translates nicely into a general play with images. Accordingly, many things in the book are seen in mirrors, or through windows, or from the other side of a glass. The ambiguous gender presentation of Doll and Jonni are part of a broader questioning of appearances and surfaces — just as the human body itself becomes commoditised, as models sometimes are mannequins and sometimes are not.

It has all the usual intelligence of an Alan Moore comic, and I can’t help but feel that this project’s been under-discussed. It’s a genuine lost work of Moore’s from the 80s that holds up to all but the best of his other comics. It’s creative, complex, and highly original. There’s a whole world created in this comic, and a distinct, unique tone. It’s a fairy tale, a political statement, a metaphor in action. I suspect it would have had a bigger impact if it had come out twenty or thirty years ago; but the comics field is bigger now, and if it’s still impossible for a work like this to be entirely overlooked, there are more creators now with more projects to read.

It has all the usual intelligence of an Alan Moore comic, and I can’t help but feel that this project’s been under-discussed. It’s a genuine lost work of Moore’s from the 80s that holds up to all but the best of his other comics. It’s creative, complex, and highly original. There’s a whole world created in this comic, and a distinct, unique tone. It’s a fairy tale, a political statement, a metaphor in action. I suspect it would have had a bigger impact if it had come out twenty or thirty years ago; but the comics field is bigger now, and if it’s still impossible for a work like this to be entirely overlooked, there are more creators now with more projects to read.

Oddly, in retrospect it seems like Moore and McLaren were slightly in advance of the zeitgeist with their idea of a project based on “Beauty and the Beast.” In 1987, a TV show began airing, very loosely based on the fable. In 1991, Disney came out with its version. Perhaps all these versions, like Fashion Beast, are to some extent in the shadow of Jean Cocteau’s 1946 masterpiece; I think Moore’s story is perhaps the most comparable in its originality and sense of wonder. It would have been fascinating to see as a film. It’s certainly highly rewarding and entrancing as a comic.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

A great review as always, Matthew.

Avatar did something similar with Moore’s prose story The Courtyard (featured in the Lovecraftian anthology The Starry Wisdom), adapting it to comic form with his blessing (he served as “consulting editor”). Moore later scripted a somewhat controversial sequel in comic form, Neonomicon, which was also released by Avatar.

Yes, Matthew — thanks for the head’s up on this! I had no idea it existed.

(And for the record, I consider V FOR VENDETTA his finest achievement!) 🙂

Thanks for the kind words!

Golgonooza: Yep, The Courtyard was another one of the pieces adapted by Johnston. I’ve got the trade collecting it and Neonomicon. I actually preferred The Courtyard, oddly enough.

John: You know, there’s a lot of people who feel the same way (about V). I can see the point, but I’m a From Hell man myself.

[…] Vaughan and Fiona Staples’ Hugo-winning Saga; Alan Moore, Antony Johnston, and Facundo Percio’s Fashion Beast; and Sage Stossel’s […]