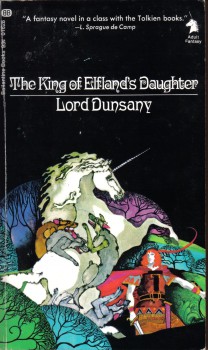

The Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series: The King of Elfland’s Daughter by Lord Dunsany

The King of Elfland’s Daughter

The King of Elfland’s Daughter

Lord Dunsany

Ballantine Books (242 pages, June 1969, $0.95)

Cover art by Bob Pepper

The second volume Lin Carter chose for the Adult Fantasy line was Lord Dunsany’s The King of Elfland’s Daughter. In my opinion, it is it far superior to Fletcher Pratt’s The Blue Star.

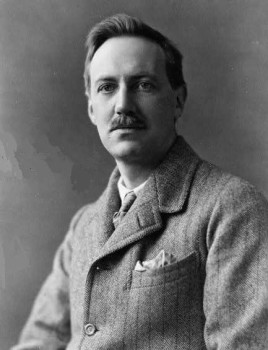

The “Lord” in the author’s byline isn’t an affectation. Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett was the 18th Baron Dunsany (1878-1957). He was a tall, lean man. His accomplishments could put most people to shame. Soldier, Member of Parliament, author, poet, playwright, chess champion, hunter, and sportsman.

Dunsany began his writing career with short fiction, set mostly in imaginary lands and much of it slight in terms of plot and character. These tales greatly influenced H. P. Lovecraft, who wrote in this vein until moving on to develop the Cthulhu mythos.

Dunsany’s later series about Jorkens concerns a man who tells tall tales in a bar for drinks. These stories were the precursors of and influences on Arthur C. Clarke’s White Hart, L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt’s Gavagan’s Bar, and Sterling E. Lanier’s Brigadier Ffellowes. A further discussion of Dunsany’s influence can be found here.

Dunsany turned to writing novels after publishing a number of short fiction collections. Among his novels, many consider The King of Elfland’s Daughter to be his finest. Lin Carter gives a brief introduction, not only discussing this particular work,but Dunsany’s work in general.

Set in the kingdom of Erl, the story opens with a parliament of craftsmen making an unusual request of the king. They want to be ruled over by a monarch who is “a magic lord.” He grants their request, but tells his son Alveric that it is not from wisdom that they make this request. And indeed, the parliament will come to deeply regret their request before the book’s final page is turned.

In order to have a magic lord, someone of magic blood must marry into the royal line. Alveric visits a witch who lives on the heights above the valley. Following her instructions, he gathers lightning bolts from under her cabbages. With them she makes a magic sword.

Alveric then heads towards Elfland. While there, he meets the King’s daughter, Lirazel, and convinces her to return with him. Avleric has to slay the King’s champions with his sword so they can escape.

Upon his return, Alveric learns that ten years have passed in Erl, although he was only gone a couple of days by his reckoning. He and Lirazel marry and have a son, Orion. They enlist the witch who made his sword to be his nurse. Although she loves Alveric, Lirazel is never able to make the transition to the lands of men, called by Dunsany “the fields we know”.

The King of Elfland, meanwhile, is not pleased. He summons a troll and sends him with a rune to give to Lirazel. This isn’t your Tolkien troll that will turn to stone when exposed to sunlight. Rather, he’s more of a free spirited, simple-minded boy. The troll delivers the rune, but rather than reading it, Lirazel puts it away.

Not long afterwards, she has a spat with Alveric and reads it. Immediately, a wind blows her back to Elfland. The borders of Elfland roll up and withdraw from near the fields we know, leaving a vast wasteland.

Consumed by grief,Alveric gathers a small band of misfits, dreamers, and madmen and goes on a quest to find Lirazel. Orion, like his namesake, grows up to become a hunter. It’s at this point that Dunsany’s love of hunting and the outdoors shows. The chapters devoted to Orion hunting are among the most detailed in the book.

At first, Orion hunts stags, but then he catches sight of a unicorn which has wandered over the border from Elfland. Unicorns become Orion’s preferred prey and he becomes consumed with hunting them. The lengths to which he goes in hunting unicorns will bring more magic to Erl than the parliament ever dreamed.

All these threads are brought together, but I’ll let you read the book to find out how. I’d like discuss some things in general about this novel.

First, Dunsany’s prose, which has a distinct style all its own. But it definitely isn’t written in a style that is common today. It’s an older, almost archaic type of writing. I suspect most modern readers would find it not to their liking.

And that’s a shame, because it’s quite beautiful and I found it easy to read. The prose in The Blue Star is in a style that, while also old fashioned, isn’t nearly as out of date as The King of Elfland’s Daughter. Yet I found the latter much more enjoyable. Dunsany’s prose has a poetry and a lyricism to it that Pratt’s is sorely lacking. Dunsany was a joy to read at times. Too often Pratt felt like work.

Here’s an example, where the troll who is bringing the rune to Lirazel is chased by a dog:

The troll began at once to rise and dip over the buttercups as though he had almost borrowed its speed from the swallow and were riding the lower air. Such speed was new to the dog, and he went in a long curve after the troll, leaning over as he went, his mouth open and silent, the wind rippling all the way from his nose to his tail in one wavy current. The curve was made by the dog’s baffled hopes to catch the troll as he slanted across. Soon he was straight behind; and the troll toyed with speed; breathing the flowery air in long fresh draughts above the tops of the buttercups. He thought no more of the dog, but he did not cease in the flight that the dog had caused, because of the joy of the speed.

Or this one where Orion is hunting a unicorn:

In that first rush the hounds drew far ahead of Orion, and this enabled him to head the unicorn off whenever it tried to turn to the magical land; and at such turnings he came near his hounds again. And the third time that Orion turned the unicorn it galloped straight away, and so continued over the fields of men. The cry of the hounds went through the calm of the evening like a long ripple across a sleeping lake following the unseen way of some strange diver. In that straight gallop the unicorn gained so much on the hounds that soon Orion only saw him far off, a white spot moving along a slope in the gloaming. Then it reached the top of a valley and passed from view.

I realize that I may be in the minority here. Most modern readers, especially those whose reading has been limited mainly to works published in the last few decades, will find Dunsany more work than they’re used to.

The only quibble I have with Dunsany was that he tended to use the phrase “the fields we know” a bit overmuch. I should mention that he also occasionally broke authorial voice and directly spoke to the reader. While this didn’t really bother me, I know it will annoy some people.

The only quibble I have with Dunsany was that he tended to use the phrase “the fields we know” a bit overmuch. I should mention that he also occasionally broke authorial voice and directly spoke to the reader. While this didn’t really bother me, I know it will annoy some people.

The King of Elfland’s Daughter isn’t sword and sorcery, but there are things in it, such as the sword forged from lightning bolts, that will appeal to S&S readers. Dunsany blends several diverse elements in the book, creating something that doesn’t really fall into any of the subgenres in the field today. There are elements of fairy tales, quests, and tragedy in the book. In my opinion, the sum is greater than the whole of its parts.

Overall, I found The King of Elfland’s Daughter highly enjoyable. This is one I heartily recommend, with the caveat that it probably won’t be a style of writing you’re used to. Also, don’t read it right before bed. Dunsany takes his time telling the stories, describing things. While the book never drags, it doesn’t race ahead with the breakneck pace of, say, Robert E. Howard.

There are two additional novels and three short story collections by Dunsany in the Adult Fantasy series. My general rule of thumb is one title per author in this series, at least until I’ve covered a number of the authors. After reading the King of Elfland’s Daughter, I’m certainly interested in reading them at some point.

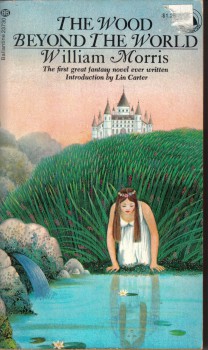

The next book in the series is The Wood Beyond the World by William Morris. I tried Morris about 10 years ago. He’s going to be work. I don’t guarantee I’ll finish it, but I’ll give it my best. If I don’t make to the end, I’ll at least publicly acknowledge my failure and tell you why.

Dunsany is my all time favorite.

IMO he did more than a “Trilogy” in a few of his short stories.

Lovecraft was a wild ‘fanboy’ for him. If you put it in modern terms he’d be a “Star Wars” fan who Mr Lucas or one of his stars like Hamill, Ford, etc. noticed was at EVERY convention in several separate states on the SAME tour… And a lot of Lovecraft’s work was trying to imitate Dunsany, most notably “The Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath” though of course with Lovecraft’s darker style.

Dunsany really shines with a lot of his short stories. They are all in the Public domain now, with a few exceptions, but I reccomend “The Sword of Welleran” and other stories!

http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Sword_of_Welleran_and_Other_Stories

Yeah! I was wondering when the next of these posts was coming. Glad to see you’re continuing on with the Ballantine series.

I agree with you that most readers today probably will not have the patience for Dunsany. I was just listening to a podcast the other night where a current author was commenting that he could never finish H. P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness because he thought the writing was poor (!).

If a current WRITER in the field can’t stomach what is considered by many to be Lovecraft’s masterpiece (and made in his post-Dunsany era), I don’t see how Dunsany is going to make a comeback anytime soon.

Nevertheless, perhaps a lone voice in the wilderness like yourself will keep a memory of Dunsany alive and perhaps just a few people interested in returning to one of the greatest prose writers to have ever graced the genre of fantasy.

One optimistic thought though, a collection of Dunsany’s work was released by Penguin a couple of years ago. Perhaps he’s being read wider than I might think.

Look forward to your Morris post!

Dunsany is fantastic, his prose poetic and haunting. I’ve read King of Elfland’s Daughter, and there are wonderful scenes, but I prefer his short fiction — his Book of Wonder holds a place of honor on my shelf.

I agree that his style is probably going to bar him from a “comeback” anytime soon, other than with diehard fans of the genre (although he is not so impenetrable to today’s mass-market audience as William Hope Hodgson or E.R. Eddison or even Mervyn Peake, three more of the all-time greats).

I’d say the Dunsany of our generation is Neil Gaiman. He is telling the sorts of tales Dunsany told, in the modern vernacular and in contemporary settings. The style is leagues different, but the substance is quite kindred — they draw from the same pools of wonder.

Looking forward to how you get along with Morris — I confess I started that book but never finished it.

Another thumbs-up for Dunsany the short story writer, although I did like King of Elfland’s Daughter well enough.

I’ve made it through Morris but he can be a bit of a tough go. For me, though, the worst in the BAF was probably Shaving of Shagpat — that was more of a struggle than Morris, Hodgson, Peake and Eddison combined.

I’ve read The Wood Beyond the World three times since a first reading in the early 1970s. The last time, not all that long ago, I read it in two days. It is probably a good idea to try to read Morris in sizeable amounts so that you have time to adjust to his style.

My favorite work by Morris — not that I have read them all — might be his Icelandic Journals.

Have read The King of Elfland’s Daughter twice, but that second reading was many, many years ago, so thank you for a nudge towards trying it again.

A true masterpiece. Anyone who appreciates poetry and poetic language will have no trouble with Dunsany’s lyrical style. Anyone who only reads “modern language” works is to be pitied.

“Anyone who only reads “modern language” works is to be pitied.”

Hear hear Mr. Fultz. Well said.

Thanks for the kind words, everyone.

James, I apologize for the delay. My wife had surgery on her rotator cuff a few weeks ago. I’m picking up most of her household chores plus playing chauffeur until the doctor clears her to drive. It’s thrown me a bit behind.

Dunsany seems to usually have something in print from what I’ve observed.

Nick, I’ve seen the comparison between Gaiman and Dunsany several times. It’s been long enough since I read Gaiman that I need to do a re-read.

Joe, I’ll be reviewing at least one of the Dunsany short story collections from BAF. The Shaving of Shagpat is on the list as well, so thanks for the heads-up.

Major, I agree about Morris in sizeable amounts and getting used to the style. I’m a little over halfway through the book and although it’s work, it’s gotten easier as I’ve gone along.

John, you’re absolutely correct.

Picked it up several years ago in a used book store. Last year it went to a library rummage sale. I never did read it (although my wife did, so not a total loss). The only reason I bought it is because I enjoy the album based on the novel. Some great songs in there.

I love Dunsany’s prose, and have read and re-read various of his short stories over the years. I’ve yet to try the three novels Ballantine printed, although they’re sitting on my shelves. I’ll get around to them some day.

I, too, pity a reader so modern that he or she can’t be swept up into the prose. Archaic, yes, but it flows and moves and it’s pretty easy to get the hang of. Unlike, say, Morris, whose work just seemed turgid.

I think The King of Elfland’s Daughter is one of the greatest fantasy novels I’ve ever read – I especially love its ambiguity. As for the language, it’s one of the book’s glories, and it was archaic and outdated when Dunsany wrote it – it was a consciously chosen artifice, selected and honed for a particular purpose. (As was Pratt’s language in The Blue Star – sorry to disagree, but that’s a great fantasy! Lyricism just wouldn’t have suited its realistic – if not cynical – view of national and sexual politics.)

Jeff, There’s an album? Please, tell me more.

Howard, I’m finding Morris and Dunsany are very different stylists. More on this in the next installment.

emcgargle, no need to apologize for disagreeing. Lively discussion about differences in opinion beats an echo chamber any day. And you’re right. Dunsany’s prose was archaic when he wrote it. Just shows what a great writer can accomplish when he sets out to blaze his own trail.

Yes Lord Stehman, what album dost thou speak of?

http://www.amazon.com/The-King-Of-Elfland%60s-Daughter/dp/B004NJ30YM/ref=sr_1_4?ie=UTF8&qid=1391710701&sr=8-4&keywords=king+of+elflands+daughter, I’m guessing — concept album from members of Steeleye Span with narration by Christopher Lee(!). Thanks for mentioning this — reminded me I needed to order it … 🙂

[…] Adult Fantasy series, The King of Elfland’s Daughter by Lord Dunsany is up on Black Gate. You can find it here. If you haven’t read it, check it out and join the discussion. There are some great […]

I don’t have time to explain, so I’ll let Wikipedia do the talking. Search for “The King of Elfland’s Daughter (album)”.

/wanders off singing “Rune singer, doom bringer, be my light through the night.

Death dealer, soul stealer, be my friend to the end.”

Oh, and of course there are samples on youtube.

Jeff’s right! Appears to be from a pair of former Steeleye Span members. Definitely based on the book.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_King_of_Elfland's_Daughter_(album)

Oh my god I must have that album!

Just did a quick check on eBay: looks like it was never released on CD, but you can get an LP copy for around fifteen bucks.

I have the CD. It’s currently $25 through Amazon sellers.

I liked what I found online about it last night. Thanks for the tip, Jeff. Much appreciated. I should note, though, that there appear to be other songs with the title “The King of Elfland’s Daughter” that aren’t related to Dunsany.

I, too, admire Lord Dunsany’s short fiction. I’ve read The King of Elfland’s Daughter (which I like very much) and The Charwoman’s Shadow (less to my taste) but I personally think he was at the peak of his powers when he wrote his shorter tales, e.g., The Gods of Pegana:

archive.org/details/godsofpeganawith00dunsuoft

“The Fortress Unvanquishable Save for Sacnoth” and “The Sword of Welleran” also come to mind. I have an old Dover collection with wonderful weird illustrations by Sidney Sime, some of which can be seen in the digitized book at the above link.

Personally, I think the only way to read The Wood Beyond the World is through a facsimile of the original Kelmscott Press edition. 🙂

Raphael, I’ll look at some of Dunsany’s short fiction later in this series. Kelscott Press was Morris’ press, wasn’t it? I finished The Wood Beyond the World last night. It was both more and less than I expected. Stay tuned for details.

[…] Lin Carter and the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series The Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series: The Blue Star by Fletcher Pratt The Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series: The King of Elfland’s Daughter by Lord Dunsany […]

[…] His most prestigious work was the creation of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series (being reviewed one volume at a time here on Black Gate by Keith West). It resurrected many of the forebears of genre […]

[…] The Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series: The King of Elfland’s Daughter by Lord Dunsany […]

[…] Carter and the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series The Blue Star by Fletcher Pratt The King of Elfland’s Daughter by Lord Dunsany The Wood Beyond the World by William […]

[…] The Black Gate — “The King of Elfland’s Daughter isn’t sword and sorcery, but there are things in it, such as the sword forged from lightning bolts, that will appeal to S&S readers. Dunsany blends several diverse elements in the book, creating something that doesn’t really fall into any of the subgenres in the field today. There are elements of fairy tales, quests, and tragedy in the book. In my opinion, the sum is greater than the whole of its parts. Overall, I found The King of Elfland’s Daughter highly enjoyable. This is one I heartily recommend, with the caveat that it probably won’t be a style of writing you’re used to. Also, don’t read it right before bed. Dunsany takes his time telling the stories, describing things. While the book never drags, it doesn’t race ahead with the breakneck pace of, say, Robert E. Howard.” […]

[…] He did write a few novels, with The King of Elfland’s Daughter being the most highly regarded. I certainly liked it a lot. […]