Skyfall: In Which a Pulp Hero Meets the 21st Century

Let me offend as many readers as possible right at the start by stating that Daniel Craig is the best James Bond the screen has yet known. The man is equal parts chiseled granite and lithe predator; he has charm, but he withholds it whenever possible, forcing us to catch it on the sly, as if we’re at a peepshow. Nobody in movies today looks better in a suit.

Let me offend as many readers as possible right at the start by stating that Daniel Craig is the best James Bond the screen has yet known. The man is equal parts chiseled granite and lithe predator; he has charm, but he withholds it whenever possible, forcing us to catch it on the sly, as if we’re at a peepshow. Nobody in movies today looks better in a suit.

Yes, Sean Connery was great, but the role of Bond requires a greater world-weariness than Connery, at least in his nineteen-sixties roles, could bring. Roger Moore brought out 007’s upper-crust prep school tastes, but he was never believably dangerous; he actually needed Q’s endless gimmicks to survive, as Craig surely does not. The various Bond inhabitors since have filled the shoes without fleshing out the man. Only Craig does justice to the flinty, ruthless public servant that Ian Fleming originally envisioned, without reducing the character to a dusty fifties history text: Cold War Tactics 101, With Style. Daniel Craig makes 007 both contemporary and relevant.

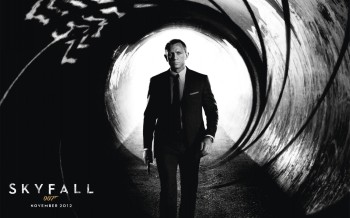

Skyfall (2013) opens with a shot of an approaching figure, out-of-focus, stalking down a dim corridor. When the figure gets close enough, the image locks on at last: it’s Bond, of course, weapon in hand, but the initial blurriness is central to the film. Skyfall presents James Bond between epochs, uncertain of his exact identity and purpose. Is he still a tool of the Cold War establishment, of traditional spy vs. spy operations, or does the world now require him to be something new? To be (as he is in the extraordinary credits sequence) reborn?

Thanks to the inherent menace of questions such as these, Skyfall is the most satisfying Bond film in decades — possibly since From Russia With Love. Skyfall tweaks the standard-issue plot in which a maniacal madman with infinite resources threatens all England, if not the world. Yes, there’s still a maniacal madman, but he’s looking inward, not out, and his sights are fixed on MI-6, and M in particular. Bond just happens to be in his way.

Skyfall offers the case of a trained attack dog turning on its master, and as such, the conflict is internal, internal to both MI-6 and Bond himself. That so many of the set-pieces and chases take place in tunnels is no accident; this film was designed, from the ground up, to swallow its own tail, and the result is the 007 equivalent of a dungeon crawl.

Skyfall offers the case of a trained attack dog turning on its master, and as such, the conflict is internal, internal to both MI-6 and Bond himself. That so many of the set-pieces and chases take place in tunnels is no accident; this film was designed, from the ground up, to swallow its own tail, and the result is the 007 equivalent of a dungeon crawl.

Serpents aside, director Sam Mendes brings an essential gravitas to his Skyfall work. Mendes’s moody offices, rain-soaked vistas, and busy, nose-to-the-grindstone crowds nearly pave over the occasional horse pill the plot requires of its viewers.

Best of all, Mendes seems genuinely interested in the relevance of the British Secret Service (and, by extension, its CIA counterpart). As M (“Mum”) sits accused by a scathing MP of being a political liability and a functional dinosaur, Mendes and his screenwriters take the time to let the scene play out — to even allow M, in her defense, to read a snippet of Alfred Lord Tennyson’s “Ulysses”:

Though much is taken, much abides; and though

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven; that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

“Ulysses” focuses on Odysseus and the Homeric epics, but such language could also tilt toward subjects Arthurian. Dipping into such fatalistic material suggests that Bond himself has matured far beyond the high-end pulps from which Ian Fleming began. Bond now merits allusions to the historical greats (including a Turner oil painting); the man carries historical heft. No wonder, then, that the film asks repeatedly whether it’s best to move with the times, or to rely on what one already knows. Thus it’s written in the stars that Kincaid the arthritic gamekeeper (Albert Finney) will hoard the film’s finest lines. “Sometimes the old ways are best,” he opines, and sure enough, Bond triumphs not with a gun, but with a knife.

And what of Bond the character? Can he survive a world in which poetry might be a reasonable weapon with which to beat back anger, malice, and lunacy? What I remember best about the Fleming novels, all of which I read between the ages of thirteen and sixteen, is Bond’s proclivity to take cold showers (ugh), and the mechanistic predictability by which any woman he slept with in the early going would soon meet a cruel, nasty demise. (The movies, of course, reveled in exactly the same, minus the cold showers.) And then there was Bond’s evident weariness, the enervation that left him spent at each book’s end, and ever the more so as the series ground on until, at the close of You Only Live Twice, Bond gives up entirely. Taxed beyond all reason, he essentially allows himself to lose his mind. After losing his wife only one book before –and damn, did that scene ever jolt this teen reader — he simply had nothing left to give.

And what of Bond the character? Can he survive a world in which poetry might be a reasonable weapon with which to beat back anger, malice, and lunacy? What I remember best about the Fleming novels, all of which I read between the ages of thirteen and sixteen, is Bond’s proclivity to take cold showers (ugh), and the mechanistic predictability by which any woman he slept with in the early going would soon meet a cruel, nasty demise. (The movies, of course, reveled in exactly the same, minus the cold showers.) And then there was Bond’s evident weariness, the enervation that left him spent at each book’s end, and ever the more so as the series ground on until, at the close of You Only Live Twice, Bond gives up entirely. Taxed beyond all reason, he essentially allows himself to lose his mind. After losing his wife only one book before –and damn, did that scene ever jolt this teen reader — he simply had nothing left to give.

A stoic ronin, that 007. A lethal weapon at the beck and call of others, one who might at first glance be mistaken for what western settlers in the U.S. used to call a “hired gun.” Bond, however, is not as smoothly analogous to gunslingers and the sword-bearing heroes of medieval tales (not to mention D&D games) from ages past as it first appears. Those other figures were often true mercenaries; they hired themselves out to make a living, then tried to do their best to make honorable choices along the way. They were their own masters (and in this they seem to share many characteristics with the wandering Samurai of Japan), but the gunslinger and the barbarian (read: Conan or Fafhrd) clung to a difficult, anarchic code, one that promoted the skills and wisdom of the loner over that of society at large. James Bond is more a direct descendant of proper knights, or perhaps Dumas’ version of a musketeer, for he serves the crown, the government. James Bond is the blunt tool by which civilized western society maintains its primacy, its safety, and its hegemony.

To his enemies — which is to say the enemies of Great Britain — Bond is closest kin to Elric of Melnibone, a grim reaper guaranteed to leave wreckage, chaos, and death in his wake. Like 007, the Prince with the Black Sword is brooding but slick; both have epicurean tastes and a flair for presentation. Both understand their own doom, but soldier on regardless.

There are differences, of course, and I don’t mean albinism. Bond works for the establishment; Elric, at least at the outset, is the establishment.

Skyfall illustrates in dramatic terms a very real political discussion that now takes place daily in the corridors of established power worldwide, and that is how to define and end what has come to be called “the war on terror.” Judi Dench’s M insists that the world has become more dangerous under her watch, because the enemy now lurks in shadow. No longer do we have the comfort of a clearly defined boogeyman such as the Soviet Union, or Ho Chi Minh. Now we enjoy the attentions of Al Queda — wherever and whoever they are.

Skyfall illustrates in dramatic terms a very real political discussion that now takes place daily in the corridors of established power worldwide, and that is how to define and end what has come to be called “the war on terror.” Judi Dench’s M insists that the world has become more dangerous under her watch, because the enemy now lurks in shadow. No longer do we have the comfort of a clearly defined boogeyman such as the Soviet Union, or Ho Chi Minh. Now we enjoy the attentions of Al Queda — wherever and whoever they are.

But traditional wars have limits, and “things get back to normal” when they’re over, as all wars, throughout history up until now, have done. What Skyfall suggests (but doesn’t fully address, since Hollywood still believes that gunplay is preferable to cogent thought) is that the war on terror will never end, and that we shall always need a rough-and-ready killer at our disposal. It also suggests that the rest of us shouldn’t worry, because said killer will be well-dressed, attend to his cuff-links, and have the fastidious tastes of the cultural elites: his martinis will always be shaken, never stirred.

Skyfall wants to talk about what Stanley Kubrick (and Arthur C. Clarke) covered so well in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Forget about that story’s space segments. Begin, instead, at the beginning, where two rival tribes of apes battle over water rights at the local river. Consider the problem: there is only one river. Resources are limited. What would Highlander, another wise-despite-itself pulp vehicle, have to say about this situation? Answer: “There can be only one.”

Skyfall wants to talk about what Stanley Kubrick (and Arthur C. Clarke) covered so well in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Forget about that story’s space segments. Begin, instead, at the beginning, where two rival tribes of apes battle over water rights at the local river. Consider the problem: there is only one river. Resources are limited. What would Highlander, another wise-despite-itself pulp vehicle, have to say about this situation? Answer: “There can be only one.”

C.S. Lewis, writing in Prince Caspian, said much the same. When young Lucy, wandering lost in the woods, becomes thirsty, she finds a stream, but she does not dare take a drink, for the water is guarded by a massive lion (Aslan). When Lucy timidly asks the lion if there is another stream she might drink from, Aslan calmly tells her no, there is only one stream.

Metaphors and British lion-gods aside, the political reality — our earthbound reality — seems clear. For so long as we have limited resources, and for so long as those resources are distributed unequally across the globe, the war on terror stands every chance of continuing indefinitely.

Fortunately our protector, James Bond, is immortal. Unlike, say, Dr. Who, not one of the Bond films makes any reference to 007’s agelessness, or his regular changes in stature, build, and height. No matter, since James Bond isn’t strictly human, not any more. He’s an avatar we summon as needed, a vengeful wraith from some fell witchy cauldron. Yes, Daniel Craig will eventually grow too old for the part, but the franchise will not die. Humanity likes to be reassured, and the fairy tale of 007 is too good a bedtime story to be discarded for something as trivial as the age of an actor.

Fortunately our protector, James Bond, is immortal. Unlike, say, Dr. Who, not one of the Bond films makes any reference to 007’s agelessness, or his regular changes in stature, build, and height. No matter, since James Bond isn’t strictly human, not any more. He’s an avatar we summon as needed, a vengeful wraith from some fell witchy cauldron. Yes, Daniel Craig will eventually grow too old for the part, but the franchise will not die. Humanity likes to be reassured, and the fairy tale of 007 is too good a bedtime story to be discarded for something as trivial as the age of an actor.

So it is that 007 will continue to enjoy his place in the Cineplex, and when he makes his appearances, we will cheer our defenders, hiss at our enemies, and be grateful that at night, we may, thanks to Ian Fleming’s durable and infinitely renewable super spy, tuck in our children without undue fear.

Or so we like to think.

Onward.

Mark Rigney has published three stories in the Black Gate Online Fiction library: ”The Trade,” “The Find,” and “The Keystone.” Tangent called the tales “Reminiscent of the old sword & sorcery classics… once I started reading, I couldn’t stop. I highly recommend the complete trilogy.” In other work, Rigney is the author of ”The Skates,” and its haunted sequels, “Sleeping Bear” and Check-Out Time, forthcoming in 2014.

What I liked most about Skyfall (and I liked almost everything about Skyfall) is that it’s the first Bond movie I can remember that provided back story and context.

You know Bond fails in this movie? M dies thus the villian of the piece has his victory. Ken Hite and Robin Laws on their podcast go to town on the movie because it abandons what makes Bond a hero…

Great Line that should be read, re-read, and absorbed (the re-read again) by most of the ‘civilized’ world: “James Bond is the blunt tool by which civilized western society maintains its primacy, its safety, and its hegemony.”

Fun read Mark.

@Robert: Yes, Bond failed, but I’m not sure he abandoned what makes him a hero. It was perhaps the plot that forced his hand, but it was the progression of an iconic character seeking relevance, as Mark says “uncertain of his exact identity and purpose.” I think he did still pursue what makes him a hero, but due to his hesitation (brought on by many causes), he will bear the consequences, maybe deeper than ever. The truth will out in his next appearance.

Interesting post. I’ve never read Bond criticism that compares him to the mainstays of sword and sorcery and fantasy genres. That said,and despite my general agreement with your argument, I have two issues with the essay.

One) I would argue that Connery is still the best Bond with Craig a very close second.

Two) I’m not sure what the aim was with the whole ronin/ gunslinger section. Personally, I don’t think it quite works.

But again, over all, a very interesting essay with a lot of food for thought. Especially with your argument for why Bond remains relevant.

Brilliant! Yes.

I wish they had addressed the continuity, though. James Bond need not have been born Bond.

I refer you all to the James Bonding podcast on the Nerdist network – the hosts are ploughing through all the movies – enjoyable, funny and some interesting insights from their guests, particularly the contrasting female perspectives on Goldfinger and Casino Royale.

Odd that my SKYFALL piece wound up getting posted on, effectively, Christmas Eve. With the notable exception of Christmas Jones, I can’t say that I view James Bond as an especially seasonal offering.

Joe H. – Back story. Context. Hollywood always catches on to the good stuff eventually.

Robert – If the aim is protecting M, he does indeed fail. It’s not the first time: he failed to apprehend (or kill) Ernst Stavro Blofeld, not to mention SMERSH, at least once in the books, so this seems consistent to me. Also, I don’t mind a hero who fails on occasion. We could accuse Aragorn of much the same, or even Boromir. Elric’s story is almost nothing but failure. Obi Wan Kenobi comes out of retirement only to witness the destruction of Alderan (sp?). To me, SKYFALL ends on an uptick: Bond will take up M’s mantle and soldier on, this time with a new M (Ralph Fiennes) at the helm. The mission continues.

Jason – Glad you liked that line. Color me blushing.

Sftheory1 – The sword-swinging heroes and western gunslingers, etc., are all variations on the hero-archetype. I don’t want to play too many Joseph Campbell cards, but as a writer, I think a lot about protagonists. Their similarities. Their differences. Given the venue hosting this blog, it seemed impossible not to compare Bond to Elric, or even Judge Roy Bean. : )

MH Page – Bond need not have been born Bond? No, I suppose not. But I think you’re not referring specifically to the surname? Or are you? Either way, glad you liked the post.

Robert Round Two – I wonder if female film criticism is becoming somewhat kinder to Bond after (or because of) Skyfall. I wonder if BG regulars Violette, Sue, Claire, or Sarah will care to weigh in here?

Thank you all for reading!

On the other hand, I think there’s much Hollywood could learn from the Bond series — primarily the fact that Bond doesn’t _need_ an origin or backstory, at least not explicitly told. He’s a spy named Bond who goes up against villains; that’s all we really _need_ to know, and we know that going in.

I look forward to the day when superhero movies, especially for major, well-known characters, don’t feel the need to start over with the origin story every time they “reboot” the franchise.

[…] Skyfall: In Which a Pulp Hero Meets the 21st Century […]

[…] long ago, I wrote up an appreciation of Skyfall, the latest James Bond vehicle. Bond is most certainly a contemporary, if world-weary, hero. He […]

I believe that this was worst James Bond movie ever; discarding any vestiges of Fleming’s hero. Instead we get a mix of psychobabble and parts of movie plots from Batman to the Transporter.