World Building Historical Fiction using Military Thinking

If you read my blog, you’ll know I’m not a great fan of authorial self loathing and all that angst. However, when I got the gig to write Historical Adventure tie-ins for the Paradox War of the Roses game, I was a bit terrified. Rather than angsting over my ability to tell a story — I’d signed the contract so it was bit late for that! — I was overwhelmed by the task of using a real world historical setting.

Obviously, I was afraid of missing an obvious facet of Medieval life and then being pounced at by some of the hundreds of thousands of members of the Living History/Historical Reenactment/SCA/HEMA community.

However, the most pressing problem was; How was I to grok a historical setting well enough for it to become a my sandbox? I’d tackled this once before when writing a YA Dark Age yarn and found that a lot of the thinking had already been done for me by a group whose lives and, sometimes, homeland relied on untangling the world in order to make systematic sense of it: the Military…

Though not all the conflict is physical, an archetypal adventure story is not so different from a series of one or more combat missions. Simplifying greatly, military thinking makes sense of these on three levels:

- Strategic – The broad movement of armies in the pursuit of long term objectives driven by economics, diplomacy, and politics; “In order to secure our flanks, we shall make this country submit to us and do so by invading from the north and seizing its capital city.”

- Operational – Maneuvering towards objectives during the resulting campaigns and battles; “You will seize these bridges and hold them so that our tanks can use them.”

- Tactical – Achieving the objectives through fighting anything from a fullscale battle to a squad level action; “You guys set the mortar up over there and lay down smoke…”

This gives us three different ways of seeing anything in our story world.

Take the Mountains of Peril:

- Strategic – “The Mountains of Peril are dangerous and hard to cross but we need to get to the other side in order to surprise the enemy.”

- Operational – “This is the best route to use, try to avoid goblins.”

- Tactical – “Quick, into this cave and set up the flame caster!”

Each level reflects the implications of the one below it. Thus, at the strategic level, it’s enough to know that our protagonist should probably avoid the Mountains of Peril. We do not need to know about the goblins; these just provide colorful detail.

The implications for Fantasy world building are fairly obvious; don’t put in something at one level that will mess up the others.

Edgar Rice Burroughs famously gave his Martians “radium rifles” and then had to more or less pretend he had not. However, let’s use my “flame caster” as an example. If it changes the tactics when facing goblins, does that change the operational picture when we cross the Mountains of Peril? If so, then the Mountains of Peril now have a different strategic significance. Worse, this new weapon sounds pretty technical, perhaps it gives city states the edge over their feudal neighbors — now the whole strategic picture has changed including, ultimately, the structure of society and the economic system. That’s fine if that’s what the novel is about. Otherwise I just broke my world.

Thankfully, History is less fragile than Fantasy… as long as you do your research. We know that nothing lurking in the lower levels can break the upper levels unless it did, at which point we can see it at that level–the longbow or the pike formation being good examples.

Immediately — for me at least — the research becomes less intimidating since the three levels more or less correspond to stages of the writing work:

- Strategic — High concept, central myth, writing synopsis: I wanted my first War of the Roses book to be about a young gentleman trying to hang onto his land. This meant knowing about the political situation and its intersection with things like the legal system. I researched the various factions, “maintenance” and livery, the concept of “good lord”.

- Operational — Chapter outline: I needed to know about law and disorder in the shires, noble estates, rates of overland travel and accommodation, and the composition of retinues and noble households.

- Tactical — Scene outline. Actual text: Now I was into the nitty-gritty details. This meant combat of course, but also the context for combat, including interiors of inns and manor houses, which I needed anyway for the less violent interactions. It also entailed a detailed knowledge of courtesy — who is “sir” and who is “my lord” — and some sense of the costume.

This helps me focus on what I need to know, and ignore the tug of what I do not. For example, I didn’t read up on monasticism, towns, law courts, midwifery, or folk customs… this time.

M Harold Page (www.mharoldpage.com) is a Scottish-based writer and swordsman. His Paradox War of the Roses novels The Sword is Mightier and Blood in the Streets are both available on Amazon.

Great write-up. It’s so important to understand your story on all these different levels. Thanks, man.

Again a great article. Can I suggest that there is a ‘Theatre’ level in this?

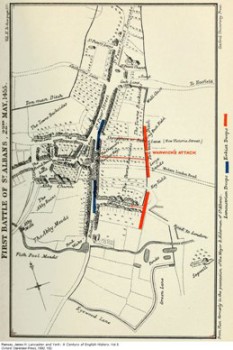

The landscape against which you set the book is another level to understand. You need to know where the Mountains of Peril are before getting into the strategic layer. For the War of the Roses you need to understand where in England you want to set your story and what the landscape brings. A solidly Lancastrian area in the southeast would be very different to a more split area in central England. This will trickle down into your strategic layer.

Yes, “Theatre” is a valid addition. However, I personally prefer just to roll that into Strategic because these layers map to authorial tasks.

This is a very helpful post. A work in progress I’ve shelved for years will eventually be easier to pick up for this approach. Thanks!

It’s one of those secrets hidden in plain sight, isn’t it? Glad this helps!

[…] World Building Historical Fiction using Military Thinking: Don’t fall down the rabbit hole of research or worldbuilding. Instead use a layered approach, focussing your world building as you descend from Strategic (villas exist and can be raided for supplies), through Operational (this villa sits on this ground amidst these fields), to Tactical (here is the ground plan of the villa and here are the people guarding it) level. […]