Ancient Worlds: Waking the Dead

As we approach Halloween, I’ll be taking a little detour (appropriate!) from our trip through the Odyssey to highlight some of the more horror-centered elements of ancient literature. First up? How about a raising of the dead to chase our trip to the Underworld last week?

Necromancy is a staple of the fantasy genre. It’s also one of the oldest standards out there. Long before Mary Shelley put a scientific spin on the practice, raising the dead was a popular way to impress people.

And terrify them.

And, given the methods involved, probably gross them out.

Why is necromancy so popular? Maybe it’s because something in us sees crossing that line between life and death as the ultimate power. Maybe it’s a kind of remnant of ancestor worship from an ancient past. Or maybe it’s because we all harbor the hope that once we shed the mortal coil, there will be answers.

(Although, as a magician friend of mine once said, “If your Uncle Jimmy was a dumbass when he was alive, why do you think he’ll be any smarter now that he’s dead?”)

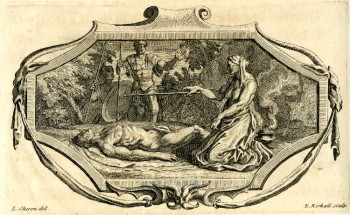

We see necromancy in the Bible, when King Saul consults the Witch of Endor. (image) We see it in Homer, when Odysseus goes to visit the deceased Tiresias. The geographer Strabo (trust me, geography books used to be a lot more interesting) talks about necromancy in the Persian Empire.

But my favorite ancient gravediggin’ witch has to be Erichtho. (Warning: I’m a bit biased, since I did my dissertation on the epic she’s featured in. I promise, I won’t make you read it.)

Lucan’s Pharsalia is an epic poem on the Roman Civil War. The big one. The one that made Caesar Caesar, the reason the Russians had Czars instead of Pompeys. If you haven’t heard of it, you’re in the vast majority, and all you really need to know for now is that if they made a movie, Tarantino would be your best bet.

About midway through the poem, Sextus Pompey goes off in search of a necromancer to find out how the next day’s big battle is going to turn out. (Answer: very badly.) He wanders the battlefield until he finds Erichtho, going up and down among the dead and gathering spare parts.

Erichtho is not just any witch. No, this is a bona fide Thessalian Witch. Lucan tells us that these witches can command the sun and moon, the tides, and the earth itself. They can kill a man with their spells, or bring him back to life. They possess all the secrets of magic, spells, and poisons,and even the gods are afraid of them.

This is no smouldering temptress, and Erichtho is about as far from Circe as you can get. Rather than living on a private island surrounded by pets, Erichtho haunts graveyards, and when Sextus finds her, she is literally hanging off a dead body by her teeth, gnawing pieces off.

…when the dead are coffined in stone, which drains off the internal moisture, absorbs the corruption of the marrow, and makes the corpse rigid, then the witch eagerly vents her rage on all the limbs, thrusting her fingers into the eyes, scooping out gleefully the stiffened eyeballs, and gnawing the yellow nails on the withered hand…

And because of course this is the woman you want to stop and ask for advice, he begs her to tell him the outcome of the following day. She agrees, grabs a nearby corpse, and proceeds to dredge the poor dead guy’s soul out of Hades and force it back into his mutilated corpse.

This process is fascinating. If you’re into that kind of thing. After putting together a truly disgusting potion and pouring it into the body, she calls on the gods of Hades to send the dead man’s spirit back. When that isn’t working fast enough, she begins to threaten them. She tells Hekate she’ll tell the other gods what she looks like without her makeup on. She threatens to open up Hades and drive out the Furies so that they are powerless. And most interesting of all, she threatens to tell everyone why exactly Persephone stays with Hades.

It’s all grotesque and oddly specific and, frankly, really weird.

Which is what it should be: if raising the dead were easy, everyone would do it. From an artistic perspective, this is Lucan showing off. He is, if not outright inventing, rapidly expanding the horror genre, and authors from Lovecraft to King are drinking from the same well. So if you liked Pet Semetary, Anita Blake, or the works of Garth Nix, you should lift a glass to poor, mostly-forgotten, Lucan and his compatriots in the Ancient World.

Elizabeth: Do you mind giving me another clue about your dissertation? I’m an old Lucan (and Erictho) fan, and I’d love to read it. But I’ve been googling for it without success.

The necromancy scene in book six is the apex of Lucan’s Lucanity, and sometimes when I’m reading him I want to shout, “STOP THE LUCANITY!” But the vivid and particular disgustingness of this scene is something I find myself drawn to reread again and again. Likewise the extispicy in book 1 and the snakes in book 9. The storm in book 4 and the scene with the Pythia in book 5 are weird worldmaking also.

I was reading Seneca’s OEDIPUS once and it occurred to me that these guys in the Silver Age really are writing horror fiction, or at least dark fantasy. I suppose if you lived in Rome under the later Julio-Claudians, that was a comfortable genre to write in…

Ahhhahahaha… “Stop the Lucanity…”

My diss was published under my married name, Elizabeth Brinnehl. If you promise not to hold it against me, I can send you a copy.

I tracked it down through UMI dissertations, and am getting a copy through my library. I’m looking forward to reading it. Which not something I can usually say about a dissertation.