Shock of the New: Thea von Harbou, Fritz Lang, and Metropolis

I’ve always had a fascination with Frtiz Lang’s Metropolis that I’ve never been able to explain. Obviously, it’s a visually powerful film and a tremendous influence on later films and later sf. But that imaginative magnificence seemed almost disconnected from the actual story of the movie. To a large extent, that’s because the Metropolis I knew for most of my life was a greatly-reduced version of Lang’s film. On its premiere in 1927, the movie was 4189 metres (13,823 feet) long, and ran 153 minutes; it was subsequently edited heavily, down to about 3100 to 3200 metres, without the input of husband-and-wife team of director Fritz Lang and scriptwriter Thea von Harbou. For decades, only short versions of Metropolis were believed to have survived, with major subplots and characters missing from the movie. A 2002 re-edit from rediscovered footage recreated something close to the original 1927 film and a 2010 version, based on a newly-recovered negative of the film, finally returned Metropolis to Lang and von Harbou’s original vision. Still, even seeing the whole thing, I have that sense of a kind of gap between the literal content of the film and what might be called its latent content — the mythic feel of the world it imagines.

I’ve always had a fascination with Frtiz Lang’s Metropolis that I’ve never been able to explain. Obviously, it’s a visually powerful film and a tremendous influence on later films and later sf. But that imaginative magnificence seemed almost disconnected from the actual story of the movie. To a large extent, that’s because the Metropolis I knew for most of my life was a greatly-reduced version of Lang’s film. On its premiere in 1927, the movie was 4189 metres (13,823 feet) long, and ran 153 minutes; it was subsequently edited heavily, down to about 3100 to 3200 metres, without the input of husband-and-wife team of director Fritz Lang and scriptwriter Thea von Harbou. For decades, only short versions of Metropolis were believed to have survived, with major subplots and characters missing from the movie. A 2002 re-edit from rediscovered footage recreated something close to the original 1927 film and a 2010 version, based on a newly-recovered negative of the film, finally returned Metropolis to Lang and von Harbou’s original vision. Still, even seeing the whole thing, I have that sense of a kind of gap between the literal content of the film and what might be called its latent content — the mythic feel of the world it imagines.

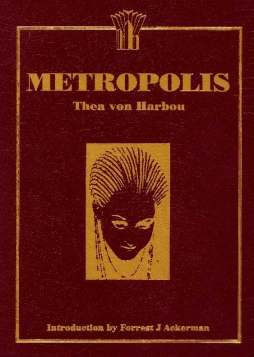

I didn’t entirely understand that gap until I read Thea von Harbou’s novel of the story. Published in 1925, the book clarifies a number of things: elements of the plot, the character motivation, and the symbolism. The use of the pentacle, the presence of a cathedral, the imagery of Babel and Apocalypse, the vision of Moloch superimposed over Metropolis’s machines, and especially the seemingly self-destructive urge of Joh Frederson, “the Master of Metropolis,” all become clearer. At the same time, I was conscious that I was reading the book with memory of the film always present. It seems to me that the two things, book and movie, work together to make a rich and full experience out of a distinctive fusing of science fiction and the gothic.

It has to be said that there’s been some difference of opinions about the book. Critic Holger Bachmann describes the novel as “a disparate, trivialized collection of motifs from various literary sources,” and refers to its “trivial romanticism.” John Clute, in the entry on von Harbou in the SF Encyclopedia, states that novel doesn’t have much of the film’s “symbolic force.” Personally, I tend to agree with Gary Westfahl, who stated that “von Harbou excelled in the one aspect of literary craftsmanship that critics tend to ignore because it is utterly beyond their ability to comprehend: the power of myth-making.” The sense of latent power I felt in the film of Metropolis has to do with its evocation of myth, both old and new, and I think that’s more clearly present in the book. It’s not a technical triumph like the film, but it’s not to be overlooked.

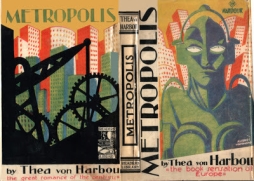

To explore that more, it’s worth first exploring the making of both film and novel, and the relationship of von Harbou and Lang (much of what follows, incidentally, comes from the book Fritz Lang’s Metropolis: Cinematic Visions of Technology and Fear, edited by Michael Minden and Bachmann). Lang wrote that the first idea for the film came to him in October, 1924, seeing New York City from the harbour as his ship came into port. But while it’s true that the movie does call to mind how dramatically automobiles and skyscrapers had reshaped the idea of the cityscape in less than a generation, one man has recalled reading an outline for Metropolis as early as April 1924, and von Harbou and Lang were reportedly at work on the script in June. At any rate, the novel came out in 1925, with a preface from von Harbou in which she said “I place this book in your hands, Fried.” Ufa, the production house behind the film, had a deal with a German magazine under which novelisations of movies in production were serialised in the magazine, with later installments illustrated by stills from the film shoot. Then the novel would be published as a standalone book just before the movie’s premiere. This was what happened with Metropolis.

To explore that more, it’s worth first exploring the making of both film and novel, and the relationship of von Harbou and Lang (much of what follows, incidentally, comes from the book Fritz Lang’s Metropolis: Cinematic Visions of Technology and Fear, edited by Michael Minden and Bachmann). Lang wrote that the first idea for the film came to him in October, 1924, seeing New York City from the harbour as his ship came into port. But while it’s true that the movie does call to mind how dramatically automobiles and skyscrapers had reshaped the idea of the cityscape in less than a generation, one man has recalled reading an outline for Metropolis as early as April 1924, and von Harbou and Lang were reportedly at work on the script in June. At any rate, the novel came out in 1925, with a preface from von Harbou in which she said “I place this book in your hands, Fried.” Ufa, the production house behind the film, had a deal with a German magazine under which novelisations of movies in production were serialised in the magazine, with later installments illustrated by stills from the film shoot. Then the novel would be published as a standalone book just before the movie’s premiere. This was what happened with Metropolis.

The novel seems to have been based on a relatively early draft of the script, which Lang and von Harbou reworked considerably. Lang started shooting in May of 1925; a determined perfectionist, he completed the film late in 1926, at a cost of 5.1 million reichsmarks — which, if my calculations are right, is the equivalent of over 250 million 2013 American dollars. The film premiered in January to mixed reviews, including a pan by H.G. Wells. Lang himself later expressed reservations about the movie, but that may be influenced by later events — both the development of his relationship with von Harbou, and the disquieting admiration the movie evoked in certain quarters.

The novel seems to have been based on a relatively early draft of the script, which Lang and von Harbou reworked considerably. Lang started shooting in May of 1925; a determined perfectionist, he completed the film late in 1926, at a cost of 5.1 million reichsmarks — which, if my calculations are right, is the equivalent of over 250 million 2013 American dollars. The film premiered in January to mixed reviews, including a pan by H.G. Wells. Lang himself later expressed reservations about the movie, but that may be influenced by later events — both the development of his relationship with von Harbou, and the disquieting admiration the movie evoked in certain quarters.

Lang and von Harbou divorced in 1933. With the rise of Nazism, Lang left Germany, but von Harbou stayed and continued to work under the Nazis. In fact prominent Nazis expressed admiration for Metropolis — by some accounts, it was Hitler’s favourite film. One postwar analysis of the movie suggests that it summed up the psychology of the Weimar era in a way that implicitly favoured the idea of a dictatorship. Personally, reading the book, I find few overtly Hitlerian aspects. There is some anti-Semitism, when a character is described having a greed that “appeared to hail from the Levant.” And there is certainly some racialist ideas; but I can’t say there’s anything that seems exceptional for a book written in the mid-20s. The setting of Metropolis is effectively a dictatorship, ruled by the hero’s father, but the politics and economy of the city are so stunted and underexplored it’s pointless to consider it as a realistic city: this is a dream-city, a myth of something that might be.

So what actually happens in the story? The main character is Freder, son of the master of Metropolis, Joh Fredersen. Freder’s interrupted in his leisure with the other sons of the upper class by a woman named Maria, who leads a group of children from the workers’ area of the city into the upper-class district: “Look, these are your brothers!” she says, first to the poor children and then to the rich youths. She and the children leave, and Freder sets out to learn about her and about the lives of the workers: he exchanges identities with one of the workers, and attends a secret meeting Maria leads in the workers’ underground home. Meanwhile, Joh Fredersen had plans of his own. He’s despatched his agent Slim to follow his son, while Joh himself visits his old friend and rival Rotwang, a scientist who has been working on a project to create artificial life. Years before, Joh stole away Rotwang’s true love, Hel, who died giving birth to Freder; now Rotwang’s almost perfected a robot with a female shape. Joh directs him to give the robot the form of Maria, so that it can lead the workers astray. Rotwang does; Freder walks in on the false Maria plotting with Joh; the false Maria leads the workers to destroy the machines that run Metropolis, and thereby almost brings about the death of the workers’ children. In a final confrontation the false Maria’s destroyed, while Freder saves the true Maria from Rotwang.

So what actually happens in the story? The main character is Freder, son of the master of Metropolis, Joh Fredersen. Freder’s interrupted in his leisure with the other sons of the upper class by a woman named Maria, who leads a group of children from the workers’ area of the city into the upper-class district: “Look, these are your brothers!” she says, first to the poor children and then to the rich youths. She and the children leave, and Freder sets out to learn about her and about the lives of the workers: he exchanges identities with one of the workers, and attends a secret meeting Maria leads in the workers’ underground home. Meanwhile, Joh Fredersen had plans of his own. He’s despatched his agent Slim to follow his son, while Joh himself visits his old friend and rival Rotwang, a scientist who has been working on a project to create artificial life. Years before, Joh stole away Rotwang’s true love, Hel, who died giving birth to Freder; now Rotwang’s almost perfected a robot with a female shape. Joh directs him to give the robot the form of Maria, so that it can lead the workers astray. Rotwang does; Freder walks in on the false Maria plotting with Joh; the false Maria leads the workers to destroy the machines that run Metropolis, and thereby almost brings about the death of the workers’ children. In a final confrontation the false Maria’s destroyed, while Freder saves the true Maria from Rotwang.

There’s more to it, though, and much of that is what has always fascinated me about the story. Rotwang’s home dates back to before the creation of the modern Metropolis; it was the home of an occult magician, and is decorated with the Seal of Solomon — the pentacle. There is a gothic cathedral in the heart of the modern city, and in the book there’s a sect of “Gothics,” religious fanatics who make trouble for Joh Fredersen. The false Maria is explicitly compared to the Whore of Babylon in the Book of Revelations. Metropolis itself is Babylon, with the Tower of Babel at the heart of the city. Among all the super-science, then, there is a core of religious symbolism, made manifest in the characters: Joh as the father Jehovah, Freder as the redeeming Christ, Maria as Magdalene and Virgin. Rotwang, scientist and wizard, as the devil: no coincidence he and the Christ-figure Freder have their final confrontation on top of the highest church in the land. Lang himself observed this about the movie:

Mrs. von Harbou and I put in the script of Metropolis a battle between modern science and occultism, the science of the medieval ages. The magician was the evil behind all the things that happened: in one scene all the bridges were falling down, there were flames, and out of a Gothic church came all these ghosts and ghouls and beasties. I said “No, I cannot do this.” Today I would do it, but in those days I didn’t have the courage.

The magical aspects of the story are stronger in the novel, and more clearly explained. The mythic symbolism is more consistent. Early in the film, Freder has a vision of the machines that run the city as the maw of Moloch; that reference is much clearer in the book. Here’s a quote, as Freder describes what he saw among the machines:

I only know what I saw — and that it was dreadful to look upon … I went through the machine-rooms — they were like temples. All the great gods were living in white temples. I saw Baal and Moloch, Huitzilopochtli and Durgha; some frightfully companionable, some terribly solitary. I saw Juggernaut’s divine car and the Towers of Silence, Mahomet’s curved sword, and the crosses of Golgotha. And all machines, machines, machines, which, confined to their pedestals, like deities to their temple thrones, from the resting places which bore them, lived their god-like lives: Eyeless but seeing all, earless but hearing all, without speech, yet, in themselves, a proclaiming mouth — not man, not woman, and yet engendering, receptive, and productive — lifeless, yet shaking the air of their temples with the never-expiring breath of their vitality. And, near the god-machines, the slaves of the god-machines: the men who were as though crushed between companionability and machine solitude. They have no loads to carry: the machine carries the loads. They have not to lift and push: the machine lifts and pushes. They have nothing else to do but eternally one and the same thing, each in this place, each at his machine. Divided into periods of brief seconds, always the same clutch at the same second, at the same second. They have eyes, but they are blind but for one thing, the scale of the manometer. They have ears, but they are deaf but for one thing, the hiss of their machine. They watch and watch, having no thought but for one thing: should their watchfulness waver, then the machine awakens from its feigned sleep and begins to race, racing itself to pieces. And the machine, having neither head nor brain, with the tension of its watchfulness, sucks and sucks out the brain from the paralysed skull of its watchman, and does not stay, and sucks, and does not stay until a being is hanging to the sucked-out skull, no longer a man and yet not a machine, pumped dry, hollowed out, used up. And the machine which has sucked out and gulped down the spinal marrow and brain of the man and has wiped out the hollows in his skull with the soft, long tongue of its soft, long hissing, the machine gleams in its silver-velvet radiance, anointed with oil, beautiful, infallible — Baal and Moloch, Huitzilopochtli and Durgha. And you, father, you press your fingers upon the little blue metal plate near your right hand, and your great glorious, dreadful city of Metropolis roars out, proclaiming that she is hungry for fresh human marrow and human brain and then the living food rolls on, like a stream, into the machine-rooms, which are like temples, and that, just used, is thrown up …

It’s prolix, but its identification of the machines with temples and gods is resonant. Not only is the idea powerful, uniting the vision of the future with the myths of the past, but it’s a recurring idea in the text — something I feel is more consistent in the novel, as well as broader, drawing from more mythologies.

In terms of the writing, the breathless tone is kept up throughout the book. Personally, I find it’s overwrought but not uninteresting; the relentless passion contrasts with the mechanised image of the future. That said, this is not the finest of prose. Even with all allowances made for infelicities in translation (I read, and quote here from, an uncredited 1927 translation published by the Readers Library and republished in 1975), it’s unsubtle and inelegent. I will say that some of the repetition is probably a deliberate device: von Harbou repeats verbal tags in a kind of cod-Homeric fashion, which at its best hits the effect of a kind of prose leitmotif.

In terms of the writing, the breathless tone is kept up throughout the book. Personally, I find it’s overwrought but not uninteresting; the relentless passion contrasts with the mechanised image of the future. That said, this is not the finest of prose. Even with all allowances made for infelicities in translation (I read, and quote here from, an uncredited 1927 translation published by the Readers Library and republished in 1975), it’s unsubtle and inelegent. I will say that some of the repetition is probably a deliberate device: von Harbou repeats verbal tags in a kind of cod-Homeric fashion, which at its best hits the effect of a kind of prose leitmotif.

Still, granted that von Harbou doesn’t have the technical gift in her medium that Lang has in his, the latent power of the story seems clearer in prose. You can see more clearly the contrast of past and present, of magic and technology, of gods and gadgetry. Oddly, it’s also I think less resonant — Lang’s visual sense is a crucial part of what makes Metropolis great. There’s a sense in which the story lives, at least for me, because I have the imagery of the film already present in my memory, and so can reassemble it in the slightly different form that the novel suggests.

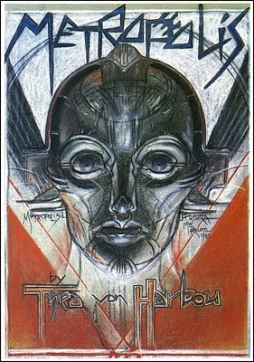

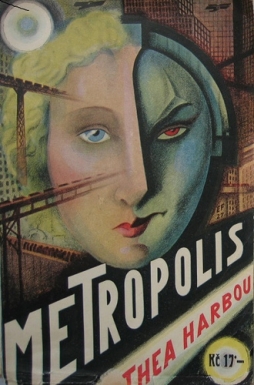

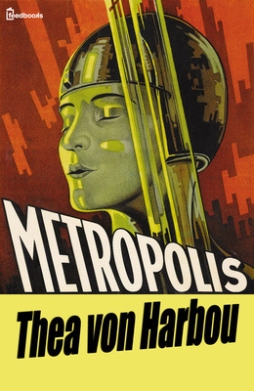

There is, incidentally, one significant image changed considerably from book to film. The conception of the female robot (called “Machina” and “Parody” in the novel) is very different from the movie, with von Harbou imagining a creature with “a body as though made of crystal, through which the bones shone silver.” Lang’s gynoid is something quite other, perhaps a concession to the limitations of special effects of the time. It’s perhaps appropriate that the most famous image of the film is a purely filmic creation, a strictly visual myth.

If I seem to be speaking here an awful lot about myth and dream, there’s a good reason for it. As a literal projection of the future, the story doesn’t make much sense. H.G. Wells noticed as much; he wondered what the workers were actually making at their hellish jobs, and what sort of economy sustained the city. The book suggests an extensive rural hinterland supplies food to the city, but says nothing about how the distribution of goods is actually done. There’s a kind of opium den called Yoshiwara, but how Yoshiwara fits into the overall context of the city is unclear. Above all, the story’s moral is almost incoherent: “The mediator between head and hands must be the heart,” says the novel and the film, but in the context of a whole society that simply doesn’t make sense. Who appoints some people as Head and others as Hands? How does one move from one position to another? The vision of unrelieved soul-deadening labour Freder describes isn’t ultimately abolished or overthrown: work goes on, somehow made easier by the existence of a “mediator.”

If I seem to be speaking here an awful lot about myth and dream, there’s a good reason for it. As a literal projection of the future, the story doesn’t make much sense. H.G. Wells noticed as much; he wondered what the workers were actually making at their hellish jobs, and what sort of economy sustained the city. The book suggests an extensive rural hinterland supplies food to the city, but says nothing about how the distribution of goods is actually done. There’s a kind of opium den called Yoshiwara, but how Yoshiwara fits into the overall context of the city is unclear. Above all, the story’s moral is almost incoherent: “The mediator between head and hands must be the heart,” says the novel and the film, but in the context of a whole society that simply doesn’t make sense. Who appoints some people as Head and others as Hands? How does one move from one position to another? The vision of unrelieved soul-deadening labour Freder describes isn’t ultimately abolished or overthrown: work goes on, somehow made easier by the existence of a “mediator.”

In fact, though, the “Head and Hands” statement makes perfect sense if applied to the individual psyche. In that sense, Metropolis is a representation of a single soul: the veneer of modern rationalism above atavistic unconscious fears and beliefs. The body toiling in the service of a divided consciousness. Joh Fredersen’s willingness to risk destruction for the city just so that (as the book tells us) his son may have something to redeem becomes an image of self-destruction. Symbolically, Freder overthrowing Rotwang and stepping forward to “mediate” is a healing of the soul, a setting-in-order of the person as a whole. I note that neither book nor film describe the city as hosting people of different cultures, only of different classes. The novel has one figure, the man called September who runs Yoshiwara, that seems to represent some kind of multicultural identity; but there’s a non-specificity about him that instead resonates with the syncretic imagery of the various gods of Freder’s vision. So there are classes in Metropolis, but not cultures; the city’s a monolith, most unlike a large city of the modern world, and so seems even more the image of a single mind.

(As an aside, and a contrast, I note that the Brazilian metal band Sepultura have named their upcoming album The Mediator Between the Head and Hands Must Be the Heart. Says the guitarist, Andreas Kisser: “I live in São Paulo, Brasil, one of the big[gest] metropolis in the world with more than 20,000,000 people living and working in it. I know how it is to live in daily chaos, our music reflects a lot of that feeling.” But then, one of the hallmarks of myth is the way it’s interpreted differently by different people.)

(As an aside, and a contrast, I note that the Brazilian metal band Sepultura have named their upcoming album The Mediator Between the Head and Hands Must Be the Heart. Says the guitarist, Andreas Kisser: “I live in São Paulo, Brasil, one of the big[gest] metropolis in the world with more than 20,000,000 people living and working in it. I know how it is to live in daily chaos, our music reflects a lot of that feeling.” But then, one of the hallmarks of myth is the way it’s interpreted differently by different people.)

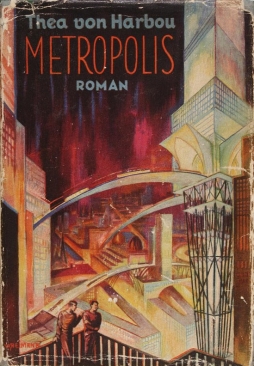

So the metaphor seems to overwhelm the literal: that is, the metaphor of the city works as a potent symbol, but the description of the city doesn’t depict a convincing city as such. Still, there’s something to the way Metropolis imagines its Metropolis. The city isn’t a literal city, but it is an archetypal city. Yet it’s no traditional archetype, neither Babylon (despite its claims) nor the New Jerusalem. It’s a myth of a different kind. A myth for the future. A mythic idea, a reimagining of the city, a vision of what the city will be. Here is the future, only a couple pages after Freder’s neurotic vision of the old gods haunting the machines enslaving the working class:

Joh Fredersen’s eyes wandered over Metropolis, a restless roaring sea with a surf of light. In the flashes and waves, the Niagara falls of light, in the colour-play of revolving towers of light and brilliance, Metropolis seemed to have become transparent. The houses, dissected into cones and cubes by the moving scythes of the search-lights gleamed, towering up, hoveringly, light flowing down their flanks like rain. The streets licked up the shining radiance, themselves shining, and the things gliding upon them, an incessant stream, threw cones of light before them. Only the cathedral, with the star-crowned Virgin on the top of its tower, lay stretched out, massively, down in the city, like a black giant lying in an enchanted sleep.

The image of Niagara Falls seems particularly appropriate here: there’s something of the New World about Metropolis, something recalling Lang’s vision of New York, even if it’s implied that it’s actually physically located somewhere in Europe, with an ancient cathedral at its core. The old church like a fairy-tale giant remains, but the rest of the city is a contrast, a vision of the world to come. Perhaps even a new kind of vision, lit by a new kind of light. To me, there’s nothing of the steampunk in Metropolis, giant machines notwithstanding. It’s a point where the Victorian dreams of the future are set aside, to be replaced with something more, something that still retains a startling sense of potency. In this context the mention of Yoshiwara has an almost cyberpunk feel to it, an urbanely international echo; in fact, it is literally a reference to a district of Edo where prostitution was allowed (until 1958), and in the story is a venue for the consumption of a futuristic drug. Ruled by a man with a handle (‘September’) instead of a name, promoting itself with guerrilla marketing, it strongly calls to mind the quasi-legal demimonde of the cyberpunk.

The image of Niagara Falls seems particularly appropriate here: there’s something of the New World about Metropolis, something recalling Lang’s vision of New York, even if it’s implied that it’s actually physically located somewhere in Europe, with an ancient cathedral at its core. The old church like a fairy-tale giant remains, but the rest of the city is a contrast, a vision of the world to come. Perhaps even a new kind of vision, lit by a new kind of light. To me, there’s nothing of the steampunk in Metropolis, giant machines notwithstanding. It’s a point where the Victorian dreams of the future are set aside, to be replaced with something more, something that still retains a startling sense of potency. In this context the mention of Yoshiwara has an almost cyberpunk feel to it, an urbanely international echo; in fact, it is literally a reference to a district of Edo where prostitution was allowed (until 1958), and in the story is a venue for the consumption of a futuristic drug. Ruled by a man with a handle (‘September’) instead of a name, promoting itself with guerrilla marketing, it strongly calls to mind the quasi-legal demimonde of the cyberpunk.

Against this new conception, the revolt of the workers is more than a Luddite uprising, though there’s some of that in there (complete with the class issues that inspired the original Luddites). Their destruction of the machines that enslave them and yet keep their homes safe from the deluge is a kind of revel, led by the demonic machine-Maria. It’s an uprising of the unconscious, if you like, of atavistic primitive forces that threaten to undermine everything that reason has built.

It’d be a mistake to make this symbolism too programmatic, though. To me the overall pattern seems to make sense in broad strokes. But any successful symbol operates on more than one level, and can never be entirely ‘explained.’ Metropolis has something to say about gender and sexuality (given that the main characters are all male except Maria, the sense of her as an anima-figure is strong; Freder finding the machine-Maria with his father is a primal Oedipal image), about religion, about psychology, about magic and science. What I think is so fascinating is that it says all this through a vocabulary that has rarely been used in quite the same way. At almost exactly the same time Lang was shooting Metropolis Hugo Gernsback was first identifying science fiction as a separate kind of story, and constructing a tradition of scientific romances to define the genre. Before long there came to be an insistence within science fiction on the importance of science to the fiction. Metropolis, both novel and film, is very different.

It’d be a mistake to make this symbolism too programmatic, though. To me the overall pattern seems to make sense in broad strokes. But any successful symbol operates on more than one level, and can never be entirely ‘explained.’ Metropolis has something to say about gender and sexuality (given that the main characters are all male except Maria, the sense of her as an anima-figure is strong; Freder finding the machine-Maria with his father is a primal Oedipal image), about religion, about psychology, about magic and science. What I think is so fascinating is that it says all this through a vocabulary that has rarely been used in quite the same way. At almost exactly the same time Lang was shooting Metropolis Hugo Gernsback was first identifying science fiction as a separate kind of story, and constructing a tradition of scientific romances to define the genre. Before long there came to be an insistence within science fiction on the importance of science to the fiction. Metropolis, both novel and film, is very different.

At every turn it seems that the story’s flavoured by myth; is in fact shaped by myth. The practical science, the literal speculation, is less important than the imagery. It’s as much fantasy as science fiction. It’s quite accurate to say that the roots of Star Wars are to be found here. The fictional Metropolis becomes the ancestor, by way of Trantor and Apokolips, of Coruscant. Rotwang, as many have observed, is the scientist as magus, working wonders in his crazy cursed house (which is clearly larger on the inside than it is on the outside) with his Seal of Solomon.

There’s a point in the book where Freder, recovering after the psychic shock of seeing his father with the machine-Maria, looks out the window of his room and sees “Around the ridge of the roof of the house right opposite him there ran, in a shining border, a shining word, running in an everlasting circuit around, behind itself.” The word is “Phantasus.” Phantasus was literally a Greek god, son of Hypnos, the bringer of dreams of inanimate things (so presumably of cities). It’s also the name of a poetry collection by Arno Holz and, what I think is more important, an anthology of literary fairy tales written by Ludwig Tieck. I think that’s important because I think Metropolis, in either version but especially in its novel form, harks back to Tieck’s old traditions of Märchen and of the German Gothic story, as much as it also looks forward to the science fiction story as we know it now. The attractive woman who is actually an automaton — that’s a motif right out of E.T.A. Hoffmann. As much as Metropolis has a veneer of the future, it’s also in deep dialogue with the past. It’s updating the images of old tales for a new time.

There’s a point in the book where Freder, recovering after the psychic shock of seeing his father with the machine-Maria, looks out the window of his room and sees “Around the ridge of the roof of the house right opposite him there ran, in a shining border, a shining word, running in an everlasting circuit around, behind itself.” The word is “Phantasus.” Phantasus was literally a Greek god, son of Hypnos, the bringer of dreams of inanimate things (so presumably of cities). It’s also the name of a poetry collection by Arno Holz and, what I think is more important, an anthology of literary fairy tales written by Ludwig Tieck. I think that’s important because I think Metropolis, in either version but especially in its novel form, harks back to Tieck’s old traditions of Märchen and of the German Gothic story, as much as it also looks forward to the science fiction story as we know it now. The attractive woman who is actually an automaton — that’s a motif right out of E.T.A. Hoffmann. As much as Metropolis has a veneer of the future, it’s also in deep dialogue with the past. It’s updating the images of old tales for a new time.

In some ways I think that’s clearer in the book than the film. But in either iteration I think it makes for a fascinating, uneasy tension; a pull between myth and science, resolved only partially by the attempt to use science to create a new myth. It is a strange and evocative attempt, in any form, and it is no wonder to me now that images from that story have haunted me. The film’s a greater work than the novel, no doubt, but both are valuable; like any myth, the tale grows the more it is retold. And, like any myth, the tale is greater than any one telling. Metropolis cannot, perhaps, ever be understood. Only experienced.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Ah, Metropolis — the original source for every city in every SF book and movie.

Lots of interesting insights here — I read the book (the Wildside reissue) a while back, but obviously wasn’t reading it this closely …

Thanks, Joe! Glad you enjoyed the piece!