More Than Whodunit: the Science Fiction Mystery

There’s a reason that crime or mystery is the genre most often mixed in with others. When you’re writing novel or short story, you generally go about it by finding a character and asking yourself what kind of problems a person like that would face. Then, of course, you give that person those problems; it’s the solving of the problems that forms the narrative of the story. Involving your character in a crime certainly makes for a nice problem, and of the crime problems available, murder is the one readers find most interesting – at least for novel-length narratives.

There’s a reason that crime or mystery is the genre most often mixed in with others. When you’re writing novel or short story, you generally go about it by finding a character and asking yourself what kind of problems a person like that would face. Then, of course, you give that person those problems; it’s the solving of the problems that forms the narrative of the story. Involving your character in a crime certainly makes for a nice problem, and of the crime problems available, murder is the one readers find most interesting – at least for novel-length narratives.

But mixing crime into your SF does present its own peculiar difficulties. As John W. Campbell suggested, it would be too easy for the writer to suddenly come up with a gadget or whizmo that would solve the crime. And Campbell was right to worry that writers might take that easy way out. Just as in fantasy mysteries, however, all you have to do to create great SF mysteries is respect the conventions of both genres.

Well, in a world where anything about writing can be summed up in the phrase “all you have to do is.”

Not all mysteries are of the classic “puzzle” type, the whodunit usually associated with Agatha Christie, but most do follow a few basic conventions. The criminal is revealed (at least to the reader); the solution makes reasonable sense within the parameters of the story (no deus ex machina); the readers had a reasonable chance of solving the problem for themselves (no withholding evidence). SF is the genre of change, exploring the impact of (usually) technological innovations or changes on humans and human society. So in the same way that fantasy mysteries have to take into account the supernatural elements of their imagined worlds, SF mysteries have to work with whatever technological changes make the world of the story different from ours. It’s how these changes lead to crimes, or help to solve them, that makes an SF mystery.

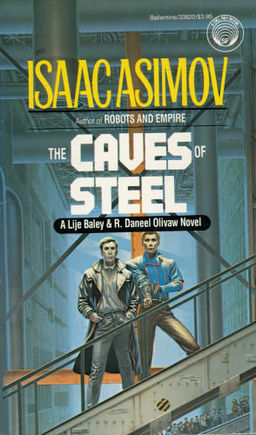

Like many SF and Fantasy writers, Isaac Asimov wrote straight mysteries as well, like Murder at the ABA, (in which he appears as himself in a minor role) and in his short stories about the Trap Door Spiders. He also wrote mystery SF short stories, like those featuring Dr. Wendell Urth, and there are a few of his early robot stories that could be considered crime stories. However, it’s the Robot Novels, featuring the crime-fighting duo Police Detective Elijah Bailey and his robot partner R. Daneel Olivaw, that are Asimov’s real contribution to SF mysteries.

It’s typical of Asimov, by the way, that he makes the technological change both the cause of the problem and the fix. It’s because robots have been taking over human jobs that the victim gets murdered; Elijah may lose his own job if Daneel solves the crime without him. How does the crime get solved? I leave you to learn that yourself.

It’s typical of Asimov, by the way, that he makes the technological change both the cause of the problem and the fix. It’s because robots have been taking over human jobs that the victim gets murdered; Elijah may lose his own job if Daneel solves the crime without him. How does the crime get solved? I leave you to learn that yourself.

Fond as I am of Asimov’s work, I have to say that my favourite SF mysteries come from Larry Niven. He’s not known primarily for his contributions to the SF crime subgenre, however he is known for playing “what if” with new and invented technologies, and a couple of these scientific changes led to two series of crime stories.

“The Alibi Machine” posits a tech breakthrough most of us would love to see: instantaneous matter transport in the form of jump booths, from individual person-sized versions, up to big freight-carriers. In various stories using this premise, Niven explores what that would mean to the travel, freight, and entertainment industries; but for me, it’s how the booth affects crime, and therefore the crime story, that’s most interesting. For one thing, jump booths do away completely with the concept of alibis. If you can be anywhere in the world within minutes, no one has an alibi for any crime. This would affect not only how police approached their investigations; but even how criminals – especially murderers, would plan their cover stories.

Niven suggests that jump booths could easily result in “flash crowds,” hundreds or even thousands of people jumping to a particular event or area at the same time. Impact on crime? Why, new opportunities for pick-pockets and looting, to say nothing of heists performed under the cover of a flash crowd. New opportunities for criminals always results in new solutions on the part of the police. . . or is that the other way around?

Where “the Alibi Machine” led to new criminal methods and methodology, the deceptively simple premise behind the “The Jig-Saw Man” introduced a new crime. There has been a medical breakthrough that completely does away with transplant rejection. Think about it: no more worries about blood type and no one dying from organ failure before a close enough match can be found. Anyone can donate an organ to anyone. Anyone at all. Even say, criminals on death row. I mean, they’re going to die anyway, aren’t they? Why waste all that blood, skin, tissue, and organs?

Say there’s a shortage of good organs – and there almost always is – wouldn’t people start supporting the death penalty? And wouldn’t they start voting for more and more crimes to be punishable by death? Sure they would, says Niven. The crime of the eponymous Jig-Saw Man? Jay walking.

But what’s the new crime, you ask? Organlegging. And what a winner from the story-telling point of view: kidnapping AND murder. And what’s the sentence for a convicted organlegger? I’m sure you can guess.

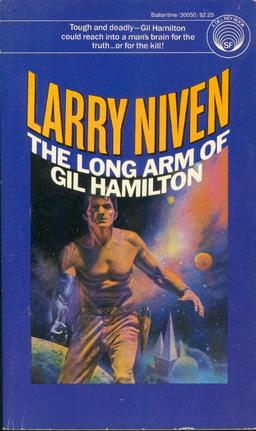

The stories associated with Niven’s story “The Jig-Saw Man” eventually became part of the Tales of Known Space, but before the continuum got quite that far, we have some of my favourite of Niven’s work, the Gil Hamilton stories. Gil is an ARM, an operative in the Amalgamation of Regional Militia, the United Nations Police. Their primary work is tracking down organleggers, which ultimately involves them with most homicides.

The stories associated with Niven’s story “The Jig-Saw Man” eventually became part of the Tales of Known Space, but before the continuum got quite that far, we have some of my favourite of Niven’s work, the Gil Hamilton stories. Gil is an ARM, an operative in the Amalgamation of Regional Militia, the United Nations Police. Their primary work is tracking down organleggers, which ultimately involves them with most homicides.

But Gil’s known as “the Arm” for more than where he works. Gil once lost his right arm asteroid mining, and he had it replaced by . . . but why don’t you find out for yourselves? You won’t regret it.

Violette Malan is the author of the Dhulyn and Parno series of sword and sorcery adventures, as well as the Mirror Lands series of primary world fantasies. As VM Escalada, she writes the soon-to-be released Halls of Law series. Visit her website www.violettemalan.com

Not to mention the short story ‘What Good is Glass Dagger?’ – one of Niven’s rare forays into fantasy. Sure the visuals could have done with a bit of work, but the plot (and the twist) were both pretty good.

Aonghus, one of my favourites of his work. I can’t believe I didn’t mention it in my last post, where I was talking about Fantasy mysteries. I’m collecting a list of other examples I’ve overlooked for a possible follow-up post.

[…] which I’ve lusted after ever since Violette Malan teased me with the cover in her article on science fiction mysteries last […]