Weird of Oz Dissects a Zombie!

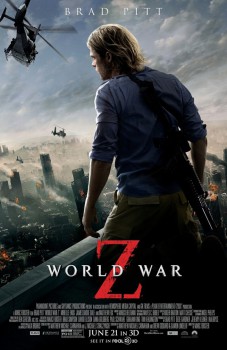

Now that zombie apocalypse has gotten its most mainstream imprimatur with a big-budget summer blockbuster starring Brad Pitt, I thought I’d take a break from my reading of Arak comic books this week to chime in on the trend. I’ll also revisit and share my original review of the book on which Pitt’s new star vehicle is “based” (and, for those of you who have read World War Z, you’ll know why I put that word in quotes).

Now that zombie apocalypse has gotten its most mainstream imprimatur with a big-budget summer blockbuster starring Brad Pitt, I thought I’d take a break from my reading of Arak comic books this week to chime in on the trend. I’ll also revisit and share my original review of the book on which Pitt’s new star vehicle is “based” (and, for those of you who have read World War Z, you’ll know why I put that word in quotes).

I’ve been a fan of zombie films since I was a teen (back in the ‘80s, Barbara Mandrell sang, “I was country when country wasn’t cool”; I guess I could say much the same thing about zombies), ushered into the land of the undead by late-night viewings of Night of the Living Dead (1968) and White Zombie (1932, starring Bela Lugosi, and that’s way old-school).

Zombies are big business these days, the virus finding new vectors to infect untapped audiences and turn them into fans. This unprecedented outbreak began in the early years of the new century with some very well-done and popular films including 28 Days Later (2002), Dawn of the Dead (2004 remake) and Shaun of the Dead (2004). Romero himself, the granddaddy of the whole genre, returned with Land of the Dead (2005) and a couple of subsequent installments in his ever-expanding zombie mythos.

More recently, the comic-book series The Walking Dead became a big hit among readers, then went on to be adapted into the AMC series that is currently one of the most popular shows on cable television. Zombie novels have become so ubiquitous, they now constitute their own sub-genre, like vampire or werewolf novels. You might also say zombies have now “jumped the shark,” following the lead of Twilight into teen romance territory (Warm Bodies by Isaac Marion, as well as, apparently, a slew of others in this latest fad. I haven’t read any of these, but I can only imagine: “Is that part of your lower intestine leaking from your abdomen, or are you just happy to see me?”).

More recently, the comic-book series The Walking Dead became a big hit among readers, then went on to be adapted into the AMC series that is currently one of the most popular shows on cable television. Zombie novels have become so ubiquitous, they now constitute their own sub-genre, like vampire or werewolf novels. You might also say zombies have now “jumped the shark,” following the lead of Twilight into teen romance territory (Warm Bodies by Isaac Marion, as well as, apparently, a slew of others in this latest fad. I haven’t read any of these, but I can only imagine: “Is that part of your lower intestine leaking from your abdomen, or are you just happy to see me?”).

Others have written interesting pieces on why zombies have become so popular (including Lev Grossman for no less than Time Magazine, with his 2009 article “Zombies Are the New Vampires”). I have myself weighed in elsewhere on psychological reasons why zombies are the premiere bogeyman of our day; when I taught a college course on the horror genre in film and literature a few years back, this was a topic of discussion. I won’t get into all that here, although it is fun to speculate on how a given generation’s most frightening monsters often sublimate or stand in for that generation’s most potent real horrors. I’ll just note that zombies have always been a perfect embodiment of at least three distinct horrors: 1) they can represent the mob mentality, being turned into one of the mindless masses, an un-individualized piece of the horde; 2) they are an excellent stand-in for the fear of contagion, a horrific substitute for AIDS and SARS and H1N1 and avian flu and Ebola and [fill in the blank with your own favorite pandemic]; 3) the very spectacle of a rotting corpse viscerally confronts us with the reality of our own mortality, namely, one day our bodies will rot away and all these pieces we are quite attached to will fall off, and the worms will quite enjoy them, yum yum (“The worms crawl in, the worms crawl out / The worms play pinochle on your snout”).

But, can I linger on this point just a moment more before we leave this particular dead horse behind, dear reader? I think there is one more fear to mention with regard to zombies; it’s one that doesn’t get much play in the literature I’ve read, and is only intermittently achieved by the writers and directors and actors and special-effects artists who work so damned hard to bring the undead to life. And that is the effect of the Unnatural. The Thing That Should Not Be!, as H.P. Lovecraft or, later, Stan Lee, might have declared like carnival barkers trying to lure us into the tent of freaks. With a corpse that is suddenly twitching, lurching upright, dragging itself toward you — while you know that it is still dead — you have something that you know cannot be and should not be. A corpse, in nature, has made the transition into that new state of being where it no longer moves; the spirit has fled, the soul or electrical impulses (or whatever you believe life energy to be) no longer animates this matter. If it does move, that means either A) a reflex twitch as some gas is expelled or the muscles settle in to the business of decomposing or B) this corpse is not a corpse after all! Death has been misdiagnosed; the patient is still alive. But if the patient gets up from the table and we know neither A nor B to be true, there is no option C. We then have the unnaturalness of the undead.

But, can I linger on this point just a moment more before we leave this particular dead horse behind, dear reader? I think there is one more fear to mention with regard to zombies; it’s one that doesn’t get much play in the literature I’ve read, and is only intermittently achieved by the writers and directors and actors and special-effects artists who work so damned hard to bring the undead to life. And that is the effect of the Unnatural. The Thing That Should Not Be!, as H.P. Lovecraft or, later, Stan Lee, might have declared like carnival barkers trying to lure us into the tent of freaks. With a corpse that is suddenly twitching, lurching upright, dragging itself toward you — while you know that it is still dead — you have something that you know cannot be and should not be. A corpse, in nature, has made the transition into that new state of being where it no longer moves; the spirit has fled, the soul or electrical impulses (or whatever you believe life energy to be) no longer animates this matter. If it does move, that means either A) a reflex twitch as some gas is expelled or the muscles settle in to the business of decomposing or B) this corpse is not a corpse after all! Death has been misdiagnosed; the patient is still alive. But if the patient gets up from the table and we know neither A nor B to be true, there is no option C. We then have the unnaturalness of the undead.

Incidentally, vampires, too, should elicit this unnatural horror of the undead, but they never do anymore. The way vampires are most often portrayed in works of popular culture these days is not that they are no longer living, but that they have somehow evolved into a new state of being, a different form of life. In this sense, they have not progressed downward toward corpse but upward toward an angelic state.

Zombies still have the power to convey this unnaturalness-of-the-undead thing, because, hey, there’s no concealing those milky eyes and that pallid skin and that leaking viscera. Ironically, this particular effect has been somewhat undermined with the past decade’s trend to make zombies more practically threatening. I’m talking, of course, about the trend of fast zombies, of zombies sprinting and somersaulting around like they could compete in Olympic-level gymnastics events — if the medals awaiting them at the end were made of brains. Yes, practically speaking, now the characters are more imperiled because it is not so easy to run from them or take your time to draw a bead for a good head shot. But the slow, lurching, lumbering zombie dance of yore more effectively conveyed that this thing is dead, that it shouldn’t be moving at all. Okay, ‘nuff said on that.

Last week I managed to sneak out and catch World War Z in the theaters. Then I came home and read several reviews, and I agree with the general consensus. It is very effective, overall, taking the zombie apocalypse to a world-wide scale. The outbreaks in previous movies — all the way back to Romero’s original — were usually worldwide, but you only got the sense of that from radio broadcasts or snippets of TV reports. Most of the film you were hunkered down in a farmhouse or a shopping mall or a remote military base. Here, you actually see cities in countries across the world going down under the ant-like swarming of the zombie hordes. It has never before been portrayed on this scale, because no one ever spent $200 million on it before.

In terms of spectacle, I think this is probably the apex. Future zombie films will not be justified just in terms of pushing the envelope of how much the effects can portray — this is about as far as you can go with that. No, future zombie films (like werewolf films or vampire films) will have to have some additional plot element or twist or gimmick. Take the venerable genre of war films. No one will likely top Saving Private Ryan in fictionally portraying war itself, but obviously war films will continue to be made. Each new war film really is a new story with war as the backdrop. What’s it like being an Explosive Ordnance Disposal specialist in war-torn Iraq? See The Hurt Locker. What’s it like hunting down and taking out one of the most notorious terrorists of our time? See Zero Dark Thirty. So what we’ll likely get, with future films, is new human stories set against the backdrop of zombie mayhem.

In terms of spectacle, I think this is probably the apex. Future zombie films will not be justified just in terms of pushing the envelope of how much the effects can portray — this is about as far as you can go with that. No, future zombie films (like werewolf films or vampire films) will have to have some additional plot element or twist or gimmick. Take the venerable genre of war films. No one will likely top Saving Private Ryan in fictionally portraying war itself, but obviously war films will continue to be made. Each new war film really is a new story with war as the backdrop. What’s it like being an Explosive Ordnance Disposal specialist in war-torn Iraq? See The Hurt Locker. What’s it like hunting down and taking out one of the most notorious terrorists of our time? See Zero Dark Thirty. So what we’ll likely get, with future films, is new human stories set against the backdrop of zombie mayhem.

As far as the adaptation question, well, anyone familiar with the book and the film knows that the book served, at best, simply as the premise from which the scriptwriters quickly departed. Part of this was practical; it is very hard to create the tension and suspense for a summer save-the-world blockbuster using the set-up of flashback interview narrative. So the U.N. reporter in the book who flew around the world interviewing over forty different survivors after the outbreak had more-or-less been brought under control is replaced in the film by Brad Pitt, a U.N. special agent who is flying around the world trying to find the cure for the outbreak in the very thick of it.

If I don’t compare the movie much to the book, I can say that it is a pretty effective zombie flick. Pitt does fine, although the subplot with his wife and daughters (to create extra pathos, because you can’t just emphasize that several billion people — over half the world’s population — has been zombified; you have to make it personal, give a human face to all those numberless masses of humanity) plays some odd notes. Ironically, even with the screenwriters inserting this family element, the sheer horror of what is happening — the threat that this may be the end of the world — does not register strongly enough with these characters. Pitt’s character Gerry Lane and his wife Karin (played by Mireille Enos) get pretty emotional about the idea of being separated while he goes to work trying to save the world, but never so much as mention the desolation of the human race they see happening before them. Maybe this is some kind of psychological survival strategy, I don’t know. But if you’re going to emphasize the inconvenience all this causes the family, maybe you can also portray some of the impact it has on people as they try to wrap their heads around the fact that this may be all, folks.

Anyway, the big set pieces — like the walls of Tel Aviv being overrun (that’s not a spoiler; they show it in the previews) — are stunning spectacle, and the film actually begins, in media res, with this edge-of-your-seat, super-size mayhem. The Lane family is actually stuck in traffic when the outbreak hits, and the first tense act of the film is all about them escaping. The quiet, small-scale, claustrophobic sneaking-past-zombies-in-tight-halls scenes come at the very end, and a few critics have issued minor complaints about this flip-flop of the usual build-up (you expect the pacing of such films to constantly increase the size of destruction until you are numbed by the pounding climax — like a fireworks show, the grand finale is where most of the money is spent). I agree with many other critics, though, who found this reversal of expectation refreshing (and kudos to Drew Goddard, who stepped in and wrote the new final act that takes place in the Cardiff, Wales World Health Organization facility. By the way, am I the only one who caught this geeky little nod: that he placed the World Health Organization [WHO] facility in Cardiff, where Dr. Who is produced?).

The film’s impact on me was quite intense at times (I should note I watched the 2d version); I felt the thrill-suspense of the big scenes, but also really appreciated the more subdued horror of some of the acts; I liked the varying of beats in the second half. The zombies in those final scenes are particularly effective — some of the best zombie make-up is combined with strangely mechanical, repetitive, jerky character motion that brilliantly conveys the unnaturalness of their altered state, altogether about as effectively as it has ever been done. The movie engaged me all the way through…

…and as I drove home down dark, wooded roads after midnight, when Billy Idol’s “Eyes Without a Face” started playing on my mix tape, it felt like the soundtrack to a haunted world.

I give World War Z (the movie) 3.5 out of 5 stars.

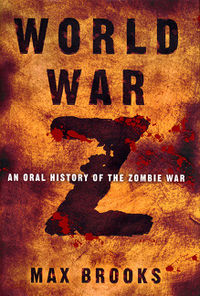

World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War by Max Brooks

Three Rivers Press (paperback reprint) (2007) $14.95

Max Brooks knows a lot about zombies, in all their incarnations from Haitian voodoo myths to George A. Romero pics. He should; he’s the author of The Zombie Survival Guide. He knows, for instance (and points out in interviews), that the undead he and Romero and all the rest are writing about and making films of these days are not zombies, historically speaking, at all; rather, they are ghouls. But this is a semantic distinction that the popular culture has largely abandoned, so I won’t belabor the point here.

Max Brooks knows a lot about zombies, in all their incarnations from Haitian voodoo myths to George A. Romero pics. He should; he’s the author of The Zombie Survival Guide. He knows, for instance (and points out in interviews), that the undead he and Romero and all the rest are writing about and making films of these days are not zombies, historically speaking, at all; rather, they are ghouls. But this is a semantic distinction that the popular culture has largely abandoned, so I won’t belabor the point here.

But Brooks also knows a good deal about global politics and international quarantine policies, and about street-level culture in Malibu, Kyoto, Tel Aviv, and a hundred other places. He knows about covert ops, extreme survival skills, martial arts, submarines, feral cats, and the ecology of whales. In short, Brooks knows a good deal about everything, and he brings all that to the table, imparting a sense that this is exactly how things would play out under the imagined circumstances. Brooks is an encyclopedia, but he never reads like one. All that knowledge informs the dialogue of his characters, helping the reader take them at their word.

The book is laid out as a series of interviews with survivors, people from all walks of life in numerous countries. Whether the stories are being told by a top-level government official or a small-time border smuggler, the voices ring true. Also, even though the stories are obviously being recounted by survivors, Brooks still manages to ratchet up nice levels of suspense and fear. What he achieves here, in sum, is truly staggering.

Of course, the event imagined cannot happen, but like all great speculative fiction, it sheds light on our own world and on events that can and may well occur. Much of what he projects the human response to be, from the neighborhood block right on up to the highest echelons of back-room government, is easily applied to a hypothetical worldwide outbreak of highly infectious disease. Thus, one can substitute any number of real global threats for the zombie menace, threats that would call for quarantine, deplete resources, and strain international relations. Brooks’s portrayal of both citizens-on-the-street and world leaders — how they react, how they survive, how they cope in the face of catastrophe and choose between courses of action that all have ethical repercussions and potentially dire consequences — could well be prescient. The obvious homework Brooks has done never overwhelms the story, but grounds it so firmly in reality that you forget how preposterous the basic premise is.

That is the power Brooks wields, and in so doing he makes, I believe, a contribution to gothic literature as powerful and as timely for the twenty-first century as Shelley’s Frankenstein, Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Stevenson’s Jekyll and Hyde were for the nineteenth or Jack Finney’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers and Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby were for the twentieth. By tapping into viable fears and present dangers, Brooks instills his imaginary bogeymen with real terror and menace. These are our worst fears given tangible form, dressed up in mythical drag: walking corpses bringing infection to our homes, invading our safe havens and reminding us viscerally with their dripping flesh and ravaged skulls that in the world we live in, there really is no such place: no haven is truly safe.

I give World War Z (the book) 5 out of 5 stars. They don’t get better than this. This is the Moby-Dick of zombie novels.

Lot of comments here to digest. I also liked the movie and would probably give it a quarter or half more star than you. It was one of the most blood-less zombie flicks I’ve ever seen (including The Walking Dead TV show). I personally appreciated that though I know most zombie-fans have poo-pooed the movie because of that.

I don’t quite share your enthusiasm for Brooks’ book though. I enjoyed it and thought it good book; but after awhile it seem to get repetitive and boring. I though about a fifth of it could’ve be removed without hurting the overall effect.

It will be interesting to see where the zombie movie will go next. There have been a few indy films that have done some very interesting things (e.g. Ponty Pool is a favorite of mine).

Thanks for the post!

Thanks James! Your observation about the relative bloodlessness of this zombie-apocalypse pic is spot-on, and has been a topic of some debate, apparently. Obviously, they did this to get the PG-13 rating, and I anticipate an Unrated Director’s Cut version when it comes to Blu-Ray.

Interesting to note, the violence is still abundant — it’s just not shown in close-up, as we’re used to with zombie flicks. One great example is when Lane whacks a zombie with a crowbar. Another zombie is coming for him, and his weapon is now lodged in the first zombie’s head. This provides a tense moment as he is trying to yank the crowbar free so he can defend himself against the next attacker. Here’s the interesting thing: the fact that the crowbar is stuck in the corpse’s cranium is never shown — it’s right off-camera, just below the frame. We know exactly what is going on, not from seeing it, but from Pitt’s actions and the accompanying sounds — and those of us who have watched our share of horror CAN picture it perfectly. It’s a case where the cues are there, so we know what is happening, but the actual gore is concealed to avoid the R rating that would turn away a large part of the summer-blockbuster target audience.

P.S. And your parenthetical note that The Walking Dead is more violent is very true and somewhat ironic: that’s what the kids are watching on their televisions at home! I’ve only seen the first few episodes of TWD, but I recall that the violence was as gruesome as anything in Romero, including zombies’ brains being splattered across the screen at point-blank range. Kind of an odd situation with the ratings system, when you think about it: if TWD were transferred from TV to the movie screen, without any modification, it would undoubtedly get an R rating.

Haven’t read the book yet, but it’s sitting here waiting. I did enjoy the movie, at least as a collection of well-created set-pieces and yes, I think this was one of the first global-scale zombie apocalypse movies. (Well, unless you count some of the later Resident Evil installments.) It was also interesting because unlike most recent treatments (Walking Dead, I’m looking at you) it was less interested in tensions between survivors than in the actual mechanics of the outbreak and shutting it down.

I’d highly recommend Mira Grant’s (penname for Seanan McGuire) Newsflesh trilogy for an interesting take on what happens after the Inevitable Zombie Apocalypse.

And I wonder if we’ll ever get an _actual_ zombie movie (Haitian voudon-style zombies as opposed to Romero-style brain-munchers) again. Time to add I Walked With a Zombie to my Netflix queue …

Call me a cynic, but since Max Brooks is the son of the great Mel Brooks, who gave us Young Frankenstein, and was himself a writer for Saturday Night Live, I can help having the sneaking suspicion that his whole zombie-writing career may be some kind of put-on. A put-on that has made him very rich! But hey, who am I to argue with success. More power to him.

John,

Given that Max Brooks also wrote the Zombie Survival Guide and does seminars on the subject complete with Q&A sessions (check him out on youtube), I don’t think there’s any veiled attempt that his zombie-writing career is NOT a “put-on” 🙂

I don’t believe Brooks’ zombie take was or is a “put-on,” but there was definitely an early element of humor involved, specifically with the Zombie Survival Guide, not so much with World War Z. I’m fairly sure Brooks made no secret of this.

Ty,

I thought John’s point was that Brooks’ career as a zombie writer is akin to his work as a humorist/comedian writer. That point seems entirely correct to me. But I don’t see this as a criticism of Brooks as a “serious” or “good” writer.

It’s clear that he can write. And though World War Z is a serious take on the zombie genre, I don’t see this as inconsistent with Brooks’ tongue being firmly in his cheek by identifying himself as a zombie writer.

Hey guys,

There’s no doubt that he can write. It’s probably in his genes. My cynical theory is this: The Zombie Survival Guide was written as a parody. It was marketed that way. I think he wrote World War Z as more of the same, but given the trend toward violent zombie movies and TV series, I think his editor said, hey, you know, what you’ve got here is a gold mine, but it’s a little gory for a parody. Why don’t we re do it as full out horror? That’s what’s trending now. I could be wrong, and it’s not a criticism. But the jump from writing a parody to “serious” horror seems weird. But like I say, if it works, go for it. I don’t begrudge any writer’s success. Maybe someday his old man will turn it into a Broadway Musical:

“Springtime for Zombies.” ; )

John Whalen,

Since there has been a live onstage Re-Animator musical, I would not be shocked to see a zombie musical, and soon. When that happens, could we safely say at that point zombies have “jumped the shark”?