Adventure on Film: The Naked Prey

Loincloths: love ’em or hate ’em, it’s a fact that Tarzan and Conan weren’t the only  musclebound men to model the style. For proof, we need look no farther than The Naked Prey (1966).

musclebound men to model the style. For proof, we need look no farther than The Naked Prey (1966).

But first, let’s time-warp back to 1980. Required reading in my junior high meant immersion in Richard Connell’s short, “The Most Dangerous Game,” in which humans are both predator and prey. It’s an old idea, but rarely presented quite as starkly as in this story, wherein a big game hunter in the Colonial tradition seeks one final thrill before hanging up his boots. As in a few Dame Agatha novels and a great many summer camp slashers, the hunter’s weekend guests become his targets.

What we teen readers were supposed to glean from “The Most Dangerous Game,” I have no idea, and I might well have forgotten the entire piece had it not been for my stumbling onto The Naked Prey a few years later. Watching this celluloid take on man hunting man transported me sharply back to the Connell story and even, if my failing memory serves, prompted me to re-read it.

In The Naked Prey, Cornel Wilde’s wily explorer-hero is actually credited as “Man.” If he has another name, we never learn it. He doesn’t really need one, although a nickname might be helpful. If I were his parent, I’d call him Determination Personified.

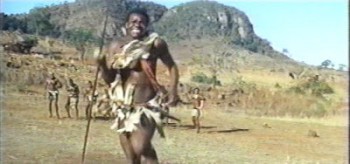

In this unlikely but effective vanity project, on which Wilde served as writer, director, producer, and star, Man’s sole object is survival. The odds against are long indeed, as Wilde’s character, one of several nineteenth century hunters on safari, runs afoul of a remote native town. The inhabitants kill Wilde’s compatriots (how they do so is downright ingenious), but give Wilde, who speaks a smattering of their language, a fighting chance. They send him off into the hills stark naked, and one by one, the town’s warriors hare after him, armed with spears. They’re expecting an easy kill.

and star, Man’s sole object is survival. The odds against are long indeed, as Wilde’s character, one of several nineteenth century hunters on safari, runs afoul of a remote native town. The inhabitants kill Wilde’s compatriots (how they do so is downright ingenious), but give Wilde, who speaks a smattering of their language, a fighting chance. They send him off into the hills stark naked, and one by one, the town’s warriors hare after him, armed with spears. They’re expecting an easy kill.

The Africans underestimate Wilde, of course. And so begins a game of cat-and-mouse through the African bush, as Man attempts to outwit and outrace Men in order to reach the fort from which he started.

Think Tarzan but more brutal.

Think Marlon Perkins’s Wild Kingdom, but with action sequences.

Think National Geographic, but in motion.

Wilde (a one-time Oscar nominee, for Best Actor in A Song To Remember) is a robust, believable hero, and a performer who never holds back. His efforts are Herculean, his exhaustion palpable. This is adventure at its most basic, an endurance test of muscle and mental focus, and it’s a final exam that I suspect many a cinematic “tough guy” would not have passed.

Wilde (a one-time Oscar nominee, for Best Actor in A Song To Remember) is a robust, believable hero, and a performer who never holds back. His efforts are Herculean, his exhaustion palpable. This is adventure at its most basic, an endurance test of muscle and mental focus, and it’s a final exam that I suspect many a cinematic “tough guy” would not have passed.

What Wilde originally set out to do was dramatize and embellish the escape of trapper John Colter from Blackfoot Indians in what was then the Nebraska Territory and is now part of Montana, not far from the headwaters of the Missouri. Colter was part of Lewis & Clarke’s cross-continental explorations, but opted to leave the main group on the way east in favor of trapping. This was risky in the extreme, as Meriwether Lewis had killed a Blackfoot man along their westward journey, and the Blackfoot nation had not forgotten.

Once captured by the Blackfoot, Colter figured he didn’t have a chance, but to his surprise, the presiding chief asked him if he was fast. Apparently satisfied with Colter’s answer, his captors stripped him and ordered him to run for his life, over a field of cacti, with a sizeable band of Blackfoot in pursuit.

Once captured by the Blackfoot, Colter figured he didn’t have a chance, but to his surprise, the presiding chief asked him if he was fast. Apparently satisfied with Colter’s answer, his captors stripped him and ordered him to run for his life, over a field of cacti, with a sizeable band of Blackfoot in pursuit.

Colter escaped, much to the surprise of all concerned. On the Criterion edition of The Naked Prey (which is what Netflix provides), there’s a handy featurette of “John Colter’s Escape,” an account penned by early Twentieth Century historian Addison Erwin Sheldon. Paul Giamatti reads the short work over Ken Burns-esque images; it’s a real eye-popper, and possibly better than the feature it accompanies. Ah, brevity.

The Naked Prey would have been made/shot in the U.S. and relied on a white man vs. Native American conflict, but somehow South Africa’s government got wind of the project, and they offered so many incentives that Wilde rewrote the film from the ground up in order to set and film the piece in Rhodesia.

It’s curious that South Africa, then at the height of its apartheid powers, should have chased after this particular project, since Wilde takes some pains to depict his pursuers as fully human. How he managed to do this in a period when the official party line prevented other working artists (among them playwright Athol Fugard and musicians Savuka and Johnny Clegg) from crossing “the color line” is a mystery the Criterion disc in no way makes clear. Nor are imdb.com and various wiki sources much help.

after this particular project, since Wilde takes some pains to depict his pursuers as fully human. How he managed to do this in a period when the official party line prevented other working artists (among them playwright Athol Fugard and musicians Savuka and Johnny Clegg) from crossing “the color line” is a mystery the Criterion disc in no way makes clear. Nor are imdb.com and various wiki sources much help.

Worse, and for all his evident generosity, Wilde himself makes enough missteps to cultivate, not alleviate, suspicion. If his character is “Man,” what does that make his pursuers? “Not Men?” The brief voice-over that concludes the film’s opening muddies the waters further:

“One hundred years ago, Africa was a vast dark unknown… The lion and the leopard hunted savagely among the huge herds of game, and man, lacking the will to understand other men, became like the beasts, and their way of life was his.”

Really? Perhaps Wilde had never heard of the great cultures of Mali, Songhai, and Ghana, but ignorance is no excuse. Certainly, history shows that Africa did not produce an industrialized culture to rival Western Europe, but does it follow that Africa’s people lacked both empathy or the will to achieve it? The voice-over’s inclusion is hugely unfortunate, in that it adds neither information nor resonance to the story at hand, and worse, its presence suggests that The Naked Prey traffics in a subtle brand of racism that makes viewing the film, for all its merits, a discomfiting experience.

Really? Perhaps Wilde had never heard of the great cultures of Mali, Songhai, and Ghana, but ignorance is no excuse. Certainly, history shows that Africa did not produce an industrialized culture to rival Western Europe, but does it follow that Africa’s people lacked both empathy or the will to achieve it? The voice-over’s inclusion is hugely unfortunate, in that it adds neither information nor resonance to the story at hand, and worse, its presence suggests that The Naked Prey traffics in a subtle brand of racism that makes viewing the film, for all its merits, a discomfiting experience.

But don’t take my word for it. Perhaps I’m barking up entirely the wrong banyan tree. See it for yourself, then check back and let me know what you think.

Mark Rigney’s latest story for Black Gate was “The Find,” which Tangent Online called “reminiscent of the old sword & sorcery classics… A must read.” You can see what all the fuss is about here.

When I was a boy, I watched this movie at my Grandfather’s house and loved it. He turns 96 years old this week, I think I’ll call him and tell him that I still remember this movie and sitting with him while watching it. Thanks for the memory!

I saw a memorable clip of this movie (where the natives kill his friends) when I was about 20 and I found it incredibly disturbing despite my Nightmare on Elm Street and Friday the 13th 80s context. Still a bit disturbing . . .

“If his character is “Man,” what does that make his pursuers? “Not Men?” ”

No, you answered it yourself a few paragraphs earlier when you wrote

“…Man attempts to outwit and outrace Men…”

He was “Man” and they were Man’s greatest enemy, “Men.”