Dion Fortune and The Demon Lover

When I took a look at Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House the other week, I did not know that February was in fact Women in Horror Recognition Month. The establishment of WiHM, as it’s abbreviated, began in 2010 as “a month-long celebration that would promote and assist underrepresented female artists while educating the public about current and past discrimination.” In 2011, WiHM was backed by the Viscera Organization, a non-profit assisting female genre filmmakers. If you want to know more, here’s the web site for the event, from which I took the foregoing quote, and the Facebook page; here’s a link to the Viscera Organization, with info on the annual film festivals they hold in Los Angeles and Boston. As for me, as a result of learning all this, I stumbled on a couple of lists of works by female horror writers. And on one of those lists, I noticed a book I’d had on my shelf for ages: The Demon Lover, by Dion Fortune.

When I took a look at Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House the other week, I did not know that February was in fact Women in Horror Recognition Month. The establishment of WiHM, as it’s abbreviated, began in 2010 as “a month-long celebration that would promote and assist underrepresented female artists while educating the public about current and past discrimination.” In 2011, WiHM was backed by the Viscera Organization, a non-profit assisting female genre filmmakers. If you want to know more, here’s the web site for the event, from which I took the foregoing quote, and the Facebook page; here’s a link to the Viscera Organization, with info on the annual film festivals they hold in Los Angeles and Boston. As for me, as a result of learning all this, I stumbled on a couple of lists of works by female horror writers. And on one of those lists, I noticed a book I’d had on my shelf for ages: The Demon Lover, by Dion Fortune.

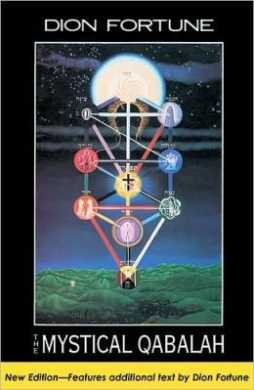

Fortune is an interesting figure. Born in Wales in or about 1890 (sources vary) as Violet Mary Firth, in her twenties she grew interested in psychotherapy and occultism — possibly a function of visions she claimed to have had since the age of four, which she came to believe were memories of a past life in ancient Atlantis; or of a nervous breakdown she suffered at age twenty, which she believed was the result of a magical attack against her. She became a Theosophist in 1914, and in 1919, while studying magic under a man named Doctor Theodore Moriarty, she took the name ‘Dion Fortune’ and joined the Order of the Golden Dawn. She founded her own magical society in 1922, the Community (later Fraternity, now Society) of the Inner Light, which aimed at bringing Chistian teachings into occultism. In 1926, she published a book of short stories based on her magic experiences: The Secrets of Dr. Taverner. The Demon Lover, her first novel, followed in 1927, with more novels coming in the years after that. She wrote several non-fiction books about occultism — I’ve read The Mystical Qabalah — although it has been argued that her novels ended up being more important for later occultists, especially Gardenerian Wiccans.

Fortune’s work certainly seems to have influenced Marion Zimmer Bradley and Diana Paxson, both as literature and as spiritual inspiration. Alan Moore has spoken highly of Fortune’s magical writing, and more equivocally ranked her with Sax Rohmer as an imaginative writer. For the sake of this piece, it may be worth noting that I’m temperamentally agnostic — I make no claim to wisdom — but naturally skeptical. I want to write about The Demon Lover because I thought it was an interesting book. Not flawless; but interesting. It’s not necessary to know, much less share, Fortune’s history and beliefs in order to enjoy the novel. But Fortune’s biography does suggest some interesting ways to look at what she wrote, and consider the relation between horror (and fantasy) and what is commonly perceived to be real.

The story of The Demon Lover begins with a secret society of mystics, in London, magically communicating over great distances with other occultists; so we learn that the society’s magic works, that it’s part of an international group, and that it’s scheming to gain political power at the urging of one member, a man named Lucas. We also see that much of the society is opposed to Lucas and his plots. This leads Lucas, after the meeting is concluded, to hatch a scheme of his own: to find an unsuspecting but psychically-gifted person to serve him as a medium, and through the entranced medium spy on the other members of the society in order to gain greater mystic knowledge.

The story of The Demon Lover begins with a secret society of mystics, in London, magically communicating over great distances with other occultists; so we learn that the society’s magic works, that it’s part of an international group, and that it’s scheming to gain political power at the urging of one member, a man named Lucas. We also see that much of the society is opposed to Lucas and his plots. This leads Lucas, after the meeting is concluded, to hatch a scheme of his own: to find an unsuspecting but psychically-gifted person to serve him as a medium, and through the entranced medium spy on the other members of the society in order to gain greater mystic knowledge.

We then shift to the perspective of young Victoria Mainwaring, a sheltered girl from the country looking for work for the summer. She applies for a secretarial post; this is actually Lucas trying to find his psychically sensitive medium. Victoria turns out to be just the person he’s looking for. He hires her, and for a while the book proceeds along much as one might expect: she’s drawn to him, but finds out his sinister purposes, tries to flee, fails, falls under the sway of his magic, and is made to serve him as medium.

But all this happens very quickly. In fact, one of the odd and involving things about the book is the way the plot keeps building and changing, but not in the way one might expect. Notionally, the incipient romance between Victoria and Lucas is the core of the book. In fact, the story comes to turn about Lucas, and his temptations toward love and power; whether he will choose to be redeemed by Victoria, and whether that redemption is even possible. That’s a standard romance idea — the female lead turning her wicked lover to the light. But there’s a bit more going on here. These two turn out to have known each other in past lives, stretching back to Atlantis. The issue of Lucas’s redemption comes to have a kind of cosmic significance. You can plausibly say that Fortune turns romance tropes to her own thematic purposes.

It is perhaps worth pointing out here that much of the supernatural machinery of the story can be traced to Fortune’s beliefs and experiences. She believed she’d had visions of past lives, like Victoria, going back to Atlantis. She entered into mediumistic trances, under the direction of male magicians. At one point Victoria’s able, without knowing it, to thwart one of Lucas’s magic spells aimed at controlling her by meditating upon a Christian prayer — and, similarly, Fortune incorporated Christian beliefs into her occult practice. Sometimes this crosses over into instances of what look like distorted autobiography: early on, Victoria tries to leave Lucas and return to her school, only to find that the school superintendant is unsympathetic to her, which seems vaguely reminiscent of Fortune’s own experience of ‘psychic assault’ from the head of a school where she was working (though Victoria’s rejection has nothing mystical about it).

It is perhaps worth pointing out here that much of the supernatural machinery of the story can be traced to Fortune’s beliefs and experiences. She believed she’d had visions of past lives, like Victoria, going back to Atlantis. She entered into mediumistic trances, under the direction of male magicians. At one point Victoria’s able, without knowing it, to thwart one of Lucas’s magic spells aimed at controlling her by meditating upon a Christian prayer — and, similarly, Fortune incorporated Christian beliefs into her occult practice. Sometimes this crosses over into instances of what look like distorted autobiography: early on, Victoria tries to leave Lucas and return to her school, only to find that the school superintendant is unsympathetic to her, which seems vaguely reminiscent of Fortune’s own experience of ‘psychic assault’ from the head of a school where she was working (though Victoria’s rejection has nothing mystical about it).

So Fortune’s use of occult themes has the practical effect of allowing her, knowingly or not, to work her own experience into the story. It also has the effect of building a credible world. The logic of magic, as described in the book, is one of its most interesting aspects: apparently coherent, it’s explained at length as necessary, but always with the implication that there’s more to be said. You can see why Fortune’s writing had an imaginative impact. And you can see how it helps the book succeed as a tale: the sense of more to know, of a limited understanding, builds the sense of horror. The narrator may be omniscient, but clearly intends to give us what we need to know and not what we might want to know. There is little reassurance. Revenant occultist-vampires may kill our children in their sleep, and we will be only incidental characters in a larger psychodrama from thousands of years before our birth. Goodness is real; so is evil.

You can read this as fantasy or horror as easily — for most people probably more easily — as you can a story based in lived experience (or ‘experience believed by the author to have been lived’). There is occasionally a sense of didactic purpose, but to me at least it felt less like preaching than the exploration of narrative rules. Which may reflect Moore’s sense of magic as a means by which to understand creativity and storytelling.

At any rate, Fortune’s less interested, I think, in what the presence of magic means for the world than she is in what magic means for the souls that encounter it. Her secret fraternities seem for the most part interested in keeping magic out of the political sphere; Lucas’s willingness to disrupt that balance marks him out as sinister. It’s weirdly like the set-up of the Harry Potter books, with a shadow-world of magic underlying everyday reality. Or you could look at it as a kind of proto-urban fantasy, with the narrative weight in unexpected places.

At any rate, Fortune’s less interested, I think, in what the presence of magic means for the world than she is in what magic means for the souls that encounter it. Her secret fraternities seem for the most part interested in keeping magic out of the political sphere; Lucas’s willingness to disrupt that balance marks him out as sinister. It’s weirdly like the set-up of the Harry Potter books, with a shadow-world of magic underlying everyday reality. Or you could look at it as a kind of proto-urban fantasy, with the narrative weight in unexpected places.

Stylistically, the book’s not terribly distinguished. You can see at a glance it’s British interwar writing, which is not necessarily a bad thing. Personally, I find that when it works, it’s syntactically elegant, if choked with semicolons and the occasional overlong paragraph. If that particular style is not to your taste, this book won’t change your mind. The effect overall is similar to David Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus or even W.H. Hodgson’s House on the Borderlands without having quite the same sense of strangeness as those works.

But the books it most reminds me of are Charles Williams’ spiritual thrillers. The style’s much the same, and they make the same use of genre plot structures to tell a story of supernatural forces interpenetrating everyday English society. Williams, in addition to being an Inkling, was also a Christian and interested in occult societies — though he joined the Fellowship of the Rosy Cross instead of the Golden Dawn. I think Fortune’s plot gets wilder than those of his stories, and is tied up more loosely, but the comparison seems reasonable to me.

It has to be said that Fortune was very much of her time. There’s a certain amount of racialist thinking in The Demon Lover — among other things, it easily assumes both that individual nationalities have specific traits and, rather more mystically, that there’s a racial consciousness or unconsciousness that acts through individuals for its own reasons. Fortune’s mysticism is also based in a certain amount of gender essentialism; so virginal Victoria can also become an icon of capital-n Nature when Fortune requires it of her. It’s not entirely surprising to find that Fortune elsewhere railed against masturbation, promiscuity, abortion, and homosexuality.

It has to be said that Fortune was very much of her time. There’s a certain amount of racialist thinking in The Demon Lover — among other things, it easily assumes both that individual nationalities have specific traits and, rather more mystically, that there’s a racial consciousness or unconsciousness that acts through individuals for its own reasons. Fortune’s mysticism is also based in a certain amount of gender essentialism; so virginal Victoria can also become an icon of capital-n Nature when Fortune requires it of her. It’s not entirely surprising to find that Fortune elsewhere railed against masturbation, promiscuity, abortion, and homosexuality.

But for all the dated attitudes and hallmarks of its time, it has to be said the book paradoxically does unexpected things. It may simply be that genre conventions weren’t as established then as they are now. But it’s a rare love story that kills off one of the lovers halfway through, and keeps on going. That inventiveness, that sense that you genuinely can’t predict what will happen next, gives the book a real interest.

And, in the end, the description of magic and mysticism succeeds narratively. Veronica’s visions as a medium and her astral voyages through outer space are surprisingly brief, but effective. Particularly since they contrast with an otherwise plain, everyday style. It’s as if even the magic is to be taken simply as a part of the fictive world: here is a motorcycle ride, here is a small-town church, here is a journey onto another plane of existence. The centre of the book’s interest isn’t quite where you think it’s going to be.

The Demon Lover is a convincingly unsettling book. Fortune evokes a world of powers that can threaten you; that are both part of a coherent moral mythology, and also cloaked in mystery. Things are unpredictable, though there is an order to them. The plot creaks at times, and the characters are flat. It’s not a book for every taste, maybe. But it’s worth a look, for a distinctive handling of magic and its overlap with the everyday world.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

The only Dion Fortune novel I’ve read is The Sea Priestess. I highly recommend it. My recollection is that the characterization is, at least sometimes, a bit richer than what you describe in The Demon Lover. The protagonist’s predicament has some unusual wrinkles, and the ending was nothing like what I expected.

Her Psychic Self-Defense handbook is considered a classic in some Neo-Pagan circles, (Also in some Neo-Pagan Circles.)

Yeah, she did seem to be trying a lot of different things in The Demon Lover, and it’d make sense if some of the creakiness I felt was simply from the fact that it was her first novel. What you say about the ending doing something you didn’t expect sounds like what I read also.

I will have to look into Psychic Self-Defense …

[…] for detail, and builds a more evocative atmosphere. Aspects of Lilith seem to prefigure things like Dion Fortune’s The Demon Lover, but the book overall lacks Fortune’s imagination and sense of drama. Corelli’s probably best […]