Genre 2013: The John Pierce Experiment

You remember John Pierce: his Bell Labs team invented the transistor, and he coined the term. But, like the rest of us, he had his little gaps. When in his eighties, he met up with author Dan Levitin, who was busy writing that complicated puzzler of a book, This Is Your Brain On Music. Much to Levitin’s dismay, Pierce revealed that he had never knowingly heard any rock music. Now, as to how one can live in a developed nation and achieve this, I don’t know, but once Levitin discovered this curious deficit, the two had a little heart-to-heart, and Pierce asked Levitin to provide six –– count ‘em, six –– prime examples of rock and roll from which he might form an opinion and make appropriate generalizations about the whole.

You remember John Pierce: his Bell Labs team invented the transistor, and he coined the term. But, like the rest of us, he had his little gaps. When in his eighties, he met up with author Dan Levitin, who was busy writing that complicated puzzler of a book, This Is Your Brain On Music. Much to Levitin’s dismay, Pierce revealed that he had never knowingly heard any rock music. Now, as to how one can live in a developed nation and achieve this, I don’t know, but once Levitin discovered this curious deficit, the two had a little heart-to-heart, and Pierce asked Levitin to provide six –– count ‘em, six –– prime examples of rock and roll from which he might form an opinion and make appropriate generalizations about the whole.

What does this have to do with Black Gate and fantasy literature? Trust me. Read on.

Levitin’s six tunes were as follows:

- “Long Tall Sally” by Little Richard

- “Roll Over Beethoven” by the Beatles

- “All Along the Watchtower,” by Jimi Hendrix

- “Wonderful Tonight,” by Eric Clapton

- “Little Red Corvette,” by Prince

- “Anarchy in the U.K.,” by the Sex Pistols

Scary choices, methinks, especially those last two. But regardless of my opinion (or yours), Pierce’s request poses two dilemmas.

First, if faced with this same conundrum, which songs would you choose?

Second, what if this situation were applied to fiction? Or better yet, to the ongoing divide in genre vs. literary fiction?

You can find my musical solution to the John Pierce Experiment at the tail end of this post, but before we get there (no skipping ahead, now), I hereby fire the opening salvo in what I shall call, in honor of Mssrs. Levitin and Pierce, the Black Gate Experiment.

You can find my musical solution to the John Pierce Experiment at the tail end of this post, but before we get there (no skipping ahead, now), I hereby fire the opening salvo in what I shall call, in honor of Mssrs. Levitin and Pierce, the Black Gate Experiment.

A word of warning: I’m going to play both sides at once. First, I’ll lay out a list of books into which all non-fantasy readers ought to sink their chompers, and then I’ll turn the tables and provide a list of six “lit” titles that all fantasy fans simply must sample.

Subjective? Definitely.

Risky? Of course.

Likely to reveal obvious gaps in my own education? Certainly.

Destined to brand me as both populist demagogue and elitist snob?

Well. One does dare, at the end of the day, to hope for compassionate treatment. Like Mr. Williams, “I have always depended upon the kindness of strangers…”

Oh, one last thing. No, two. First, I’m leaving out Tolkien and Rowling as simply too obvious. Nobody need be told about them, not even aliens from Galaxy Zero. Second, I’m including science fiction. No, that’s not up for discussion. It’s in the mix.

Oh, one last thing. No, two. First, I’m leaving out Tolkien and Rowling as simply too obvious. Nobody need be told about them, not even aliens from Galaxy Zero. Second, I’m including science fiction. No, that’s not up for discussion. It’s in the mix.

Onward, then. Let the Black Gate Experiment begin!

1. For my first title, the one with which I simply must insist all literary readers fall into bed, I give you Hyperion by Dan Simmons.

Tremendous scope, great reach. A structure born of Chaucer, with a nod to L. Frank Baum. Super prose, sharp characterizations, and an even sharper “villain,” the malevolent (?) Shrike.

As a novel, the book is composed of tales related by seven pilgrim travelers headed to the Time Tombs, located on the planet Hyperion. Each pilgrim has a personal history to recall, two of which in particular bowl me over simply on recall.

The first of these is the priest’s story, in which Father Paul Duré journeys to convert a colony of supposed primitives, only to have a “cruciform” biologically branded to his chest.

In the second of these wrenching narratives, a parent has to endure the agony of watching his daughter age backwards (she forgets him and everything she ever knew in the process).

No other rendering of time-displacement strikes such an emotional wallop. Tear-jerking does not begin to describe the emotional pitch of the writing, or the tragedy that visits that family.

2. Next up, a short story. Yep, no novel-length piece required here. Keith Roberts’s “Timothy” is perfect as is. It’s available in The Oxford Book of Fantasy Stories, and begins thus:

2. Next up, a short story. Yep, no novel-length piece required here. Keith Roberts’s “Timothy” is perfect as is. It’s available in The Oxford Book of Fantasy Stories, and begins thus:

“Anita was bored; and when she was bored odd things were liable to happen.”

In the case of “Timothy,” one odd thing takes precedence above the others, and that is Anita’s impulsive decision to bring a scarecrow to life (again, echoes of Baum) and then, against her better judgment, to befriend it.

I will not reveal what happens from there, except to say that the story poses one juggernaut question after another. It asks, as so much great writing does, what is owed? And to whom? Or in this case, what?

It’s not so much that “Timothy” makes me weep, which it does, but that it has settled in my soul. I am angry, to this day, at Anita, at her choices, and I am broken-hearted for Timothy.

What more can I ask from squiggles of black ink on an otherwise sterile page?

3. Time now to put the G in Genre with Michael Moorcock’s The War Hound and the World’s Pain.

3. Time now to put the G in Genre with Michael Moorcock’s The War Hound and the World’s Pain.

Ulrich von Bek, exhausted by his captaincy in the long debacle now known as the Thirty Years’ War, makes a deal with the devil and takes on an impossible mission: the recovery of nothing less than the Holy Grail. Armed with more muscle than brains and a penchant for grim rumination, von Bek charts a course that leads him straight out of Europe and into…where?

Moorcock’s multiverse, of course.

Moorcock stuffs this slim, trim novel with impertinent imaginings, pitched battles, and desperate escapes, all the while keeping his violent, depressive hero painfully invested in achieving a more peaceful life.

At its close, Moorcock pulls the neat theological trick of explaining God’s absence from the world while granting Lucifer a larger and even quite desirable role. The final pages also set the stage for future novels of the von Bek family, whose unlucky task it becomes to guard the Grail, and to seek it out when it becomes, as it inevitably must, lost.

4. T.H. (not to be confused with E.B.) White spent much of his reclusive life studying falconry, geese, and the natural world in general. Growing up in the wake of World War One, and writing throughout and beyond World War Two, White became fascinated by the causes of war, and what might be done to prevent it.

4. T.H. (not to be confused with E.B.) White spent much of his reclusive life studying falconry, geese, and the natural world in general. Growing up in the wake of World War One, and writing throughout and beyond World War Two, White became fascinated by the causes of war, and what might be done to prevent it.

The four-book fictional cycle that arose from his musings drops anchor in Mallory and the Arthurian cycle, and is now known as The Once and Future King. It’s a mammoth enterprise in every sense, and clearly got away from him more than once. The tone veers from slapstick comedy (as when Sir Pellinore and Sir Grummore joust) to personal, then epic tragedy (Lancelot’s faults and Arthur’s one dalliance take down an entire kingdom).

There’s magic aplenty, of course, and from all the usual suspects (Merlin, the Questing Beast, Morgause), but the heart of the book lies with Arthur himself, his almost childish desire to be loved, and his hopeless, doomed attempts to bring the world a lasting, just peace.

White was never satisfied with what he’d written. He kept going, scribbling in private, and after his death, the manuscript for a fifth volume was discovered. This devastatingly beautiful work was published in 1978 as The Book of Merlyn.

In a perfect world, it would be included within the covers of The Once and Future King, despite the repetitions of two sections, Arthur’s visits to the ant kingdoms, and then to the geese. But, publishing is as publishing does, and so the “true” conclusion of Arthur’s adventure remains unhappily separate.

To me, however, the two are forever conjoined. Read both, in order, and you will never forget the experience.

5. Dune. Fear is the mind-killer. When in combat on irregular, unfamiliar terrain, it is best to be barefoot. No debt is more important than a water debt. Never trust a mentat. Spice. Thumpers. Sand worms. The martial artistry of Gurney Halleck.

What more need be said?

6. James Tiptree, Jr., otherwise known as Alice Sheldon, doesn’t get a lot of play these days, possibly because no really ideal collection of her work has ever been assembled.

6. James Tiptree, Jr., otherwise known as Alice Sheldon, doesn’t get a lot of play these days, possibly because no really ideal collection of her work has ever been assembled.

Nevertheless, anyone seriously wanting to test the bounds of what fiction can do ought to check out Her Smoke Rose Up Forever, still in print and containing at least three of her best, “The Screwfly Solution,” “The Women Men Don’t See” and “ Houston, Houston, Do You Read?” (Smoke loses points for not including “The Dead Reef,” a terrific slice of fantastical eco-horror.)

No, there aren’t any swords or sorcerers, but there is adventure aplenty. Most of it ends badly. Consider the Odyssey of the nameless insect hero of “Love Is the Plan, the Plan Is Death,” in which self-actuality can only be achieved by dying. (In fact, come to think of it, a lot of Sheldon’s work provides epiphanies only at the moment of death.)

The remarkable energy of Sheldon’s prose and her clipped, quick dialogue more than make up for the downward spiral of her mood. Sheldon herself once mused that you could learn everything you ever needed to know about storytelling and fictional structures from reading Kipling.

For me, reading Sheldon is just about everything I need to arm-wrestle whatever story I’m up to next.

There. Six winners. Are they the best? Possibly not. And I’m sure others will have strong opinions regarding what I’ve left out. But a good beginning, surely. A fine list for our imaginary Mr. Pierce to bring to his local librarian, available Kindle, or recalcitrant Internet connection.

There. Six winners. Are they the best? Possibly not. And I’m sure others will have strong opinions regarding what I’ve left out. But a good beginning, surely. A fine list for our imaginary Mr. Pierce to bring to his local librarian, available Kindle, or recalcitrant Internet connection.

Now let’s turn the tables. Let’s bust down the genre doors and see what’s hiding in the wider, widening world…

1. I open with Little Big Man. Thomas Berger’s revisionist history of the United States’ westward expansion is not, perhaps, a better book than its non-fiction counterpart, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (by Dee Brown), but it is much funnier.

It’s also chock-full of action sequences that are as fully realized as any I can recall, regardless of style, genre, or authorial background. Our hero is Jack Crabbe, first encountered in a nursing home and purporting to be –– oh, I forget exactly, but something on the order of a hundred and twenty-four years old.

He claims to have known Sitting Bull, Wild Bill Hickock, and General George Armstrong Custer personally, and he then sets out to tell what is either the greatest whopper in the history of story, or the most remarkable narrative this side of the Pacific Coast.

Do I suspect that Anne Rice later borrowed Berger’s journalistic framing device for her Interview With the Vampire? Yes.

As an added incentive to sample this title, I happen to know that Howard Andrew Jones is also a Little Big Man fan. If that doesn’t send you rushing out to find a copy, I don’t know what will.

As an added incentive to sample this title, I happen to know that Howard Andrew Jones is also a Little Big Man fan. If that doesn’t send you rushing out to find a copy, I don’t know what will.

2. Speaking of remarkable narratives, one of the best novels of the new century is Yann Martel’s Life of Pi.

As with Little Big Man above, Pi concocts a truly incredible (as in, not really credible) tale, a shaggy woof-dog which we are asked to swallow whole. If we do, promises the author/narrator, then we will have found a story to make us believe in God.

Thanks to the recent movie adaptation, I’m sure that most of you reading this will already know that the central drama of the book is Pi Patel’s struggle, in the wake of a shipwreck, to survive sharing a single drifting lifeboat with a full-grown Bengal tiger by the name of Richard Parker.

Sound preposterous? It is. And it’s exceptional in every way.

Sound preposterous? It is. And it’s exceptional in every way.

A two-word spoiler: bananas float.

3. Not all great storytelling comes in the form of narrative prose. I’ll leave non-fiction off, just to keep the bounds of the experiment clear, but I must admit one recent dramatic work, a form that pre-dates the novel by thousands of years.

Based on the Greek myth of Orpheus losing his bride to the underworld, Sarah Ruhl’s Eurydice re-sets the original in a dreamscape of fantastic imagery and unlikely logic that sees houses built of belief and string, mail delivered between worlds by snail, and a Lord of the Underworld who travels by tricycle.

What prevents Ruhl’s delicious play from drifting away into gossamer whimsy is her pinpoint sense of loss. She wrote the play with her father’s death very much in mind, and thus Eurydice’s father becomes the third of the play’s central characters.

In Ruhl’s version of the Orpheus tale, what matters most isn’t that Orpheus loses Eurydice, it’s that Euyrdice loses her dad –– twice.

4. Jennifer Egan won the Pulitzer for A Visit From the Goon Squad, and deservedly so, but fantasy fans will want to delve instead into The Keep, in which a New Yorker on the lam flees to Europe to help his estranged cousin turn a crumbling castle into an upscale hotel.

4. Jennifer Egan won the Pulitzer for A Visit From the Goon Squad, and deservedly so, but fantasy fans will want to delve instead into The Keep, in which a New Yorker on the lam flees to Europe to help his estranged cousin turn a crumbling castle into an upscale hotel.

Egan darts in and out of fictional expectations, eventually weaving three separate yet absolutely integrated storylines into her main (or opening) plot, all the while exploring the great gothic tropes of craggy castles, haunted hallways, mysterious pools, and the terror that can take over when the lights –– all of them –– finally go out.

There’s even a modern-day dungeon crawl, in which experienced fantasy readers will find themselves all but screaming at the characters, “Don’t take the kids! Leave the kids behind! No!”

A fictional playland, The Keep. And one that should be perfect for those adventurers willing to see their fantasy-scapes enacted in the so-called “real” world. Besides, you’re going to hear more about this title: apparently Peter Weir is adapting the novel to a film… and Weir is worth his weight in celluloid gold.

5. John Irving’s shelf allotment keeps right on growing (and Irving, unlike Philip Roth, seems disinclined to retire), but it’s his earlier work that packs the greatest punch.

5. John Irving’s shelf allotment keeps right on growing (and Irving, unlike Philip Roth, seems disinclined to retire), but it’s his earlier work that packs the greatest punch.

The Hotel New Hampshire has charms aplenty, and A Prayer for Owen Meany may be the most hilarious novel I’ve ever read, but the former sprawls and the latter becomes unfortunately predictable (and in the exact same manner as Book Three of Elizabeth Moon’s Oath of Gold, where we readers are way ahead of the characters on the page).

Therefore the nod must go to The World According to Garp. Vivid characters everywhere you look, and each more eccentric than the last. Forget the movie, good though it is; read the book. Poor Garp just wants to make the world safe, for himself and those he loves, and he can’t do it.

What he can do is live, and so the novel tracks his life from birth to death, and as simple as that sounds, as innocuous as that might be for a novel’s trajectory, Garp is a page-turner from start to finish.

And guess what? It’s nearly as funny as Owen Meany.

6. War and Peace. I know, it’s a million pages long, and it’s “a classic,” and we all know from being handed far too many classics far too early (in high school and before) that the classics are drop-dead snooze-fests from cover to misbegotten cover.

6. War and Peace. I know, it’s a million pages long, and it’s “a classic,” and we all know from being handed far too many classics far too early (in high school and before) that the classics are drop-dead snooze-fests from cover to misbegotten cover.

But actually, that sort of collective wisdom (or jaundice) is wrong-headed. We owe it to ourselves to shake free of those pedagogical memories and move forward, boldly, Kirk-like. (Ooh. Did I just write that? Zounds.)

My point is that a vast number of the so-called classics are brilliant works of art, and not one of them looms so large as War and Peace. Yes, it sprawls, but sprawl, with sufficient artistry, can be a virtue. Consider Kutusov’s musings about when it became necessary to surrender Moscow to Napoleon.

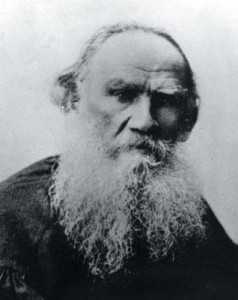

In my own life, these inform and infuse so much of what I write that I don’t know where I’d be without him. (Note to self: thank Tolstoy again tonight, when I see the Bearded One in my dreams.) Pierre and Natasha are indelible. The descriptions of the battles (the war in War) are precise and darkly comic. And in peace? Wedding bells will ring, but will they ring for the right couples?

My only caveat here: the opening chapter is a bear (presumably Russian). Tolstoy has no interest in making it easy to meet his thousand and one Moscow party guests. But once the reader trudges through this thickly populated, clotted opening, the Russian world is spread, with beauty and intelligence, at your waiting feet.

There.

The experiment is ended. Go in peace.

Or better yet, tell me where I’ve gone wrong. And where you, gentle reader, would go right.

(Postscript: for my own solutions to Levitin’s original John Pierce Experiment, please visit my Anti-Blog via this handy-dandy LINK.)

Mark Rigney’s latest story for Black Gate was “The Trade,” which Tangent Online called a “marvelous tale.” You can see what all the fuss is about here.

Mark, this is a wonderful post and I’m going to do it a tremendous disservice by ignoring almost all of it in order to ask you the obvious, Rock(nRoll)-headed question…

What the heck did Pierce think of those songs?! Is there any record of his reaction?

I went to your blog and devoured the entire post, seething with questions about the hows and whys of your choices and, especially, why some bands/songs didn’t seem to track on your radar and why others seemed to loom so large.

And now something I never thought I’d write…

I gotta go find that Meatloaf tune on Youtube.

John – Well now, where to begin…

First, THIS IS YOUR BRAIN ON MUSIC does describe a few of Pierce’s reactions, which were mostly positive, and mostly focused on structure and musical interplay, not artistic value. Or at least that’s my distant memory.

Second, good luck with the Meatloaf.

Third, stop! This is supposed to be a post about fantasy literature!

: )

M

The question you ask is too large to fit into a flip response. I will say that Silverlock (John Myers Myers IIRC) is as perfect a melding of fantasy and mythology that you will ever see. Microcosmic God by Sturgeon is everything you need in an SF story, short, to the point and leaving you with a sense of “what happens next”.

All that being said, Jim Steinman is a brilliant song writer and I know all the lyrics to “I’m a stranger here” (since 5MEB gets air play on oldies stations in Canada).

Hmmm, both stories I mentioned are from the 40s…

I should read more.

I am thrilled to discover another human being who remembers “I’m a Stranger Here.” Now I need to go back and brush up on my Sturgeon…

I’m a Canadian who’ve lived in the US since 1987, and I can tell you honestly I haven’t heard The Five Man Electrical Band on the radio in roughly 25 years… and I STILL remember the lyrics to “I’m a Stranger Here.” Mostly.

It’s very peculiar. I thought I was posting a piece about writing, but in fact I was simply fanning the flames of a collective latent love for the Five Man Electrical Band. I guess I should have seen the SIGNS a little sooner.

The first half of your proposal is a fresh exercise in canon formation. When it’s impossible to be comprehensive or definitive, what do you shoot for? I’m going to shoot for making the list too fast to second-guess myself.

List of SF/F books for the mainstream-only reader:

1) A Wizard of Earthsea, Ursula Le Guin. (The perfect illustration of fantasy’s ability to illuminate our own inner lives.)

2) The Dispossessed, Ursula Le Guin. (If you want to introduce the lit-reader with no genre background to both science fiction and fantasy, handing them one classic on each side of the divide, both by the same author, can show both the breadth of the field’s possibilities and why we talk about SF/F in the same breath in the first place. Plus, structurally brilliant, touching, and funny.)

3) The Gods of Pegana, Lord Dunsany. (The high style so many writers have tried to imitate is one of Dunsany’s natural voices. It rolls effortlessly along the page, edging subtly into satire, tragedy, philosophy, and kickass action, somehow simultaneously baroque and understated.)

4) A Song of Ice and Fire, George R.R. Martin. (Yes, the whole series, even the volumes that aren’t written yet. Multivolume Big Fat Fantasy is one of the main lineages within SF/F, and with Martin, you get a bonus exemplar of the gritty, cynical mode.)

5) Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon, Spider Robinson. (For humor, warmth, and the linked short story collection)

6) Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, Susanna Clarke. (For sheer intoxicating glory, for fun, for a world in which magic is as real as scientists so magicians are driven in the same range of ways as scientists are, and to represent the alternate history lineage.)

The second list is harder. Looking at your proposed six books, you seem to be both looking for books categorized as mainstream that push the same joy-buttons that SF/F does for its fans, and looking for books that exemplify forms of excellence that are as different as possible from the forms common in SF/F. I’m just going to keep typing and see what comes out:

1) Mrs. Dalloway, Virginia Woolf. (How we fantasy readers love our fantasy cities! Woolf engages is masterful worldbuilding to bring us Mrs. Dalloway’s London, when she really could have gotten away with not doing that. When I started writing in my Beltresa setting, I stole tricks and techniques from this book very deliberately, all the time.)

2) One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel Garcia Marquez. (For lovers of dynastic epics complete with genealogies. Also for bursts of inner and outer wonder, revealed through luminous, dreamlike details.)

3) Vineland, Thomas Pynchon. (For globe-sprawling intersections of conspiracy and coincidence, and for a constant conjoining truly noble struggle with slapstick satire.)

4) Motherless Brooklyn, Jonathan Lethem. (Low-level career criminal with Tourette’s syndrome sets out to solve the mystery of a friend’s murder. Wacky, tragic, breathtaking, hilarious hijinks ensue. Lethem makes me want to be a better writer.)

5)Invisible Cities, Italo Calvino. (More high literary than mainstream, aggressively postmodern, lyrically beautiful, and irresistible to any writer who engages self-consciously in worldbuilding.)

6) The Woman Warrior, Maxine Hong Kingston. (A collection of parts, each part of which is part essay, part short story, and part myth. Kingston writes about how we all grow up awash in stories, and how we shape ourselves in response to those stories. Her central ancestral story is that of Fa Mu Lan, the kickass legendary female general of ancient China. The women warriors of SF/F owe a great deal to Hong Kingston’s Fa Mu Lan, but not many readers in the genres know this book.)

And that was my attempt to be brief! Oh well. But I couldn’t just throw the titles out there and not think aloud about them.

The typos, oh my, the typos. Wish there were an option to edit that reply.

Sarah wins an award for not mentioning the Five Man Electrical Band. This must have taken great strength and courage.

THE DISPOSSESSED nearly made my list. Inches off.

I’m not familiar with JONATHAN STRANGE; I’ll have to look into that.

As for the “lit” list, ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE was also a near miss, and I nearly threw on THE BARON IN THE TREES from Calvino (although IF ON A WINTER’S NIGHT A TRAVELER… is probably the better book, and his ITALIAN FOLKTALES is like reading fairy tales from Planet X).

Pynchon: I staggered through CRYING OF LOT 49, and still wonder what I was supposed to get from it, i.e., the nature of the author’s intent. I do know that Pynchon suggests I abandon the U.S. Mail, but the internet seems to be doing that all by itself.

Kingston: I know the name, not the book. My reading list expands apace.

Who else has work to suggest to me, John Pierce, or the world?

Sarah, I just promoted you to editor in WordPress. You should now see an option to edit your comments.

And look — I didn’t even mention The Five Man Electrical Band.

Thank you, John!

It seems to me I ought to let out a supervillain laugh, go power-mad and… and… I actually can’t think of anything dastardly to do with my newfound powers, except possibly mention The Five Man Electrical Band. Who were those guys, anyway?

Sarah,

Use your powers only for good. Like, listening to “Signs” and “I’m a Stranger Here.”