DeMatteis and Muth’s Moonshadow

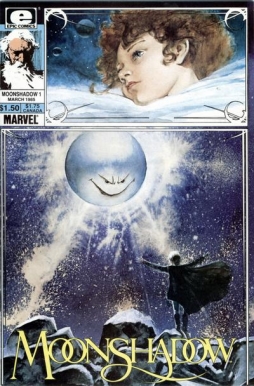

There was a time in the 1980s when it looked like Marvel and DC Comics might slowly evolve into something like mainstream book publishers: publishers who gave creators fair deals respecting copyright, and who lived off of the publication of new titles rather than the exploitation of intellectual property from decades previous. That hasn’t really happened, so far as I can see. Both companies dabbled in various kinds of creator ownership, but both appear mostly to have retreated to the relative safety of work-for-hire deals in recent years. Vertigo, a DC imprint featuring better deals for creators, seems to have become more strict in their contracts, and the recent departure of their founding editor doesn’t seem promising for the imprint’s future. Epic, Marvel’s attempt at a creator-owned line, largely faded away in the 1990s (though Marvel does still occasionally do some creator-owned work through their Icon imprint). Before it died, though, Epic published what might have been the best comic series in the 1980s to be printed with a Marvel Comics logo, up there with Walt Simonson’s run on Thor: J. M. DeMatteis and Jon J. Muth’s twelve-issue series Moonshadow. Later reprinted by Vertigo, with a slightly changed conclusion, Dematteis and Muth also created a sequel, Farewell, Moonshadow, now reprinted along with the original series in a paperback collection of the whole work, The Compleat Moonshadow. It’s a weird, heady mix of science fiction and fantasy, of fairy tale and scabrous parody. I want to talk a bit about it here.

There was a time in the 1980s when it looked like Marvel and DC Comics might slowly evolve into something like mainstream book publishers: publishers who gave creators fair deals respecting copyright, and who lived off of the publication of new titles rather than the exploitation of intellectual property from decades previous. That hasn’t really happened, so far as I can see. Both companies dabbled in various kinds of creator ownership, but both appear mostly to have retreated to the relative safety of work-for-hire deals in recent years. Vertigo, a DC imprint featuring better deals for creators, seems to have become more strict in their contracts, and the recent departure of their founding editor doesn’t seem promising for the imprint’s future. Epic, Marvel’s attempt at a creator-owned line, largely faded away in the 1990s (though Marvel does still occasionally do some creator-owned work through their Icon imprint). Before it died, though, Epic published what might have been the best comic series in the 1980s to be printed with a Marvel Comics logo, up there with Walt Simonson’s run on Thor: J. M. DeMatteis and Jon J. Muth’s twelve-issue series Moonshadow. Later reprinted by Vertigo, with a slightly changed conclusion, Dematteis and Muth also created a sequel, Farewell, Moonshadow, now reprinted along with the original series in a paperback collection of the whole work, The Compleat Moonshadow. It’s a weird, heady mix of science fiction and fantasy, of fairy tale and scabrous parody. I want to talk a bit about it here.

Moonshadow is a curious coming-of-age story. A hippie named Sunflower is abducted from Earth by smirking balls of light called G’l Doses, who have the power of gods and utterly inscrutable motives; one of them impregnates her, and their child’s named Moonshadow by his mother. The book is his story, told by an aged Moonshadow recalling his youth. He remembers his growing up in the G’l Doses’ ‘zoo’ before his exile in company of his mother, his cat, and a faceless furry humanoid named Ira who’s all id: sex drive and scatology. They kick around the universe, and Moonshadow becomes orphan and outcast; alternately soldier and nanny, confidant of kings and outcast untouchable. He grows older, encounters sex and death and things of the spirit. It’s picaresque on a grand scale, the plot loose, characters fading in and out, recurring and being abandoned.

Stylistically, the book has a distinctive tone of jaded romanticism. Young Moonshadow’s a naïf; old Moonshadow is world-weary, and almost obsessively undercuts his younger self’s ideals. Oddly, the insistence on a not-entirely-convincing pose of cynicism is perhaps the most adolescent thing in the book. What strikes truest is the book’s depiction of a universe full of the purely unpredictable; wonder, horror, crassness, and all those things that cannot be known. The feel of the work is more fantastic than science-fictional, more dreamlike than either. Moonshadow takes place in a kind of Carollian Wonderverse, where a sinister funeral home director can be the son of an éminence grise with a planetary king wrapped around his finger. It’s wild, wholly unlikely, and a bit of a glorious mess. Which is why it works; the point of the setting is not to be convincing, but to let the story stumble through a range of tones and references and emotions, and in that it succeeds.

Stylistically, the book has a distinctive tone of jaded romanticism. Young Moonshadow’s a naïf; old Moonshadow is world-weary, and almost obsessively undercuts his younger self’s ideals. Oddly, the insistence on a not-entirely-convincing pose of cynicism is perhaps the most adolescent thing in the book. What strikes truest is the book’s depiction of a universe full of the purely unpredictable; wonder, horror, crassness, and all those things that cannot be known. The feel of the work is more fantastic than science-fictional, more dreamlike than either. Moonshadow takes place in a kind of Carollian Wonderverse, where a sinister funeral home director can be the son of an éminence grise with a planetary king wrapped around his finger. It’s wild, wholly unlikely, and a bit of a glorious mess. Which is why it works; the point of the setting is not to be convincing, but to let the story stumble through a range of tones and references and emotions, and in that it succeeds.

Writer J.M. DeMatteis has had one of the most diverse careers of any writer I can think of. He broke in at DC Comics in the late 70s, and moved to Marvel in the 80s; he was writing fairly standard superhero stories with a bit more literacy than usual, a bit more heart, if a tendency also to new-age mysticism. The original graphic novel Greenberg the Vampire came out in 1985, the same year Moonshadow began. Both books seem to me tremendous steps forward for him as a writer. He followed them in 1987 with Blood: A Tale (and also worth noting here is his 1986 Doctor Strange graphic novel Into Shambhalla), but also returned to mainstream comics. He wrote perhaps the most acclaimed Spider-Man story of the last twenty-five years, Kraven’s Last Hunt, then moved over to DC, where his relaunch of their venerable Justice League of America title as Justice League International added surprisingly effective humour to the super-hero formula, producing perhaps the most memorable run in the book’s history. He’s continued to write both super-hero adventure — he’s just been announced as the new co-writer on DC’s Phantom Stranger title — and more personal work, including the excellent semi-autobiographical Brooklyn Dreams and the children’s book Abadazad. (His artistic collaborators for the foregoing: Mark Badger on Greenberg, Kent Williams on Blood, Dan Green on Shambhalla, Mike Zeck on Kraven’s Last Hunt, Keith Giffen, Kevin Maguire, and Ty Templeton on JLI, Glenn Barr on Brooklyn Dreams, and Mike Ploog on Abadazad.)

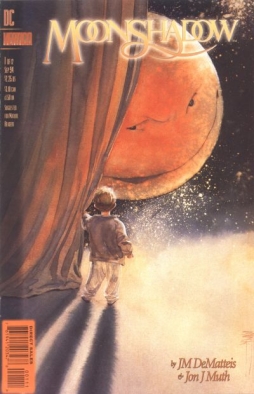

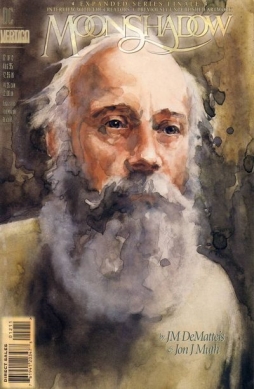

Jon J. Muth was only 25 when Moonshadow began. As far as I can tell, it was his first major comics work. He went on do a graphic novel in 1986, Dracula: A Symphony in Moonlight, and then various other comics over the next dozen or so years, ranging from a Wolverine mini-series (Havok & Wolverine: Meltdown, with writers Louise and Walter Simonson and artistic collaborator Kent Williams), to an adaptation of Fritz Lang’s screenplay for M, to an original graphic novel written by Grant Morrison (The Mystery Play). About a dozen years ago he moved from comics to children’s books, illustrating Karen Hesse’s 1999 Come On, Rain. He’s collaborated with a number of writers since then, and written several of his own children’s books; his 2006 Zen Shorts was shortlisted for the Caldecott Medal.

Jon J. Muth was only 25 when Moonshadow began. As far as I can tell, it was his first major comics work. He went on do a graphic novel in 1986, Dracula: A Symphony in Moonlight, and then various other comics over the next dozen or so years, ranging from a Wolverine mini-series (Havok & Wolverine: Meltdown, with writers Louise and Walter Simonson and artistic collaborator Kent Williams), to an adaptation of Fritz Lang’s screenplay for M, to an original graphic novel written by Grant Morrison (The Mystery Play). About a dozen years ago he moved from comics to children’s books, illustrating Karen Hesse’s 1999 Come On, Rain. He’s collaborated with a number of writers since then, and written several of his own children’s books; his 2006 Zen Shorts was shortlisted for the Caldecott Medal.

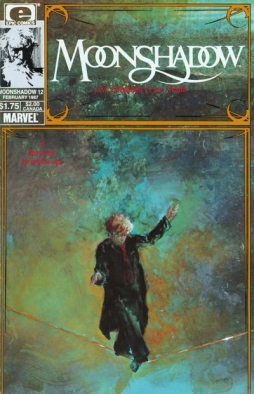

Muth’s painted artwork ably matches the strangeness of the script. His work seems to be mostly watercolours, with some added detail drawn over it. It’s simultaneously highly realistic and wildly exaggerated, precise and freewheeling. Muth’s sense of character design is impeccable, creating weird caricatures that turn to be capable of surprisingly wide and subtle ranges of emotion. His Ira is instantly recognisable: a biped all-over hair, a bowler hat perched above his featureless face, always smoking something, somehow disreputable, bedraggled, and filthy, stinking just by the look of him.

Muth blends realism and cartooniness in the same panel, sometimes even the same figure, and makes it work. His backgrounds tend to be mostly expressionistic, sometimes perhaps too much so; on occasion one loses the sense of figures acting in a defined three-dimensional space. But then the idea of a world of mist is symbolic within the story; and I think the background haziness often helps to bring out the dreamlike air.

Muth blends realism and cartooniness in the same panel, sometimes even the same figure, and makes it work. His backgrounds tend to be mostly expressionistic, sometimes perhaps too much so; on occasion one loses the sense of figures acting in a defined three-dimensional space. But then the idea of a world of mist is symbolic within the story; and I think the background haziness often helps to bring out the dreamlike air.

The storytelling’s effective, if not overly complicated. Panels are large, the pages frequently dominated by a central image, or else designed around strata of full-width images. A few years ago, there was a vogue for ‘widescreen’ comics, comics where the panels mimicked the aspect ratio of blockbuster films — Moonshadow is an early example from well before the phrase was coined, though it’s much more of an art-house piece. The individual images are frequently fairly static, with DeMatteis’ narration nicely-placed in dead areas (the lettering here is by Kevin Nowlan, an accomplished artist himself). Occasionally, this tends to make the story read like illustrated prose, but the good moments outweigh the bad. The creators select powerful images, and every so often Muth will pull out a loose, cartoony sequence of panels, varying the approach nicely.

I wonder if this was a case where the conditions of the original publication affected the telling of the story. Not necessarily in a dramatic way, where some outside censorship or editorial dictate changed the way things were going. It seems to me that the technique seems to grow smoother as the book goes, more assured, and I wonder if the fact that the book was published over the course of a year allowed Muth to grow artistically as he was working on it. This is a lot of pages for a young artist, and very accomplished pages. Visually, it’s a treat.

I wonder if this was a case where the conditions of the original publication affected the telling of the story. Not necessarily in a dramatic way, where some outside censorship or editorial dictate changed the way things were going. It seems to me that the technique seems to grow smoother as the book goes, more assured, and I wonder if the fact that the book was published over the course of a year allowed Muth to grow artistically as he was working on it. This is a lot of pages for a young artist, and very accomplished pages. Visually, it’s a treat.

DeMatteis’s writing is excellent as well. He fuses all sorts of influences in his story and makes it work; it’s both highly romantic and a critique of the romantic, both whimsical and profound, profane and yet reaching for the spiritual. Since the story’s told mostly through narration, rather than dialogue or detailed action, it’s less dramatic than dreamlike. The surreal nature of the setting adds to that feel. So does the overall structure of the tale, an archetypal coming-of-age yarn, an unpredictable bildungsroman. Moonshadow as a youth is an everyman, or more precisely an everyboy on the cusp of becoming an everyman. The older Moonshadow looking back on his life is a distinct, individualised personality and storyteller. That’s not so much true of his younger self, or of most of the other characters. They’re less individuals than they are dream-images, symbols of the unconscious. As such, they mostly work.

Ira, Moonshadow’s comrade, is probably the most rounded of the other characters. So much so that it’s debateable whether Moonshadow’s view of him, and the overall drama of the book, really hits home. Ira’s so abusive and exploitative early on that key sections later in the story, which require us to accept that he has some value to a variety of other characters, are difficult to swallow. But then again, one of the themes of the book is Moonshadow’s spiritual growth, his learning to value everyone he meets, even the most brutal. To an extent, the dramatic role Ira takes on forces the reader to mimic that awareness that Moonshadow develops. It may be true that for all his sympathetic moments, Ira’s still a vicious, tedious character; but if the book works, then by the time it concludes, at least while you’re reading it, you come to understand that every character has value, even a wretch like him.

Ira, Moonshadow’s comrade, is probably the most rounded of the other characters. So much so that it’s debateable whether Moonshadow’s view of him, and the overall drama of the book, really hits home. Ira’s so abusive and exploitative early on that key sections later in the story, which require us to accept that he has some value to a variety of other characters, are difficult to swallow. But then again, one of the themes of the book is Moonshadow’s spiritual growth, his learning to value everyone he meets, even the most brutal. To an extent, the dramatic role Ira takes on forces the reader to mimic that awareness that Moonshadow develops. It may be true that for all his sympathetic moments, Ira’s still a vicious, tedious character; but if the book works, then by the time it concludes, at least while you’re reading it, you come to understand that every character has value, even a wretch like him.

And speaking of that conclusion: the book was revised when it was reprinted in 1994 by Vertigo, adding text to a concluding visionary passage. What was originally studied anticlimax becomes more guided, more explicit in its coming-of-age resolution. I’m divided about whether the change works or not. The action is certainly clearer in the new version, and it’s easier to understand what Moonshadow’s feeling. But I’m not sure that’s entirely positive. Sometimes it’s better to let the reader connect the dots, even if they might make connections the creators didn’t intend. And in general, I feel the book often works best when it’s least defined; when the elder Moonshadow admits that he doesn’t understand why things happened the way they did, why people do what they do. When actions are simply depicted, their motives left to the reader’s imagination; when paradox is accepted. The new conclusion is more dramatically coherent, but perhaps less effective, less ambiguous and bittersweet. The tonal range feels less varied, and for a book that stands out in part because of the range of tones it manages, that’s a real loss.

The paradox of the book’s effect as a whole is that moments of high emotion or drama — Moonshadow’s near-death, Ira’s recovery from having his spirit broken, even Sunflower’s early passing — are less effective than the overall sense of a dream unfolding. But it doesn’t have the flatness of dream, instead feeling involving and even taut. The tightness isn’t the sense of standard narrative craft or highly-machined structure, but of involvement. Of true storytelling. Some of that may be a function of the sheer extravagance of imagination from both creators. Some of that is how the imagination’s deployed, how the variety of influences and tones are worked into a single coherent tale. Either way, it’s effective. I don’t honestly know if Moonshadow would be to everyone’s tastes. But those for whom it works, I think, will love it.

The paradox of the book’s effect as a whole is that moments of high emotion or drama — Moonshadow’s near-death, Ira’s recovery from having his spirit broken, even Sunflower’s early passing — are less effective than the overall sense of a dream unfolding. But it doesn’t have the flatness of dream, instead feeling involving and even taut. The tightness isn’t the sense of standard narrative craft or highly-machined structure, but of involvement. Of true storytelling. Some of that may be a function of the sheer extravagance of imagination from both creators. Some of that is how the imagination’s deployed, how the variety of influences and tones are worked into a single coherent tale. Either way, it’s effective. I don’t honestly know if Moonshadow would be to everyone’s tastes. But those for whom it works, I think, will love it.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

[…] DeMatteis and Jon J. Muth’s Moonshadow so powerful. I don’t know if I wholly succeeded. Judge for yourself here. Filed under: Uncategorized Comment […]

I was never a big fan of DeMatteis’ writing (IIRC, he wrote Marvel’s oddest superhero team book – Defenders – for a time, but then pretty much everyone had trouble following Stever Gerber’s run on that). I’d probably appreciate his writing a lot more nowadays, though – I suspect I missed subtleties at the time.

In mentioning Marvel work of the 80s, though… I can only jump up and down pointing to Peter David’s run on “The Incredible Hulk”, which for me was the best (at least up until the end of the Pantheon storyline). That combined so many elements – pathos, humor, intelligence, all without sacrificing the staple Hulk diet of action – that it remains, for me, a masterclass in handling character.

Matthew,

Another fine pick. I remember MOONSHADOW well — it was a huge series for Epic, and incredibly ambitious at the time (12 issues, when most mini-series were a bare 4). I was smitten with Jon J. Muth’s watercolors, too.

What I remember most about it, though, was that it was veeery slow moving. I eventually stopped reading the individual issues and just bought the collected set when it inevitably appeared.

And I never even knew about Farewell, Moonshadow. Thanks for the tip!

I remember reading Moonshadow as it came out and found it to be a very interesting on one hand but slower than molasis on the other. Then about ten years later I re-read it and found that everything clicked and that it was one terrific graphic novel. Sometimes a work of fiction just doesn’t lend itself to serialization. Is the revised ending very extensive? I’m just wondering whether it would worth getting in trade.

tchernabyelo: DeMatteis is such a hit-or-miss writer. When he’s on, he’s brilliant. When he’s not … well … let’s say, he produces stuff that doesn’t really suggest what he’s capable of. Defenders is a case in point, I think; if I remember right, that was some of his early Marvel work. Some decent stories, as I recall, but nothing like Moonshadow.

Good point about the Peter David Hulk, too. It’s not quite my cup of tea, but definitely one of Marvel’s better books. For what it’s worth I do tend to think of it as belonging to the 1990s — inaccurately, since according to the Grand Comics Database David started on the book in early 1987, writing it through to 1998.

John: It’s interesting you and Randy both mention the pace of the original series. I bought it for the first time as a trade paperback of the Epic run, and I didn’t feel it was slow at all. But then again, it does read much more like a single coherent work than most miniseries from that time do. And relies on creating a certain mood, too. As I think it over … I can see how dividing the book into twelfths would make it a much different, and much slower, experience.

Randy: As I said to John, I think you’re right about the difference serialisation makes here. The revisions to the ending aren’t that extensive; there’s that one extended vision near the end, in the last issue, which in the new version has captions added to it in which Moonshadow tells us what he’s thinking and feeling. So on its own not much. But I gather the current trade also includes Farewell, Moonshadow. That’s fairly extensive, something like 64 pages. So if you’re thinking of upgrading to a trade anyway, it’s worth doing. Probably not worth it just for that, though.

[…] Dematteis and Muth’s Moonshadow […]