I’ll Look Down and Whisper “No”: “Before Watchmen”

Last Wednesday, DC Comics announced a new publishing venture: “Before Watchmen,” a set of related miniseries that would act as a prologue to the best-selling and critically acclaimed Watchmen graphic novel. The news was met with a considerably mixed reaction. Alan Moore, writer and primary creator of Watchmen, has spoken out against the project. Personally, I’m not going to buy any of DC’s new series, and I want to explain why.

Last Wednesday, DC Comics announced a new publishing venture: “Before Watchmen,” a set of related miniseries that would act as a prologue to the best-selling and critically acclaimed Watchmen graphic novel. The news was met with a considerably mixed reaction. Alan Moore, writer and primary creator of Watchmen, has spoken out against the project. Personally, I’m not going to buy any of DC’s new series, and I want to explain why.

First, some more details. From The Beat website, a list of titles and creators:

– Rorschach (4 issues) – Writer: Brian Azzarello. Artist: Lee Bermejo

– Minutemen (6 issues) – Writer/Artist: Darwyn Cooke

– Comedian (6 issues) – Writer: Brian Azzarello. Artist: J.G. Jones

– Dr. Manhattan (4 issues) – Writer: J. Michael Straczynski. Artist: Adam Hughes

– Nite Owl (4 issues) – Writer: J. Michael Straczynski. Artists: Andy and Joe Kubert

– Ozymandias (6 issues) – Writer: Len Wein. Artist: Jae Lee

– Silk Spectre (4 issues) – Writer: Darwyn Cooke. Artist: Amanda Conner

“Before Watchmen” starts sometime this summer, with one comic to be released per week. Each book will have a two-page back-up feature, “The Curse of the Crimson Corsair,” written by Wein, who edited the original Watchmen, with art by John Higgins, who coloured the series. An epilogue featuring a number of writers and artists will wrap up the event.

On the whole, this is a fairly impressive line-up, particularly in terms of the artists. But it’s fair to say, I think, that none of these creators have ever produced anything even near the power of Watchmen. Few people have. And the impression is inevitable that Len Wein, a veteran mainstream comics writer but not at this point a name that normally drives sales, was included in the project due to his connection to the original series. “Because if Citizen Kane had had a prequel, Orson Welles’ editor should’ve written it,” sniped one commenter.

On the whole, this is a fairly impressive line-up, particularly in terms of the artists. But it’s fair to say, I think, that none of these creators have ever produced anything even near the power of Watchmen. Few people have. And the impression is inevitable that Len Wein, a veteran mainstream comics writer but not at this point a name that normally drives sales, was included in the project due to his connection to the original series. “Because if Citizen Kane had had a prequel, Orson Welles’ editor should’ve written it,” sniped one commenter.

From another angle, blogger J. Caleb Mozzocco found it odd that these artists would be assigned to this project: “Adam Hughes interior work? You’re wasting that on four of the 34 Watchmen prequels, instead of having him finish All-Star Wonder Woman, or an original miniseries? You just relaunched your entire superhero line in order to attract new readers to your comics, and you have Amanda Conner drawing a prequel to a 26-year-old comic book series that no one really wants to exist anyway?”

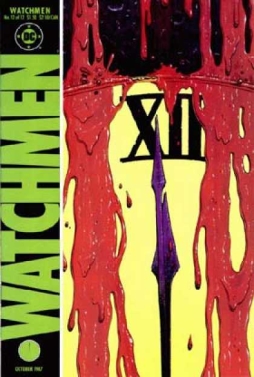

A number of people noted that the original series was twelve issues long, whereas thirty-five issues of “Before Watchmen” have been announced. Is the market there for this volume of material? DC clearly think so; the collection of the original Watchmen series is their best-selling graphic novel, having sold, by some estimates, four million copies. Still, there is skepticism about the creative value of the new titles, and it’s not hard to see why.

To explain this skepticism, I’m going to try to outline something of the context in which the original book was published, then look at the qualities of the book itself, and finally discuss the issues of creators’ rights that the book raised then and now.

To explain this skepticism, I’m going to try to outline something of the context in which the original book was published, then look at the qualities of the book itself, and finally discuss the issues of creators’ rights that the book raised then and now.

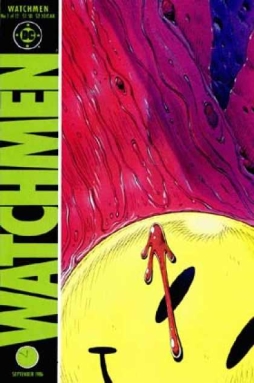

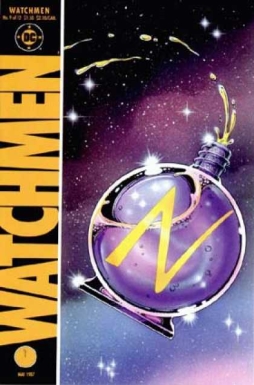

The original Watchmen was published from September 1986 through October 1987 (it was scheduled as a monthly, but its last issues were delayed). At the time, comics’ then-new Direct Market — dedicated comics stores — had helped foster a wave of new talent and new approaches to the artform, mostly emerging from small presses and self-publishers: The Hernandez Brothers’ Love & Rockets, Dave Sim’s Cerebus, Scott McCloud’s Zot!, Howard Chaykin’s American Flagg, and many others. These books pioneered new approaches to comics, new techniques and new structures. Not only creatively, either. Traditionally, the comics mainstream in North America had focused on super-hero stories produced under work-done-for-hire agreements; the creators did not maintain copyright or control over their creations. The new marketplace and new publishers seemed to be leading to a sea change, perhaps to an industry closer to prose publishing, where authors maintained their copyrights.

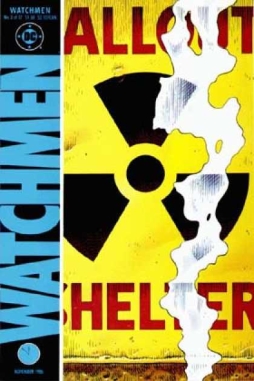

1986 saw a “black-and-white-explosion,” when independent comics, typically produced without interior colour artwork, became a collectible craze. At the same time, comics were reached a new height of critical acclaim, buoyed principally by three works: Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Returns, art spiegelman’s Maus, and Watchmen. In that moment, it seemed that those three works in particular suggested new creative possibilities for comics, and represented new heights of craft and art. In the years since, I think Dark Knight’s come to be seen as something of a product of its era — a well-done book, but not at the level of the other two works. Watchmen, by contrast, has only become more revered over time.

Why? What sets it apart from Dark Knight? What does it do that few other comics have done, before or since?

Why? What sets it apart from Dark Knight? What does it do that few other comics have done, before or since?

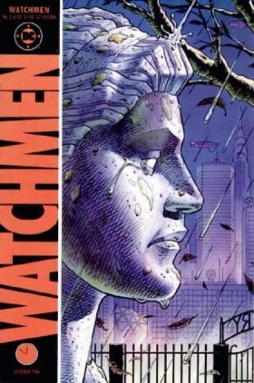

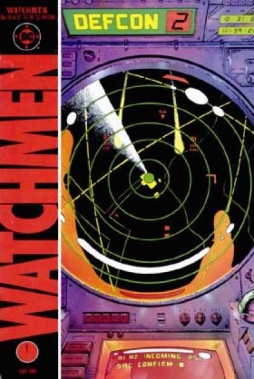

The story’s set in a world where super-heroes, mostly normal men and women with acrobatic or martial-arts skills, began to appear around the time of the Second World War. One genuine super-human, Doctor Manhattan, appeared in the 1950s, significantly changing the way the world developed. In the 70s, legislation was passed in the US outlawing super-heroes. In 1986, with Richard Nixon still president, someone begins murdering the retired heroes. The mystery surrounding the deaths leads into a vast and chilling conspiracy; it also leads into more personal mysteries, as the tale skips back and forth in time to build up its characters and their backgrounds.

Watchmen’s a narratively dense and formally dextrous tale about super-heroes, a post-modern analysis of the genre, interrogating traditional narrative devices and questioning accepted conventions. It’s structurally complex, a crystalline or fractal story in which every minor verbal or visual detail links up to every other detail not only in terms of plot but theme. Moore and Gibbons use puns, allusions, and a web of references to tie together the imagery of the book; most notably, the recurring shape of the iconic smiley-face with a splash of blood over its left eye — a subversion of mindless optimism and 80s consumerism.

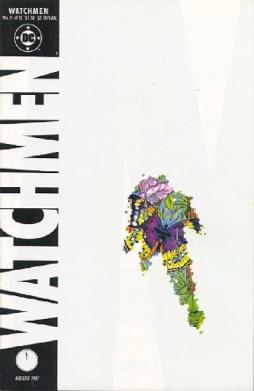

On the one hand, Watchmen’s a work of flawless technique. You can use it to explain to people who’ve never read comics in their life how the form works and what’s remarkable about it. Or you could teach it at a graduate-level comics course, going through it panel-by-panel, unpacking allusions and linkages.

On the other hand, and what may be most impressive, despite the battery of formal tricks Moore and Gibbons use, it’s a very human book. That’s fitting, since a part of the thematic core of the book is the value of humanity, the worth of the human individual, and the human capacity for overcoming fear to reach out to others. But more than that: the characters live and feel like real people, with real capacities for error and greatness. Real contradictions, real hopes, real fears.

The book was acclaimed as a masterpiece when it came out — in fact, even as it came out. From the first issue it was apparent that the book was unlike anything else on the stands. In 1986, it seemed to be pointing the way to some new future in terms of the sophistication of its content — and in terms of creators’ rights. Moore noted in several interviews that the contract he and Gibbons had signed would ensure that the rights to the work would revert back to them in a year or two after the book was done.

The book was acclaimed as a masterpiece when it came out — in fact, even as it came out. From the first issue it was apparent that the book was unlike anything else on the stands. In 1986, it seemed to be pointing the way to some new future in terms of the sophistication of its content — and in terms of creators’ rights. Moore noted in several interviews that the contract he and Gibbons had signed would ensure that the rights to the work would revert back to them in a year or two after the book was done.

That didn’t happen.

The wording of the contract seems to have specified that the rights would revert to the creators once Watchmen went out of print. At the time, comics went out of print as a matter of course. Trade paperback collections of series or storylines were extremely uncommon — Marvel had collected the “Dark Phoenix” storyline from their Uncanny X-Men title and the “Demon in a Bottle” storyline from Iron Man, but I’m not sure DC had ever done any collections. Watchmen, and the collection of Moore’s other book V For Vendetta, were two of their first. Big sellers from the start, those books never went out of print. Moore has therefore never regained the rights to the series and characters.

This is the essence of the ethical issue surrounding Watchmen (and V): Moore and DC had an agreement that Moore at least believed was supposed to lead to a certain outcome, but due to the wording of the contract embodying the agreement, DC was legally able to not follow through. Other irritants emerged. DC allegedly was able to get out of paying Moore and Gibbons a cut of the proceeds from the sale of certain Watchmen merchandise by labelling the merchandise as “promotional items.” More seriously, DC planned to impose an age-ratings code on comics similar to the age ratings on films; Moore and other creators opposed this policy. In 1989, Moore ceased writing for DC.

(Several years later, DC bought a comics company, WildStorm, for which Moore had created an imprint called America’s Best Comics; it appears that the purchase was motivated at least in part by the chance to acquire the ABC line. Moore fulfilled his contractual obligations, and his obligation to his collaborators at ABC, and then left again. WildStorm was founded and sold to DC by Jim Lee, now DC’s co-publisher, and one of the men who approved “Before Watchmen.”)

(Several years later, DC bought a comics company, WildStorm, for which Moore had created an imprint called America’s Best Comics; it appears that the purchase was motivated at least in part by the chance to acquire the ABC line. Moore fulfilled his contractual obligations, and his obligation to his collaborators at ABC, and then left again. WildStorm was founded and sold to DC by Jim Lee, now DC’s co-publisher, and one of the men who approved “Before Watchmen.”)

For over twenty years since Moore left DC, the company refrained from aggressively exploiting Watchmen. It’s been suggested that Paul Levitz, DC’s former president, acted as a kind of guardian of the book, preventing its exploitation. Levitz stepped down as president in 2009, coincidentally the same year a film of Watchmen was released.

With Levitz gone, suspicions grew that prequel or sequel series would be authorised. Moore said in a 2010 interview with Wired that:

They offered me the rights to Watchmen back, if I would agree to some dopey prequels and sequels… So I just told them that if they said that 10 years ago, when I asked them for that, then yeah it might have worked. But these days I don’t want Watchmen back. Certainly, I don’t want it back under those kinds of terms.

I don’t even have a copy of Watchmen in the house anymore… The comics world has lots of unpleasant connections, when I think back over it, many of them to do with Watchmen.

More recently, the comics rumour site Bleedingcool.com published several art samples it said were from an upcoming “Watchmen 2” project. The publication of the art was met with cease-and-desist letters from DC, an unusual step. Last Wednesday, news of the prequels became official.

DC quoted Gibbons, who never had the public falling-out with the company that Moore did, as follows:

The original series of Watchmen is the complete story that Alan Moore and I wanted to tell… However, I appreciate DC’s reasons for this initiative and the wish of the artists and writers involved to pay tribute to our work. May these new additions have the success they desire.

Some have seen this statement as a rather tepid blessing at best. Moore, by contrast, has been very direct. In an interview with the New York Times he called the project “completely shameless” and noted that “I tend to take this latest development as a kind of eager confirmation that they are still apparently dependent on ideas that I had 25 years ago.” He said that he intended no legal action, believing that DC would fight such action with an “infinite battery of lawyers,” but noted that “I don’t want money … What I want is for this not to happen.”

While some fans and industry figures met the announcement of “Before Watchmen” with enthusiasm, many others were more muted in their reaction, and a number were openly contemptuous. There was much doubt about the creative worth of the new project: Watchmen’s a self-contained work, and one of the greatest accomplishments in the medium, so what is the artistic point of a series of prequels not done by the original creators? Granted that many of the people involved in these series have done good work on their own, why not hire them to create new material?

While some fans and industry figures met the announcement of “Before Watchmen” with enthusiasm, many others were more muted in their reaction, and a number were openly contemptuous. There was much doubt about the creative worth of the new project: Watchmen’s a self-contained work, and one of the greatest accomplishments in the medium, so what is the artistic point of a series of prequels not done by the original creators? Granted that many of the people involved in these series have done good work on their own, why not hire them to create new material?

Presumably, DC thinks “Before Watchman” is a more lucrative use of these creators. It is true that the current anglophone North American comics market is relatively hostile to new work, and tends to respond to existing properties — when DC relaunched their entire line with 52 new titles a few months ago, every single title was a continuation of an ongoing story, a reboot of an existing comic, or an extension of a previous franchise. Certainly, given Moore’s choice not to mount a legal challenge, DC has the legal right to publish these sequels. The ethics, though, are less clear-cut.

As noted, the mainstream American comics industry has a terrible track record on creative rights. At the same time, this specific situation — where a creator believes he was promised rights that he was legally tricked out of, and has called for derivative works not to be published — is fairly unusual. Jack Kirby, for example, clashed with Marvel over the company’s return of his original artwork, but so far as I know never suggested that other people should stop writing and drawing his creations.

Numerous creators over time have argued that they did not know what rights they were signing away to publishers, pointing to the vague state of early work-for-hire agreements. Until the late 70s, creators apparently often didn’t sign contracts; companies stamped a waiver on the back of freelancers’ paychecks, so that when the freelancers endorsed the checks to cash them, they were “signing” a work-for-hire agreement. Several legal challenges have since been mounted against the practice in attempts by the creators to recover ownership of the characters, though the courts have tended to find for the companies; a couple of months ago, for example, Ghost Rider creator Gary Friedrich lost a case over rights to the character, a case which Friedrich intends to appeal. Still, Moore’s situation is different from these. His belief was that he and DC had reached a good-faith agreement on who should have what rights, only for DC to find a loophole in the contractual language which deprived Moore of the rights he believed were his.

Numerous creators over time have argued that they did not know what rights they were signing away to publishers, pointing to the vague state of early work-for-hire agreements. Until the late 70s, creators apparently often didn’t sign contracts; companies stamped a waiver on the back of freelancers’ paychecks, so that when the freelancers endorsed the checks to cash them, they were “signing” a work-for-hire agreement. Several legal challenges have since been mounted against the practice in attempts by the creators to recover ownership of the characters, though the courts have tended to find for the companies; a couple of months ago, for example, Ghost Rider creator Gary Friedrich lost a case over rights to the character, a case which Friedrich intends to appeal. Still, Moore’s situation is different from these. His belief was that he and DC had reached a good-faith agreement on who should have what rights, only for DC to find a loophole in the contractual language which deprived Moore of the rights he believed were his.

Moore’s outspokenness also seems unusual. Perhaps the closest equivalent to his case in that respect is Steve Gerber. Gerber, who wrote for Marvel Comics in the 1970s, created a number of characters and titles; the most relevant here are Howard the Duck and Omega the Unknown. Howard began as a walk-on gag character, who gained his own series and developed into a satirical mouthpiece for Gerber’s views. When conflicts developed between Gerber and Marvel, Gerber was removed from the book and from the newspaper strip spun off from the book. Gerber launched a lawsuit, which was settled out of court in 1985; terms of the settlement were not made public, though Gerber did return to writing for Marvel. At the time, and up to his death in 2008, Gerber was outspoken in his belief that Howard was an unusually personal creation (for mainstream comics) that other writers did not fully grasp, and did not write as well as he did; most readers agree.

Gerber, with Mary Skrenes, also created the title Omega the Unknown for Marvel in 1976. It ran for 10 issues before being cancelled. In 2007 a 10-issue re-imagining of Omega was published by Marvel, written by novelist Jonathan Lethem, a childhood fan of the original. Gerber was unhappy with the existence of the revival, and said so. (It’s also been suggested that who owns the character is less than clear.)

I bought Lethem’s Omega the Unknown. I now think I was wrong to do so. Gerber, the co-creator of the character, clearly and forcefully expressed his disapproval of the revival. If the mainstream comics industry extended the same rights to creators as is normal in prose fiction, he would have had the right either to prevent the publication of the revival, to work with Lethem himself, or indeed to finish the story as he and Skrenes had intended. And Moore would have the right to prevent “Before Watchmen.”

I bought Lethem’s Omega the Unknown. I now think I was wrong to do so. Gerber, the co-creator of the character, clearly and forcefully expressed his disapproval of the revival. If the mainstream comics industry extended the same rights to creators as is normal in prose fiction, he would have had the right either to prevent the publication of the revival, to work with Lethem himself, or indeed to finish the story as he and Skrenes had intended. And Moore would have the right to prevent “Before Watchmen.”

Some have argued that the morality of the Watchmen case is muddied by Moore’s own use of other writers’ creations. His books Lost Girls and League of Extraordinary Gentlemen drew heavily on pre-existing literary figures. Watchmen itself had its genesis when DC asked Moore to re-imagine a set of characters originally published by Charlton Comics, whose rights had now been acquired by DC. Moore’s initial proposals led DC to ask Moore to develop his own characters. If Watchmen was based in the Charlton characters, the argument runs, does Moore have any moral standing to talk about them as his own creations?

I think so. I think the Watchmen characters are at least as distinct from the Charlton characters as Superman is from Doc Savage and from Philip Wylie’s Gladiator, two acknowledged influences on the character. Or, if you prefer, as different as Batman is from Zorro or The Shadow. New stories are always inspired by old ones.

On the other hand, rights to a character or story don’t exist forever. The characters Moore uses in LOEG have fallen into the public domain. They’re available for anyone to use. And the writers who created them knew this would happen after their death. I see no contradiction here with Moore’s stance. (Moore has made reference in LOEG to some characters still under copyright; so far as I know, these uses are fundamentally satirical, which is allowed.)

On the other hand, rights to a character or story don’t exist forever. The characters Moore uses in LOEG have fallen into the public domain. They’re available for anyone to use. And the writers who created them knew this would happen after their death. I see no contradiction here with Moore’s stance. (Moore has made reference in LOEG to some characters still under copyright; so far as I know, these uses are fundamentally satirical, which is allowed.)

At least some of the creators of the sequels have thought about the moral issues involved with the work. J. Michael Straczynski said in an interview that:

A lot of folks feel that these characters shouldn’t be touched by anyone other than Alan, and while that’s absolutely understandable on an emotional level, it’s deeply flawed on a logical level. Based on durability and recognition, one could make the argument that Superman is the greatest comics character ever created. But neither Alan nor anyone else has ever suggested that no one other than Shuster and Siegel should ever be allowed to write Superman. Alan didn’t pass on being brought on to write Swamp Thing, a seminal comics character created by Len Wein, and he did a terrific job. He didn’t say “No, no, I can’t, that’s Len’s character.” Nor should he have.

… Alan has spent most of the last decade writing some very, very good stories about characters created by other writers, including Alice (from Wonderland), Dorothy (from Oz), Wendy (from Peter Pan), as well as Captain Nemo, the Invisible Man, Jekyll and Hyde and Professor Moriarty. I think one loses a little of the moral high ground to say, “I can write characters created by Jules Verne, HG Wells, Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Conan Doyle and Frank Baum, but it’s wrong for anyone else to write my characters.”

The lack of his blessings has no more impact on the actual storytelling process than would be the case if we had his blessings. The story has to stand on its own. A crappy story wouldn’t be helped by having his blessings, and a good one isn’t made better for it. Would it be nice? Sure. I’d love it. Again, I have always been a massive fan of Alan’s work. Back when I worked on The New Twilight Zone, I tracked him down and, after pulling every string I could find, managed to get him on the phone to ask if he’d please consider writing an episode. (He said no.) Alan is the best of us. I’ve said repeatedly, online and at conventions, that on a scale from 1-10, Alan is a full-blown 10. I’ve not only said it, more importantly, I’ve always believed it.

Pressed further by fans, Straczynski reflected in a post on Facebook about the prequel project. He said:

Let me start out by tackling head-on the most frequent question: “how would you feel if Babylon 5 was being done without your permission?” It’s a fair question, and it needs to be fairly answered… but it has to be an honest comparison, apples to apples, not apples to pomegranates.

First, we have to take the word “permission” off the table. Warner Bros. owns Babylon 5 lock, stock and phased-plasma guns, just as DC owns the Watchmen characters. DC wasn’t making creator-owned deals back in the 80s. Moreover, they were variations on characters that had been previously created for the Charleton Comics universe. Main point is: neither of us owns these characters in any significant legal way. Consequently, neither company needs our permission to do anything.

Straczynski went on to note that DC had approached Moore over the years with various offers to continue the work, and said:

If Warners offered me creative freedom, money and a budget to do the show the way I wanted, up to and including my completely owning the show, and I said no to that deal, and if after Warners waited TWENTY FIVE YEARS for me to change my mind they finally decided to go ahead and make B5 without me… then I would have absolutely zero right to complain about it. Because it was my choice to remove myself from the process, it wasn’t something foisted upon me by anybody else.

I think Straczynski’s assessment is misleading in several respects; most significant, probably, is the fact that Moore clearly believed that DC was offering him a kind of creator-owned deal. Comics writer, publisher, and former DC editor Mark Waid, responding to a report on the Comic Book Resources website of Straczynski’s statement, had this to say:

I find it absolutely impossible to believe that DC, at any point, offered Alan “anything he wanted” as financial compensation, much less “complete creative freedom.” I’m sure they offered him boatloads of cash and I’m sure they offered him “creative freedom within reason,” but JMS is overstating in order to make a better case for his side. Also, in trying to “balance” the comparisons, JMS forgot to add the qualifier, “Let’s also say that, without getting into whether I was right to believe so or just crazy, I believed to my absolute core that the company who was trying to woo me back to Babylon 5 was a corporation who had (in my opinion) already screwed me repeatedly and who I could never in a million years bring myself to trust to deal fairly and morally with me despite contractual language in my favor.”

None of what I have just said is intended to take sides or to especially bolster Alan’s side or to snipe at JMS… but as someone who was on staff during Watchmen’s original publication and first-hand witness to the many growing problems between Alan and DC, I can tell you that it’s a very thorny, very complex situation in which (IMO) both sides have valid reasons to believe that the other doesn’t deal fairly or sanely. I bring this up only because I bristle at JMS’s assertion that what he offers is a “more accurate” analysis of the overall mess instead of an equally flawed restacking of the deck.

(It may or may not be relevant, but Waid and Straczynski recently clashed over a post by Straczynski which purported to show declining sales on Amazing Spider-Man after Straczynski left that title as writer, to be replaced by a group which included Waid.)

For me, personally, the whole “Before Watchmen” situation is nicely summed-up in this blog post from the publisher of Image comics, Eric Stephenson:

For me, personally, the whole “Before Watchmen” situation is nicely summed-up in this blog post from the publisher of Image comics, Eric Stephenson:

It was a dirty deal, and the fact that there are people who want to rationalize it by saying, “Well, Alan Moore wrote League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and Lost Girls, and those books used other writers’s characters, so how is this any different?” just shows that truth is a sadly devalued currency. It’s different because Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons negotiated, in good faith, a deal that would have allowed them to retain the rights to Watchmen.

And yes, the characters in Watchmen were inspired by characters like Peacemaker, Thunderbolt and The Question. We know that, because Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons told us as much. Had they kept that inspiration quiet – would anyone anywhere have mistaken Watchmen for something published by Charlton Comics? Dr. Manhattan is no more the same character as Captain Atom as Captain Marvel is Superman or Blue Beetle is Spider-Man.

All in all, it’s a strange double standard, arbitrarily applied to an amazing writer who has done more than almost anyone else to draw serious attention to this medium. And it’s one that anyone who supports creator’s rights should find fairly troubling, if not outright maddening.

I think that’s an accurate assessment, and I strongly recommend reading Stephenson’s full post. To put things in further context, consider the following quote from Darwyn Cooke, who’ll be working on two of the titles:

I’d consider [Watchmen] a masterpiece if it had been able to have found what I would refer to as a hopeful note. … Again, it’s not hard to understand [where Alan was coming from], and that sort of storytelling does have an allure for young people. [But] I think the older you get, the more you look for hope or positive things. Maybe I’m just getting old.

So there’s one of the creators of the prequels saying that he disagrees with the basic themes of the original story. Cooke went on to say that his Silk Spectre series “is probably going to be the most hopeful of all the books.” It is of course appropriate for a creator to bring their own beliefs and perspective to a project, and appropriate to enter into dialogue with significant works in the tradition of which their own creations are a part. But for me, personally, it feels wrong for a creator to have their consciously revisionist approach to a classic work published as an authorised part of the story.

I won’t be buying “Before Watchmen.” Frankly, I’m going to think at least two or three times before buying work by any of the creators involved in the future. In fairness, not everyone approached for the prequels agreed to take part. According to Bleedingcool.com, Kevin Smith has said:

Talked to Jim [Lee] and Dan [DiDio] about it two years ago. Only passed because I’m not Alan Moore, sadly. If I was Alan Moore, I’d be all over it. As Kevin Smith, I’d likely just make Bubastis “big pussy” jokes and have Rorschach wet himself. Hurm.

Make of that what you will.

Personally, I think the great irony here is that if not for DC’s own actions, further Moore-written Watchmen material might have already been produced. Moore himself spoke of the possibility of writing prequels while in the early days of the original project. In fact, Moore-authorised prequels, of a sort, actually already exist. During the series’ publication Moore worked with the people at Mayfair Games, who at the time published a licensed DC Heroes role-playing game, to produce two Watchmen role-playing supplements (two more were later produced after Moore left DC). It’s clear that Moore was at one point open to further investigation of the story. DC’s approach to business alienated him.

As late as 1987, Moore produced a proposal for a massive crossover event to be called The Twilight of the Superheroes. Elements of the proposal have turned up in other DC projects over the years, perhaps most notably Waid and Alex Ross’ Kingdom Come miniseries. Still, it’s difficult to calculate how well an Alan Moore-written crossover series would have sold for DC in 1988 (and over the years since). It’s quite possible to argue that in pursuit of short-term profit, DC deprived themselves of real long-term gain. It would be a kind of poetic justice, I suppose, and I can’t help but want to find any kind of justice in what is, in the end, a fairly squalid situation.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Excellent, well-considered article.

I did go and see the movie (and enjoyed it for what it was; a reimagining of Moore’s work by a less deft but enthusiastic hand) but I doubt I’ll be taking any notice of these books.

Truly a well considered article. I think that if a generation of artists are going to work in this world, this group is as good as any. Most people under 25 have a difficult time “getting” The Watchmen. While the general themes remain fresh (fascism, determinism, religion etc.), The time is fast-approaching when new readers will have no frame of reference for Thatcherism, Perestroika or what it was like to grow up under the threat of global thermonuclear war. This may be the last generation of artists who have something to say about the specific aspects of The Watchmen.

If it’s ethical or not, I don’t know, but I am kind of curious from an historical perspective. Will these prequels have the same oppressive atmosphere that the originals had? Will they provide the same level of social commentary? How can they?

A fine article, Matthew.

I have to admit I sympathize to some extent with DC in this case, however. (And in the related case of the V FOR VENDETTA trade paperback, which is part of the larger story of Moore’s relationship with DC).

DC is a business. I don’t think you can really blame it for earning money off its properties. That’s what businesses do. In the larger context, I don’t really believe what DC is doing does any real harm to Alan Moore, or diminishes his accomplishment with WATCHMEN.

Now, I think Alan Moore was treated very poorly by DC in regards to WATCHMEN, and especially with V FOR VENDETTA, which Moore and David Lloyd created for the British comic WARRIOR in 1982, six years before DC reprinted it. Even setting aside moral considerations, this was a terribly short-sighted business decision by DC — Moore vowed to never work for them again as a result.

Considering that WATCHMEN and V FOR VENDETTA have consistently been two of DCs top-selling graphic novels for more than two decades, it’s obvious that DC shot itself in the foot. They could have had dozens of hot properties, instead of just milking those two for 25 years.

But. No one forced Alan Moore to sign the contracts for WATCHMEN and V FOR VENDETTA. He took the money up front, and DC bet on the long-term sales. DC won that bet. Rather than turn around and blame DC for the terms of a contract HE AGREED TO when he signed it, I think Moore would have been much smarter to be a better negotiator with his next contracts.

I’ve signed plenty of bad contracts in my day. You learn from them and accept your mistakes, not blame the other party and simply refuse to play any more. The sad truth is that Moore had alienated himself from so many of the major publishers (Marvel, DC, Image, etc.) as a result of bad business deals by the end of his career that he was virtually unpublishable. And that’s a damn shame.

Thanks for the good words, everyone.

John, I agree that the prequels probably won’t literally hurt Moore, though emotionally it’s got to be rough knowing people are willing to jump in and work on something you think of as your own stuff, while dismissing your own experiences. I certainly agree they won’t hurt the original; most likely they’ll fade away over time.

But I do think it’s appropriate to blame a business for displaying a lack of ethics when they behave unethically. “Trying to make money” isn’t a get-out-of-civilized-behaviour-free card.

Again, from what I gather — and I have to go by Moore’s account, since so far as I know, nobody from DC at the time’s really spoken about it — Moore believed he had a deal with DC, and the contract was a recognition of the deal. At the very least, he said as much in public. Somebody at DC could have told him if he was wrong. Certainly I think it’s unreasonable for him to expect that DC would invent a new publishing format.

I mean, I don’t know whether DC was planning the trade paperback collection at the time they signed the contract, or whether they realised that putting a collection together would give them an out from the contract, or indeed whether they made plans for the publication and then realised that the language of the contract would benefit them (though I think the last one’s unlikely). But that’s what happened, and if they’d chosen to take the long view and make things right, they could have. The issue of the money’s beside the point, I think; that doesn’t seem to be what Moore’s upset about. He’s been pretty consistent in talking about creator’s rights, a huge issue back in the 80s.

Simply moving on from a bad contract is one option, I guess, but I don’t see what’s wrong with blaming the other party when they do something blameworthy. I’d disagree that Moore’s near the end of his career — he’s only in his 50s, and if he’s been silent lately, it’s because he’s been working on two major projects, a 600 000-word novel and a history of western occultism (while putting out his own magazine, Dodgem Logic). Certainly he’s not unpublishable. I mean, I don’t think he’s alienated himself from Image (Rob Liefeld personally, maybe, but not Image that I know of). And he had no problem getting publishers, and press, for his last ventures — Neonomicon from Avatar, Lost Girls and LOEG from Top Shelf (with Knockabout Productions). I’m gonna bet that if he chooses to put his novel up for auction when he’s finished with it, he’ll have no problem finding takers.

Actually, he’s been with Top Shelf quite a while now. I look back over his career, and it really looks to me as though his disagreements with comics publishers are a function of the comics marketplace. The assumption that creators own their works, a pretty basic principle in prose, was nonexistent in mainstream comics when Moore started working there. Hopefully he’s found himself a better situation, in a more mature field — one he helped to create.

Yep, John, I’d echo Matthew there – Alan Moore’s problems with DC date back not to the existence of the contracts, but (from hs perspective) DC’s desire to twist/break those contracts, which he sees as unethical. He chose not to sign any more contracts with DC because he didn’t trust them to keep their word, and knew that they had far more legal resource to fight then he ever would.

I met him, many years ago when he was only a big name in the UK (when he was doing Marvelman and V for Vendetta and Captain Britain), and he left a huge impresson on me. Charming, honest, erudite, passionate, and without a hint of pretension (he may seem weird but believe me he’s totally genuine). The man is and will always remain a legend – a God – in the comics field.