Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Mars, Part 1: A Princess of Mars

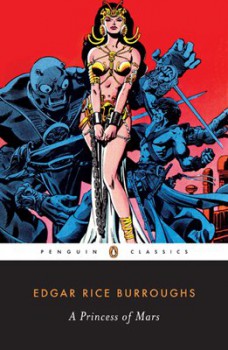

The year 2012 C.E. is the centenary of the Reader Revolution. Two novels published in pulp magazines that year, A Princess of Mars and Tarzan of the Apes, re-shaped popular fiction, helped change the United States into a nation of readers, and created the professional fiction writer. One man wrote both books: Edgar Rice Burroughs.

The year 2012 C.E. is the centenary of the Reader Revolution. Two novels published in pulp magazines that year, A Princess of Mars and Tarzan of the Apes, re-shaped popular fiction, helped change the United States into a nation of readers, and created the professional fiction writer. One man wrote both books: Edgar Rice Burroughs.

In celebration of this anniversary, and in anticipation of the upcoming Andrew Stanton film John Carter based on A Princess of Mars, I will tackle all eleven of ERB’s Martian/Barsoom novels in reviews for Black Gate. I also have something special in store for Tarzan of the Apes. This endeavor sounds a touch insane, but come on, but this is the centennial of the series! When else am I going to do it?

Let us turn back the calendar a hundred years to the beginning of all things…

Our Saga: The adventures of Earthman John Carter, his progeny, and sundry other natives and visitors, on the planet Mars. A dry and slowly dying world, the planet known to its inhabitants as “Barsoom” contains four different human civilizations, one non-human one, a scattering of science among swashbuckling, and a plethora of religions, mystery cities, and strange beasts. The series spans 1912 to 1964 with eleven books: nine novels, a book of linked novellas, and a volume collecting two unrelated novellas.

Today’s Installment: A Princess of Mars (1912)

The Backstory

In 1911, Edgar Rice Burroughs was thirty-five years old and selling pencil sharpeners out of an office in Chicago. His post-military service career was so far a series of undistinguished jobs that kept him and his family barely above poverty: an associate in a mining company in Idaho, a railroad policeman in Salt Lake City, a manager of a stenography department, an owner of a stationery store, and a partner in an advertising agency. No position lasted longer than two years.

Burroughs spent part of his time at the pencil sharpener office scanning the company’s ads in the pulp magazines. In a moment of frustration with his whole life, Burroughs decided to write a better story than the drivel running in the rough paper pages. He started writing down a daydream on the backs of old letterheads during breaks at the office. He finished the book, an adventure on Mars inspired by the popular theories of astronomer Percival Lowell, while at his next job, working in a stationery manufacturing company. He sent the first part of the manuscript to editor Thomas Newell Metcalf at Frank A. Munsey’s Company, and after re-writing and negotiating, he received $400 to have it serialized under the pseudonym “Norman Bean.” (Originally “Normal Bean,” but a copyeditor caught the “mistake” and fixed it.)

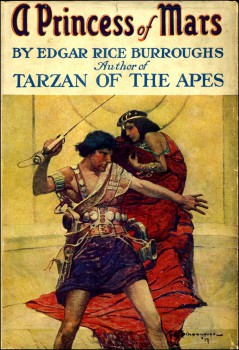

This first novel appeared in serial form as Under the Moons of Mars (a name often used for the “John Carter Trilogy” that fills the first three books) in Munsey’s All-Story, February-July 1912. When A. C. McClurg published it in hardcover in 1917, the name changed to A Princess of Mars, and thus do we know it today.

The public loved it. A career was born, and science fiction (a term not even in existence yet) took a leap into grandiose, outrageous adventure. At the end of the year, All-Story ran Tarzan of the Apes complete in one issue, and Edgar Rice Burroughs, impoverished stationery salesman and failed miner, suddenly emerged as the most popular living American writer.

The Story

The Story

This novel inaugurates the tradition of opening with a prologue featuring a fictional version of Edgar Rice Burroughs, who states he was five years old before the start of the Civil War. (The real Burroughs was born in 1875.) Pseudo-ERB explains how he came upon the incredible manuscript which follows: it was the property of his uncle John Carter of Virginia, who disappeared for a decade but came back seemingly un-aged. After Carter was found lying dead in the snow, ERB took possession of the manuscript, but only now — twenty years after its author’s death — can he at last release John Carter’s personal account of his astonishing adventure…

After the conclusion of the Civil War, Captain John Carter of Virginia seeks his fortune in a gold hunt in the hills of Arizona. After a run-in with Apaches, he takes shelter in a cave. Through an unknown property of the cave, Carter leaves his corporeal body and is able to project himself to the bright red mark of Mars in the night sky. (Astrally? Magically? Teleportation? Yes?)

Carter discovers the lower gravity of the planet gives him immense leaping prowess and relatively increased strength. He also possesses a telepathic power allowing him to catch other telepathic messages, while remaining unreadable to others.

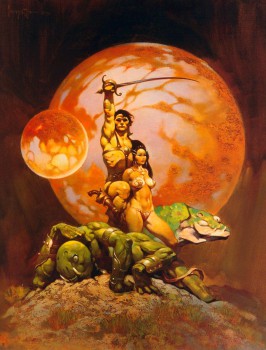

Soon after his arrival, Carter falls into the clutches of the green Martians, fierce fifteen-foot multi-limbed warriors. When attempting an escape, Carter slays two of the giant white apes of Mars and earns the loyalty of his “watchdog” Woola, a creature called a calot. Under the kind care of the female Sola, the captive earthman begins to learn the language of the Tharks, the tribe of green Martians who captured him.

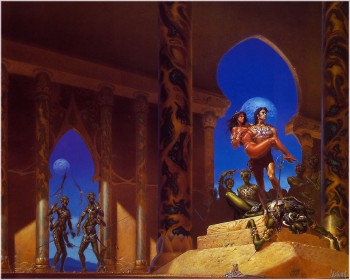

Carter encounters another Martian race, humans with a coppery skin color known as the red men, when the Tharks down one of their floating skiffs. Carter gets his first glimpse at the lovely Dejah Thoris, Princess of the city of Helium (who is also completely naked, to the delight of adolescent boys in 1912). When Carter strikes down a Thark who attacks Dejah Thoris in the plaza before an audience, he earns the respect of the other Tharks, particularly vice-chieftain Tars Tarkas, and gains rank among them. But John Carter is already planning his escape with Dejah Thoris.

Carter recognizes he is in love with the Martian woman, but through the “communication errors” that would become a Burroughs’s trademark, she at first resists him. When the tribe marches to the city of Thark, where the cruel Tal Hajus is jeddak (emperor), Carter must hatch a quick scheme to escape before the jeddak executes him and Dejah Thoris. He receives the help of Sola, whose mother died at Tal Hajus’s hands because she would not reveal her secret lover. Sola tells John Carter that her father is none other than Tar Tarkas, something the Thark warrior does not even know.

John Carter and the two women manage to escape the city, but he valiantly lets the green men recapture him so Dejah Thoris and Sola may slip away. But Carter’s captives are not Tharks, but another tribe called the Warhoons. They put Carter into the first Arena Battle™ in the ERB canon. He fakes his death in the final round with the help of his new ally, Kantos Kan of Helium, and sneaks out of the arena to freedom.

He eventually reaches Zodanga, a city of the red Martians at war with Dejah Thoris’s city of Helium. John Carter learns that the princess is a captive of the jeddak of Zodanga. The plot, already moving at a sprinter’s pace, goes to ballistic speed, and John Carter ends up leading an army of Tharks along with Tars Tarkas to rescue Helium from the Zodangan besiegers and stop Dejah Thoris’s forced wedding to the jed of Zodanga, Sab Than.

However, neither John Carter, his beloved Dejah Thors, nor Barsoom are destined for “Happily Ever After” when the planet’s decay at last reaches maximum. John Carter must go on a sacrificial final mission that may separate him forever from his love and his unborn son.

The Positives

The Positives

Much of what I’ll say about this book, both positive and negative, is of zero importance; I am a speck of dust in the cosmos that Edgar Rice Burroughs built. A Princess of Mars is one of the most influential and important novels of its century, and science fiction as the world understands it today would not exist without it. If Burroughs didn’t write it, somebody else would have to, otherwise the imagination of the human race would turn stagnant.

These are facts, not opinions. I’ll move on to opinions now.

A Princess of Mars is a monument to the power of imagination. The tidal wave of wild concepts crashing against the reader begs the question: why was Edgar Rice Burroughs wasting the first half of his life in mundane jobs? His head should have exploded from all the crazy notions caroming around inside with no outlet. Thank the Muses he found his true talent, and spent the second half of his life gushing out amazing tales. (And a few clunkers.)

The opening of John Carter’s narration is filled with the magic of great tale-spinning. Whatever other pitfalls the author experienced writing this first book, his need to express something grand and greater than the life he led before explodes in this magnificent first page. The rest of the novel delivers this promise of an astonishing story. ERB molds his experience in the American West into the canvas of an alien world, where fights between cavalry and Apaches and horse chases turn into duels with radium guns between giant green Martians and aerial pursuits in gravity-defying ships. This is the essence of escapism as art.

Starting with the framing device opening, the novel has a compulsive readability that a century has not lessened an ounce. I’ve read this book perhaps three times before, and even with this previous knowledge, I had to force myself to put the book down in order to write notes on it. It’s astonishing that a novel filled with as many plotting errors and structural problems as this can maintain constant momentum, but Burroughs’s enthusiasm pulls off the magic of hiding his neophyte bungling. The last third is a frenzy of action, warfare, and resolutions — handled with the surety of a kindergarten teacher on her first day working with a class of ADD students — but the tsunami cannot be held back.

John Carter is a Hero deserving of the capital letter H. He has a tendency toward arrogance, which will increase in the next two books, but for sheer foolhardy bravery there are few action heroes in literature who can match him for carrying along a story at a reckless pace. In the first chapter, Carter describes his core quality:

I do not believe that I am made of the stuff which constitutes heroes, because, in all the hundreds of instances that my voluntary acts have placed me face to face with death, I cannot recall a single one where any alternative step to that I took occurred to me until many hours later. My mind is evidently so constituted that I am subconsciously forced into the path of duty without recourse to tiresome mental processes. However that may be, I have never regretted that cowardice is not optional with me.

So he’s not a hero; he’s simply so straightforward brave that he looks like a hero. This is actually John Carter in a modest mood.

So he’s not a hero; he’s simply so straightforward brave that he looks like a hero. This is actually John Carter in a modest mood.

It sounds laughable, looking at ERB’s Barsoom from a distance, to think of “scientific accuracy” in a story of an inhabited Mars with fifteen-foot-tall green men, multi-armed apes, and mysterious “rays” that negate gravity; but Burroughs used much of the known science of the day (many thanks to Precival Lowell) to help create the backdrop. Earlier authors of expeditions to other planets focused on pure fantasy. Burroughs grounded his many marvels in kernels of fact: the lighter gravity, the proximity of the two moons, the desolate landscape, the lack of water. For 1912, this Mars seemed like a possible place, even if the inhabitants were exaggerated; and those inhabitants received detailed biologies and cultures that made sense within the greater scheme of Barsoom. It is nothing like the actual Mars, but it feels like a genuine planet.

The subgenre of “Dying Earth” finds early precedent here, although this is not Earth. Mars has a green and lush glory in its past, but now suffers as a dry and deprived world. The legend of a great progenitor race would find echoes throughout science fiction and fantasy that came after. Leigh Brackett’s classic The Sword of Rhiannon, also a tale of Mars, takes Burroughs’s concept of the mythic past of the planet and makes it the focus of its epic.

This Mars is also seeded with future possibilities: talk of the River of Iss that leads to the Valley of Dor, from which no inhabitant of Mars has ever returned, creates a sense of a grander setting and a deeper history. In the next novel, Burroughs sends his hero into those mysteries, but even here where they are only an illusion of depth they serve the purpose of making a believable world.

The supporting cast is wonderful. Sola’s tragic history provides a good parallel to John Carter’s adventure that doesn’t need to weigh him down with excess psychological baggage, although Burroughs ties it up too fast. Woola is a delight, one of the best animal sidekicks in fiction. Tars Tarkas is the best ally character Burroughs ever created, but his best days are ahead of him. Tal Hajus is a despicable villain, who unfortunately comes to a rapid, disappointing conclusion.

The finale with the malfunction of the atmosphere station comes roaring out of the clear Martian sky, but it’s a gutsy downer of a wrap-up. This would seem to be the end of the Mars saga, with Carter returned to Earth to live out the remainder of his life, unsure if any living thing on Mars survived. However, ERB left himself an out with Carter’s mysterious tomb that opens from the inside. The adventure is only beginning…

The Negatives

The Negatives

It’s the first Edgar Rice Burroughs novel, it started his most consistent high-quality series, it’s an established genre milestone … but A Princess of Mars has many shaky sections that show ERB’s inexperience as a novelist. As a whole, the book comes up short compared to the best work in the series that will follow in short order. A Princess of Mars contains many great parts, but Burroughs had yet to figure out how best to fit them together, and we end up with an energetic but sloppy story.

Burroughs needed a touch more practice before he perfected his action formula. (Not much, since after writing The Outlaw of Torn, his next novel, Tarzan of the Apes, shows a writer practicing his craft at near perfection.) There are large chunks of Martian data dropped for the readers’ benefit in the first half, and most of it doesn’t come from Carter uncovering it; he transports what he will eventually learns and sticks it into the present. This doesn’t hurt the pacing, even during a chapter exclusively dedicated to describing the Thark’s method of child-rearing, but it does make the story feel cluttered and takes away some of the wonder of revelation. It also prevents the narrative from getting to the actual adventure story until after Carter escapes from the city of Thark.

The story should ramp up right after Carter finds Dejah Thoris, a beautiful woman in need of rescue. But after a fast dispatch of one Thark that threatens her, Carter settles in for a calm chat with her about Martian customs, then dithers about with his new household staff. Carter and Dejah Thoris next spend a long chapter in a bonding conversation to set up their love and arbitrary conflict, but it’s all static dialogue with no other action occurring, something that Burroughs rarely let happen again. The story remains in this holding pattern (Sola’s backstory is another static pause, and it fails to develop later in the book) until the escape attempt in Thark. ERB had yet to pick up the skill to grab a potential conflict and dash like mad with it, perhaps because he still needed the confidence of a developed setting to make him feel at ease letting the story fire ahead. The meld of world-building and story plotting will become second nature to him very soon, but it’s terribly uneven in A Princess of Mars.

And Burroughs had trouble with the world-building this first time out as well. The problem isn’t with the ideas, but how Burroughs introduces them to his audience. He often uses Barsoomian terms as if the readers were already familiar with them, and then clumsily remembers to explain them later: He first uses jed and jeddak without any indication that they are titles. John Carter makes the strange assumption that Dejah Thoris and the red men of Mars also hatched from eggs, like the green men, even though he has no reason to know this. At one point, Burroughs has to cram in an explanation as to what a calot is within brackets. Burroughs had wonderful concepts this early in his career, but didn’t exactly know how to unveil them or make necessary editorial tweaks to fix the problem. This is another skill he would rapidly master, but A Princess of Mars often has a wobbly first draft feeling, perhaps because it was all a “daydream” that Burroughs scribbled onto the backs of scrap paper.

The wobbly plotting continues through to the finale, which rockets along far too fast. Carter runs from captivity among the Tharks, to captivity among the Whoorans, to a stop at the atmosphere station, then to Zodanga where he becomes a pilot, and joins the jeddak’s bodyguard, and finally races across Barsoom to rally the Tharks to join Helium in the battle against Zodanga — all in the space of a few dense chapters. The pace gets so frenzied that Burroughs skips over moments that should carry more impact, such as an important duel between two major characters that he discards in a mere sentence.

The action moves in spurts and starts: a strong build-up, a sudden ending; or vice versa. The first battle in an arena in an Edgar Rice Burroughs novel disappoints; having Carter easily fake his death and then walk out of captivity is cruelly unsatisfying. The Arena Battle™ would become one of ERB’s specialties, and feature as the centerpiece of The Chessmen of Mars. But here, he doesn’t know how to milk the possibilities.

Foreshadowing a problem that plagued Carson Napier in the Venus novels, John Carter has telepathic powers that he rarely uses, and for long stretches forgets he possesses them — probably because the author forgot as well or found them inconvenient. The telepathic powers should have been dispensed with entirely as they add little to the story except some plot-convenient short cuts.

The witty and satirical Edgar Rice Burroughs hasn’t arrived yet, aside from a wisecrack about lawyers (see below). A Princess of Mars unfolds with only a few sparks of humor and almost nothing in the way of the barbed shots at civilization that make the author’s mature work so lively even when the action isn’t pulsing.

I don’t know if this counts as something that doesn’t work for the book, but Barsoomian technology sure is bonkers. Radium guns, anti-gravity floating skiffs, atmosphere-producing station… but no advanced communication technology, and people still pull out swords and rely on draft animals.

Craziest bit of Burroughsian Writing: ERB packs in the new words: “They did not molest us, and so Dejah Thoris, Princess of Helium, and John Carter, gentleman of Virginia, followed by the faithful Woola, passed through utter silence from the audience chamber of Lorquas Ptomel, Jed among the Tharks of Barsoom.”

Best Moment of Heroic Arrogance: John Carter faces down a thousand advancing Tharks with one radium rifle.

Times a “Princess” (Female Lead) Needs Rescuing: 3

Best Creature: By Ares, take your pick! This is a smorgasbord of awesomeness. I’ll go with the white apes, which grabbed my imagination when I first read the novel twenty years ago.

Most Imaginative Idea: The whole damn thing.

The Real Author Shows His Hand: “In one respect at least the Martians are a happy people; they have no lawyers.”

Should ERB Have Continued the Series? Of course! This Mars is too amazing a place to leave it at one-and-done. The calots are loose now, there’s no stopping the revolution!

Next: The Gods of Mars

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Los Angeles, California. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

Great review!! Loved the back story of ERB. I’d heard it before but not all the details you mention and I’d forgotten the “normal bean”.

I knew that Princess of Mars was a pivotal novel for the genre, but I didn’t realize how significant it was.

I never got through Princess of Mars, but the Tarzan books is what ignited my passion for reading and the genre. So ERB does play a big part in my life.

Surely it was inadvertant that you overlooked a significant fact in your list of what isn’t good about this novel

that has had so much influence on the field of science fiction and fantasy:

It is racialist claptrap in the same way the influentially significant vile Birth of A Nation was racist claptrap that helped revise the history of what created the Civil War and why it was fought. These two works are from the same era, even.

It’s important to keep these things in mind while praising the work’s innovation, because these are facts too.

Love, C.

An interesting review.

I’ve read this book twice, and, even with certain flaws, such as those you’ve pointed out, it’s hard to put down.

The one thing that always bugged me was how Carter got from that cave to Mars.

“Racialist claptrap,” C Foxessa? That’s a strong accusation. What is there about this book that you feel is racist?

Calling someone a racist is what people these days do, Mr. Ram. It eliminates the need for thoughtful argument and the discussion of facts and ideas. Also, it is a symptom of people with existential problems stemming from guilt constructed by propaganda…usually with all the joys of life sucked out of them by their insistence on politicizing everything in Creation.

In response to C Foxessa’s comment, I say:

“Death, Death, DEATH to P.C.!!!”

I consider it nothing more than a marketing ploy by corporate elite businessmen who simply seek short term profit but have to know it’s creating MORE racism, bigotry and hatred by bottling things up rather than letting the pressure release.

Makes me especially glad the first major story in my project is an unapologetic revival of the “African Explorer” genre.

One white man to save them all, one white man to rule them ….

The solution to all problems of other people is a white man, preferably one who is either Brit or American, or even, if a creator is particularly acrobatically skilled, one who is both!

I loved the JC of Mars, and I’m certainly going to see the forthcoming movie — but one can’t overlook that JC’s history is presented as a revisionst history of the Civil War confederate as do so many of the traditional heroes of the Western, in printBirth of a Nation, and The Virginian.

This isn’t publishers’ ploys or anything like that — it is fact as people who study the history of our history and the history of literature, film and so on know.

Love, C.

Eloquently said, Tyr.

Come to think of it, I once knew someone who had an existential-minded, PCish history teacher at high-school. This teacher contended that Edgar Rice Burrough’s Tarzan books were racist. Why? Because Tarzan did not, according to the teacher, have any romantic relations with any local black tribes-women before he met Jane, a white woman. So racist was ERB, he said, that he thought of having Tarzan smitten by one of the female apes before the thought entered his mind that he could be smitten by a black woman.

Now for the amusing part (at least to some people). When asked if he had ever actually read any of the Tarzan books, the teacher, suddenly looking a little foolish, admitted he had not.

Apparently he had his mind set to “automatic PC.” So, perhaps it’s easy to find political incorrectness if you expect to find it in advance.

Actually, Foxessa, the problems of mankind can be solved, not by looking to a white Anglo, but by looking to an olive skinned Jew born in Palestine a couple thousand years ago. However, I suspect that is your least favorite man of all.

Gentlemen, if you think C Foxessa is wrong about the book, you can point out to her where the text disproves her assertions. If your position is right, then there will be plenty in the text to back you up. (Since it’s a book I have not yet read, I have no idea who is right in this disagreement.) Making assumptions about her religious views, entirely in the absence of evidence, seems a strange way discredit her objections to Princess of Mars.

I originally thought to stay out of the comments section here, but at this point I think I need to make some remarks about the race issues in A Princess of Mars, as well as explain why I didn’t originally include them in my review.

When writing about pulp, in which racist assumptions are almost always prevalent, I’ve made the decision to address racism in the work if it is one of the primary reasons for the existence of the work, or if the author gets up on a soapbox to preach racist ideology. “Pigeons from Hell” is a good example of the former; that story is entirely linked to race issues, and it is impossible to discuss the story without it. In fact, the race issues of Howard’s horror tale is one of it’s most intriguing aspects. Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Lost on Venus is an example of the latter; ERB halts the story to give an obnoxious lecture on eugenics that is thoroughly loathsome and reflect the author’s own views on the topic. It also completely kills the pacing.

In the case of A Princess of Mars, aspects of racism appear toward Apaches who appear in the first chapter. Burroughs participated in Apache-hunting during his brief military career—although the only Apaches he ever met were the scouts who worked with the 7th Cavalry, whom he later wrote that he quite liked—so he brought some of the attitudes of the cavalrymen to John Carter in this section. (Carter refers to the Apache as “vicious marauders.”) This transfers onto Mars, which is in many ways a pseudo-Western setting, with certain Martian groups serving the part of the “savage tribes,” such as the green men, although it is definitely not a one-to-one analogy, and Burroughs uses the Western inspiration in a free-floating way. The Barsoomian cultural landscape is an intricate place.

A Princess of Mars uses a standard trope, most recently discussed regarding the movie Avatar, of the white man who joins another culture and then becomes its most powerful member. What makes A Princess of Mars different from many stories that follow this archetype is that John Carter doesn’t side exclusively either with the green Martians or the red Martians. He sides with the Tharks among the green Martians, but opposes the Warhoons. He sides with the red Martians of Helium against the red Martians of Zodanga. His principle drive is Dejah Thoris.

(It’s intriguing that the “red men” of Barsoom tend to be the heroes, and the “white Southern gentleman” hero falls in love with a “red woman.” This was probably not an intentional statement on Burroughs’s part—in fact, I’m certain it isn’t given what else I know about the author’s opinions—but it reads subversive today. I’ve tried to find contemporary opinions on A Princess of Mars to see if anybody had a fit about a white hero in a love with a person of a different skin color, but perhaps because Dejah Thoris is an alien people didn’t think about it. Which is probably why ERB wasn’t thinking about it much either.)

As for the Civil War: The film The Birth of a Nation is a racist screed, through and through. It’s director D. W. Griffith on a soapbox preaching the Southern Myth of Reconstruction that turned into the main narrative in the late 1870s that tried to rewrite why the Civil War was fought. Griffith used the medium of film to make the myth more widespread, and there is no doubt that the pushing of this racist ideology was the main point on its agenda.

A Princess of Mars is not preaching about the race assumptions in it; they are there as a part of the the assumptions of the author and the period. The book is one of the less “message-themed” of the Burroughs canon. (Next year’s The Gods of Mars gets into a satire about religion, so we do not need to travel far before ERB started overtly projecting.)

Specifically regarding the Civil War in A Princess of Mars: the novel deals with the conflict briefly, and has little to say about it aside from getting the story going in the first chapter. Based on Burroughs’s family background (which I’ll go into in more detail below), I do not believe that ERB bought into the Southern Myth of Reconstruction, except in the general way that it was permeating culture. The novel isn’t interested in preaching about the Southern view of the Civil War, and John Carter hardly mentions the war once he gets to Mars. A Princess of Mars contains racist views; but it is not a racist polemic, which The Birth of a Nation most certainly is.

For the record, here are the racially-tinged quotes in the prologue (narrated by “ERB”) and Chapter I that refer to the Civil War. (Emphasis mine.)

The prologue has little more to say about the Civil War. It skips ahead to Carter as a miner and his mysterious decade-long disappearance.

The real Edgar Rice Burroughs, as opposed to the fictional version in the prologue, not only wasn’t born before the Civil War, but was not a southerner at all, nor was his family. They were firmly on the Union side. Burroughs was born in Chicago to a Civil War veteran from Massachusetts who served in the Union Army. In fact, Major George Tyler Burroughs left his lucrative job in a large New York import firm to enlist because he believed in the cause, despite his employers begging him to stay.

What to make of Burroughs, no Confederate sympathizer, creating a fictional version of himself from the South who lived on a slave-owning plantation? It may just be that ERB thought a Virginian on the losing side of the war might make an interesting hero, or he bought into the image of the “southern gentleman” as a knightly figure. I don’t know; Burroughs is often a difficult man to know, and I’ve read almost all his work as well as extensive biographical material and still find him frequently baffling. Often, the mysterious nature adds to the enjoyment of his work—even when I disagree with what he is saying, as in Lost on Venus.

(Side note: ERB’s mother wrote an interesting memoir about being a Northern “War Bride.” It can be read here.)

John Carter’s statement on his Civil War service:

Carter has nothing more to say about his service. He never mentions it when he returns to Earth. When telling his history to Dejah Thoris in Chapter XI, he mentions that he is a “gentleman of Virginia,” but says nothing about the Civil War. (In fact, he tells Dejah Thoris only a barest outlines of his past history before she leaps in and tells all that she knows about Earth already.) Aside from this “southern gentleman swagger”—which will become crazy arrogance in the later books—John Carter has zero interest in his past once he reaches Barsoom. This may be because, as Burroughs’s family history indicates, he didn’t care about the Confederacy at all except as a backdrop for his character.

In fact, it would be bizarre if John Carter said anything pro-North; I wouldn’t believe a wealthy white Southerner in 1866 having a Northern view about the war’s outcome. In fact, Carter is surprisingly reticent to be pro-Southern. I think this is Burroughs’s Yankee background coming through.

But I think C Foxessa has a point when she singles out this thematic idea: “The solution to all problems of other people is a white man, preferably one who is either Brit or American, or even, if a creator is particularly acrobatically skilled, one who is both!” This is a very common assumption from not only literature of the period, but books and movies today. I do not think A Princess of Mars is preaching about the Civil War in the way of Birth of a Nation. But the Southern Myth of Reconstruction was something many writers, even a Yankee one like ERB, took for granted in 1912, and this comes across in aspects of Carter’s character.

And, looking at what I just wrote . . . man, this would have been one long damn review. Okay, maybe the comments section is a good idea. Consider this an “Appendix” to the above review.

I just finished reading (for me, re-reading) Princess to my boys as prelude to the movie. I’ve read a majority of the Martian books — though don’t ask me which ones, since they all blur together.

You’d have to be cross-eyed wearing sunglasses and horse blinders to interpret Princess as having anything to do with the Civil War, Reconstruction, or historical revisionism. Ryan highlights the pertinent paragraph: ERB wanted his hero to be a great soldier; in 1912, the Spanish-American War was the most recent US conflict — and thus perhaps too sensitive; but the Civil War was recent enough without being too incendiary. Yet if Carter brings the warrior sauce of awesome, why is he unemployed or at least not a successful businessman like ERB’s father? Why is he a down-and-out prospector in Arizona? Because he was a Confederate. Problem solved. At book’s end, Carter is living along the Hudson River, so ERB clearly isn’t that enamored with the south.

And it makes for the bonus joke, “At the close of the Civil War I found myself possessed of several hundred thousand dollars (Confederate),” which is the best gag in an otherwise humorless book.

What’s more interesting is ERB’s conflicted attitude toward Native Americans, if we assume the Tharks and Warhoons are stand-ins for the Apache and Amerindians in general. In one breath he loves the Noble Savage and their freedom from the metaphorical and literal restrictions of Western Civ (no clothes!), then reviles them in the next. What to make of his criticisms of Thark culture, with its abolition of the nuclear family, lovelessness, communal child-rearing, infanticide of the weak, common property (the livestock), snitches (Sarkoja), slavery, and constant war? The easiest interpretation is that this is, to ERB’s mind, a direct analogy to Native American culture; but in 1912, could it also be a criticism of Marxism? Thark culture, though nomadic, has a lot in common with ancient Sparta, which was very much a totalitarian society. But wait! In 1912, Marxist totalitarian states had yet to rise. So was ERB predicting that Marxism would lead to totalitarianism not unlike that of classical Sparta?

Layers, people! This book has layers!

Hello, Sarah. Surely it is for C Foxessa to prove her position and to give examples of how Princess of Mars is racist, since she is the one who brought this up.

Are you satisfied with her reasoning? So far, I’ve seen nothing to support what she claims. There was no supporting evidence in her first post, just a bold general assertion of racism. A “fact” she called it without any elaboration. In the second post she speaks about John Carter being a Confederate, with the automatic implication that he is therefore a racist — another “fact” — and speaks of “One white man to save them all, one white man to rule them,” etc., but, unless I’m very much mistaken, this line is nowhere to be found in the text of the book. Rather, she is telling us what she thinks ERB is thinking.

To be fair to C Foxessa, when looking at Princess of Mars through a Post-Colonial lens it is clearly a prime example of colonial race favoritism writing. As Ryan points out, there are specific examples of Burroughs’ own racism regarding Apaches early in the book.

What Foxessa doesn’t address is that being a colonial era book, with colonial archetype expressions, the book should be viewed as such and not dismissed swiftly as “clap trap.” I would even argue, had I the time, that the book is subversive in many ways regarding race — at least in the minds and imaginations of the readers if not in author’s intent.

One must also consider that Post-Colonial, Post-Structural, and Critical lenses are just that, they are lenses through which to view a piece of literature. They are not the only way that a text can, or should, be read.

I find the linking of Birth of a Nation to Princess of Mars extremely problematic for the very reasons that Ryan states, so I won’t expand on the idea much except to say that the depictions of African-Americans in Birth are vile and visual representations meant to shape the viewer’s opinions. In Princess, Carter’s racism toward Apaches is a stated opinion — and one that fits within accepted bounds of a character participating in the “War of the West.” I would not expect a person who fought in those wars to have a modern view of the exploitation and subjugation of Native American nations.

Jackson,

Burroughs’ book “The Moon Maid” is expressly an anti-Marxist work. It bears many similarities to Princess and so you might be on to something there.

Ryan, though I haven’t read Lost on Venus and a lot of his other non-Tarzan books, I don’t doubt that ERB showed dubious taste at the very least and demonstrated racist leanings. But as for Princess of Mars, which is the book this article is about, I have yet to see any compelling evidence that it is a work with racist overtones.

I don’t see how Carter referring to the Apaches as “vicious marauders” can be classified as racist. Isn’t it likely that the Indians at the same time also referred to the whites as “vicious marauders” or worse? Isn’t it likely that throughout history, warring tribes and armies have referred to the other side in terms such as these? Isn’t it also fair to say that they often did so without any thought to what race the other side was? When someone is in a battle, it’s kill or be killed, and at that moment there is no consciousness of what the person’s skin colour is, it seems to me. He is just someone to be killed and ground into the dust. Someone whose equally red blood you just want to see spilled. And afterwards if your defeated enemy has money, a gold ring, a jeweled dagger or some other valuable item, then he is just a dead body to be robbed.

You wrote that you found evidence of racism in this:

We all loved him [John Carter], and our slaves fairly worshipped the ground he trod.

It seems to me that you are saying that, since Carter was a slave owner, then he must be a racist. I wonder, though, isn’t it possible to be a slave owner and at the same time not a racist? For all we know, John Carter could be what might be termed a “reluctant slave owner,” one who inherited his slave plantation from his slavery-loving father. No doubt most Civil War era slave owners were racists and hated their slaves, but let us be open to the possibility that some felt otherwise.

The Romans, Greeks, Vikings, Arabs, Byzantines — well, just about everyone back in the day, it seems — all had slaves. That is, the elite or well-off had them. Most of those slaves would have been white, by the way.

Now, if we apply modern standards and conceptions, many people — at least in modern post-slavery America — might be inclined to automatically assume that if a Roman had a black slave, he must have been a racist, even while his neighbour, who has a white slave, is not considered a racist.

Anyway, the last thing I’ll probably say on this rather sensitive subject is this. While it is perfectly possible that ERB held “racialist claptrap” notions, it is also possible that there is no direct influence of racism interjected into Princess of Mars. As for his other novels, that’s a separate issue.

Jackson and Christian,

Another of his anti-Communist books is Pirates of Venus (which I reviewed) that makes the “Thorists” an overt symbol for the Soviets. Unfortunately, Burroughs failed to do much interesting with it. Moon Maid is far better in that regard, and ERB originally intended it to be even more overt with the Soviets as the villains, but this planned novel Under the Red Flag changed over the years, with more SF concepts to make it allegorical, and the Kalkars becoming the stand-ins for the Soviets.

Henry, I don’t think it has racist overtones. I think it has racist undertones that come from the time and ERB’s background. Compared to some of ERB’s later novels, A Princess of Mars is subdued in the extreme in regards of race.

Also, Carter isn’t the slave owner in that quote. We don’t know if Carter owned slaves; he never says anything about it. The slave owner in that quote is the fictional ERB. Which, as I’ve mentioned before, is really weird considering that the real ERB was from Chicago and a family that fought for the union. Also, that quote is the only mention of slaves in the American South in the whole novel.

And by the way, that ERB still provokes these kind of discussions a century later is one of the reasons I find the man and his work endlessly fascinating. As Jackson said, “Layers.” ERB’s work is filled with differing interpretations and ideologies that belie the simple adventure plots that would seem to drive them, whether issues of race or politics or science. I seriously never get tired of looking into the man’s work—even with some of his poor novels.

One day I must write about his two novels about the Apaches. Amazing material there.

Ryan, thank you for that long comment. Putting Princess of Mars in the larger context of ERB’s other works was especially helpful.

I read a bit of ERB’s mother’s memoir, wondering whether she meant “war bride” in the currently understood sense, of a bride from the defeated side who marries a soldier from the victorious side. That would have made sense of ERB’s decision to make Carter a southerner–it might have been a thought experiment about who he could have been among his mother’s people. But no, as far as a bit of googling and a read of the first chunk of the memoir turned up, it looks like she was a Chicago girl, and by “war bride” meant merely that she had married a soldier in wartime. (Oh, well. I liked my imagined version of his mom’s bio better. More layers of conflict.)

Henry, I would agree with you, except that the arguments against her took such a turn toward ad hominem attacks. I’m not sure how seeing racism where it might not be is evidence that a person hates all men in general and Jesus in particular, and when people start demanding “Death, Death, DEATH!” to an idea they ascribe to a fellow commenter, well, that’s problematic and deserves to be noted.

Ryan’s approach, explaining thoughtfully why he disagreed with her analogy between Princess of Mars and The Birth of a Nation was far more persuasive. I also found useful his distinction between racist overtones, by which I think he means a deliberate agenda that’s not entirely overt, and racist undertones, by which he clearly means ideas that are common in the author’s community and that get into the work by a sort of unintentional cultural osmosis. That’s what an online conversation among people with differing opinions can be. No virtual shouting needed.

Ryan accuses ERB of overt racism against the Apache’s because “Carter refers to the Apache as ‘vicious marauders.’” I think it’s worth pointing out that John Carter and ERB are not the only people who have ever characterized the Apache as ‘vicious marauders.’ Among those who did so were the Hopi and Zuni tribes, who were the victims of, well, vicious marauding, by the Apache for generations before any “red” man ever saw a “white” man. In fact, one possible source of the very word “apache” is from a Zumi word meaning “enemy.”

Several Native American people were warlike marauders, somewhat equivalent to, say, Vikings or Huns. The Haida of the PNW were not well-liked by the more peaceful Salish tribes. Point is, there was no one “Native American” culture. There were instead hundreds of tribes with different cultures, ranging from peaceful to predatory. Just like Europe, Asia, and Africa.

ERB specifically casts Apaches as the attackers, not Hopi or Zuni or some other tribe. Perhaps he was a racist who disliked “the red man.” Or perhaps he was someone with personal contact with multiple tribes as they were at the close of the West and understood the differences between Apache and Hopi.

[…] Installment: A Princess of Mars (1912), The Gods of Mars […]

[…] Installments: A Princess of Mars (1912), The Gods of Mars (1913), The Warlord of Mars […]

[…] Installments: A Princess of Mars (1912), The Gods of Mars (1913), The Warlord of Mars (1913-14), Thuvia, Maid of Mars […]

[…] making John Carter of Mars the true title of his adaptation of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s classic A Princess of Mars. Stanton, a fan of the Martian novels since he was a child, has given the perfect fan treatment to […]

[…] almost to a fault, is honestly amazing. The screenplay fashions a plot that diverges from A Princess of Mars, but in all other respects the movie is the vision of Edgar Rice Burroughs brought to cinematic […]

[…] Installments: A Princess of Mars (1912), The Gods of Mars (1913), The Warlord of Mars (1913-14), Thuvia, Maid of Mars (1916), The […]

[…] Installments: A Princess of Mars (1912), The Gods of Mars (1913), The Warlord of Mars (1913–14), Thuvia, Maid of Mars (1916), The […]

[…] Installments: A Princess of Mars (1912), The Gods of Mars (1913), The Warlord of Mars (1913–14), Thuvia, Maid of Mars (1916), The […]

[…] Installments: A Princess of Mars (1912), The Gods of Mars (1913), The Warlord of Mars (191314), Thuvia, Maid of Mars (1916), The […]

[…] end up as a movie a year after publication, and yet fans had to wait a century to get a movie of A Princess of Mars? I’ve failed to locate any copies or online versions of The Oakdale Affair, even short clips; it […]

[…] in August), more viewers have come to appreciate this live-action take on a groundbreaking novel A Princess of Mars. Perhaps the cult status will kick in, although so far I haven’t seen […]

[…] Although pulp magazines existed before Burroughs published Under the Moons of Mars (later titled A Princess of Mars) and Tarzan of the Apes, this double-punch in 1912 changed the style of this publishing medium for […]

[…] these ideas come from? How did this man, who showed no inclination toward creativity before penning A Princess of Mars, become, in the words of Ray Bradbury displayed on the company website, “The most important […]

[…] Outlaw of Torn. Considering that chronologically it is squashed between his two most famous books, A Princess of Mars and Tarzan of the Apes, it makes sense that The Outlaw or Torn gets overlooked. That it belongs to […]

[…] Bradbury, George Lucas, James Cameron, and George Lucas. But he also, as Ryan Harvey says over at The Black Gate, “re-shaped popular fiction, helped change the United States into a nation of readers, and […]

[…] a 4X strategy game along the lines of Sid Meier’s Civilization. As Ryan Harvey said over at The Black Gate, Burroughs “re-shaped popular fiction, helped change the United States into a nation of […]

[…] A Princess of Mars by […]