The Centenary of Mervyn Peake

July 9, 2011 will be the hundredth anniversary of the birth of Mervyn Peake, the author of three remarkable fantasy novels: Titus Groan, Gormenghast, and Titus Alone. The books — published in 1946, 1950, and 1959 — form a series (along with the novella “Boy in Darkness,” which I have not read) following the early life of Titus Groan, Seventy-Seventh Earl of the immense castle called Gormenghast. Peake had intended to write a longer sequence of novels about Titus; he planned two more books, but the advent of Parkinson`s Disease made that impossible. A number of activities are being planned to commemorate Peake’s centenary, including the publication of a fourth Titus volume, Titus Awakes, written by Peake’s wife after his death in 1968.

July 9, 2011 will be the hundredth anniversary of the birth of Mervyn Peake, the author of three remarkable fantasy novels: Titus Groan, Gormenghast, and Titus Alone. The books — published in 1946, 1950, and 1959 — form a series (along with the novella “Boy in Darkness,” which I have not read) following the early life of Titus Groan, Seventy-Seventh Earl of the immense castle called Gormenghast. Peake had intended to write a longer sequence of novels about Titus; he planned two more books, but the advent of Parkinson`s Disease made that impossible. A number of activities are being planned to commemorate Peake’s centenary, including the publication of a fourth Titus volume, Titus Awakes, written by Peake’s wife after his death in 1968.

The Titus novels are excellent books. Each seems to have a slightly different style, a different approach to Titus and his world. All of them are stylistically and imaginatively rich; although the explicitly fantastic is rare in the books, arguably nonexistent, there is in each of them an approach to world-building, a readiness to leave behind the rational, that I think makes them fantasy more than anything else — so long as you use “fantasy” in its broadest sense, agreeing that contemporary genre expectations have nothing to do with the variety implicit in the word.

Put it this way: Peake wrote before fantasy fiction had been defined as a form, but from where we stand now, his work is more easily assimilable to fantasy than to anything else. He’s been a strong influence on fantasists like Michael Moorcock; Lin Carter published his books as part of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. But like a lot of early fantasists, Peake is somewhat apart from the conventions of fantasy we now know. His books have little to do with medievalism or any historical culture, but neither do they seem to reflect the modern world (except in the last of them, and that’s a world as strange and distorted as a Terry Gilliam movie, a setting that, it has been said, prefigures the fantasy of steampunk). As an illustrator, Peake was working on Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and the Grimms’ Household Tales while writing Titus Groan; those may be useful places to start.

The first two books take place in and around the immense castle called Gormenghast, while the last takes place in a hyper-modern unnamed city. These settings are wonderlands, of a sort, with logics of their own. Not only do they operate according to their own rules, but those rules are constructed according to highly distinct value-systems. The society of Gormenghast is based on customs and tradition, smothering individual thought; the city is fascinated by science and technological thinking, to the point of absurdity. And: the city can produce fairy-tale-like wonders that become horrors because of the inherent cruelty and stupidity of human beings. Gormenghast is a fairy-tale castle that allows none of the freedom of fairy tales. It is a construct of history, and of rules. It has aspects of the wondrous, but insists on ways of life that deny that wonder, that shackle it beneath ritual and occulted history.

The first two books take place in and around the immense castle called Gormenghast, while the last takes place in a hyper-modern unnamed city. These settings are wonderlands, of a sort, with logics of their own. Not only do they operate according to their own rules, but those rules are constructed according to highly distinct value-systems. The society of Gormenghast is based on customs and tradition, smothering individual thought; the city is fascinated by science and technological thinking, to the point of absurdity. And: the city can produce fairy-tale-like wonders that become horrors because of the inherent cruelty and stupidity of human beings. Gormenghast is a fairy-tale castle that allows none of the freedom of fairy tales. It is a construct of history, and of rules. It has aspects of the wondrous, but insists on ways of life that deny that wonder, that shackle it beneath ritual and occulted history.

Stylistically, the first book is appropriately still. It moves slowly, on the one hand seeming to want to describe every aspect of the castle from the kitchens to the topmost attics, while on the other hand insisting on the impossibility of completely capturing the immensity that is Gormenghast. It’s almost Dickensian in its use of language, and in its mixture of highly-detailed realistic character drawing with the grotesque; it specifically recalls the Dickens of Bleak House, the complex incomprehensible rituals of Gormenghast substituting for the complex incomprehensible systems of London.

Readers who find Tolkien slow will have a difficult time with this book. The language is rich and beautiful, the sort of prose that lulls one into long reveries. But the pace of the story is correspondingly leisurely. Consider the following paragraph, in which a man bites a pear:

Making use of the miniature and fluted precipice of hard, white discoloured flesh, where Fuchsia’s teeth had left their parallel grooves, he bit greedily, his top teeth severing the wrinkled skin of the pear, and the teeth of his lower jaw entering the pale cliff about halfway up its face; they met in the secret and dark centre of the fruit — in that abactinal region where, since the petals of the pear flower had been scattered in some far June breeze, a stealthy and profound maturing had progressed by day and night.

So the entire paragraph is about one bite of a pear. But it works, both as a piece of prose and as a play with the symbols and themes of the book. The whole of the paragraph is a single sentence, carefully constructed and paced, gaining weight and moment as it proceeds. The vocabulary is not only lush (‘abactinal’ wasn’t in the first dictionary I consulted; it means roughly ‘away from the mouth ’), but is applied in distinctive ways — the description of the flesh of a pear as “fluted,” for example.

But the image is also directly relevant to what’s happening in the story; what’s happening with the man doing the biting, the scheming kitchen-boy named Steerpike, and with the girl who gave him the pear, Titus’ older sister, Fuchsia. Steerpike, who has just climbed the cliffs of Gormenghast’s stone walls, has entered Fuchsia’s secret chamber, her retreat, where she is maturing in a way unknown and unseen by the castle residents around her. Steerpike dreams of taking power in Gormenghast, and soon realises he can do so through Fuchsia, hatching long and devious plans to play on the secret parts of her soul that she doesn’t even realise exist, in order to seduce her and marry her. The pear becomes an emblem of both of the characters, and of what might happen between them.

But the image is also directly relevant to what’s happening in the story; what’s happening with the man doing the biting, the scheming kitchen-boy named Steerpike, and with the girl who gave him the pear, Titus’ older sister, Fuchsia. Steerpike, who has just climbed the cliffs of Gormenghast’s stone walls, has entered Fuchsia’s secret chamber, her retreat, where she is maturing in a way unknown and unseen by the castle residents around her. Steerpike dreams of taking power in Gormenghast, and soon realises he can do so through Fuchsia, hatching long and devious plans to play on the secret parts of her soul that she doesn’t even realise exist, in order to seduce her and marry her. The pear becomes an emblem of both of the characters, and of what might happen between them.

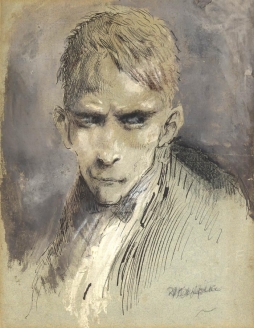

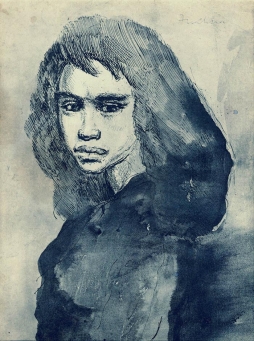

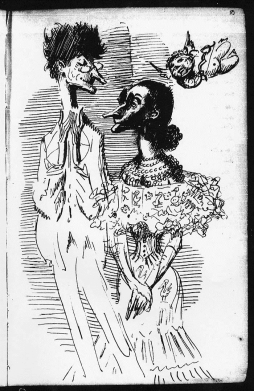

Peake’s art is, in a sense, an art of emblems. It is an almost visual art, as Peake was also an accomplished visual artist (you can see his illustrations of some of his characters later in this post, taken from mervynpeake.org). In the first book, the emblems are realistic things, that are supported by extensive character backgrounds; you know who the people are as you watch them slowly move through their tableaux. By the third book, emblems, images, are given one after the other with much less detail, as Titus tries to understand the world around him. It’s a terser, more explicitly satiric style.

The first book begins with Titus’ birth, and covers roughly the first two years of his life. There’s a sense that he brings change to the castle, but unsurprisingly, the infant Titus can hardly be said to dominate the book — that’s more the province of Steerpike, the social climber (and, indeed, literal climber upon the walls of Gormenghast). The second book skips forward a few years, and follows Titus’ adolescence. In theory, at least; in fact, for much of the book, Titus seems more of a sub-plot, appearing now and again in the lives of the adults who seem to carry the majority of the novel. More charitably, one could view Titus as a structural device, unifying a diverse narrative of murder, politics, and love among gerontocratic academics. Over the course of the book, he slowly emerges as a character, as a significant actor in events, leading up to his ultimate choices in the book’s final pages.

If the second book is more bluntly symbolic and satiric than the first — and there’s no other way I can think of to look at the extended romance of Titus’ teacher Bellgrove with Irma Prunesquallor, the sister of the castle’s doctor — then it moves correspondingly faster. Steerpike’s plans put him in authority over Titus, and even establish him as the master of the castle’s many rituals. Conflict between the two is inevitable. At the same time, Titus is drawn to the mysterious daughter of his former wet nurse, a creature who is outcast from all human community and language, and who is therefore a symbol of freedom and life beyond the castle.

If the second book is more bluntly symbolic and satiric than the first — and there’s no other way I can think of to look at the extended romance of Titus’ teacher Bellgrove with Irma Prunesquallor, the sister of the castle’s doctor — then it moves correspondingly faster. Steerpike’s plans put him in authority over Titus, and even establish him as the master of the castle’s many rituals. Conflict between the two is inevitable. At the same time, Titus is drawn to the mysterious daughter of his former wet nurse, a creature who is outcast from all human community and language, and who is therefore a symbol of freedom and life beyond the castle.

Peake’s themes, here as elsewhere, are obvious: the conflict of tradition and the individual. But Steerpike muddies the water intriguingly. He claims to be motivated by the ideal of equality, but we see clearly that he’s mainly driven by powerful self-interest. He’s essentially psychopathic, emulating emotions to play about with other people, himself utterly unfeeling. Although he plays at being a revolutionary when it’s convenient, shocking Fuchsia with his irreverance (for she cannot see the careful planning behind the postures he adopts), he schemes and murders to become the man who oversees the daily rites of the castle — who upholds traditions, and proclaims how the traditions are to be carried out.

I suppose you could see Steerpike as a symbol of the bourgeois class, acting out of self-interest, mouthing anti-aristocratic and revolutionary slogans only to revel in law and tradition once they have assumed power for themselves. But I think he’s more usefully seen as Titus’ shadow, his opposite number. Titus is born to inherit a role in Gormenghast that Steerpike strives for; Titus doesn’t want it, but must resist Steerpike’s schemes and ordinances or be crushed. Steerpike wants power more than anything; Titus wants only to be free of power. It’s no surprise that the climax of the book is a death-struggle between the two. One could say: in order for Titus to emerge as a character, Steerpike has to be deposed or slain.

I don’t know if Peake was interested in Jungian psychology, but there is an archetypal sense to many of his characters. If Steerpike is Titus’s shadow, his repressed opposite, then the Thing, the daughter of Titus’ nurse, is his anima. The anima’s an image of the female that a male has inside his psyche (a female has a male image, an animus); development or union with the anima, according to Jung, fuels creativity. In the book, Titus is fascinated by the Thing, drawn to her after only a glimpse. The obsession that quickly develops, the sense of importance she comes to have to him without his ever speaking to her, are symptoms of a more-than-conscious significance. For Titus, she comes to symbolise freedom from Gormenghast. When, after a fleeting encounter, she dies, it is a significant marker in his life:

I don’t know if Peake was interested in Jungian psychology, but there is an archetypal sense to many of his characters. If Steerpike is Titus’s shadow, his repressed opposite, then the Thing, the daughter of Titus’ nurse, is his anima. The anima’s an image of the female that a male has inside his psyche (a female has a male image, an animus); development or union with the anima, according to Jung, fuels creativity. In the book, Titus is fascinated by the Thing, drawn to her after only a glimpse. The obsession that quickly develops, the sense of importance she comes to have to him without his ever speaking to her, are symptoms of a more-than-conscious significance. For Titus, she comes to symbolise freedom from Gormenghast. When, after a fleeting encounter, she dies, it is a significant marker in his life:

It was his youth that had died away. His boyhood was something for remembrance only. He had become a man.

Like Steerpike, the Thing is annihilated once Titus has assimilated what she has to teach him, once he has grasped her lesson of freedom.

(It is perhaps notable that the books are likely less subversive now, in many ways, than they might have seemed when they were first published. While Titus rejects the established order, he does so as the child of privilege. The class rebellion of Steerpike is seen as sinister, and his protestations of equality a mask for self-interest if not outright sadism. Women in the books are typically figures of mockery, tragically inadequate, or both; and two females die essentially so that Titus can gain greater understanding of himself. But then one can also say that all other characters in all the books are ultimately there in order to illuminate Titus and his journey. In the end, this is the story Peake chose to tell, for whatever reason, and Titus is the character he wanted to write about.)

The third book, Titus Alone, is very different from the first two. It has an odd publication history, which involves an overly-enthusiastic editor who cut out much necessary material from the first printing of the book. Editorial work has since been put in undoing the first editorial job, and the resultant text is probably reasonably close to what Peake had in mind.

The third book, Titus Alone, is very different from the first two. It has an odd publication history, which involves an overly-enthusiastic editor who cut out much necessary material from the first printing of the book. Editorial work has since been put in undoing the first editorial job, and the resultant text is probably reasonably close to what Peake had in mind.

In any version, the book is much shorter than the preceding two, and moves much faster. It seems to be a series of symbols, a strange looking-glass world structured around a fantastical city. It’s not depicted with the richness of Gormenghast; it can’t be, given the approach Peake took, and the relative terseness of the writing. Instead it’s a series of nightmare flashes, through which Titus moves, encountering various grotesques and protesting against being reduced to a symbol even as the narrative insists on it. I find it oddly effective, a direct connection to a storehouse of surreal imagery. But, perhaps because it is so short and concise and surreal, for many readers it lacks the power of the preceding books. Personally, I’d say that after the weight of Gormenghast, Titus’ adventures here seem oddly transitory, his development as a character rudimentary.

Still, there is a glorious use of language in Titus Alone, and it is through that greatness of language that the books succeed. The lack of overt fantasy is somewhat occluded by the lushness of the prose, which heightens the moments that come close to magic, to true fantasy. Whether we are in the real world or not becomes hard to tell; the stylistic excellence makes magic out of language.

Gormenghast’s breadth becomes unnatural, a structure which is never a playground or shelter for Titus but only a monolithic citadel of oppression. The death of Titus’ father, in a strange mixture of nighttime rain and moonlight, comes at the hand of giant owls. The swiftness of the Thing, of Titus’ symbol of freedom, is perhaps more than can be explained by natural means. The language describes these things, but elevates them, giving them emotional resonance and significance, a heightened intensity literalised as a challenge to everyday reality, that pushes them toward the fantastic.

These books are about escape. About the escape from past customs, but also about the necessary suspicion of the technological world — of the human tendency to create new rituals, to find new meaningless shibboleths to rule our lives. In fact one could also say that the books are about ritual; about the way some people, like Titus’ parents in their different ways, use ritual as a crutch. The story insists that ritual does not inspire transcendence or understanding; that freedom comes only from the abandonment of rites. The novels are profoundly satiric, but deeply serious.

These books are about escape. About the escape from past customs, but also about the necessary suspicion of the technological world — of the human tendency to create new rituals, to find new meaningless shibboleths to rule our lives. In fact one could also say that the books are about ritual; about the way some people, like Titus’ parents in their different ways, use ritual as a crutch. The story insists that ritual does not inspire transcendence or understanding; that freedom comes only from the abandonment of rites. The novels are profoundly satiric, but deeply serious.

Because Peake ultimately published three books about Titus, because he was writing at about the time Tolkien published The Lord of the Rings, and because the general critical vocabulary about fantasy seems to have been particularly poor at about that time, Peake and Tolkien have often been contrasted. I don’t see it as a particularly valuable exercise. The writers have completely different interests and ambitions, and the books are very different in technique and tone. Personally, I think that we have not yet caught up to the artistically and socially radical techniques of Tolkien (as I wrote about here), while in many ways we’ve come closer to Peake; but the two writers don’t seem to me to particularly speak to each other.

At any rate, Peake’s books overall are a great accomplishment, worth reading not only for their use of language and unconventional deployment of symbols, not only for their intense visual sense, but also for their uncompromising insistence on telling the story in its own good time — for their ability to find power in the slow build of the books’ pace. I wish that the whole, as Peake planned it, could have been accomplished; I wish I could have learned what Peake intended for Titus’ final fate. What we have is sadly incomplete. I imagine a fantasy counterpart to something like A Dance to the Music of Time; a series of separate books examining (in this case) the different stages in the life of a single remarkable figure. If there is a weakness in the books as they exist, in fact, it is that Titus is not particularly remarkable, even dull next to the panoply of characters around him. Would that have changed as he aged? No-one can say.

But if the books make an incomplete sequence, they’re still worth reading. They’re a landmark of fantasy fiction, and suggest new ways to think about magic and writing. Peake’s work is individual, distinctive, and resonant; it’s the perfect realisation of a certain way of thinking about prose.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His new ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

I still have my Ballantine editions from the 70s, and loved these books when I read them then, and am now delightfully re-reading them in time for the new book’s arrival. Yes, the language of these books is a visual feast indeed.

Have you seen this —

“A celebration of the writing and art of Mervyn Peake — Mervyn Peake, creator of Gormenghast, is now recognised as a brilliant novelist and artist. Michael Moorcock, China Miéville, Hilary Spurling and AL Kennedy celebrate his achievements — ”

In the UK Guardian here.

Love, C.

Thanks for the link!

[…] In an article for Black Gate magazine, Matthew David Surridge analyses Peake’s novels. […]