A review of The Door Into Fire by Diane Duane

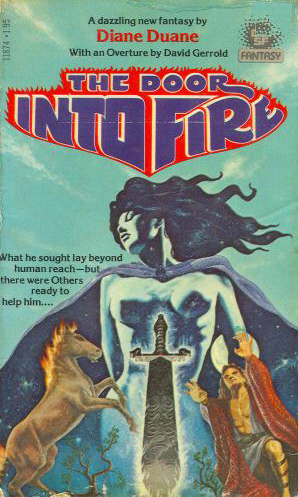

The Door Into Fire, by Diane Duane

The Door Into Fire, by Diane Duane

Dell Fantasy (304 pages, $1.95, 1979)

Prince Herewiss of the Brightwood has two major problems.

First, he’s the first man in generations to have the Flame, a form of energy that’s much more potent than ordinary sorcery — but he can’t use it at all if he can’t make a physical focus with which to channel it.

His other problem is his lover Freelorn, exiled Prince of Arlen and trouble magnet. The summary on the back of The Door Into Fire refers to Freelorn as Herewiss’s “dearest friend” — which, in my opinion, does the book a disservice.

The Door Into Fire is about magic power, overcoming old tragedies, and the beginning of an epic kingdom-changing quest. It’s about a very hands-on Goddess and how she deals with her creation.

But it’s also about sex. Sex and love, sex and jealousy, sex in a culture where bisexuality and polyamory seem to be the default — sex that starts from a different set of assumptions than the average American reader carries around.

Without the relationships between the characters, human and inhuman, this would be a competent but generic fantasy. There are swords, horses, inns, a vaguely European feel — familiar elements to any fantasy reader or role player.

Freelorn’s rightful-ruler-in-exile plot is also as old as the hills, although this book only sets it up; that story is reserved for The Door Into Sunset (1993, Tor Books), the third volume.

There’s also a significant ancient ruin, although in this case, it’s not full of treasures but doors.

(The italicization of doors — meaning magical doors through time and space — is the only thing in this book that truly irritates me. I would have almost preferred capitalization, and I’m not a fan of Significant Capital Letters in Fantasy.)

(The italicization of doors — meaning magical doors through time and space — is the only thing in this book that truly irritates me. I would have almost preferred capitalization, and I’m not a fan of Significant Capital Letters in Fantasy.)

I have to admit, there are a few places where the worldbuilding didn’t work for me. For instance, the royal succession is patrilineal, and I’m really not sure that would work in a society built around free love. Matrilineal descent is much easier to keep track of.

Still, this is a relatively small quibble, and it didn’t occur to me the first time I read the book. The writing is solid, and the pace brisk enough to hurry the readers past any such questions.

Add characters, culture, and religion, not to mention the little touches of science that Duane tends to put in her fantasy, and the story becomes unique.

Herewiss and Freelorn are deeply in love with each other, but at the same time it’s not an especially stable relationship. Herewiss lacks faith in Freelorn and tends to let his issues stew; Freelorn has a self-sabotaging side and goes for the low blow when he’s angry.

The other main human character is Segnbora, warrior woman, failed Flame wielder, and — although her story is reserved for the second book — control freak with longstanding issues.

The book also features a fire elemental, Sunspark; from the description, his name means “solar flare” but Herewiss lacks the terminology to express this. As an alien being, Sunspark is a convenient way to voice questions about the world, but it isn’t all exposition. For instance, Sunspark doesn’t understand death or why humans would want to avoid it. He — she? it? — comes to respect human wishes on the matter, but one gets the impression he still thinks of it as a bizarre superstition.

The book also features a fire elemental, Sunspark; from the description, his name means “solar flare” but Herewiss lacks the terminology to express this. As an alien being, Sunspark is a convenient way to voice questions about the world, but it isn’t all exposition. For instance, Sunspark doesn’t understand death or why humans would want to avoid it. He — she? it? — comes to respect human wishes on the matter, but one gets the impression he still thinks of it as a bizarre superstition.

The last major character — shown briefly, but ubiquitous — is the Goddess. All humans in this world encounter the Goddess at least once in their lives. Her love for humans isn’t platonic, either; sex is part of these meetings, at least for those who want it. She walks the world, bargaining and interfering and sometimes engaging in downright cold-blooded manipulation to create heroes — because this is an explicitly imperfect universe.

This is one of those Duane scientific touches. The Goddess’s great error was that she inadvertently built death into her creation, and the narration makes it clear that “death” also means the heat death of the universe.

The Door Into Fire comes off as a mixture of the familiar and the strange. I find it extremely enjoyable.

I should warn potential readers of one thing: this book is part of a series, the Tale of the Five, and although The Door Into Shadow (1983) and The Door Into Sunset (1993) wrap up most of the story, the fourth and final book, The Door into Starlight, hasn’t been published.

That said, I recommend it highly.

Diane Duane’s The Door Into Fire was published in paperback by Dell in 1979 and has been reprinted several times, most recently in eBook format. The sequel, The Door Into Shadow, appeared in 1983 (trade paperback, BlueJay Books), and Meisha Merlin assembled both into an omnibus, Tale of Five: The Sword and the Dragon, in 2004. The third volume, The Door Into Sunset, was published by Tor in March, 1993.

Isabel Pelech is the author of “The Wine-Dark Sea,” from Black Gate 14. Her last review for us was Patricia A. McKillip’s The Sorceress and the Cygnet

The Door Into Fire covert art by Terry Oakes.